Search london history from Roman times to modern day

The art of government in the eleventh century was still a simple, or at least an untechnical, matter. It demanded rather a strong will in the sovereign than professional knowledge in his ministers: the responsibility was the king’s, and his duty to his subjects was plain and recognised by all men. No one doubted that the maintenance of order was the king’s work, but the method of its performance was left to his discretion. It was not a light task, but it was a task which would be done the better the simpler were the agencies employed, the more immediately each act of government was felt to be the personal act of the head of the state. The time was not ripe for the highly specialised administration of Henry II.; it was bound to take more than twenty years before a trained body of administrators could be elaborated out of the transplanted Norman baronage, before the king had learned to whom he could safely entrust the permanent work of civil government. The Conqueror’s administration was by the nature of the case empirical; neither Normandy nor England had anything to offer in the way of centralised routine, but for all that it is from the simple 408expedients adopted by William that the medieval constitution of England takes its origin.

Just as in Normandy an indefinite body of “optimates” surrounded the duke, and expected to be consulted on occasions of special importance, so in England the king’s greater tenants, lay and ecclesiastical, formed a potential council, the “Commune Concilium” of later writers. The connection between the council in its English and Norman manifestations was something closer than mere similarity of composition; many a man who witnessed the coronation of Queen Matilda in the Easter Council of 1068 must have sat in the assembly at Lillebonne which discussed the invasion of England; and judging from the evidence of charters the barons who accompany the king when in Normandy will probably appear as lords of English fiefs in the pages of Domesday Book. Roger de Montgomery, Henry de Ferrers, Walter Giffard, Henry de Beaumont—such men as these, who were great on either side the Channel, appear in frequent attendance on their lord, whether at Rouen or at Winchester. Their attendance, indeed, was a guarantee of good faith; the baron who, when summoned, neglected to obey, became thereby a suspected person at once: it was considered a sign of disaffection when Earl Roger of Hereford persistently absented himself from William’s court.

In England we know that it was customary for the king to hold a great council thrice in each 409year. “Moreover” says the Peterborough chronicler, “he was very worshipful: he wore his crown thrice in every year when he was in England. At Easter he wore it at Winchester, at Whitsuntide at Westminster, at midwinter at Gloucester, and then there were with him all the great men of all England—archbishops and bishops, abbots and earls, thegns and knights”; “in order,” adds William of Malmesbury, “that ambassadors from foreign countries might admire the splendour of the assembly and the costliness of the feasts.” As it is only at these great seasons that the Commune Concilium comes practically into being; we may give a list of those known to be present at the Easter feast of 1069 and the Christmas feast of 1077, to which we may add a list of those in attendance on the king when he held his Easter feast of 1080 in Normandy.[296]

410It will be clear that an assembly of this kind is eminently unfitted to be the organ of systematic government. These great people, bishops, earls, and abbots, had their own work to do, work which for long periods kept them away from the king’s presence. The Commune Concilium is at most what its name implies, an advisory body. As such it plays the part taken in the Anglo-Saxon policy by the “Witan,” and the question arises whether it can be considered a continuation of that assembly under altered conditions and with restricted powers or whether it proceeds from some quite different principle.

It is plain that the Norman council is in no sense a popular assembly; we certainly cannot say of it, as has been said of the “Witan,” that “every free man had in theory the right to attend.” On the other hand it is probable that 411the alleged popular composition of the Witan is illusory, while the nature of the body which attended Edward the Confessor might be described equally with the Conqueror’s councils as consisting of “archbishops and suffragan bishops, abbots and earls, thegns and knights.” But it is probable that this similarity of constitution is only superficial. If pressed for a definition of the Commune Concilium we might, perhaps, venture to say that it consisted potentially of all those men who held in chief of the crown by military service, of those tenentes in capite whose estates in Domesday are entered under separate rubrics. This definition would include the great ecclesiastical tenants, while it would exclude the undistinguished crowd of sergeants (servientes) and king’s thegns, and it would suggest one most important respect in which the Commune Concilium differs from its Old English representative. All the members of the Norman council are united to the king by the strongest of all ties, the bond of tenure. That great change, in virtue of which every acre of land in England has come to be held mediately or immediately of the king, influences constitutional no less than social relations; the king’s council is a body composed of men who are his own tenants. From this technical distinction follows a difference of great importance; the king’s influence over his council becomes direct and inevitable to a degree impossible before the Conquest. Under Edward the Confessor it is 412not impossible for the Witan to be found going its own way with but scanty regard to the personal wishes of the king; under the Conqueror and his sons the king’s will is supreme. Most true is it that the three Norman kings were men of very different quality from the imbecile Edward; but nevertheless, the tenurial bond between the king and his barons made it impossible for the latter when in council to follow an independent political course. The Norman kings were wise enough to entertain advice and too strong for that advice ever to pass into dictation.

