Search london history from Roman times to modern day

With the peace of Blanchelande we enter upon the last phase in the life of William the Conqueror, and this although more than the half of his English reign still lay in the future. It must be owned that no unity of purpose or achievement can be traced underlying this final stage; the history of these last years is little more than a series of disconnected episodes, of which the details themselves are very imperfectly known to us. It has, in fact, been customary for historians to regard this period as marking somewhat of a decline in the character and fortunes of the Conqueror; a decline which the men of the next generation were inclined to attribute to supernatural vengeance pursuing the king for his execution of Earl Waltheof in 1076. “Such was his resolution,” says Orderic, “that he still maintained a brave fight against his enemies, but success did not crown his enterprises now as formerly, nor were his battles often crowned with victory.”[264] This idea of retributive fate, characteristic of the medieval mind, has received from historians various adaptations and exemplifications, 345but perhaps a more reasonable explanation of the tameness of the last years of the Conqueror would be that the achievements of the decade between 1060 and 1070 inevitably make the succeeding history something of an anticlimax. The Conqueror’s last wars are indeed inconsiderable enough when compared with the campaigns of Le Mans and Hastings, but the most unique undertaking of his life falls within two years of its close; and with the Domesday Survey before us we need no further proof that the far-sightedness of the king’s policy and the strength of his executive power were still unimpaired at the very close of his career.

The main cause of the difficulties which beset the King in these latter years was the undutiful eagerness of Robert of Normandy to anticipate his inheritance. It was natural enough that Robert should wish to enjoy the reality of power; for a dozen years at least he had been the recognised heir of Normandy, and the peace of Blanchelande had recently assigned him the county of Maine. But so early as 1074 the earls of Hereford and Norfolk, in planning their revolt, are understood to have reckoned the disagreement between the King and his eldest son among the chances in their favour,[265] and it is certain that Robert had been bitterly discontented with his position for some time before he broke out into open revolt. The chronology of his movements 346is far from clear; but at some time or other he made a wild attempt to seize the castle of Rouen, and when this failed he found an immediate refuge and base of operations in the land of Hugh de Châteauneuf, a powerful lord on the border between Normandy and the royal demesne, who allowed him to occupy his castles of Raimalast, Sorel, and Châteauneuf. King William, on his part, confiscated the lands of the rebels; he also took into his pay Count Rotrou of Mortagne, the overlord of Hugh of Châteauneuf for Raimalast; and Robert was soon driven to seek a more distant exile in foreign parts. He first visited Flanders, but Robert the Frisian, notwithstanding his enmity towards his formidable brother-in-law, did not think it worth while to spend his resources upon his irresponsible nephew, for the latter is represented as wandering vaguely over Touraine, Germany, Aquitaine, and Gascony in great destitution. To such straits was he reduced, that his mother provoked the one dispute which varied the domestic peace of the Conqueror’s married life by sending supplies to her son in exile. The king, on discovering this, became convulsed with rage, poured reproaches on his queen for her support of a rebel, and ordered one of her messengers, who happened to be within his power, to be seized and blinded. The latter, however, a Breton named Samson, received a timely hint of his danger from persons in the confidence of the queen, and took refuge in the 347monastery of St. Evroul, “for the safety alike of his soul and body,” says Ordericus Vitalis, who for some forty years was his fellow-inmate in the abbey.

At last King Philip took pity upon the fugitive Robert and allowed him to establish himself in the castle of Gerberoi in the Beauvaisis. The king’s patronage of Robert ranks, as a matter of policy, with his gift of Montreuil to Edgar the Etheling in 1074; Philip was always ready to take an inexpensive opportunity of harassing his over-mighty vassal. Around Robert, in this cave of Adullam, there gathered a force of adventurers from Normandy and the French kingdom, including many men who had hitherto been good subjects to King William, but now thought it expedient to follow the rising fortunes of his heir. William retaliated by garrisoning the Norman castles which lay nearest to Gerberoi, so as to prevent the rebels from harrying the border; and in some way he must have brought the king of France over to his side; for when, in the last days of 1078, he laid formal siege to his son’s castle, we know on good authority that King Philip was present in his camp.[266] The siege lasted for three weeks, and in one of the frequent encounters between the loyalists and the rebels 348there occurred the famous passage of arms between the Conqueror and his son. William was wounded in the hand by Robert, his horse was killed under him, and had not a Berkshire thegn, Tokig, son of Wigod of Wallingford, gallantly brought another mount to the king,[267] it is probable that his life would have come to an ignominious close beneath the walls of Gerberoi. It was very possibly the scandal caused by this episode which led certain prominent members of the Norman baronage to offer their mediation between the king and his heir. The siege seems to have been broken up by mutual consent; William retired to Rouen, Robert made his way once more into Flanders, and a reconciliation was effected by the efforts of Roger de Montgomery, Roger de Beaumont, Hugh de Grentemaisnil, and other personal friends of the king. Robert was restored to favour, his confederates were pardoned, and he once more received a formal confirmation of his title to the duchy of Normandy. For a short time, as charters show, he continued to fill his rightful place at his father’s court, but his vagabond instincts soon became too strong for him and he left the duchy again, not to return to it during his father’s lifetime.

