Search london history from Roman times to modern day

By a curious synchronism both King Henry of France and Count Geoffrey Martel died in the course of the year 1060; and, with the disappearance of his two chief enemies of the older generation, the way was clear for William to attempt a more independent course of action than he had hitherto essayed. Up to this year his policy had in great measure been governed by the movements of his overlord and the count of Anjou, both of them men who were playing their part in the political affairs of France at the time when he himself was born. From this date he becomes the definite master of his own fortunes, and the circumstances in which the king and the count left their respective territories removed any check to his enterprise and aggression which might otherwise have come from those quarters. The king was succeeded by his son Philip, at this time a child of scarcely seven years old, and the government of France during his minority was in the hands of Baldwin of Flanders, William’s father-in-law. In Anjou a war of succession broke out which reduced that state to impotence for ten years. Geoffrey Martel had left no sons, but had 127designated as his successor another Geoffrey, nicknamed “le Barbu,” the elder son of his sister Hermengarde by Geoffrey count of the Gatinais.[84] The younger son, however, Fulk “le Rechin,” had determined to secure the Angevin inheritance for himself, and by the time that he had accomplished his purpose most of the territorial acquisitions of Geoffrey Martel had been torn from Anjou by the neighbouring powers. Saintonge and the Gatinais fell respectively into the possession of the duke of Aquitaine and the king of France; and, more important than all, the Angevin acquisition of Maine, the greatest work of Geoffrey Martel, was reversed when in 1063 William of Normandy entered Le Mans and made arrangements for the permanent annexation of the country.

The counts of Maine had never enjoyed such absolute sovereignty over their territory as was possessed by the greater feudatories of the French crown.[85] In addition to the usual vague claims which both Normandy and Anjou were always ready to assert over their weaker neighbours, and which nobody would take seriously when there was no immediate prospect of their enforcement, the suzerainty of the king of France was much more of a reality over Maine than over Flanders or Aquitaine. In particular the patronage of the 128great see of Le Mans rested with the king for the first half of the eleventh century; and this was an important point, for the bishops of the period are prominent in the general history of the county. For the most part they are good examples of the feudal type of prelate, represented in Norman history by Odo of Bayeux and Geoffrey of Coutances; and several of them were drawn from a house fertile in feudal politicians, that of the counts of Bellême, whose great fief lay on the border between Maine and Normandy. This connection of the episcopate of Le Mans with a great Norman family might be taken as itself implying some extension of Norman influence over Maine were it not that the house of Bellême, half independent and altogether unruly, was quite as likely to work against its overlord as in his favour. In fact, it was largely through the Bellême bishops of Le Mans that Angevin power came to be established in Maine for a while; the bishops were steadily opposed to the line of native counts, and looked to Anjou for a counterpoise. In particular, Bishop Gervase (1036–1058) brought it about that King Henry made a grant of all the royal rights over the see to Count Geoffrey Martel for the term of his life, the bishop taking this step in pursuance of an intrigue against the guardian of the reigning count, who was at the time a minor. Having served his turn Gervase quickly fell into disfavour with Geoffrey and endured a seven years’ imprisonment at his hands; but 129it was through his false step that Geoffrey first secured a definite legal position in Mancel politics.

The counts of Maine themselves are rather shadowy people, but it is necessary to get a clear idea of their mutual relationships. Count Herbert, surnamed “Eveille Chien,” the persistent enemy of Fulk Nerra of Anjou and the last of his line to play a part of his own in French affairs, had died in 1035, leaving a son, Hugh IV., and a daughter, Biota, married to Walter of Mantes, count of the Vexin Français. Hugh, being under age, was placed under the governance of his father’s uncle, Herbert “Bacco,” the regent with whom Bishop Gervase was at enmity. When the above-mentioned grant of the patronage of the bishopric of Le Mans to Geoffrey Martel had given the latter a decent pretext for interference in the quarrel, the expulsion of Herbert Bacco quickly followed; and while the bishop was in captivity Geoffrey ruled the country in the name of the young count. Upon his death, in 1051, Geoffrey himself, in despite of the claims of Hugh’s own children, was accepted by the Manceaux as count of Maine—for it should be noted in passing that the Mancel baronage was always attached to Anjou rather than to Normandy. The date at which these events happened is also worthy of remark, for it shows that during that rather obscure war in the Mayenne valley which was describeddescribed in the last chapter William of Normandy was really fighting against Geoffrey Martel in his 130position as count of Maine. A legal foundation for Norman interference lay in the fact, which we have already noticed, that Bertha of Blois, the widow of Hugh III., had escaped into Normandy, and that by her advice her son Herbert, the heir of Maine, had placed himself and his inheritance under the protection of his host. William, seeing his advantage, was determined to secure his own position in the matter. He made an arrangement with his guest by which the latter’s sister Margaret was betrothed to his own son Robert, who here makes his first appearance in history, with the stipulation that if Hugh were to die without children his claims over Maine should pass to his sister and her husband. We do not know the exact date at which this compact was made, but it is by no means improbable that some agreement of the kind underlay that clause in the treaty concluded with King Henry after Mortemer by which William was to be secured in all the conquests which he might make from Geoffrey of Anjou.