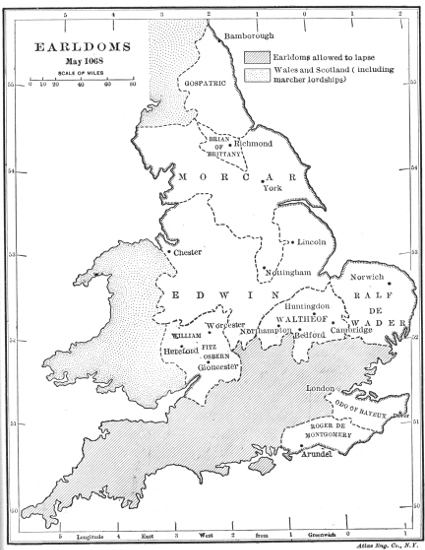

EARLDOMS

May 1068

Distinct then as is the Commune Concilium from the Witan, we nevertheless meet in the earliest years of William’s reign with certain assemblies which may fairly be considered as transitional forms between the two. Up to the last revolt of Edwin and Morcar not a few Englishmen continued to hold high positions at William’s court; and among the witnesses to the few charters of this date which have survived there still exists a fair proportion of English names. Such men as Edwin and Morcar themselves must have represented the independent traditions of the Old English Witan, and there are other names which are common to the latest charters of King Edward and the earliest charters of King William. As it is very rarely that we can obtain a glimpse of an assembly of this intermediate type we may subjoin a list of those in attendance on the king at or shortly after the 413Whitsuntide Council of 1069, taken from a charter restoring to the church of Wells lands which Harold, “inflamed with cupidity,” is said to have appropriated unjustly:

King William; Queen Matilda; Stigand, archbishop; Ealdred, archbishop; Odo, bishop of Bayeux; Hugh, bishop (of Lisieux); Herman, bishop (of Thetford); Leofric, bishop of Exeter; Ethelmer, bishop of Elmham; William, bishop of London; Ethelric, bishop of Selsey; Walter, bishop of Hereford; Remi, bishop of Lincoln; Ethelnoth, abbot of (Glastonbury); Leofweard, abbot of (Michelney); Wulfwold, abbot of Chertsey; Wulfgeat, abbot; Earl William; Earl Waltheof; Earl Edwin; Robert, the king’s brother; Roger, “princeps”; Walter Giffard; Hugh de Montfort; William de Curcelles; Serlo de Burca; Roger de Arundel; Richard, the king’s son; Walter the Fleming; Rambriht the Fleming; Thurstan; Baldwin “de Wailen leige”; Athelheard; Hermenc; Tofig, “minister”; Dinni; “Alfge atte Thorne”; William de Walville; Bundi, the Staller; Robert, the Staller; Robert de Ely; Roger “pincerna”; Wulfweard; Herding; Adsor; Brisi; Brihtric.[297]

Starting with the greatest persons in church and state the list gradually shades off to a number of obscure names, the bearers of which cannot be identified outside this record. Some of these last may be local people connected with the estates to which the grant refers, but most of 414even the English names can be recognised in the general history of the time. The peculiar value of the list is that it shows us Englishmen and Normans associated, apparently on terms of equality, at the Conqueror’s court. It is instructive to see the English earls of Northampton and Mercia signing between Earl William Fitz Osbern and Count Robert of Mortain; the fact that men whose names are among the greatest in Domesday Book are to be found witnessing the same document with men who had signed Edward the Confessor’s charters helps us to bridge the gulf which separates Anglo-Saxon from Norman England. But this phenomenon is confined to the years immediately succeeding the Conquest; very suddenly, after the date of this document, the English element at William’s court gives way and disappears, and with it disappear the names which unite the Old English “Witan” to the Norman “Concilium.” This is a fact to which we have already had occasion to refer, for the general change in William’s policy which occurs in 1070 affects every aspect of his history.

