Search london history from Roman times to modern day

Between the first Angevin war and the outbreak of overt hostilities between Normandy and France, there occurs a period of five or six years the historical interest of which lies almost entirely in the internal affairs of the Norman state. It was by no means an unimportant time; it included one external event of great importance, William’s visit to England in 1051, but its real significance lay in the gradual consolidation of his power in Normandy and its results. On the one hand it was in these years that William finally suppressed the irreconcilable members of his own family; on the other hand the gradual dissolution of the traditional alliance between Normandy and the Capetian house runs parallel to this process and is essentially caused by it. From the very time when William attained his majority these two powers begin steadily to drift apart; the breach widens as William’s power increases, and the support given by the king of France in these years to Norman rebels such as William Busac and William of Arques is naturally followed by his invasions of Normandy in 1054 and 1058. As compensation for this William’s 97marriage with Matilda of Flanders falls within the same period, and events ruled that the alliance thus formed was to neutralise the enmity of the Capetian house at the critical moment of the invasion of England. There is indeed a sense in which we may say that it was William’s success in these six years which made the invasion of England possible; whether consciously or not, William was making indispensable preparation for his supreme endeavour when he was taking the castles of his unquiet kinsmen and banishing them from Normandy.

The first of them to go was William surnamed “the Warling,” count of Mortain and grandson of Duke Richard the Fearless. His fall was sudden and dramatic. As we have only one narrative of these events it may be given here at length:

“At that time William named the Warling, of Richard the Great’s line, was count of Mortain. One day a certain knight of his household, called Robert Bigot, came to him and said, ‘My Lord, I am very poor and in this country I cannot obtain relief; I will therefore go to Auplia, where I may live more honourably.’ ‘Who,’ said William, ‘has advised you thus?’ ‘The poverty which I suffer,’ replied Robert. Then said William, ‘Within eight days, in Normandy itself, you shall be able in safety to seize with your own hands whatever you may require.’ Robert therefore, submitting to his lord’s counsel, bided his time, and shortly afterwards, through Richard of Avranches his kinsman, gained the acquaintance of the duke. One day they were talking in private when Robert 98among other matters repeated the above speech of Count William. The duke thereupon summoned the count and asked him what he meant by talk of this kind, but he could not deny the matter, nor did he dare to tell his real meaning. Then said the duke in his wrath: ‘You have planned to confound Normandy with seditious war, and wickedly have you plotted to rebel against me and disinherit me, therefore it is that you have promised booty to your needy knight. But, God granting it, the unbroken peace which we desire shall remain to us. Do you therefore depart from Normandy, nor ever return hither so long as I live.’ William thus exiled sought Apulia wretchedly, accompanied by only one squire, and the duke at once promoted Robert his brother and gave him the county of Mortain. Thus harshly did he abuse the haughty kindred of his father and honourably exalt the humble kindred of his mother.”[63]

The moral of the story lies in its last sentence. The haughty kindred of the duke’s father were beginning to show themselves dangerous, and William threw down the challenge to them once for all when he disinherited the grandson of Richard the Great in favour of the grandson of the tanner of Falaise. But, apart from the personal questions involved, the tale is eminently illustrative of William’s conception of his duty as a ruler. By policy as well as prepossession he was driven to be the stern maintainer of order; the men who would stir up civil war in Normandy 99wished also to disinherit its duke, and from this followed naturally that community of interest between the ruler and his meaner subjects as against the greater baronage which was typical of the early Middle Ages in Normandy and England alike. It is inadvisable to scrutinise too narrowly the means taken by William to secure his position; if on the present occasion he exiled his cousin on the mere information of a single knight, he had already been taught the wisdom of striking at the root of a rebellion before it had time to grow to a head. We must not expect too much forbearance from the head of a feudal state in his dealings with a suspected noble when the banishment of the latter would place a dangerous fief at the former’s disposal. Lastly, we may notice the way in which Apulia is evidently regarded as a land of promise at this time by all who seek better fortune than Normandy can give them. In the eleventh century, as in the fifteenth, Italy was exercising its perennial attraction for the men of the ruder north, and under the leadership of the sons of Tancred of Hauteville a new Normandy was rising on the wreck of the Byzantine Empire in the West by the shores of the Ionian Sea.