On the latter’s death in 1060 Norman influence rapidly gained the upper hand in Maine.[86] The war of succession in Anjou prevented either of the claimants from succeeding to the position of Geoffrey Martel in Maine; and if Count Herbert ruled there at all during the two years which elapsed between 1060 and his own death, in 1062, 131it must have been under Norman suzerainty. With his death the male line of the counts of Maine became extinct, and there instantly arose the question whether the county should pass to Walter, count of Mantes, in right of his wife Biota, the aunt of the dead Herbert, or to William of Normandy in trust for Margaret, Herbert’s sister, and her destined husband, Robert, William’s son. In the struggle which followed, two parties are clearly to be distinguished: one—and judging from events the least influential—in favour of the Norman succession, the other, composed of the nationalists of Maine, supporting the claims of Biota and Walter. The latter was in every way an excellent leader for the party which desired the independence of the county. As count of the Vexin Français, Walter had been steadily opposed to the Norman suzerainty over that district, which resulted from the grant made by Henry I. to Robert of Normandy in 1032. His policy had been to withdraw his county from the Norman group of vassal states, and to reunite it to the royal demesne; he acknowledged the direct superiority of the king of France over the Vexin, and he must have co-operated in the great invasion of Normandy in 1053; for it was at his capital that the western division of the royal host assembled before its march down the Seine valley. Even across the Channel the interests of his house clashed with those of William. Walter was himself the nephew of Edward the Confessor, and 132his brother Ralph who died in 1057 had been earl of Hereford. The royal descent of the Vexin house interfered seriously with any claim which William might put forward to the inheritance of Edward the Confessor on the ground of consanguinity. It is only by placing together a number of scattered hints that we discover the extent of the opposition to William which is represented by Walter of Mantes and his house, but there can be no doubt of its reality and importance.

In Maine itself the leaders of the anti-Norman party seem to have been William’s own “man” Geoffrey of Mayenne and the Viscount Herbert, lord of Sainte-Suzanne. There is no doubt that the mass of the baronage and peasantry of the county were on their side, and this fact led William to form a plan of operations which singularly anticipates the greater campaign of the autumn of 1066. William’s ultimate objective was the city of Le Mans, the capital of Maine and its strongest fortress, the possession of which would be an evident sanction of his claims over the county. But there were weighty reasons why he should not proceed to a direct attack on the city. Claiming the county, as he did, in virtue of legal right, it was not good policy for him to take steps which, even if successful, would give his acquisition the unequivocal appearance of a conquest; nor from a military point of view was it advisable for him to advance into the heart of the county with the castles of its hostile baronage unreduced behind him. 133He accordingly proceeded to the reduction of the county in detail, knowing that the surrender of the capital would be inevitable when the whole country around was in his hands. The initial difficulties of the task were great, and the speed with which William wore down the resistance of a land bristling with fortified posts proves by how much his generalship was in advance of the leisurely, aimless strategy of his times. We know few particulars of the war, but it is clear that William described a great circle round the doomed city of Le Mans, taking castles, garrisoning them where necessary with his own troops, and drawing a belt of ravaged land closer and closer round the central stronghold of the county. By these deliberate measures the defenders of Le Mans were demoralised to such an extent that William’s appearance before their walls led to an immediate surrender. From the historical point of view, however, the chief interest of these operations lies in the curiously close parallel which they present to the events which followed the battle of Hastings. In England, as in Maine, it was William’s policy to gain possession of the chief town of the country by intimidation rather than by assault, and with the differences which followed from the special conditions of English warfare his methods were similar in both cases. London submitted peaceably when William had placed a zone of devastation between the city and the only quarters from which help could come to her; Le Mans could not hope to 134resist when the subject territory had been wasted by William’s army, and its castles surrendered into his hands. Nor can we doubt that the success of this plan in the valleys of the Sarthe and Mayenne was a chief reason why it was adopted in the valley of the Thames.

