Search london history from Roman times to modern day

William The Conqueror AND THE RULE OF THE NORMANS

FRANK MERRY STENTON, M.A. - Late Scholar of Keble College, Oxford

Copyright 1908

SEAL OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

In attempting to write a life of William the Conqueror, one is confronted, at the outset, by a question of considerable urgency. The mere details of the King’s history, if full discussion were given to all matters which have been the subjects of controversy, would far exceed the possible limits of a volume to be included in the series to which the present book belongs. On the other hand, a life of William the Conqueror which ignored the changes in constitutional organisation and social life which followed the events of 1066 would obviously be a very imperfect thing. Accordingly, I have reserved the last three chapters of the book for some examination of these questions; and I hope that the footnotes to the text may serve as, in some sort, a guide to the more difficult problems arising out of the Conqueror’s life and reign.

There is no need to enter here upon a description of the authorities on which the following book is based. For the most part they have been the subjects of thorough discussion; and, with one exception, they are sufficiently accessible in modern editions. The writs and charters issued over England by William I. are only to be found scattered among a great number of independent ivpublications; and the necessity of forming a collection of these documents has materially delayed the appearance of the present work.

It remains that I should here tender my thanks to all those who have rendered assistance to me during the writing of this book. In particular I would express my gratitude to my friend Mr. Roland Berkeley-Calcott, and to the general editor of this series, Mr. H. W. C. Davis. To Mr. Davis I am indebted for invaluable help and advice given to me both during the preparation of the book and in the correction of the proof-sheets. To those modern writers whose works have re-created the history of the eleventh century in England and Normandy I hope that my references may be a sufficient acknowledgment.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| CHAPTER I - HE MINORITY OF DUKE WILLIAM AND ITS RESULTS | 63 |

| CHAPTER II - REBELLION AND INVASION | 96 |

| CHAPTER III - THE CONQUEST OF MAINE AND THE BRETON WAR | 126 |

| CHAPTER IV - THE PROBLEM OF THE ENGLISH SUCCESSION | 143 |

| CHAPTER V - THE PRELIMINARIES OF THE CONQUEST AND THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS | 180 |

| CHAPTER VI - FROM HASTINGS TO YORK | 211 |

| CHAPTER VII - THE DANISH INVASION AND ITS SEQUEL | 267 |

| CHAPTER VIII - THE CENTRAL YEARS OF THE ENGLISH REIGN | 304 |

| CHAPTER IX - THE LAST YEARS OF THE CONQUEROR | 344 |

| CHAPTER X - WILLIAM AND THE CHURCH | 376 |

| CHAPTER XI - ADMINISTRATION | 407 |

| CHAPTER XII - DOMESDAY BOOK | 457 |

| INDEX | 503 |

| JUMIÈGES ABBEY—FAÇADE | 66 | ||

| Reproduced by permission of Levy et ses Fils, Paris. | |||

| JUMIÈGES ABBEY—INTERIOR | 80 | ||

| Reproduced by permission of Levy et ses Fils, Paris. | |||

| THE SIEGE OF DINANT | 140 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| From Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| SEAL OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR | 148 | ||

| From Rymer’s Fœdera (published 1704). | |||

| HAROLD ENTHRONED | 158 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| From Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| HAROLD’S OATH | 162 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| From Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| THE BUILDING OF HASTINGS CASTLE | 188 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| From Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| viiiTHE DEATH OF HAROLD | 198 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| From Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| FOSSE DISASTER, BATTLE OF HASTINGS | 204 | ||

| FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY | |||

| Reproduced from Vetusta Monumenta of the Society of Antiquaries of London (published 1819). | |||

| ST. JOHN’S CHAPEL, IN THE TOWER OF LONDON | 228 | ||

| CHARTER OF WILLIAM I. TO THE LONDONERS | 230 | ||

| IN THE ARCHIVES OF THE CORPORATION | |||

| Facsimile prepared by F. Madan, M. A., Reader in Palæography in the University of Oxford. | |||

| THE BAILE HILL, YORK | 270 | ||

| THE SITE OF WILLIAM I.’S SECOND CASTLE | |||

| Reproduced from Traill’s Social England. | |||

| TOMB OF ROBERT COURTHOSE, THE ELDEST SON OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR, DUKE OF NORMANDY, GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL | 350 | ||

| THE EFFIGY IS OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY | |||

| Reproduced from a photograph by Pitcher, Gloucester, England. | |||

| WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR | 360 | ||

| AS CONCEIVED BY A FRENCH PAINTER OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY | |||

| The original of this picture, now lost, was painted by an artist when the tomb of the Conqueror was opened in 1522. A copy executed in 1708, is preserved in the sacristy of St Etienne’s Church at Caen; the present illustration is from a photograph of that copy. | |||

| ixREDUCED FACSIMILE OF THE CHARTER OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR TO HYDE ABBEY | 382 | ||

| Reproduced from Liber Vitæ of New Minster and Hyde Abbey, Winchester. Edited by W. de Gray Birch. | |||

| GAMEL SON OF ORME’S SUNDIAL | 388 | ||

| From A Short Account of Saint Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale, by Rev. F. W. Powell, Vicar. | |||

| WILLIAM’S WRIT TO COVENTRY | 420 | ||

| From Facsimiles of Royal and Other Charters in the British Museum. Edited by George F. Warner and Henry J. Ellis. | |||

| PLAN OF GREAT CANFIELD CASTLE, ESSEX | 440 | ||

| From Victoria History of the Counties of England. | |||

| AUTOGRAPH SIGNATURES TO WINDSOR AGREEMENT | 448 | ||

| Reproduced from Palæographical Society’s Facsimiles of Manuscripts and Inscriptions. | |||

| A PORTION OF A PAGE OF DOMESDAY BOOK | 458 | ||

| THE BEGINNING OF THE BERKSHIRE SECTION | |||

| Facsimiles prepared by F. Madan, M.A., Reader in Palæography in the University of Oxford. | |||