Probably about this time, and possibly not without some connection with the disaffection of William the Warling, there occurred another abortive revolt, of which the scene was laid, as usual, in one of the semi-independent counties 100held by members of the ducal house. In the north-east corner of Normandy the town of Eu with its surrounding territory had been given by Duke Richard II. to his illegitimate brother William. The latter had three sons, of whom Robert, the eldest, succeeded him in the county, Hugh, the youngest, subsequently becoming bishop of Lisieux. The remaining brother, William, surnamed Busac, is a mysterious person whose appearance in history is almost confined to the single narrative which we possess of his revolt. The latter is not free from difficulty; William was not his father’s eldest son, and yet at the period in question he appears in possession of the castle of Eu, and, which is much more remarkable, he is represented as laying claim to the duchy of Normandy itself. At present this is inexplicable, but it is certain that the duke besieged and took Eu and drove William Busac into exile. The place of refuge which he chose is very suggestive. He went to France and attached himself to King Henry, who married him to the heiress of the county of Soissons, where his descendants were ruling at the close of the century.[64] It is plain that the king’s opportunist policy has definitely turned against William of Normandy, when we find a Norman rebel received with open arms and given an important territorial position on the border of the royal demesne.[65]

101The third and last of this series of revolts can be definitely assigned to the year 1053. It arose like the revolt of William Busac in the land east of Seine, and its leader was again one of the “Ricardenses,” a member of a collateral branch of the ducal house. William count of Arques was an illegitimate son of Duke Richard II., and therefore brother by the half blood to Duke Robert I., and uncle to William of Normandy. With the object of conciliating an important member of his family the latter had enfeoffed his uncle in the county of Arques, the district between Eu and the Pays de Caux. Before long, however, relations between the duke and the count became strained; William of Arques was said to have failed in his feudal duty at the siege of Domfront, and when a little later he proceeded to fortify the capital of his county with a castle, it was known that his designs were not consonant with loyalty towards the interests of his lord and nephew. In the hope of anticipating further trouble the duke insisted on his legal right of garrisoning the castle with his own troops, but the precaution proved to be quite futile, for the count soon won over the garrison, defied his nephew, and spread destruction over as wide an area as he could reach from his base of operations. At this time, as at the similar crisis of 1047, William seems to have been at Valognes; he was certainly somewhere in the Cotentin 102when the news of what was happening at Arques was brought to him.[66] Without a moment’s delay he rode off towards the scene of the revolt, crossing the Dive estuary at the ford of St. Clement and so past Bayeux, Caen, and Pont Audemer to the Seine at Caudebec, and then to Baons-le-Comte and Arques, his companions dropping off one by one in the course of his headlong ride until only six were left. Near to Arques, however, he fell in with a party of three hundred horsemen from Rouen, who had set out with the object of preventing the men of Arques from carrying supplies into the castle. William had not yet outgrown the impetuosity which called forth King Henry’s admonitions in the campaign of 1048: he insisted on delivering an instant attack, believing that the rebels would shrink from meeting him in person, and dashed on to the castle regardless of the remonstrances of the Rouen men, who counselled discretion. Charging up the castle mound he drove the count and his men within the fortress as he had anticipated, and we are given to understand that but for their hastily shutting the gates against him the revolt would have been ended then and there.