One is naturally inclined to make some comparison between these events and the rebellion which a hundred years later convulsed the dominions of Henry II. Fundamentally, the cause of 349each disturbance was the same—the anxiety of the reigning king to secure the succession, met by equal anxiety on the part of the destined heir to enjoy the fruits of lordship. And in each case the character of the respective heirs was much the same. Robert Curthose and Henry Fitz Henry, both men of chivalry, rather than of politics, showed themselves incapable of appreciating the motives which made their fathers wish to maintain the integrity of the family possessions; the fact that they themselves were debarred from rewarding their private friends and punishing their enemies, seemed to them a sufficient reason for imperilling the results of the statesmanship which had created the very inheritance which they hoped to enjoy. Robert of Normandy, a gross anticipation of the chivalrous knight of later times, represents a type of character which had hitherto been unknown among the sons of Rollo, a type for which there was no use in the rough days when the feudal states of modern Europe were in the making, and which could not attain any refined development before the Crusades had lifted the art and the ideals of war on to a higher plane. William the Conqueror, by no means devoid of chivalrous instincts, never allowed them to obscure his sense of what the policy of the moment demanded; Henry II. was much less affected by the new spirit; both rulers alike were essentially out of sympathy with sons to whom great place meant exceptional 350opportunities for the excitement and glory of military adventure, rather than the stern responsibilities of government.

We know little that is definite about the course of events which followed upon the reconciliation of King William and his heir. The next two years indeed form a practical blank in the personal history of the Conqueror, and it does not seem probable that he ever visited England during this interval. In his absence the king of Scots took the opportunity of spreading destruction once again across the border, and in the summer of 1079 he harried the country as far as the Tyne, without hindrance, so far as our evidence goes, from the clerical earl of Northumbria. The success of this raid was a sufficient proof of the weakness of the Northern frontier of England, and in the next year[268] Robert of Normandy was entrusted with the command of a counter-expedition into Scotland, with orders to receive the submission of the king of Scots, or, in case he proved obdurate, to treat his land as an enemies’ country. The Norman army penetrated Scotland as far as Falkirk, and, according to one account, received hostages as a guarantee of King Malcolm’s obedience. Another and more strictly contemporary narrative, however, states that this part of the expedition was fruitless; but, in any case, Robert on his return founded the great fortress of Newcastle-on-Tyne as a barrier 351against future incursions from the side of Scotland.

Some information as to William’s own movements in Normandy during 1080 may be gathered from charters and other legal documents. On the 7th of January he was at Caen,[269] and on the 13th he appears at Boscherville on the Seine[270]; at Easter he held a great court probably at Rouen.[271] At Whitsuntide he presided over a council at Lillebonne,[272] where a set of canons was promulgated which strikingly illustrates his opinion as to the relations which should exist between church and state.

Whitsunday in 1080 fell on the 31st of May, and serious disturbances had been taking place in England earlier in the month. Bishop Walcher of Durham had proved an unpopular as well as an inefficient earl of Northumbria. Himself a foreigner and a churchman, he must from the outset have been out of touch with the wild Englishmen placed under his rule, and the situation was aggravated by the fact that the bishop’s priestly office compelled him to transact the work of government in great part by deputy. He entrusted the administration of his earldom to a kinsman of his own called Gilbert,[273] and in all matters of business he relied on the counsel of an ill-assorted 352pair of favourites, one of them a noble Northumbrian thegn called Ligulf, who found his way to his favour by the devotion which he professed to Saint Cuthbert, the other being his own chaplain, Leobwine, a foreigner. Jealousy soon broke out between the thegn and the chaplain, and at last the latter, being worsted by his rival in a quarrel in the bishop’s presence, took the above mentioned Gilbert into his confidence and prevailed on him to destroy the Englishman secretly. On hearing the news the bishop was struck with dismay, and, in his anxiety to prove his innocence, summoned a general meeting of the men of his earldom to assemble at Gateshead. The assembly came together, but the Bernicians were in a dangerous humour; the bishop dared not risk a deliberation in the open air, and took refuge in the neighbouring church. Instantly the gathering got out of hand, the church was surrounded and set on fire, and the bishop and his companions were cut to pieces by the mob.