| A PORTION OF A PAGE OF DOMESDAY BOOK | 466 | ||

| THE BEGINNING OF THE BERKSHIRE SECTION | |||

| Facsimiles prepared by F. Madan, M.A., Reader in Palæography in the University of Oxford. | |||

| COINS | |||

| [1]PENNY OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR | 62 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF GEOFFREY MARTEL | 95 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF HENRY I. OF FRANCE | 125 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF CONAN II. OF BRITTANY | 142 | ||

| [2]PENNY OF HAROLD HARDRADA | 179 | ||

| [1]PENNY OF HAROLD II. | 210 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF BALDWIN OF LILLE | 266 | ||

| [2]PENNY OF SWEGN ESTUTHSON | 303 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF ROBERT LE FRISON | 343 | ||

| [2]DENIER OF PHILIP I. OF FRANCE | 375 | ||

| [3]PENNY OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR | 406406 | ||

| [3]PENNY OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR | 456 | ||

| [3]PENNY OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR | 501 | ||

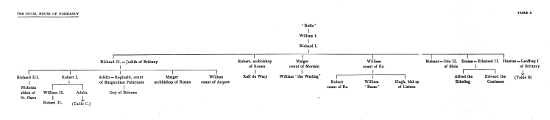

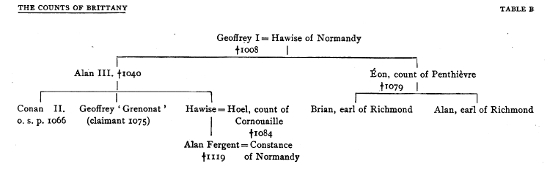

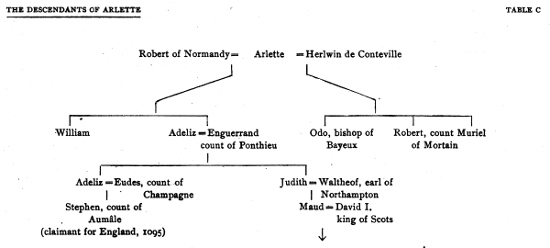

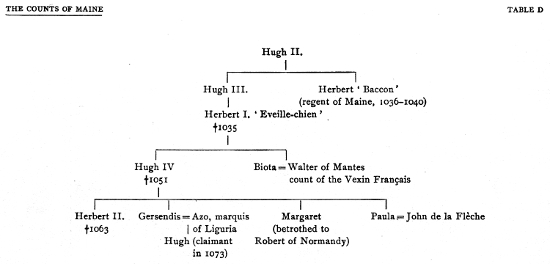

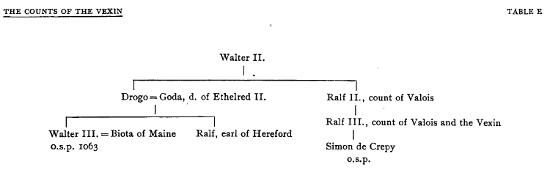

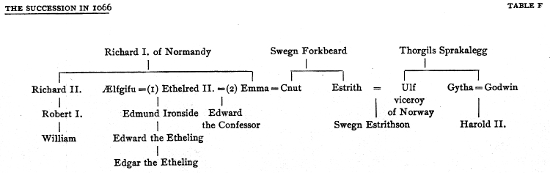

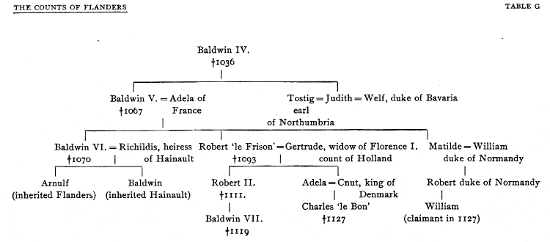

| GENEALOGICAL CHARTS | FACING PAGE 502 | ||

| TABLE A—THE DUCAL HOUSE OF NORMANDY | |||

| TABLE B—THE COUNTS OF BRITTANY | |||

| TABLE C—THE DESCENDANTS OF ARLETTE | |||

| TABLE D—THE COUNTS OF MAINE | |||

| xiTABLE E—THE COUNTS OF THE VEXIN | |||

| TABLE F—THE SUCCESSION IN 1066 | |||

| TABLE G—THE COUNTS OF FLANDERS | |||

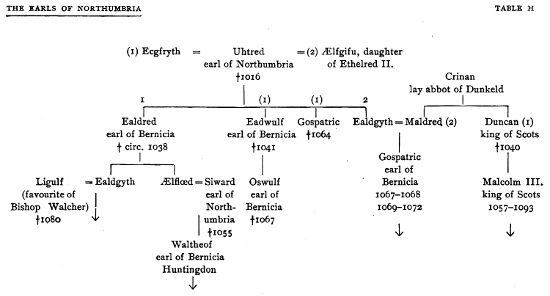

| TABLE H—THE EARLS OF NORTHUMBRIA | |||

| MAPS | |||

| MAP OF EASTERN NORMANDY AND THE BORDER COUNTIES | 64 | ||

| MAP OF YORKSHIRE IN 1066–1087 | 268 | ||

| MAP OF WESTERN NORMANDY | 360 | ||

| MAP OF ENGLAND IN 1087 | 374 | ||

| MAP OF EARLDOMS, MAY, 1068 | 412 | ||

| MAP OF EARLDOMS, JANUARY, 1075 | 414 | ||

| MAP OF EARLDOMS, SEPTEMBER, 1087 | 416 | ||

Table A: The Ducal House of Normandy. [Transcription]

Table A: The Counts of Brittany. [Transcription]

Table C: The Descendants of Arlette. [Transcription]

Table D: The Counts of Maine. [Transcription]

Table E: The Counts of the Vexin. [Transcription]

Table F: The Succession in 1066 [Transcription]

Table G: The Counts of Flanders [Transcription]

Table H: The Earls of Northumbria [Transcript]

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

530

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

1. From the Catalogue of English Coins in the British Museum, Anglo-Saxon Series.

2. From the Traité de Numismatique du Moyen Age, by Arthur Engel and Raymond Serrure.

3. From the Handbook of the Coins of Great Britain and Ireland in British Museum.

4. The boundary of the Danelaw in its full extent is proved by certain twelfth-century lists of shires which divide England into “Westsexenelage,” “Mirchenelage,” and “Danelage.” With regard to earlier times, the territory of the Five Boroughs is delimited by the fiscal peculiarities described below (Chapter XII.), and the kingdom of Northumbria substantially corresponds with Yorkshire as surveyed in Domesday Book, but it is very uncertain how far Guthrum’s kingdom extended westward after his final peace with Alfred. London was annexed to Wessex, but the boundary does not seem to have coincided in any way with the later county divisions.