The surprise assault having failed, nothing was left but a blockade, and accordingly William established a counterwork at the base of the castle and entrusted it to Walter Giffard, lord of the neighbouring estate of Longueville, while he himself 103went off, “being called by other business,” as his panegyrist tells us. As a matter of fact it is probable that he withdrew from a sense of feudal propriety,[67] for no less a person than King Henry of France was advancing to the relief of the garrison. On all grounds it was desirable for William to refrain from setting a bad example to his barons by actually appearing in arms against his own overlord, and so the operations against the king were left to the direction of others. At the outset they were fortunate. There were still a few barons in the county of Arques who had not joined the rebels, and one of them, Richard of Hugleville, possessed a castle, a few miles from Arques itself, at St. Aubin, which lay on the line of march of the French king. Possibly it was this fact which suggested to the besiegers the idea of intercepting the king before he reached Arques; at any rate, they formed a plan of the kind, which proved successful and curiously anticipates one of the most famous episodes in the greater battle of Hastings. The king, who had been marching carelessly with a convoy of provisions intended for the garrison within Arques, halted near to St. Aubin. In the meantime the Normans before Arques had sent out a detachment which they divided into two parts, the greater part secreting itself not far from St. Aubin, while the rest made a feint attack on the royal army. After a short conflict the latter division turned in 104pretended flight, drew out a number of the king’s army in pursuit, and enticed them past the place where the trap was laid, whereupon the hidden Normans sallied out, fell on the Frenchmen, and annihilated them, slaying Enguerrand, count of Ponthieu, and many other men of note. Notwithstanding this check, the king hurried on to Arques, and succeeded in throwing provisions into the castle, and then, eager to avenge the disaster at St. Aubin, he made a savage attack on the counterwork at the foot of the hill. But its defences were strong and its defenders resolute: so the king, to avoid further loss, beat a hasty retreat to St. Denis, and with his withdrawal Duke William reappeared upon the scene.[68] Then the blockade was resumed in earnest, and we are told that its severity convinced the count of Arques of his folly in claiming the duchy against his lord. Repeated messages to King Henry begging for relief found him unwilling to risk any further loss of prestige, and at last hunger did its work. The garrison surrendered, asking that life and limb might be guaranteed to them, but making no further stipulation, and William of Poitiers gleefully describes the ignominious manner of their exit from the castle.[69] Here, as after Val-es-dunes, it was not the duke’s policy, if it lay in his power, to proceed to extremities against the beaten rebels, and William was notably lenient 105to his uncle, who was deprived of his county and his too-powerful castle, but was granted at the same time a large estate in Normandy. However, like Guy of Burgundy, he declined to live in the country over which he had hoped to rule and he went into voluntary exile at the court of Eustace of Boulogne.

One outlying portion of the duchy remained in revolt after the fall of Arques. On the south-western border of Normandy the fortress of Moulins had been betrayed to the king by Wimund, its commander, and had received a royal garrison under Guy-Geoffrey, brother of the duke of Aquitaine. The importance of this event lay in the fact that Moulins in unfriendly hands threatened to cut off communications between the Hiesmois and the half-independent county of Bellême. Fortunately for the integrity of the duchy, the fate of Moulins was determined by the surrender of Arques; the garrison gave up their cause as hopeless, and retired without attempting to stand a siege.[70]