For such an act as this there could be no mercy. The punishment of the murderers was left to Walcher’s fellow-prelate Odo of Bayeux, and the vengeance which he took was heavy. It must have been impossible to determine with accuracy the names of those who had actually joined in the crime, but it is evident that men from all parts of Bernicia had taken part in the meeting at Gateshead, and the whole earldom was held implicated in the murder. Accordingly the 353whole district was ravaged, and the bishop of Bayeux administered death and mutilation on a scale unusual even in the eleventh century.[274] To the thankless dignity of the Northumbrian earldom, the Conqueror appointed Aubrey de Coucy, a powerful Norman baron; but he soon abandoned the task of governing his distressful province and retired to his continental estates. To him there succeeded Robert de Mowbray, who was destined to be the last earl of Bernicia, but who proved more successful than any of his predecessors in the work of preserving order and watching the movements of the king of Scots; and for the next ten years Northumbria under his stern rule ceases to trouble the central administration.

The chief interest of the following year in the history of the Conqueror lies in the singular expedition which he made at this time beyond the limits of his immediate rule into the extreme parts of Wales. The various but scanty accounts of this event which we possess are somewhat conflicting. The Peterborough chronicler says that the king “in this year led an army into Wales and there freed many hundred men.” The Annales Cambriæ tell us that “William, king of the English, came to St. David’s that he might pray there.” Very possibly the Conqueror did in reality pay his devotions at the 354shrine of the apostle of Wales, but secular motives were not lacking for an armed demonstration in that restless land. So long as the Normans in England itself were only a ruling minority, holding down a disaffected population, the conquest of Wales was an impossibility; and yet on all grounds it was expedient for the king to show the Welshmen what reserves of power lay behind his marcher earls of Shrewsbury and Chester. The expedition has a further interest as one of the earliest occasions on which it is recorded that the feudal host of England was called to take the field; the local historian of Abingdon abbey remarked that nearly all the knights belonging to that church were ordered to set out for Wales, although the abbot remained at home.[275] It does not appear that any of the native princes of South Wales suffered displacement at this time; the one permanent result of the expedition would seem to have been the foundation of Cardiff castle[276] as an outpost in the enemies’ land. The strategical frontier of England in this quarter consisted of the line of fortresses which guarded the lower course of the Wye, and the settlement of the Welsh question, like the settlement of the Scotch question, was a legacy which the Conqueror left to his successors.

After these events, but not before the end of the year, King William withdrew into Normandy, 355and probably spent the greater part of 1082 in his duchy. But his return to England was marked by one of the most dramatic incidents in his whole career, the famous scene of the arrest of Odo, bishop of Bayeux and earl of Kent. Up to the very moment of the bishop’s fall, the relations between the brothers appear to have been outwardly friendly, and in an English charter of the present year, the bishop appears at court in full enjoyment of his lay and spiritual titles.[277] The cause of the final rupture is uncertain. Ordericus Vitalis[278] assigned it to the unprecedented ambition of Bishop Odo, who, not content with his position in England and Normandy, was supposed to be laying his plans to secure his election to the papal chair at the next vacancy. According to this tale, the bishop had bought himself 356a palace in Rome, bribed the senators to join his side, and engaged a large number of Norman knights, including no less a person than the earl of Chester, to follow him into Italy when the time for action came. Whatever Odo’s plans may have been, William received news of them in Normandy, and he hurried across the Channel, intercepting Odo in the Isle of Wight. Without being actually arrested, Odo was placed under restraint, and a special sitting of the Commune Concilium was convened to try his case. The subsequent proceedings were conducted in the Isle of Wight, very possibly in the royal castle of Carisbrooke, and King William himself seems to have undertaken his brother’s impeachment. The articles laid against Odo fell into two parts, a specific charge of seducing the king’s knights from their lawful duty, and a general accusation of oppression and wrong-doing to the church and to the native population of the land. The task of giving judgment on these points belonged by customary law to the barons in council, but they failed to give sentence through fear of the formidable defendant before them, and the Conqueror himself was compelled to issue orders for Odo’s arrest. Here another difficulty presented itself, for no one dared lay hands on a bishop; and upon William seizing his brother with his own hands, Odo cried out, “I am a bishop and the Lord’s minister; a bishop may not be condemned without the judgment of the Pope.” To this claim of episcopal 357privilege William replied that he arrested not the bishop of Bayeux, but the earl of Kent, and Odo was sent off straightway in custody to the Tower of Rouen. At a later date it was suggested that the distinction between the bishop’s lay and spiritual functions was suggested to the king by Lanfranc,[279] whose opinion as an expert in the canon law was incontrovertible; and apart from the dramatic interest of the scene the trial of Odo has special importance as one of the few recorded cases in which a question of clerical immunity was raised before the promulgation of the Constitutions of Clarendon.