5. See below, Chapter XII.

6. Chadwick, Studies in Anglo-Saxon Institutions, chapter v.

7. Chadwick, op. cit.

8. Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond, 167.

9. See the account of the council at Bretford, below, page 61.

10. See Plummer, Life and Times of Alfred the Great, 67.

11. “Unready” here represents the A. S. unrædig—“devoid of counsel”—and is applied to Ethelred because of his independence of the advice of the witan.

12. E. H. R., vii., 209.

13. See Eckel, Charles le Simple.

14. This identification cannot be considered certain. See Flodoard, ed. P. Lauer.

15. The main features of Norman society in the eleventh century are described in outline by Pollock and Maitland, History of English Law, i., chapter iii., on which the following sketch is founded.

16. The scanty evidence which exists on this matter is summarised by Pollock and Maitland, H. E. L., chapter iii., and by Haskins, E. H. R., Oct., 1907.

17. See on this matter F. Lot, Fidèles ou Vassaux.

18. See Histoire Général de France, Les Premiers Capetiens, p. 90; also Sœhnée, Catalogue des Actes d’Henri Ier No. 38.

19. See Bohmer’s Kirche und Staat in England und in der Normandie, 20.

20. The fullest account of Cnut’s reign is given by Freeman. Norman Conquest i., chapter vi. Freeman was disposed to underrate the value of Scandinavian evidence, and hence considered Cnut’s reign almost exclusively from the English standpoint.

21. See the lives of Earls Eric and Eglaf in the notes to the Crawford Charters, No. xii.

22. P. and M., i., 20.

23. The most recent discussion in detail of this episode is that of Plummer, Two Saxon Chronicles, ii. Freeman’s attempt to clear Godwine of complicity was marked by a very arbitrary treatment of the contemporary authorities.

24. Heimskringla, trans. Morris and Magnusson, vol. iii., p. 10.

25. Op. cit., p. 181.

26. This is the duty of “hospitium,” exemption from which was frequently granted in Anglo-Norman charters.

27. Swegen, Godwine’s eldest son, went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and died on his way back.

28. See the map of the earldoms in 1066 given by Freeman, Norman Conquest, ii.

29. In the next generation there was a tradition that Gospatric had been murdered by Queen Edith on her brother’s behalf, Florence of Worcester, 1065.

30. Victoria History of Northamptonshire, i., 262–3.

31. In addition to the future Conqueror one other child was born to Robert and Arlette—a daughter named Adeliz, who married Count Enguerrand of Ponthieu; and after Robert’s death Arlette herself became the lawful wife of a Norman knight named Herlwin of Conteville, whose two sons, Odo, bishop of Bayeux, and Robert, count of Mortain, play a considerable part in the succeeding history.

32. Ralf Glaber, iv., 6.

33. De la Borderie, Histoire de Bretagne, iii., 8–12.

34. Round, Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, 526.

35. This grant rests solely on the authority of Ordericus Vitalis, but it is accepted by Flach, Les origines de l’ancienne France, 528–530.

36. The meeting place of this council is only recorded by William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii., 285.

37. Ordericus Vitalis, iii., 431.

38. Among contemporaries who made the journey may be mentioned Count Fulk Nerra of Anjou and Archbishop Ealdred of York.

39. Ordericus, ii., 369. Tutorem sui, Ducis.

40. Gesta Regum, ii., 285.

41. Gesta Regum, ii., 285. “Normannia fiscus regalis erat.” Henry of Huntingdon, 189.

42. This is the opinion of Luchaire, Institutions monarchiques, ii., 17.

43. William of Jumièges, vii., 3.

44. Round, Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 37.

45. Round, Calendar, No. 251.

46. Luchaire, Institutions monarchiques, ii., 233.

47. This is asserted very strongly by Freeman, ii., 201, and is implied by Luchaire, Les Premières Capétiens, 163.

48. The whole story of the duke’s ride from Valognes to Falaise rests upon the sole authority of Wace, and is only given here as a matter of tradition.

49. The topography of the battle is derived from Wace.

50. William of Poitiers, 81.

51. Ordericus Vitalis (iii., 342) makes a pointed reference to the length of time occupied by the present siege in comparison with the capture of Brionne in a single day by Robert of Normandy in 1090. But it is impossible to accept his statement that the resistance of Guy of Burgundy was protracted for three years.

52. William of Poitiers, 81: “Bella domestica apud nos in longum sopivit.”

53. In the imperfectly feudalised state of England a stricter doctrine seems to have prevailed: see, on Waltheof’s case below, page 338.338.

54. This rests on no better authority than Wace. We know with more certainty that the lands which Grimbald forfeited were bestowed by William upon the See of Bayeux, of which Odo, the duke’s brother, became bishop in 1048.—Eng. Hist. Rev., xxii., 644.

55. “Vicissitudinem post hæc ipse Regi fide studiosissima reddidit.”

56. William of Poitiers, 82.

57. William of Poitiers, 82.

58. William of Poitiers, 87.

59. William of Poitiers, 88.

60. William of Jumièges, vii., 18.

61. William of Jumièges, vii., 18. The duke’s oath is given by Wace: Roman de Rou, 9468.

62. William of Poitiers, 89.

63. William of Jumièges, vii., 19.

64. William of Jumièges, vii., 20.

65. The visit of William to England in 1051 will be considered below, Chapter IV., in its bearing upon the general question of the English succession.