At Le Mans, as afterwards at London, William, when submission had become necessary, was received with every appearance of joy by the citizens; here, as in his later conquest, he distrusted the temper of his new subjects, and made it his first concern to secure their fidelity by the erection of a strong fortress in their midst—the castle which William planted on the verge of the precincts of the cathedral of Le Mans is the Mancel equivalent of the Tower of London. And, as afterwards in England, events showed that the obedience of the whole country would not of necessity follow from the submission of its chief town; it cost William a separate expedition before the castle of Mayenne surrendered. But the parallel between the Norman acquisition of Maine and of England should not be pressed too far; it lies rather in the circumstances of the respective conquests than in their ultimate results. William was fighting less definitely for his own hand in Maine than afterwards in England; nominally, at least, he was bound to respect the rights of the young Countess Margaret, and her projected marriage with Robert of Normandy proves that Maine was to be treated as an appanage rather than placed under 135William’s immediate rule. And to this must be added that the conquest of Maine was far less permanent and thorough than the conquest of England. The Angevin tendencies of the Mancel baronage told after all in the long run. Before twelve years were past William was compelled to compromise with the claims of the house of Anjou, and after his death Maine rapidly gravitated towards the rival power on the Loire.

While the body of the Norman army was thus employed in the reduction of Maine, William despatched a force to make a diversion by ravaging Mantes and Chaumont, the hereditary demesne of his rival,—an expedition in its way also anticipating the invasion which William was to lead thither in person in 1087, and in which he was to meet his death. Most probably it was this invasion, of which the details are entirely unknown, which persuaded Walter of Mantes to acquiesce in the fait accompli in Maine; at least we are told that “of his own will he agreed to the surrender [of Le Mans], fearing that while defending what he had acquired by wrong he might lose what belonged to him by inheritance.” Within a short time both he and his wife came to a sudden and mysterious end, and there was a suspicion afloat that William himself was not unconcerned in it. It was one of the many slanders thrown upon William by Waltheof and his boon companions at the treasonable wedding feast at Exning in 1075 that the duke had invited his rival and his wife to 136Falaise and that while they were his guests he poisoned them both in one night. Medieval credulity in a matter of this kind was unbounded; and a sinister interpretation of Walter’s death was inevitably suggested by the fact of his recent hostilities against his host.

One check to the success of William’s plans followed hard on the death of Walter and Biota. Margaret, the destined bride of Robert of Normandy, died before the marriage could be consummated. In 1063 Robert himself could not have been more than nine years old; while, although Margaret must have reached the age of twelve, the whole course of the history suggests that she was little more than a child, a fact which somewhat tends to discount the pious legend, in which our monastic informants revel, that the girl shrank from the thought of marriage and had already begun to practise the austerities of the religious profession. She left two sisters both older than herself, whose marriage alliances are important for the future history of Maine[87]; but their claims for the present were ignored, and William himself adopted the title of count of Maine.

Somewhere about the time of these events (the exact date is unknown) William was seized with a severe illness, which brought him to the point of death. So sore bestead was he that he was laid on the ground as one about to die, and in his extreme need he gave the reliquary which 137accompanied him on his progresses to the church of St. Mary of Coutances. No chronicler has recorded this episode, of which we should know nothing were it not that the said reliquary was subsequently redeemed by grants of land to the church which had received it in pledge; yet the future history of France and England hung on the event of that day.[88]

It was probably within a year of the settlement of Maine that William engaged in the last war undertaken by him as a mere duke of the Normans, the Breton campaign which is commonly assigned to the year 1064. As in the earlier wars with Anjou, a border dispute seems to have been the immediate occasion of hostilities, though now as then there were grounds of quarrel between the belligerents which lay deeper. Count Alan of Rennes, William’s cousin and guardian, had been succeeded by his son Conan, who like his father was continually struggling to secure for his line the suzerainty of the whole of Brittany as against the rival house of the counts of Nantes, a struggle which, under different conditions and with additional competitors at different times had now been going on for more than a century. The county of Nantes at this particular time was held by a younger branch of the same family, and there are some slight indications that the counts of Nantes, perhaps through enmity to their northern kinsmen, 138took up a more friendly attitude towards Normandy than that adopted by the counts of Rennes. However this may be, Count Conan appears in the following story as representing Breton independence against Norman aggression; and when William founded the castle of Saint James in the south-west angle of the Avranchin as a check on Breton marauders, Conan determined on an invasion of Normandy, and sent word to William of the exact day on which he would cross the border.