The one extended narrative which we possess of these events was composed some forty years after the date in question, and the scheme which is attributed to Bishop Odo may well seem too visionary a project to have been undertaken by that very hard-headed person, yet on the whole we shall probably do well to pay respect to Orderic’s version of the incident. For, although the militant lord of Bayeux might seem to us an incongruous successor for the saintly Hildebrand, it must as yet have been uncertain how far the church as a whole had really identified itself with the ideals which found their greatest exponent in Gregory VII., and the situation in Italy itself was such as to invite the intervention of a prelate capable of wielding the secular arm. The struggle between pope and emperor was at its height, 358and within three years from the date of Odo’s arrest Hildebrand himself was to die in exile from his city, while Norman influence was all-powerful in south Italy. The tradition represented in Orderic’s narrative shows an appreciation of the general situation, and if we regard the motive assigned for Odo’s preparations as merely the monastery gossip of the next generation, yet the bishop’s imprisonment is a certain fact, and the unusual bitterness of King William towards his half-brother would suggest that something more than political disloyalty gave point to the latter’s schemes. Nevertheless the captivity in which Bishop Odo expiated his ambition cannot have been enforced with very great severity, for in the five years which intervened between his disgrace and William’s death he appears at least occasionally in attendance at his brother’s court.

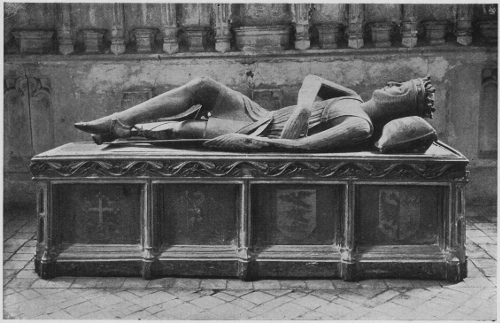

The circle of the Conqueror’s immediate companions was rapidly breaking up now. On November 3rd, 1083, Queen Matilda died, and was buried in the convent of the Holy Trinity at Caen, which she had founded in return for her lord’s safety amid the perils of his invasion of England. Archbishop Lanfranc and Earl Roger of Montgomery almost alone represented the friends of King William’s early manhood at the councils of his last four years. Through all the hazards of her married life Matilda of Flanders had played her part well; if William the Conqueror 359alone among all the men of his house kept his sexual purity unstained to the last, something at least of this may be set down to his love for the bride whom he had won, thirty years before, in defiance of all ecclesiastical censure. Nor should Matilda’s excellence be conceived of as lying wholly in the domestic sphere; William could leave his duchy in her hands when he set out to win a kingdom for himself and her, and William was no contemptible judge of practical ability in others. We shall hardly find in all English medieval history another queen consort who takes a place at once more prominent and more honourable.