66. William of Poitiers, 92.

67. This is definitely asserted by William of Malmesbury.

68. See on this episode, Round, Feudal England, 382–385.

69. Page 95.

70. William of Jumièges, vii., 7.

71. Labbè Concilia, xi., 1412.

72. For example, Freeman, N. C., iii., 92.

73. Count Baldwin III. assumed the title of Marquis on the coins which he issued.

74. Vita Eadwardi (R.S.), 404.

75. Page 97. On this question there is a conflict of evidence William of Jumièges, whose authority is only second to that of William of Poitiers, definitely asserts Geoffrey’s participation in the campaign. See Halphen, Conté d’Anjou, 77. On the other hand, although the argument from the silence of William of Poitiers should not be pressed too far, the terms of the treaty of 1053 (see below) certainly suggest that the king held Geoffrey guilty of a breach of feudal duty, and later writers, such as Orderic, cannot be trusted implicitly in regard to the detailed history of this period.

76. William of Poitiers, 99.

78. William of Jumièges, vii., 25.

79. See The Laws of Breteuil, by Miss M. Bateson, Eng. Hist. Rev., xx.

80. William of Poitiers, 99, 100.

81. In a charter abstracted by Round, Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 1256, there is a reference to a knight named Richard who was seized by mortal illness while defending the frontier post of Châteauneuf-en-Thimerais in this campaign.

82. William of Poitiers, 101. Wace gives topographical details.

83. William of Jumièges, vii., 28. The battle of Varaville led to the king’s retreat, but a sporadic war lasted till 1060. It is probable that Norman chroniclers have attached more importance to the battle than it really possessed.

84. See Halphen, Comté d’Anjou, p. 133.

85. The history of Maine at this period has recently been discussed by Flach, Les origines de l’ancienne France, vol. iii., p. 543–9.

86. The native Mancel authorities have little to say about the war of 1063, the course of which is described by William of Poitiers, 103 et seq.

88. Round. Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 937.

89. Rhiwallon was brother of Junquené, the archbishop of Dol, whose presence at the Norman court during William’s minority has been noted above. De la Borderie, iii., p. [missing].

90. William of Poitiers (109–112) is the sole authority for this war and he gives no dates. He definitely asserts the presence of Harold and his companions in the Norman army, and his narrative contains nothing irreconcilable with the relevant scenes in the Bayeux tapestry. The war was probably intended to enforce Norman suzerainty over Brittany, and the rising of Rhiwallon of Dol probably gave William his opportunity. De la Borderie, Histoire de Bretagne, iii., p. [missing].

91. The canons of Chartres celebrated his obit on December 11th, a fact which discounts the story in William of Jumièges that Conan was poisoned by an adherent of William. If William had wished to remove Conan the latter would certainly have died before William had sailed for England.

92. The scheme of policy which Green (Conquest of England, 522–524, ed. 1883) founded in relation to their marriage rests upon this assumption.

93. Poem in Worcester Chronicle, 1057.

94. Vita Eadwardi Confessoris (R. S.), 410.

95. Worcester Chronicle, 1042: “All the people chose Edward and received him for King, as it belonged to him by right of birth.”

96. Chadwick, Studies in Anglo-Saxon Institutions, Excursus iv., p. 355.

97. The one contemporary account of Harold’s oath which we possess is that given by William of Poitiers (ed. Giles, 108). According to this Harold swore (1) to be William’s representative (vicarius) at Edward’s court; (2) to work for William’s acceptance as king upon Edward’s death; (3) in the meantime to cause Dover castle to receive a Norman garrison, and to build other castles where the duke might command in his interest. In a later passage William of Poitiers asserts that the duke wished to marry Harold to one of his daughters. In all this there is nothing impossible, and to assume with Freeman that the reception of a Norman garrison into a castle entrusted to Harold’s charge would have been an act of treason is to read much later political ideas into a transaction of the eleventh century. William was Edward’s kinsman and we have no reason to suppose that the king would have regarded with disfavour an act which would have given his cousin the means of making good the claim to his succession which there is every reason to believe that he himself had sanctioned twelve years before.

98. Vita Edwardi Confessoris (R. S.), 432.

99. William of Poitiers, 123.

100. William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii., 299.

101. The statement that William promised, if successful, to hold England as a fief of the papacy is made by no writer earlier than Wace, who has no authority on a point of this kind.

102. Monumenta Gregoriana.

103. Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, 8.

104. William of Poitiers, 124.

105. William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum.

106. The list followed here is that printed by Giles as an appendix to the Brevis Relatio. Scriptores, p. 21.

107. Guy of Amiens, 34: “Appulus et Caluber, Siculus quibus jacula fervet.”

108. Kingsley, Hereward the Wake, ed. 1889, p. 368.

109. This was Freeman’s final view. N. C., iii., 625.

110. Florence of Worcester, 1066.

111. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 120.

112. Chronicles of Abingdon, Peterborough, and Worcester, 1066.

113. John of Oxenedes, a thirteenth-century monk of St. Benet of Holme, asserts that Harold entrusted the defence of the coast to Ælfwold, abbot of that house. The choice of an East Anglian abbot suggests that his appointment was intended as a precaution against the Scandinavian danger.

114. See Introduction, above, page 48.

115. Heimskringla, page 165.

116. Simeon of Durham, 1066.

117. This episode forms the last entry in the Abingdon version of the Chronicle, and it is described in a northern dialect.

118. Round, Calendar of Documents preserved in France, No. 1713.

119. William of Poitiers, 122.

120. W. P., 123. “Turmas militum cernens, non exhorrescens.”

121. Guy of Amiens, ed. Giles, 58.

122. William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii., 300.

123. William of Poitiers, 125.

124. William of Poitiers, 126.

125. Abingdon Chronicle, 1066.

126. Guy of Amiens: “Diruta quae fuerant dudum castella reformas; Ponis custodes ut tueantur ea.”

127. W. P.: “Normanni previa munitione Penevesellum, altera Hastingas occupavere.”

128. See on this point Round, Feudal England, 150–152.

129. William of Poitiers, 128.

130. William’s real numbers probably lay between six and seven thousand.

131. See the paraphrase of this passage in the Roman de Rou, Freeman, N. C., iii., 417.

132. Guy of Amiens, p. 31: “Ex Anglis unus, latitans sub rupe marina Cemit ut effusas innumeras acies. Scandere currit equum; festinat dicere regi.”