By the majority of Frenchmen it would seem that Brittany was regarded as a land inhabited by savages; in the eleventh century the peninsula stood out as distinct from the rest of France as it stands to-day. Its inhabitants had a high reputation for their courage and simplicity of life, but they were still in the tribal stage of society, and their manners and customs were regarded with abhorrence by the ecclesiastical writers of the time. Like most tribal peoples they had no idea of permanent political unity; and the present war was largely influenced by the fact that within the county of Rennes a Celtic chief named Rhiwallon was holding the town of Dol against his immediate lord on behalf of the duke of Normandy.[89] Instead of invading Normandy as he had threatened, Conan was driven to besiege Dol, and it was 139William’s first object in the campaign to relieve his adherent there.

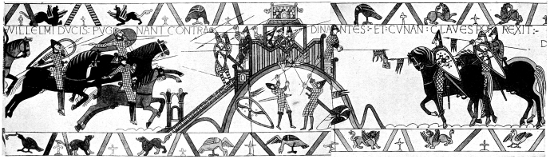

What gives exceptional interest to the somewhat unimportant expedition which followed is the undoubted presence in William’s army of his future rival for the crown of England, Harold the earl of Wessex.[90] The reason for, and the incidents connected, with, his visit to Normandy will have to be considered in a later chapter, but there cannot be any question as to its reality; and in a famous section, the Bayeux tapestry, our best record of this campaign, shows us Harold rescuing with his own hand a number of Norman soldiers who were being swept away by the Coesnon as the army crossed the border stream of Brittany. On the approach of the Norman army Conan abandoned the siege of Dol and fell back on his capital of Rennes; but relations soon seem to have become strained between Rhiwallon and his formidable ally, for we find Rhiwallon remarking to William that it mattered little to the country folk around Dol whether their substance were to be consumed by a Norman or a Breton army. Possibly it may have been the remonstrances of Rhiwallon which 140induced William to retire beyond the Norman border, but we are told that as he was in the act of leaving Brittany word was brought to him that Geoffrey (le Barbu) count of Anjou had joined himself to Conan with a large army and that both princes would advance to fight him on the morrow. It does not appear that William gave them the opportunity, but the tapestry records what was probably a sequel to this campaign in the section which represents William as besieging Conan himself in the fortress of Dinan. From the picture which displays Conan surrendering the keys of the castle on the point of his spear to the duke it is evident that the place was taken, but we know nothing of the subsequent fortunes of the war nor of the terms according to which peace was made. Within two years of these events, if we are right in assigning them to 1064, Conan died suddenly,[91] and was succeeded by his brother-in-law Hoel, count of Cornouaille, who united in his own person most of the greater lordships into which Brittany had hitherto been divided.

THE SIEGE OF DINANT FROM THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY

It may be well at this point briefly to review the position held by William at the close of 1064. With the exception of his father-in-law of Flanders, 141no single feudatory north of the Loire could for a moment be placed in comparison with him. Anjou and the royal demesne itself were, for different reasons, as we have seen, of little consequence at this time. The influence of Champagne under its featureless rulers was always less than might have been expected from the extent and situation of the county; and just now the attention of Count Theobald III. was directed towards the recovery of Touraine from the Angevin claimants rather than towards any rivalry with the greater power of Normandy. Brittany indeed had just shown itself hostile, but the racial division between Bretagne Brettonante and the Gallicised east, which always prevented the duchy from attaining high rank among the powers of north France, rendered it quite incapable of competing with Normandy on anything like equal terms. With the feudal lords to the east of the Seine and upper Loire William had few direct relations, but they, like the princes of Aquitaine, had received a severe lesson as to the power of Normandy in the rout of the royal army which followed the surprise of Mortemer. On the other hand, Normandy, threaded by a great river, with a long seaboard and good harbours, with a baronage reduced to order and a mercantile class hardly less prosperous than the men of the great cities of Flanders, would have been potentially formidable in the hands of a ruler of far less power than the future conqueror of England. Never before 142had Normandy attained so high a relative position as that in which she appears in the seventh decade of the eleventh century; and, kind as was fortune to the mighty enterprise which she was so soon to undertake, its success and even its possibility rested on the skilful policy which had guided her history in the eventful years which had followed Val-es-dunes.

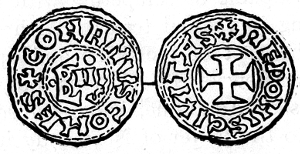

Denier of Conan II. of Brittany

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content