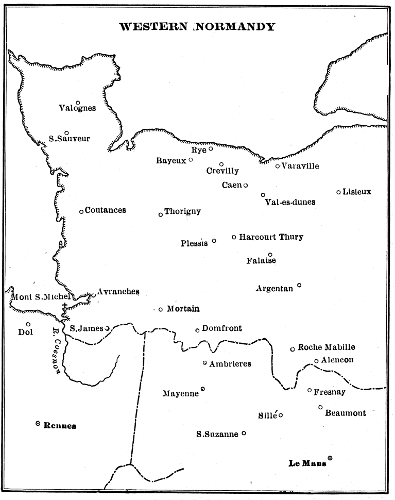

In the year following Queen Matilda’s death, the Conqueror’s attention was for the last time concentrated on the affairs of Maine, and in a manner which illustrates the uncertain tenure by which the Normans still held their southern dependency. Twenty years of Norman rule had failed to reconcile the Manceaux to the alien government. The rising of 1073 had proved the strength and extent of the disaffection, and from the events of the present year it is plain that the Norman element in Maine was no more than a garrison in hostile territory, although the disturbance which called William into the field in 1084 was merely the revolt of a great Mancel baron fighting for his own hand, which should not be dignified with the name of a national movement. In the centre of the county the castle of Sainte-Suzanne stands on a high rock overlooking the 360river Arne, one of the lesser tributaries of the Sarthe. This fortress, together with the castles of Beaumont and Fresnay on the greater river, belonged to Hubert the viscount of Maine, who had been a prominent leader of the Mancel nationalists in the war of 1063, and had subsequently married a niece of Duke Robert of Burgundy. Formidable alike from his position in Maine and his connection with the Capetian house, Hubert proved himself an unruly subject of the Norman princeps Cenomannorum and after sundry acts of disaffection he broke into open revolt, abandoned his castles of Fresnay and Beaumont, and concentrated his forces on the height of Sainte-Suzanne. Like Robert of Normandy at Gerberoi, five years before, Hubert made his castle a rendezvous for all the restless adventurers of the French kingdom, who soon became intolerable to the Norman garrisons in Le Mans and its neighbourhood. The latter, it would seem, were not strong enough to divide their forces for an attack on Sainte-Suzanne, and sent an appeal for help to King William, who thereupon gathered an army in Normandy, and made ready for his last invasion of Maine.

WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

(AS CONCEIVED BY A FRENCH PAINTER OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY)

THE ORIGINAL OF THIS PICTURE, NOW LOST, WAS PAINTED BY AN ARTIST WHEN THE TOMB OF THE CONQUEROR WAS OPENED IN 1522. A COPY EXECUTED IN 1708, IS PRESERVED IN THE SACRISTY OF ST. ETIENNE’S CHURCH AT CAEN; THE PRESENT ILLUSTRATION IS FROM A PHOTOGRAPH OF THAT COPY

WESTERN NORMANDY

But for once in his life the Conqueror found himself confronted by an irreducible fortress. “He did not venture to lay siege to the castle of Sainte-Suzanne,” says Orderic,

“it being rendered impregnable by its position on 361rocks and the dense thickets of vineyards which surrounded it, nor could he confine the enemy within the fortress as he wished, since the latter was strong enough to control supplies and was in command of the communications. The king therefore built a fortification in the valley of Bonjen, and placed therein a strong body of troops to repress the raids of the enemy, being himself compelled to return into Normandy on weighty affairs.”[280]

As William had no prospect of reducing the castle, either by storm or blockade, he was well advised to save his personal prestige by retreat, but the garrison of his counterwork under his lieutenant Alan Earl of Richmond proved themselves unequal to the task assigned them. For three years, according to Orderic, the operations in the Arne valley dragged on, and the fame of Hubert’s successful resistance attracted an increasing stream of volunteers from remote parts of France. At last, when many knights of fame had been killed or taken prisoner, the disheartened Normans at Bonjen resolved to bring about a reconciliation between the king and the viscount. William was in England at the time, and on receiving details of the Norman losses before Sainte-Suzanne he showed himself willing to come to terms with Hubert, who thereupon crossed the Channel under a safe conduct and was restored to favour at the royal court.[281]

362With this failure closes the record of the Conquerors achievements in Maine. The events of the next ten years proved that the triumph of Hubert of Sainte-Suzanne was more than the accidental success of a rebellious noble; a national force lay behind him and his crew of adventurers, which came to the front when Helie de la Flèche struggled for the county of Maine with William Rufus. In the process which during the next half-century was consolidating the feudal world of France, Maine could not persist in isolated independence, but its final absorption into Anjou was less repugnant to local patriotism and the facts of geography than its annexation by the lords of Rouen. Those who have a taste for historical parallels may fairly draw one between William’s wars in Maine and his descendant Edward I.’s attack on the autonomy of Scotland, with reference to the manner in which an initial success was reversed after the death of the great soldier who had won it, by the irreconcilable determination of the conquered people. But there lies a problem which cannot be wholly answered in the question why King William’s work, so permanent in the case of England, was so soon undone in the case of the kindred land of Maine.