133. Gaimar, l’Estoire des Engles, R. S., i., p. 222. Gaimar wrote in the twelfth century, but he followed a lost copy of the A.-S. chronicle.

134. For the chronology of the campaigns of Stamfordbridge and Hastings the dates given by Freeman are followed here.

135. Worcester Chronicle, 1066: “He com him togenes at thœre haran apuldran.”

136. The statement that Harold further strengthened his position by building a palisade in front of it rests solely on an obscure and probably corrupt passage in the Roman de Rou (lines 7815 et seqq). Apart altogether from the textual difficulty, the assertion of Wace is of no authority in view of the silence both of contemporary writers and of those of the next generation. In regard to none of the many earlier English fights of this century have we any hint that the position of the army was strengthened in this manner; nor in practice would it have been easy for Harold to collect sufficient timber to protect a front of 800 yards on the barren down where he made his stand. The negative evidence of the Bayeux tapestry is of particular importance here; for its designer could represent defences of the kind suggested when he so desired, as in the case of the fight at Dinan.

137. Spatz, p. 30, will only allow to William a total force of six to seven thousand men.

138. W. P., 133. “Cuncti pedites consistere densius conglobati.” For the arrangement of the English army on the hill see Baring, E. H. R., xx., 65.

139. It is probable that the expressions in certain later authorities (e.g. W. M., ii., 302, “pedites omnes cum bipennibus conserta ante se testudine”) from which the formation by the English of a definite shield or wall has been inferred mean no more than this. The “bord weal” of earlier Anglo-Saxon warfare may also be explained as a poetical phrase for a line of troops in close order.

See Round, Feudal England, 360–366.

140. This fact, which must condition any account to be given of the battle of Hastings, was first stated by Dr. W. Spatz, “Die Schlacht von Hastings,” section v., “Taktik beider Heere,” p. 34.

141. This point is brought out strongly by Oman, History of the Art of War.

142. Spatz, p. 29, uses this fact to limit the numbers of the Norman army.

143. W. P., 132.

144. Guy of Amiens: “Lævam Galli, dextram petiere Britanni. Dux cum Normannis dimicat in medio.”

145. W. P., 132.

146. Florence of Worcester, 1066: “Ab hora tamen diei tertia usque ad noctis crepusculum.”

147. Guy of Amiens. W. P., 133: “Cedit fere cuncta Ducis acies.”

148. “Fugientibus occurrit et obstitit, verberans aut minans hasta.”—W. P., 134.

149. Bayeux tapestry scene: “Hic Odo episcopus, baculum tenens, confortat pueros.”

150. W. P., 134.

151. “Animadvertentes Normanni ... non absque nimio sui incommodo hostem tantum simul resistentem superari posse.”—W. P., 135.

152. “Normanni repente regirati equis interceptos et inclusos undique mactaverunt.”—W. P., 135.

153. “Bis eo dolo simili eventu usi.”—William of Poitiers, 135.

154. “Languent Angli, et quasi reatum ipso defectu confitentes, vindictum patiuntur.”—W. P., 135.

155. Baring, E. H. R., xxii., 71.

156. “Jam inclinato die.”—W. P., 137. Crepusculi tempore.—Florence of Worcester, 1066.

157. Baring, E. H. R., xxii., 69.

158. Guy of Amiens.

159. See the Waltham tract, De Inventione Sancti Crucis, ed. Stubbs. William of Malmesbury was evidently acquainted with this legend.

160. It is probable that Wulfnoth had been taken together with Harold by Guy of Ponthieu, and had been left behind in Normandy as a surety for the observance of his brother’s oath to William.

161. Gesta Regum, R. S., 307.

162. Thomas Stubbs, ed. Raine; Historians of the Church of York, R. S., ii., 100.

163. William of Poitiers, 139.

164. William of Poitiers, 139.

165. Guy of Amiens, 607.

166. William of Poitiers, 140.

167. Guy of Amiens, 617.

168. The embassy to Winchester is only mentioned by Guy of Amiens, who omits all reference to William’s illness, which is derived from William of Poitiers. Guy, however, places the message at this point of the campaign.

169. Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, 4.

170. This is clearly meant by the statement of William of Poitiers that William’s troops burned “quicquid ædificiorum citra flumen invenere.”

171. William of Poitiers, 141.

172. The Worcester Chronicle, followed by Florence of Worcester, 1066, asserts that Edwin and Morcar submitted at “Beorcham,” but William of Poitiers, whose authority is preferable on a point of this kind, implies that they did not give in their allegiance until after the coronation. On the geography relating to these events see Baring, E.H.R. xiii., 17.

173. William of Poitiers, 142.

174. Guy of Amiens, 687 et seqq.

175. William of Poitiers, 143.

176. “Vehementer trementem,” Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 157.

177. Florence of Worcester, 1066.

178. William of Poitiers, 147–8.

179. This writ was issued in favour of one Regenbald, who had been King Edward’s chancellor. It was printed by Round in Feudal England, 422, with remarks on its historical importance.

180. Monasticon, i., 383. See also Round, Commune of London, 29.

181. Monasticon, i., 301. The date assigned here to these documents, of which the text in the Monasticon edition is very faulty, is a matter of inference; but the personal names which occur in them suggest that they should be assigned to the very beginning of William’s reign.

182. Round, Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 1423. See also Commune of London, 30.

183. William of Poitiers, 148; Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 165.

184. Peterborough Chronicle, 1066. “And menn guldon him gyld ... and sithan heora land bohtan.”—D. B., ii., 360. “Hanc Terram habet abbas ... quando redimebant Anglici terras suas.” The combination of these statements led Freeman to make the suggestion referred to in the text.