At some indefinite point in the short interval of peace which followed the revolt of William of Arques, William of Normandy was married to Matilda, daughter of Baldwin count of Flanders, in the minster at Eu. On William’s part the consummation of the marriage was an act of simple lawlessness noteworthy in so faithful a son of Holy Church, for in 1049 the General 106Council of Rheims had solemnly forbidden Count Baldwin to give his daughter to William of Normandy, and had simultaneously inhibited William from receiving her.[71] A mystery which has not been wholly solved hangs over the motives which underlay this prohibition; for genealogical research has hitherto failed to discover any tie of affinity which might furnish an impediment, reasonable or otherwise, to the proposed marriage, while at the middle of the eleventh century the provisions of the canon law on the subject of the prohibited degrees were much less rigid and fantastic than they subsequently became. Yet the decree is duly entered among the canons of the Council of Rheims, and it served to keep William and his chosen bride apart for four years. Early in 1053, however, Pope Leo IX. had been taken prisoner by the Normans in Italy at the battle of Aversa, and the coincidence of his captivity with William’s defiance of the papal censure has not escaped the notice of historians.[72] By all churchmen of the stricter sort a marriage celebrated under such conditions was certain to be regarded as a scandal. Normandy was laid under an interdict, and in the duchy itself the opposition was headed by two men of very different character. Malger, the archbishop of Rouen at the time, was a brother of the fallen count of Arques, and the excommunication which 107he pronounced against his erring nephews was probably occasioned as much by the political grievances of his family as by righteous indignation at the despite done to the Council of Rheims. William speedily came to an understanding with the Pope by means of which he was enabled to remove Malger from his archbishopric, but the marriage was also condemned by the man who both before and after that event held above all others the place of the duke’s familiar friend. The career of Lanfranc of Pavia, at this moment prior of Bec, will be more fittingly considered elsewhere, but his opposition to William’s marriage was especially significant because of his great legal knowledge and the disinterestedness of his motives, and the uncompromising attitude of his most intimate counsellor cut the duke to the quick. In the outburst of his anger William savagely ordered that the lands of the monastery of Bec should be harried, and that Lanfranc himself should instantly depart from Normandy. A chance meeting between the duke and the prior led to a reconciliation, and Lanfranc was thereupon employed to negotiate with the papal court for a recognition of the validity of the marriage. Nevertheless five years passed before Pope Nicholas II. in 1059 granted the necessary dispensation, accompanied by an injunction that William and his wife should each build and endow a monastery by way of penance for their disobedience; and the reasons for this long delay are 108almost as difficult to understand as are the grounds for the original prohibition in 1049. But it is probable that William, having once taken the law into his own hands and gained possession of his bride, was well content that the progress of his suit at Rome should drag its slow length along, trusting that time and the chances of diplomatic expediency might soften the rigours of the canon law, and bring the papal curia to acquiescence in the accomplished fact.

The county of Flanders, with which Normandy at this time became intimately connected, held a unique position among the feudal states of the north. Part only of the wide territory ruled by Baldwin IV. owed feudal service to the king of France, for the eastern portion of the county was an imperial fief, and the fact of his divided allegiance enabled the count of Flanders to play the part of an international power. By contemporary writers Count Baldwin is occasionally graced with the higher title of Marquis,[73] and the designation well befitted the man who ruled the wealthiest portion of the borderland between the French kingdom and the German empire. The constant jealousy of his two overlords secured him in practical independence, and in material resources it is probable that no prince between the English Channel and the Alps could compete with the lord of Bruges and Ghent; for the great cities 109of Flanders were already developing the wealth and commercial influence which in the next generation were to give them the lead in the movement for communal independence. For some thirty years we find Baldwin cultivating the friendship of England, as became a ruler whose subjects were already finding their markets in English ports; and as the political situation unfolded itself, the part he chose to take in the strife of parties across the Channel became a matter of increasing concern for English statesmen. “Baldwin’s land,” as the English chronicler terms it, was the customary resort of political exiles from England, and in 1066 it was the attitude of the count of Flanders which, as we shall see, really turned the scale in favour of William of Normandy. At the early date with which we are dealing no one could have foreseen that this would be so, but the value of a Flemish alliance was already recognised in England by the aggressive house with which William was at last to come into deadly conflict. In 1051, Tosig, son of Earl Godwine of Wessex, wedded Judith, Count Baldwin’s sister,[74] and this fact inevitably gave a political complexion to William’s marriage to Matilda, two years later. Godwine, as leader of the English nationalists, and William as ultimate supporter of the Normans in England, were each interested to secure the alliance of a power which might intervene with decisive effect on either side and could not be 110expected to preserve strict neutrality in the event of war. William was too shrewd a statesman to ignore these facts; yet after all he probably regarded his marriage rather as the gratification of a personal desire than as a diplomatic victory.

Long before the political results of William’s marriage had matured themselves, the relations between the duke of Normandy and the king of France had entered upon a new phase. The event of the war of 1053 had shewn that it was eminently in the interests of the French monarchy that the growth of the Norman power should be checked before it could proceed to actual encroachment on the royal demesne; and also that if this were to be accomplished it would no longer suffice for King Henry to content himself with giving support to casual Norman factions in arms against their lawful ruler. This plan had led to ignominious failure, and it was clear that in future it would be necessary for King Henry to appear as a principal in the war and test whether the Norman duke was strong enough to withstand the direct attack of his suzerain. These considerations produced a phenomenon rarely seen at this date, for the king proceeded to collect an army in which, through the rhetoric in which our one contemporary writer veils its composition, we must recognise nothing less than the entire feudal levy of all France. So rarely does French feudalism combine to place its military resources at the disposal of its sovereign that the fact on this 111occasion is good evidence of the current opinion as to the strength of Normandy under its masterful duke. In the war which followed, the territorial principles which found their fullest expression in the policy of the dukes of Normandy gained a signal victory over incoherent feudalism represented by the king of France at the head of the gathered forces of his heterogeneous vassals. Not until successive kings had reduced the royal demesne to such unity as had already been reached by Normandy in the eleventh century, could the French crown attempt successful aggressive war.