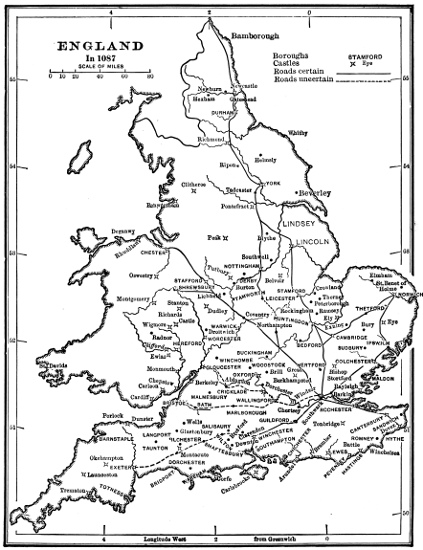

It is possible that the Conqueror’s placability 363toward Hubert of Sainte-Suzanne was not unconnected with a more formidable danger threatening England from the north and east. Once more the Scandinavian peril hung over the land. Harold of Denmark, the eldest son of Swegn Estrithson, had died in 1080, and his brother and successor Cnut married the daughter of William’s inveterate enemy, Count Robert of Flanders. In this way a family alliance between the two strongest naval powers of the north was called into being; and in 1085 the king and the count planned a joint invasion of England. Cnut attempted to draw King Olaf of Norway into the expedition, and received from him a contingent of sixty ships, but Olaf would not join in person, giving as his reason that the kings of Norway had always been less successful than the kings of Denmark in enterprises against England, and that his kingdom had not yet recovered from the disaster of 1066.[282] But now, as in the former year, England had no fleet available for serious naval operations; and King William’s subjects must have thought that his defensive measures were as ruinous to the districts affected as the passage of an invading army itself. The king was in Normandy when he became apprised of the danger, and he hastened across the Channel, with a great force of French and Breton mercenaries, “so that people wondered how the land could feed all that army,” remarks the 364Peterborough chronicler. The king arranged for the billeting of the host among his barons, and then proceeded deliberately to lay waste the parts of the country exposed to attack; a precaution which would have kept the enemy from advancing far from the coast, but which must have cruelly afflicted the poorer folk of the eastern shires.[283] Meanwhile a great armament from Flanders and Denmark had been gathered in the Lijm fiord, and all was ready for the voyage when on July 10, 1086, Cnut was murdered in the church of Odensee.[284] His death meant the abandonment of the expedition, but is probable that his abortive schemes contributed to one of the most notable events of William’s reign—the oath of Salisbury of 1086.

The king had kept the feast of 1086 at Winchester and had knighted his youngest son, Henry, in the Whitsuntide council at Westminster. Not long afterwards he turned westward again, and by the first of August had come to Salisbury, where he held an assembly of very exceptional character. “There his Witan came to him,” says the Anglo-Saxon chronicler, “and all the landholding men in England, no matter whose men they might be, and swore him fealty that they 365would be true to him against all men.”[285] The native chronicler in his cell at Peterborough was evidently impressed by the scale of all the Conqueror’s measures in these last years, and his statement that all the land-holding men in England came to the Salisbury meeting must not be construed too literally, but he has seen clearly enough what was the real purpose of the famous oath. It was no slight matter that King William was strong enough to exact from each mesne tenant in his kingdom an absolute oath of allegiance to himself in person, without explicit reference to the tie of homage which bound individual tenants to their immediate lords. But, significant as is this clear enunciation of the principle that the king’s claim to fealty overrides the lord’s claim to service, it should not be taken to imply any revolutionary change in the current doctrines of feudal law. It is highly probable that this general oath was demanded with the single purpose of providing against the defection of disloyal knights and barons to Cnut of Denmark in the imminent event of his landing. News travelled slowly in the eleventh century, and King William at Salisbury on August 1st could not well have heard of the murder at Odensee on July 10th. But apart from this, any feudal monarch could have maintained in theory that the facts of subinfeudation should not invalidate his sovereign rights; the question was merely 366as to the possibility of enforcing the latter. The exceptional power enjoyed by William and his successors in this respect was due to the intimate relations established between the king and his feudatories by the circumstances of the Conquest; the Oath of Salisbury was a striking incident and little more.

It was probably not long after the famous scene at Salisbury that the Conqueror crossed the Channel for the last time. No chronicler has recorded the name of the port which witnessed King William’s last embarkation, but we know that he called at the Isle of Wight on his way to Normandy, and we may suppose that he had set sail from some Hampshire or Sussex haven. His subjects probably rejoiced at his departure, for England had fallen on evil times in these last years. The summer of 1086 had been disastrous for a population never living far from the margin of subsistence. “This year was very grievous,” laments the native chronicler, “and ruinous and sorrowful in England through the murrain; corn and fruit could not be gathered and one cannot well think how wretched was the weather, there was such dreadful thunder and lightning, which killed many men, and always kept growing worse and worse. God Almighty amend it when it please him.” But the bad harvest brought its inevitable train of famine and pestilence, and 1087 was worse than 1086 had been. It was the agony of this year that called forth the famous 367picture of the Conqueror’s fiscal exactions, how the miserly king leased his lands at the highest rent that could be wrung out of the poor men by right or wrong; how his servants exacted unlawful tolls. Medieval finance was not elastic enough to adapt itself to the alternation of good and bad seasons; and in a time of distress men were crushed to the earth by rents and taxes, which, as Domesday Book shows, they could afford to bear well enough in years of normal plenty. The monk of Peterborough took no account of this, and yet he clearly felt that he had reached the climax of disaster as he recorded the death of William the Conqueror.