185. It may be noted that there exist a few proved cases in which a Norman baron had married the daughter of his English predecessor, so that here the king’s grant to the stranger would only confirm the latter in possession of his wife’s inheritance.

186. D. B., i., 285 b. (Normanton on Trent).

187. Victoria History of Northamptonshire, i., 324.

188. Frequently printed, e.g., by Stubbs, Select Charters, 82.

189. Suggested by Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, 439.

190. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 167. The mercenaries were paid off at Pevensey before William sailed for Normandy.

191. Peterborough Chronicle, 1087.

192. William of Poitiers (149) states that William Fitz Osbern was left in charge of the city “Guenta,” which is described as being situated fourteen miles from the sea which divides the English from the Danes, and as a point where a Danish army might be likely to land. These indications imply that Norwich (Venta Icenorum) was Fitz Osbern’s headquarters, although the name Guenta alone would naturally refer to Winchester (Venta Belgarum). The joint regency of Odo and William is asserted by Florence of Worcester, 1067, and the phrase in William of Poitiers, that Fitz Osbern “toto regno Aquilionem versus præesset,” suggests that the Thames was the boundary between his province and that of Odo. The priority of Fitz Osbern in the regency is suggested by the fact that in a writ relating to land in Somerset, he joins his name with that of the king in addressing the magnates of the shire. Somersetshire certainly formed no part of his direct sphere of administration at the time. For further references to this writ see below, Chapter XI.

193. The fullest list of names is given by Orderic, ii., 167.

194. William of Poitiers, 155.

195. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 170.

196. Simeon of Durham, under the year 1072. He asserts that Oswulf himself slew Copsige in the door of the church.

197. Simeon of Durham, under 1070.

198. Florence of Worcester, 1067.

199. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 173.

200. The fullest account of the affair at Dover is given by Orderic (ii., 172–5), who expands the slighter narrative of William of Poitiers.

201. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 178.

202. Ordericus Vitalis., ii., 179.

203. “Ad Danos, vel alio, unde auxilium aliquod speratur, legatos missitant.”—William of Poitiers, 157.

204. The story of the revolt of Exeter is critically discussed by Round, Feudal England, 431–455.

205. Worcester Chronicle, 1067; Florence of Worcester, 1068; William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, ii., 312.

206. The source of our information is an original charter granted by William to the church of St. Martin’s le Grand on May 11th.—E. H. R. xii., 109.

207. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 183.

208. The rising of Edwin and Morcar is not mentioned by the English authorities, which are only concerned with the movements of Edgar and his companions. Florence of Worcester says that the latter fled the court through the fear of imprisonment. They had given no known cause of offence since their original submission, but it is probable that they would have been kept in close restraint if they had been in the king’s power when the northern revolt broke out and that they fled to avoid this.

209. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 184.

210. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 185.

211. Simeon of Durham, 1069.

212. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 188. From his statement that Earl William beat the rebels “in a certain valley,” it is evident that the military operations were not confined to the city of York.

213. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 189.

214. For the events of 1069 Orderic is almost the sole authority, and his narrative is not always easy to follow. On the other hand he is doubtless in great part following the contemporary William of Poitiers, and his tale is quite consistent with itself if due allowance is made for its geographical confusion.

215. The exact scene of Waltheof’s exploit is uncertain. Orderic implies that the entire Norman garrison in York perished in the unsuccessful sally. Florence of Worcester states that the castles were taken by storm. The latter is certainly the more probable, and agrees better with the tradition, preserved by William of Malmesbury, of the slaughter at the gate. The gate in question, on this reading of the story, will belong to one of the castles; it cannot well be taken to be one of the gates of the town.

216. The mutilation is only recorded by a late authority, the Winchester Annals.

217. Ordericus’ narrative at this point is not very clear, but this is probably his meaning.

218. By Ordericus William is made to return to York through Hexham (“Hangustaldam revertabatur a Tesca”). This being impossible it is generally assumed that Helmsley (Hamilac in D. B.) should be read for Hexham, in which case William would probably cross the Cleveland hills by way of Bilsdale.

219. “Desertores, vero, velut inertes, pavidosque et invalidos, si discedant, parvi pendit.”

220. Chester castle was planted within arrow shot of the landing stage on the right bank of the Dee, and also commanded the bridge which carried the road from the Cheshire plain to the North Wales coast.

221. Peterborough Chronicle, 1069.

222. William of Malmesbury, Gesta Pontificum, § 420.

223. Domesday Book, i., 346.

224. Peterborough Chronicle, 1070.

225. The passages which follow are founded on the narrative of Hugh “Candidus,” a monk of Peterborough, who in the reign of Henry II. wrote an account of the possessions of the abbey, and inserts a long passage descriptive of the events of 1070. The beginning of his narrative agrees closely with the contemporary account in the Peterborough Chronicle, but his tale of the doings of the Danes in Ely after the sack of Peterborough is independent, and bears every mark of truth. Wherever it is possible to test Hugh’s work, in regard to other matters, its accuracy is confirmed. See Feudal England, 163, V.C.H. Notts, i., 222. Hugh’s Chronicle has not been printed since its edition by Sparke in the seventeenth century.

226. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 216. The death of Edwin formed the conclusion of the narrative of William of Poitiers as Orderic possessed it.

227. Florence of Worcester, 1070.

228. Historia Eliensis, 240.

229. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 216.

230. Florence of Worcester, 1071.

231. Historia Eliensis, 245.

232. See “Ely and her Despoilers,” in Feudal England, 459.

233. Gaimar, L’estoire des Engles, R. S.

234. Gesta Herewardi, R. S.

235. See Varenbergh, Relations Diplomatiques entre le comté de Flandre et l’Angleterre. Luchaire, Les Premiers Capetiens, 169.

236. Halphen, Comté d’Anjou, 180, has shown that Azo had appeared in Maine by the spring of 1069.

237. The authorities for the present war are the history of Ordericus Vitalis and the life of Bishop Arnold of Le Mans, ed. Mabillon; Vetera Analecta.