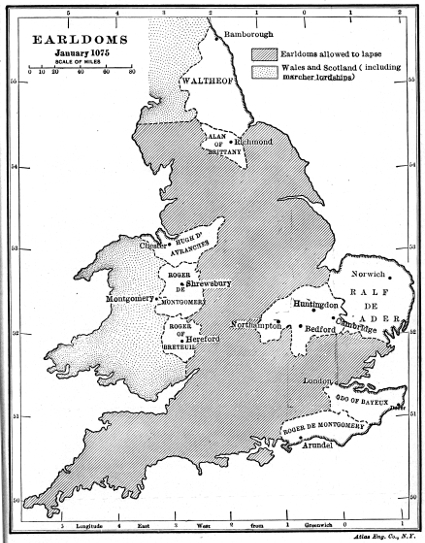

EARLDOMS

January 1075

The functions of this court or council seem to have been as indeterminate as its composition. Largely, no doubt, they were ceremonial; this aspect of the council was evidently in the mind of William of Malmesbury when he wrote the passage quoted on page [missing][missing]. At times it appears as a judicial body, Waltheof was condemned in the Midwinter Council of 1075; while of its advisory 415powers we have a supreme example in the “deep speech” at Gloucester, which led to the making of Domesday Book. If the title which is attached to the oldest copy of William’s laws has any validity, they were promulgated in accordance with Old English customs by the king cum principibus suis; one clause in particular is said to have been ordained “in civitate Claudia,” which may suggest that the law in question had been decreed in one of the Midwinter Councils at Gloucester. But of one thing only we can be sure, whatever functions the Council may have fulfilled, the king’s will was the motive force which under lay all its action.

In later times, the chief justiciar appears as the normal president of the Council, but in William’s reign it is hard to find any single officer bearing that title. No doubt, when William was in England he himself presided over his council; when he was in Normandy, if the council met at all, which is unlikely, his place would probably be taken by the representative he had left behind him. It is, perhaps, impossible to give a dated list of the vicegerents who appear in William’s reign; our notices of them are very scanty. We have seen that in 1067 William Fitz Osbern and Odo of Bayeux were left as “regents” of England when William made his first visit to Normandy after the Conquest; there has survived an interesting writ of that year in which “Willelm cyng and Willelm eorl” address jointly the country 416magnates of Somersetshire.[298] At the time of the revolt of the three earls in 1075, it is clear that Lanfranc was the king’s vicegerent, an office which he probably filled again during William’s last continental visit in 1086–7. For several reasons it is probable that Odo of Bayeux was regent not long before his fall in 1082; it was as the king’s representative that he took drastic vengeance on the murderers of Bishop Walcher of Durham in 1080, and a most suggestive story in the Abingdon Chartulary shows us King William repudiating the judgment which his brother had given in a local lawsuit during his regency.[299] From the same chartulary we learn that at some time between 1071 and 1081 Queen Matilda herself was hearing pleas at Windsor “in place of the king who was then in Normandy,”[300] though this, of course, need not imply that she was regent in any wider sense of the term. In general, the writs which the king sent from Normandy into England will be addressed directly to the ordinary authorities of the shire; and our knowledge of the succession of William’s representatives is derived from incidental notices elsewhere.