The question of the Vexin Française, which, by a singular chance, was to cost the Conqueror his life, originated in the days of Duke Robert of Normandy and Henry I. of France. We have seen that King Henry, in return for help given by Robert to him in the difficult time of his accession, ceded the Vexin Française to the Norman Duke. Drogo, the reigning count, remained true to the Norman connection, and accompanied Duke Robert to the Holy Land, where he died; but his son Walter wished to detach the Vexin from association with Normandy and to replace himself under the direct sovereignty of the king of France. He proved his hostility to William of Normandy in the campaign of Mortemer, and by the claims which he raised to the county of Maine in 1063, but he died without issue, and his 368possessions passed to his first cousin, Ralf III., count of Valois. The house of Valois was not unfriendly to Normandy, and from 1063 to 1077 its powerful possessions were a standing menace to the royal demesne. But in the latter year the family estates were broken up by a dramatic event. Simon de Crepy, the son of Count Ralf, who had successfully maintained his position against Philip I., felt nevertheless a desire to enter the religious life, and on his wedding night he suddenly announced his determination, persuaded his young bride to follow his example, and retired from the world. Philip I. thereupon reunited the Vexin to the royal demesne without opposition from William of Normandy, who was at the time much occupied with the affairs of Maine.[286] For ten years William acquiesced in the state of affairs, and his present action took the form of a reprisal for certain raids which the Frenchmen in Mantes had lately been making across the Norman border. It would clearly have been useless to expect King Philip to intervene, and William accordingly raised the whole Vexin question once more, and demanded possession of Pontoise, Chaumont, and Mantes, three towns which command the whole province.

It does not seem that Philip made any attempt to defend his threatened frontier, and he is reported to have treated William’s threats with contempt. Thereupon, the Conqueror, stung by 369some insult which passed at the time, suddenly threw himself with a Norman force across the Epte, and harried the country until he came to Mantes itself. The garrison had left their posts on the previous day, in order to inspect the devastation which the Normans had wrought in the neighbourhood, and were surprised by King William’s arrival. Garrison and invaders rushed in together headlong through the gates of the city, but the Normans had the victory, and Mantes was ruthlessly burned. And then King William, while riding among the smouldering ruins of his last conquest, in some way not quite clearly known, was thrown violently upon the pommel of his saddle, and his injury lay beyond the resources of the rough surgery of the eleventh century.

Stricken thus with a mortal blow, King William left the wasted Vexin for his capital of Rouen, and for six weeks of a burning summer his great strength struggled with the pain of his incurable hurt. At first he lay within the city of Rouen itself, but as the days passed he became less able to bear the noise of the busy port, and he bade his attendants carry him to the priory of Saint-Gervase, which stands on a hill to the west of the town. The progress of his sickness left his senses unimpaired to the last, and in the quiet priory the Conqueror told the story of his life to his sons William and Henry, his friend and physician Gilbert Maminot, bishop of Lisieux, 370Guntard, abbot of Jumièges, and a few others who had come to witness the end of their lord. Two independent narratives of King William’s apologia have survived to our day, and, although monastic tradition may have framed the tale somewhat to purposes of edification, yet we can see that it was in no ignoble spirit that the Conqueror, under the shadow of imminent death, reviewed the course of his history. He called to mind with satisfaction his constant devotion and service to Holy Church, his patronage of learned men, and the religious houses founded under his rule. If he had been a man of war from his youth up he cast the blame in part upon the disloyal kinsmen, the jealous overlord, the aggressive rivals who had beset him from his childhood, but for the conquest of England, in this his supreme moment, he attempted no justification. In his pain and weariness, the fame he had shed upon the Norman race paled before the remembrance of the slaughter at Hastings, and the harried villages of Yorkshire. No prevision, indeed, of the mighty outcome of his work could have answered the Conqueror’s anxiety for the welfare of his soul, and under the spur of ambition he had taken a path which led to results beyond his own intention and understanding. We need not believe that the bishop of Lisieux or the abbot of Jumièges have tampered with William’s words, when we read his repentance for the events which have given him his place in history.