In addition to their feudal duty, certain of the king’s associates in the forthcoming campaign had their individual reasons for joining in an attack on Normandy. The ducal house of Aquitaine would naturally be attracted into the quarrel by the failure of Guy-Geoffrey to hold Moulins in the late war; Guy of Ponthieu had to avenge his brother’s death at St. Aubin. Little as the several feudal princes of France may have loved their suzerain, their jealousy would readily be roused by the exceptional power of one of their own number, and the king seems to have found little difficulty in collecting forces from every corner of his realm. From the Midi the counts of Poitou and Auvergne and the half-autonomous dukes of Aquitaine and Gascony sent contingents; north of the Loire, every state from Brittany to the duchy of Burgundy was represented in the royal army with one singular exception. Whatever 112the reason of his absence, Geoffrey Martel, William’s most formidable rival, does not appear in the list of the king’s associates as given by William of Poitiers.[75] This may be due to a mere oversight on the latter’s part, or more probably it may be that Geoffrey was too independent to take part in an expedition which, although directed against his personal enemy, was commanded by his feudal lord. But with or without his aid the army which obeyed the king’s summons was to all seeming overwhelmingly superior to any force which the duke of Normandy could put into the field.

With so great an army at his disposal, the king could well afford to divide his forces and make a simultaneous invasion of Normandy at two different points. The lower course of the Seine supplied a natural line of demarcation between the spheres of operation of the two invading armies, and accordingly the royal host mustered in two divisions, one assembling in the Beauvoisis to ravage the Pays de Caux, the other assembling at Mantes, and directed at the territory of 113Evreux, Rouen, and Lisieux. The first division was drawn from those lands between the Rhine and the Seine, which owed allegiance to the French crown, and was placed under the command of Odo the king’s brother and Reginald of Clermont. The army which gathered at Mantes comprised the Aquitanian contingent, together with troops drawn from the loyal provinces north of Loire and west of Seine, and was led by the king in person. The general plan of campaign is thus intelligible enough, but its ultimate purpose is not so clear, perhaps because the king himself had formed no plans other than those which related to the actual conduct of the war. On his part William formed a scheme of defence corresponding to his enemies’ plan of attack. He took the field in person with the men of the Bessin, Cotentin, Avranchin, Auge, and Hiesmois, the districts, that is, which were threatened by the king and his southern army, entrusting the defence of the Pays de Caux to leaders chosen on account of their local influence, Count Robert of Eu, Hugh of Gournai, Hugh de Montfort, Walter Giffard, and Gilbert Crispin, the last a great landowner in the Vexin. William’s object was to play a purely defensive game, a decision which was wise as it threw upon the king and his brother the task of provisioning and keeping together their unwieldly armies in hostile territory. The invading force moved across the country, laying it waste after the ordinary fashion of feudal 114warfare, William hanging on the flank and rear of the king’s army, cutting off stragglers and foraging parties and anticipating the inevitable devastation of the land by removing all provisions from the king’s line of advance. The king had penetrated as far as the county of Brionne when disaster fell on the allied army across the Seine. Thinking that William was retiring in front of the king’s march the leaders of the eastern host ignored the local force opposed to themselves in the belief, we are told, that all the knights of Normandy were accompanying the duke. But the count of Eu and his fellow-officers were deliberately reserving their blow until the whole of their army had drawn together, and the French met little opposition until they had come to the town of Mortemer, which they occupied and used as their headquarters while they ravaged the neighbourhood in detail at their leisure. Spending the day in plunder they kept bad watch at night, and this fact induced the Norman leaders to try the effect of a surprise. Finding out the disposition of the French force through spies, they moved up to Mortemer by night and surrounded it before daybreak, posting guards so as to command all the exits from the town; and the first intimation which the invaders received of their danger was the firing of the place over their heads by the Normans. Then followed a scene of wild confusion. In the dim light of the wintry dawn the panic-struck Frenchmen instinctively made for 115the roads which led out of the town, only to be driven in again by the Normans stationed at these points. Some of course escaped; Odo the king’s brother and Reginald of Clermont got clear early in the day, but for some hours the mass of the French army was steadily being compressed into the middle of the burning town. The Frenchmen must have made a brave defence, but they had no chance and perished wholesale, with the exception of such men of high rank as were worth reserving for their ransoms. Among these last was Count Guy of Ponthieu, whose brother Waleran perished in the struggle, and who was himself kept for two years as a prisoner at Bayeux before he bought his liberty by acknowledging himself to be William’s “man.” The victory was unqualified, and William knew how to turn it to fullest account.