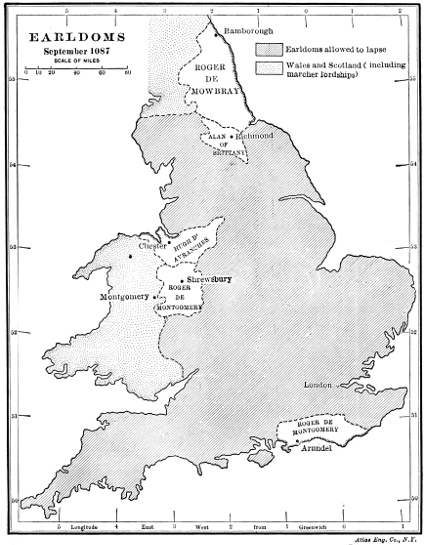

EARLDOMS

September 1087

So far as we can see King William was always attended by a varying number of his barons; a continually changing cortège followed the king in his progress over the country. To this 417fluctuating body, just as to the solemn council, our Latin authorities give the title of the King’s Court, the “Curia Regis,” a phrase which at once connects the amorphous group of William’s courtiers with the specialised executive of Henry II. In a sense, no doubt, William’s court was the only executive of its time, but the employment of these modern terms leads straight towards anachronism; the judicial function of the Curia Regis was quite as important as its executive work, and the court was, after all, only a fraction of that larger council in which we have seen “judicial,” “executive,” and “legislative” powers to be combined. If we are to make for ourselves a distinction between two bodies which are tacitly identified by all early writers, we may say that the Curia Regis was composed of just those members of the Commune Concilium who happened to be in attendance on the king at any given moment. But we must remember that to the men of the eleventh century the king’s “court” and the king’s “council” were one and the same; any distinction between them which we may make exists for our own convenience and nothing more; the court was only a shrunken form of the council.

Even those men who are most frequently to be found in attendance on the king do not seem to be characterised either by special legal knowledge or by definite official position. Great officers of the court, such as the steward and the constable, do repeatedly appear; their positions have not 418yet become annexed to any of the greater baronial houses, and it is probable that their official duties are a reality; but, although Eudo Fitz Hubert (de Rye) the steward, for instance, seems to have been a personal friend of all three Norman kings, and accordingly is a frequent signatory of their writs, such members of the official class seem always to be accompanied by the unofficial barons present. Their attendance also is very intermittent; even the chancellor is much less in evidence in the Conqueror’s charters than in those of Henry I. or II., and under these circumstances we may fairly ask how this unprofessional body acted when required to behave as a court of law. English evidence helps us little, but we get a useful hint as to procedure in certain Norman charters and an analysis of one of them may be quoted:

“At length both parties were summoned before the king’s court, in which there sat many of the nobles of the land of whom Geoffrey, bishop of Coutances, was delegated by the king’s authority as judge of the dispute, with Ranulf the Vicomte, Neel, son of Neel, Robert de Usepont, and many other capable judges who diligently and fully examined the origin of the dispute, and delivered judgment that the mill ought to belong to St. Michael and his monks forever. The most victorious king William approved and confirmed this decision.”[301]

419Geoffrey, bishop of Coutances is one of the more frequent visitors at William’s English courts, and we may suspect that this method was not infrequently used in England when the intricacy of a matter in dispute surpassed the legal competence of the court as a whole. It forms, in fact, the first stage in that segregation of a legal nucleus within the indifferentiated Curia which created the executive organ of the days of the two great Henrys. The early part of this process takes place almost wholly in the dark so far as England is concerned, and we must seriously doubt whether it had led to any very definite results when the Conqueror died; for it is to Henry I., rather than to his father, that we should assign the formation of an organised body of royal administrators. In this, as in other institutional matters, the Conqueror’s reign was a time of tentative expedients and simple solutions; it is essentially a period of origins.

The king’s court is a very mobile body. The king is always travelling from place to place, and where he is at any moment there is his court held also. It is possible to construct an itinerary of our kings from Henry II. onward, but this cannot be done in the case of William, for it is exceptional for his charters to contain any dating clause. William is indeed to be seen issuing writs in very different parts of his kingdom: at Winchester, the ancient capital of Wessex, and York, the ancient capital of Northumbria; at hunting 420seats such as Brill and Woodstock; at Downton in Wiltshire, Droitwich, and Burton-on-Trent; but the list of places which we know to have been visited by William and his court in time of peace is very small compared with the materials which we possess for an itinerary of Henry I., or even of William Rufus. To this deficiency of information is largely to be attributed the fact that, compared with Henry I., William is rarely[302] to be found in the northern parts of his kingdom; it is probable that fuller knowledge of the details of his progresses would reveal a number of unrecorded visits to the shires beyond Watling Street.