371It remained for the Conqueror to dispose of his inheritance, and here for once political expediency had to yield to popular sentiment. We cannot but believe that the Conqueror, had it been in his power, would have made some effort to preserve the political union of England and Normandy. But fate had struck him down without warning, and ruled that his work should be undone for a while. With grim forebodings of evil William acknowledged that the right of the first-born, and the homage done by the Norman barons to Robert more than twenty years before, made it impossible to disinherit the graceless exile, but England at least should pass into stronger hands. William Rufus was destined to a brief and stormy tenure of his island realm, but its bestowal now was the reward of constant faithfulness and good service to his mighty father. To the English-born Henry, who was to be left landless, the Conqueror bequeathed five thousand pounds of silver from his treasury, and, in answer to his complaint that wealth to him would be useless without land, prophesied the future reunion of the Anglo-Norman states under his rule. And then, while Henry busied himself to secure and weigh his treasure, the Conqueror gave to William the regalia of the English monarchy, and sealed a letter recommending him to Archbishop Lanfranc as the future king, and kissing him gave him his blessing, and directed him to hasten to England before men there knew that their lord was dead.

372In his few remaining hours King William was inspired by the priests and nobles who stood around his bed to make reparation to certain victims of his policy, who still survived in Norman prisons. Among those who were now released at his command were Wulfnoth, Earl Godwine’s son, and Wulf the son of King Harold; the prisoners of Ely, Earl Morcar and Siward Barn; Earl Roger of Hereford, and a certain Englishman named Algar. Like ghosts from another world these men came out into the light for a little time before they vanished finally into the dungeons of William Rufus; but there was one state prisoner whose pardon, extorted reluctantly from the Conqueror, was not reversed by his successor. It was only the special intercession of Count Robert of Mortain which procured the release of his brother, Bishop Odo. The bishop had outdone the Conqueror in oppression and cruelty to the people of England, and regret for his own sins of ambition and wrong had not disposed the king for leniency towards his brother’s guilt in this regard. At length in sheer weariness he yielded against his will, foretelling that the release of Odo would bring ruin and death upon many.

It is in connection with Bishop Odo’s liberation that Orderic relates the last recorded act of William’s life. A certain knight named Baudri de Guitry, who had done good service in the war of Sainte-Suzanne, had subsequently offended the 373king by leaving Normandy without his license to fight against the Moors in Spain. His lands had been confiscated in consequence, but were now restored to him, William remarking that he thought no braver knight existed anywhere, only he was extravagant and inconstant, and loved to wander in foreign countries. Baudri was a neighbour and friend to the monks of St. Evroul, hence no doubt the interest which his restoration possessed for Ordericus Vitalis.

In the final stage of King William’s sickness, the extremity of his pain abated somewhat, and he slept peacefully through the night of Wednesday the 8th of September. As dawn was breaking he woke, and at the same moment the great bell of Rouen cathedral rang out from the valley below Saint-Gervase’s priory. The king asked what it meant; those who were watching by him replied, “My lord, the bell is tolling for primes at St. Mary’s church.” Then the Conqueror, raising his hands, exclaimed: “To Mary, the holy mother of God, I commend myself, that by her blessed intercession I may be reconciled to her beloved Son, our Lord Jesus Christ.” The next instant he was dead.

For close upon six weeks the king had lain helpless in his chamber in the priory, but death had come upon him suddenly at last, and the company which had surrounded him instantly scattered in dismay. Each man knew that for many miles around Rouen there would be little 374security for life or property that day, and the dead king was left at the mercy of his own servants, while his friends rode hard to reach their homes before the great news had spread from the city to the open country. By the time that the clergy of Rouen had roused themselves to take order how their lord might be worthily buried, his body had been stripped, his chamber dismantled, and his attendants were dispersed, securing the plunder which they had taken. The archbishop of Rouen directed that the king should be carried to the church of his own foundation at Caen, but no man of rank had been left in the city, and it was only an upland knight, named Herlwin, who accompanied the Conqueror on his last progress over his duchy. By river and road the body was brought to Caen, and a procession of clergy and townsfolk was advancing to meet it, when suddenly a burst of flame was seen arising from the town. The citizens, who knew well what this meant among their narrow streets and wooden houses, rushed back to crush the fire, while the monks of Saint Stephen’s received the king’s body and brought it with such honour as they might to their house outside the walls.

ENGLAND In 1087

Shortly afterwards, the Conqueror was buried in the presence of nearly all the prelates of the Norman church. The bishop of Evreux, who had watched by the king’s death-bed, preached, praising him for the renown which his victories had brought upon his race, and for the strictness 375of his justice in the lands over which he ruled. But a strange scene then interrupted the course of the ceremony. A certain Ascelin, the son of Arthur, came forward and loudly declared that the place in which the grave had been prepared had been the court-yard of his father’s house, unjustly seized by the dead man for the foundation of his abbey. Ascelin clamoured for restitution, and the bishops and other magnates drew him apart, and, when satisfied that his claim was just, paid him sixty shillings for the ground where the grave was. And then, with broken rites, the Conqueror was laid between the choir and the altar of Saint Stephen’s church.

Denier of Philip I. of France

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content