238. “Facta conspiratione quam communionem vocabant.”—Vet. An., 215.

239. Gesta Regum, ii., 316.

240. Vetera Analecta, 286.

241. Hoel, unlike his predecessors, followed a policy of friendship towards Anjou, and restored to Fulk le Rechin the conquests made by Count Conan on the Angevin march. De la Borderie, iii., 26.

242. The terms of the peace of Blanchelande are given by Orderic.

243. E. H. R., xx., 61.

244. See table H.

245. Simeon of Durham, 1072.

246. This third flight of Edgar to Scotland rests solely upon the authority of Simeon of Durham, and it is quite possible that the latter may have been confused about the course of events at this point.

247. Worcester Chronicle, 1073.

248. Brian’s tenure of the earldom of Richmond is proved by a charter to the priory of St. Martin de Lamballe, in which lands are granted by “Brientius, comes Anglica terra.” (De la Borderie, iii., 25.) As Brian’s father, Count Éon of Penthievre, did not die before 1079 the title “comes” cannot refer to any French county possessed by Brian. As in the eleventh century every “earldom” consisted of a shire or group of shires, it would seem to follow that Richmondshire at this date was regarded as a territorial unit distinct from Yorkshire.

249. Norman Conquest, iv., 517.

250. Worcester Chronicle, 1075.

251. Worcester Chronicle, 1075.

252. According to Wace Ralf had served among the Breton auxiliaries at the battle of Hastings.

253. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 258 et seq.

254. Florence of Worcester, 1074.

255. Worcester Chronicle, 1076.

256. Epistolæ Lanfranci.

257. Florence of Worcester, 1074.

258. It does not appear that any medieval historian regarded this as an act of treachery on Waltheof’s part.

259. F. N. C., iv., 585.

260. Gesta Regum, ii., 312.

261. This point is made by Pollock and Maitland. H. E. L., i., 291.

262. For the rest of the Conqueror’s reign, there was peace between Normandy and Brittany, except that in 1086 William, to whom the new count Alan Fergant, the son of Hoel, had refused homage, crossed the border once more and laid siege to Dol. In this siege also he was unsuccessful, and speedily came to terms with Alan, who received Constance, the Conqueror’s daughter, in marriage.

263. Simeon of Durham, 1075.

264. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 290.

265. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 259.

266. Charter of King Philip to St. Quentin, Gallia Christ; X. Inst. 247. Among the witnesses are Anselm of Bec, and Ives de Beaumont, the father-in-law of Hugh de Grentemaisnil.

267. Worcester Chronicle, 1079.

268. S. D., Gesta Regum, 1080.

269. Round, Calendar, No. 1114.

270. Ibid., 1113.

271. Ibid., 78.

272. Orderic, ii., 315.

273. This fact is of importance, as giving an example, rare in England, of a true “vicecomes,” an earl’s deputy as distinguished from a sheriff.

274. For all these events Simeon of Durham is the authority giving most detail.

275. Hist. Monast. de Abingdon, ii., 10.

276. Brut y Tywysogion, 1080.

277. Mon. Angl., vii., 993, from an “inspeximus” of 31 Ed. I. The charter in question is dated “apud villam Dontonam,” which in the index to the volume of Patent Rolls is identified with Downton, Wilts. William, at Downton, may very well have been on his way to one of the Hampshire or Dorset ports.

278. iii., 168. On the other hand, Giesbrecht (iii., 531) has suggested that a political difference was the occasion of the quarrel between Odo and William, the former wishing to take up arms for Gregory VII., while the latter was on friendly terms with the emperor. But Gregory himself in a letter addressed to William (Register, viii., 60), while reproving his correspondent for lack of respect towards his brother’s orders, admits that Odo had committed some political offence against the king. As to the nature of that offence, we have no contemporary statement, nor do we know how far Gregory may have possessed accurate information as to the motives which induced William’s action.

279. William of Malmesbury.

280. Ordericus Vitalis, iii., 196.

281. An isolated reference to the siege of Saint-Suzanne occurs in the Domesday of Oxfordshire, in which county the manor of Ledhall had been granted to Robert d’Oilly, “apud obsidionem S. Suzanne.”

282. Heimskringla, iii., 198.

283. The severity of the devastation should not be exaggerated, for in 1086 Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk were the most prosperous parts of England.

284. Cnut’s preparations and death are described at length in his life by Ethelnoth, printed in the Scriptores Rerum Danicarum.

285. Peterborough Chronicle, 1086.

286. See Flach, Les Origines de l’ancienne France, 531–534.

287. The ecclesiastical history of Normandy and England in the eleventh century is treated by Böhmer, Kirche und Staat in England, und in der Normandie, on which book this chapter is based.

289. Especially in the Danelaw, V. C. H., Derby i., Leicester i.

290. Stubbs, Select Charters, 85. The writ in question probably belongs to the year 1075.

291. Pollock and Maitland, i., 89.

292. Peterborough Chronicle, 1083.

293. Abbot Ethelhelm of Abingdon was considered to have offended in this respect. Hist. Monast. de Abingdon, ii., 283.

294. See above, Chapter V.

295. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 315.

296. Easter, 1069: King William; Matilda, the Queen; Richard, the King’s son; Stigand, archbishop of Canterbury; Ealdred, archbishop of York; William, bishop of London; Ethelric, bishop of Selsey; Herman, bishop of Thetford; Giso, bishop of Wells; Leofric, bishop of Exeter; Odo, bishop of Bayeux; Geoffrey, bishop of Coutances; Baldwin, bishop of Evreux; Arnold, bishop of Le Mans; Count Robert (of Mortain), Earl William Fitz Osbern, Count Robert of Eu, Earl Ralf (of Norfolk?), Brian of Penthievre, Fulk de Alnou, Henry de Ferrers; Hugh de Montfort, Richard the son of Count Gilbert, Roger d’ Ivri, Hamon the Steward, Robert, Hamon’s brother.—Tardif, Archives de l’Empire, 179.