He received the news on the night following the battle, and instantly formed a plan, which, even when described by his contemporary biographer, reads like a romance. As soon as he knew the result of the conflict he summoned one of his men and instructed him to go to the French camp and bring to the king himself the news of his defeat. The man fulfilled his directions, went off, climbed a high tree close to the king’s tent, and with a mighty voice proclaimed the event of the battle. The king, awakened by these tidings of disaster from the air, was struck with terror, and, without waiting for the dawn, broke 116up his camp, and made with what haste he might for the Norman border. William, seeing that his main purpose was in a fair way of achievement, refrained from harassing the king’s disorderly retreat; the French were anxious to end so unlucky a campaign, and peace was soon made. According to the treaty the prisoners taken at Mortemer were to be released on payment of their ransoms, while the king promised to confirm William in the possession of whatever conquests he had made, or should thereafter make, from the territory of Geoffrey of Anjou.[76] Herein, no doubt King Henry in part was constrained by necessity, but in view of his defeat it was not inappropriate that he should make peace for himself at the expense of the one great vassal who had neglected to obey the summons to his army.[77] And it should be noted that William, though he has the French king at so great a disadvantage, nevertheless regards the latter’s consent to his territorial acquisitions as an object worth stipulation; King Henry, to whatever straits he might be reduced, was still his overlord, and could alone give legal sanction to the conquests made by his vassals within the borders of his kingdom.

It would, however, be a mistake to regard this treaty as marking a return to the state of affairs which prevailed in 1048, when the king and the duke of Normandy were united against the count of Anjou in the war which ended with the capture 117of Alençon. The peace of 1054 was little more than a suspension of hostilities, each party mistrusting the other. The first care of the duke, now that his hands were free, was to strengthen his position against his overlord, and one of the border fortresses erected at this time was accidentally to become a name of note in the municipal history of England. Over against Tillières, the border post which King Henry had taken from Normandy in the stormy times of William’s minority, the duke now founded the castle of Breteuil, and entrusted it to William fitz Osbern, his companion in the war of Domfront.[78] Under the protection of the castle, by a process which was extremely common in French history, a group of merchants came to found a trading community or bourg. The burgesses of Breteuil, however, received special privileges from William fitz Osbern and when he, their lord, became earl of Hereford these privileges were extended to not a few of the rising towns along the Welsh border. The “laws of Breteuil,” which are mentioned by name in Domesday Book, and were regarded as a model municipal constitution for two centuries after the conquest of England, thus take their origin from the rights of the burgesses who clustered round William’s border fortress on the Iton.[79]

Another castle built at this time was definitely 118intended to mark the reopening of hostilities against the count of Anjou. At Ambrières, near the confluence of the Mayenne and the Varenne, William selected a position of great natural strength for the site of a castle which should command one of the chief lines of entry from Normandy into the county of Maine. The significance of this will be seen in the next chapter, and for the present we need only remark that in 1051, on the death of Count Hugh IV., Geoffrey Martel, by a brilliant coup d’état had secured his recognition by the Manceaux as their immediate lord, and was therefore at the present moment the direct ruler of the whole county. On the other hand, the widow of the late count had sought refuge at William’s court, and her son Herbert, the last male of the old line of the counts of Maine, had commended himself and his territory to the Norman duke. For three years, therefore, William had possessed a good legal pretext for interference in the internal affairs of Maine; and but for the unquiet state of Normandy during this time, followed by the recent French invasion, it is probable that he would long ago have challenged his rival’s possession of the territory which lay between them. That the foundation of the castle of Ambrières was regarded as something more than a mere casual acquisition on William’s part, is shewn by the action of Geoffrey of Mayenne, one of the chief barons of the county of Maine, on hearing the news of its intended fortification. With the 119punctiliousness which distinguishes all William’s dealings with Geoffrey Martel, William had sent word to the count of Anjou that within forty days he would enter the county of Maine and take possession of Ambrières. Geoffrey of Mayenne, whose fief lay along the river Mayenne between Ambrières and Anjou, thereupon went to his lord and explained to him that if Ambrières once became a Norman fortress his own lands would never be safe from invasion. He received a reassuring answer; nevertheless, on the appointed day, William invaded Maine and set to work on the castle according to his declaration; and, although rumour had it that Geoffrey Martel would shortly meet him, the days passed without any sign of his appearance. In the meantime, however, the Norman supplies began to run short, so that William thought it the safest plan to dismiss the force which he had in the field, and to content himself with garrisoning and provisioning Ambrières, leaving orders that his men should hold themselves in readiness to reassemble immediately on receiving notice from him. Geoffrey Martel, who had probably been counting on some action of the kind, at once seized his opportunity, and, as soon as he heard that the Norman army had broken up, he marched on Ambrières, having as ally his stepson William, duke of Aquitaine, and Éon, count of Penthievre, the uncle of the reigning duke of Brittany. With William still in the neighbourhood and likely to return at 120any moment, it was no time for a leisurely investment, so Geoffrey made great play with his siege engines, and came near to taking the place by storm. His attack failed, however, and William, drawing his army together again, as had been arranged, compelled the count to beat a hasty retreat. Shortly afterwards Geoffrey of Mayenne was taken prisoner; and William, with a view to further enterprises in Maine, seeing the advantage of placing a powerful feudatory of that county in a position of technical dependence upon himself, kept him in Normandy until he consented to do homage to his captor.[80] It is also probable that on this occasion William still further strengthened his position with regard to Maine by founding on the Sarthon the castle of Roche-Mabille, which castle was entrusted to Roger of Montgomery, and derives its name from Mabel, the heiress of the county of Bellême, and the wife of the castellan.