Christmas, 1077: King William; Lanfranc, archbishop of Canterbury; Thomas, archbishop of York; Odo, bishop of Bayeux; Hugh, bishop of London; Walkelin, bishop of Winchester; Remi, bishop of Lincoln; Maurice, the chancellor; Vitalis, abbot of Westminster; Scotland, abbot of Ch. Ch., Canterbury; Baldwin, abbot of St. Edmunds; Simeon, abbot of Ely; Aelfwine, abbot of Ramsey; Serlo, abbot of Gloucester; Earl Roger of Montgomery, Earl Hugh of Chester, Count Robert of Mortain, Count Alan of Richmond, Earl Aubrey of Northumbria, Hugh de Montfort, Henry de Ferrers, Walter Giffard, Robert d’ Oilli, Hamon the Steward, Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester.—Ramsey Chartulary, R. S., ii., 91.

Easter, 1080: King William; Matilda the Queen; Robert, the king’s son; William, the king’s son; William, archbishop of Rouen; Richard, archbishop of Bourges; Warmund, archbishop of Vienne; Geoffrey, bishop of Coutances; Gilbert, bishop of Lisieux; Count Robert, the king’s brother; Count Roger of Eu, Count Guy of Ponthieu, Roger de Beaumont, Robert and Henry, his sons, Roger de Montgomery, Walter Giffard, William d’ Arques.—Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, ed. J. H. Round, No. 78.

297. Printed in Transactions of Somerset Archæological and Historical Society, xxiii., 56

298. Bath Chartulary (Somerset Record Society), i., 36.

299. Hist. Monasterii de Abingdon, R. S., ii., 9.

300. Ibid., 10.

301. Round, Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 712.

302. Henry I. is seldom found north of Nottingham.

303. Monasticon, iii., 377.

304. V. C. H., Warwick, i., 258.

305. See above, Chapter VI.

306. See the complaints of his aggressions in Heming’s History of the Church of Worcester; Monasticon, i., 593–599.

307. William of Malmesbury, ii., 314.

308. Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, No. 77.

309. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 178.

310. Compare Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, 322.

311. See the charters of William II. in Monasticon, viii., 1167.

312. Ordericus Vitalis, ii., 219.

313. Reproduced herewith.

314. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, i., 339.

315. Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond, 80-83.

316. Charter of William I., Monasticon, i., 477.

317. Foundation charter of Blyth Priory, Monasticon, iv., 623.

318. There is some evidence to suggest that the lord of a vill could cause a court to be held there by his steward. This, however, is the result of seignorial, not communal, ideas.

319. Round, Feudal England, 225–314, has given the clearest account of the introduction and development of knight service in England.

320. Feudal England, as quoted above, page 447. See also Morris, Welsh Wars of Edward, i., 36, arguing for a total of 5000.

321. Frequently printed, e.g. by Stubbs, Select Charters, 86.

322. Birch, Cartularium, i., 414.

323. Birch, Cartularium, iii., 671; Maitland, Domesday Book, 502.

324. Birch, Cartularium, iii., 671; Maitland, Domesday Book, 456.

325. Maitland, D. B. and Beyond, 4.

326. The fact that the assessment of southern and western England was based upon a conventional unit of five hides was first enunciated by Mr. J. H. Round in Feudal England.

327. Vinogradoff, E. H. R., xix., 282.

328. Feudal England, 98–103.

329. For the “six-carucate unit” see Feudal England, 69. Victoria Histories, Derby, Notts, Leicester, and Lincoln.

330. Feudal England, 42.

331. V. C. H., Derby, i., 295.

332. This was the view of Professor Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond, 24.

333. The contemporary description of the Domesday Survey published by Stevenson, E. H. R., xxii., 72, makes it probable that the bordars were in theory distinguished from other classes by the fact that they possessed no share in the arable fields of the vill.

334. See V. C. H., Hertford, i., 293.

335. V. C. H., Bedford, i., 200.

336. The former view is that of Mr. Round, the latter that of Professor Maitland.

337. We also know that the returns were checked in each county by a second set of commissioners who were deliberately sent by the king into shires where they possessed no personal interest.—E. H. R., xxii., 72.

338. Feudal England, 141.

339. Dialogus de Saccario (ed. 1902), p. 108.

A series of biographical studies of the lives and work of a number of representative historical characters about whom have gathered the great traditions of the Nations to which they belonged, and who have been accepted, in many instances, as types of the several National ideals. With the life of each typical character will be presented a picture of the National conditions surrounding him during his career.

The narratives are the work of writers who are recognized authorities on their several subjects, and, while thoroughly trustworthy as history, will present picturesque and dramatic “stories” of the Men and of the events connected with them.

To the Life of each “Hero” will be given one duodecimo volume, handsomely printed in large type, provided with maps and adequately illustrated according to the special requirements of the several subjects.

| Nos. 1–32, each | $1.50 |

| Half Leather | 1.75 |

| No. 33 and following Nos., each | (By mail, $1.50, net 1.35) |

| Half Leather (by mail, $1.75) | net 1.60 |

In the story form the current of each National life is distinctly indicated, and its picturesque and noteworthy periods and episodes are presented for the reader in their philosophical relation to each other as well as to universal history.

It is the plan of the writers of the different volumes to enter into the real life of the peoples, and to bring them before the reader as they actually lived, labored, and struggled—as they studied and wrote, and as they amused themselves. In carrying out this plan, the myths, with which the history of all lands begins, will not be overlooked, though these will be carefully distinguished from the actual history, so far as the labors of the accepted historical authorities have resulted in definite conclusions.

The subjects of the different volumes have been planned to cover connecting and, as far as possible, consecutive epochs or periods, so that the set when completed will present in a comprehensive narrative the chief events in the great Story of the Nations; but it is, of course, not always practicable to issue the several volumes in their chronological order.

| 12o Illustrated, cloth, each | $1.50 |

| Half leather, each | 1.75 |

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content