Three years of quiet followed these events, about which, as is customary with regard to such seasons, our authorities have little to relate to us. In 1058 came the third and last invasion of Normandy by King Henry of France, with whom was associated once more Count Geoffrey of Anjou. No definite provocation seems to have been given by William for the attack, but in the interests of the French crown it was needful now as it had been in 1053 to strike a blow at this over-mighty vassal, and the king was anxious to take his 121revenge for the ignominious defeat he had sustained in the former year. Less formidable in appearance than the huge army which had obeyed the king’s summons in the former year, the invading force of 1058 was so far successful that it penetrated into the very heart of the duchy, while, on the other hand, the disaster which closed the war was something much more dramatic in its circumstances and crushing in its results than the daybreak surprise of Mortemer. This expedition is also distinguished from its forerunner by the fact that the king does not seem to have aimed at the conquest or partition of Normandy: the invasion of 1058 was little more than a plunder raid on a large scale, intended to teach the independent Normans that in spite of his previous failures their suzerain was still a person to be feared. The king’s plan was to enter Normandy through the Hiesmois; to cross the Bessin as far as the estuary of the Dive and to return after ravaging Auge and the district of Lisieux. Now, as five years previously, William chose to stand on the defensive; he put his castles into a state of siege and retired to watch the king’s proceedings from Falaise. It was evidently no part of the king’s purpose to attempt the detailed reduction of all the scattered fortresses belonging to, or held on behalf of, the duke[81]; and this being the case it was best for 122William to bide his time, knowing that if he could possess his soul in patience while the king laid waste his land, the trouble would eventually pass away of its own accord. And so King Henry worked his will on the unlucky lands of the Hiesmois and the Bessin as far as the river Seule, at which point he turned, crossed the Olne at Caen, and prepared to return to France by way of Varaville and Lisieux. William in the meantime was following in the track of the invading army. The small body of men by which he must have been accompanied proves that he had no thought of coming to any general engagement at the time, but suddenly the possibilities of the situation seem to have occurred to him, and he hastily summoned the peasantry of the neighbourhood to come in to him armed as they were. With the makeshift force thus provided he pressed on down the valley of the Bavent after the king, who seems to have been quite unaware of his proximity, and came out at Varaville at the very moment when the French army was fully occupied with the passage of the Dive. The king had crossed the river with his vanguard[82]; his rearguard and baggage train had yet to follow. Seizing the opportunity, which he had probably anticipated, William flung himself upon the portion of the royal army which was 123still on his side of the river and at once threw it into confusion. The Frenchmen who had already passed the ford and were climbing up the high ground of Bastebourg to the right of the river, seeing the plight of their comrades, turned and sought to recross; but the causeway across the river mouth was old and unsafe and the tide was beginning to turn. Soon the passage of the river became impossible, the battle became a mere slaughter, and the Norman poet of the next century describes for us the old king standing on the hill above the Dive and quivering with impotent passion as he watched his troops being cut to pieces by the rustic soldiery of his former ward. The struggle cannot have taken long; the rush of the incoming tide made swimming fatal, and the destruction of the rearguard was complete. With but half an army left to him it was hopeless for the king to attempt to avenge the annihilation of the other half; he had no course but to retrace his steps and make the best terms he could with his victorious vassal. These terms were very simple—William merely demanded the surrender of Tillières, the long-disputed key of the Arve valley.[83] With its recovery, the tale of the border fortresses of Normandy was complete; the duchy had amply vindicated its right to independence, and was now prepared for aggression.

Thus by the end of 1058 King Henry had been 124definitely baffled in all his successive schemes for the reduction of Normandy. With our knowledge of the event, our sympathies are naturally and not unfairly on the side of Duke William, but they should not blind us to the courage and persistency with which the king continued to face the problems of his difficult situation. In every way, of course, the weakest of the early Capetians suffers by comparison with the greatest of all the dukes of Normandy. The almost ludicrous disproportion between the king’s legal position and his territorial power, his halting, inconsistent policy, and the ease with which his best-laid plans were turned to his discomfiture by a vassal who studiously refrained from meeting him in battle, all make us inclined to agree with William’s panegyrical biographer as he contemptuously dismisses his overlord from the field of Varaville. And yet the wonder is that the king should have maintained the struggle for so long with the wretched resources at his disposal. With a demesne far less in area than Normandy alone, surrounded by the possessions of aggressive feudatories and itself studded with the castles of a restive nobility, the monarchy depended for existence on the mutual jealousy of the great lords of France and on such vague, though not of necessity unreal, respect as they were prepared to show to the successor of Charlemagne. The Norman wars of 125Henry I. illustrated once for all the impotence of the monarchy under such conditions, and the kings who followed him bowed to the limitations imposed by their position. Philip I. and Louis VI. were each in general content that the monarchy should act merely as a single unit among the territorial powers into which the feudal world of France was divided, satisfied if they could reduce their own demesne to reasonable obedience and maintain a certain measure of diplomatic influence outside. Accordingly from this point a change begins to come over the relations between Normandy and France; neither side aims at the subjugation of the other, but each watches for such advantages as chance or the shifting feudal combinations of the time may present. Within a decade from the battle of Varaville the duke of Normandy had become master of Maine and England, but in these great events the French crown plays no part.

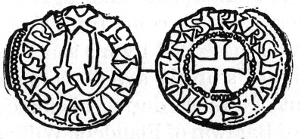

Denier of Henry I. of France

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content