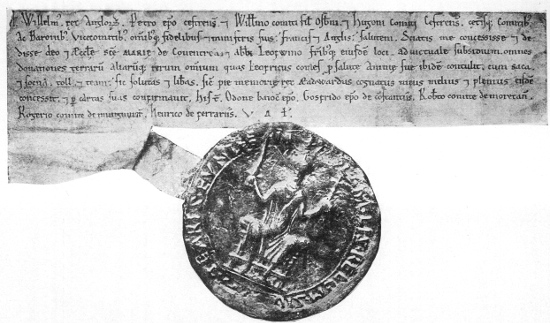

WILLIAM’S WRIT TO COVENTRY

A natural means of transition from the king’s court to the local divisions of the country, the shires and hundreds, is afforded by the recognised means of communication between the two, those writs of which mention has already been made. In form a writ is simply a letter addressed to the persons who are responsible for the fulfilment of its directions, and it is usually witnessed, as we have seen, by a greater or less number of the persons present with the king at the time of its issue. Such a letter might be written either in Latin or in Old English, the former of course being more usual under the Norman kings, and it was usually authenticated with the king’s great seal. This simple device seems to have been the legal means by which the great transfer of land which followed the Conquest was brought 421about; the king would send down one of these writs to the sheriff of a county directing him to put a certain baron in possession of certain specified lands, and the sheriff would need no further warrant. We may give the following as an example of a writ in its Latin form:

“William king of the English salutes Baldwin sheriff of Devonshire and all his barons and servants in that shire.

Know ye that I have granted to my monks of Battle [de Bello] the church of St. Olaf in Exeter with the lands of Shireford and with all other lands and possessions belonging to the said church. Wherefore, I will and command that they hold it freely and in peace and quit from every duty of earthly service and from all pleas and claims and [attendance at] shire and hundred courts and from every geld and ‘scot’ and aid and gift and danegeld and army service, with sake and soke and infangenethef; [quit moreover from] all works on castles and bridges, as befits my demesne alms. Witnessed by Thomas, Archbishop of York, and William, the son of Osbert at Winchester.”[303]

Any comment on the privileges conveyed by the document would be outside our present purpose, which is merely to illustrate the way in which King William sent his instructions into the different parts of his kingdom. But the formula of address deserves notice because it suggests that the writ was really directed to the shire 422court where the sheriff and the “barons and king’s servants” of the shire periodically met. There it would be read in the presence of the assembled men of the county, and the sheriff would forthwith proceed to carry its directions into effect. The sheriff in the king’s eyes is clearly the executive officer of the shire and his importance is not to be measured by the modern associations aroused by his title. The Latin word which we translate as “sheriff” is vicecomes and this word also represents the French vicomte, a fact which should by no means be ignored, for the sheriffs of the half-century succeeding the Conquest resemble their French contemporaries much more closely than either their English successors of the twelfth century or the shire reeves of the Anglo-Saxon period. For one thing, they are in a sense true vicecomites: the sheriff was the chief officer in each county in which there was no earl, and the earldoms created by William were few, and with the exception of Kent were situated in remote parts of the land. Then also it is certain that some at least of the more important sheriffdoms were hereditary in much the same sense as that in which the great earldoms before the Conquest were hereditary—the cases of Devon, Wiltshire and Essex are examples—to which we must add that the early Norman sheriffs are often very great men. Baldwin the sheriff of Devon was the son of William’s own guardian, Count Gilbert of Brionne, and two of his sons 423followed him in the office. Edward the sheriff of Wiltshire was the ancestor of the medieval earls of Salisbury. Urse de Abetot, alternately despoiler and tenant of the church of Worcester was the chief lay landowner in Worcestershire, Hugh Fitz Baldric, sheriff of Yorkshire, was among the greater tenants in chief in that county. In local, as in general constitutional history, it is most important not to read the ideas of Henry II.’s time into the institutions which prevailed under the Conqueror. Had William in 1070 tried to carry out a general deposition of his sheriffs, such as Henry II. actually achieved in 1170, the attempt, we may be sure, would have led to a revolt, and the mass of the baronage would have sided with the official members of their class. But indeed, so long as the Normans were still intruders in a conquered country, it was only politic on William’s part to govern through men of strong territorial position, men who had the power to enforce the king’s commands in their own localities. In the choice of his local administrators, as in certain other aspects of his policy, William was preparing difficulties for his successors, but his justification lay in the essential needs of his own time. The great transfer of land from Englishmen to Normans, to take one instance, could never have been accomplished if the local government of the country had been in weak hands.

In the period immediately following the Conquest, 424the four years between 1066 and 1070, which in so many respects are distinct from the rest of William’s reign, perhaps the majority of the sheriffdoms continued to be held by Englishmen. Within this period writs are addressed to Edmund, sheriff of Herefordshire, Sawold of Oxfordshire, Swegen of Essex, and Tofig of Somerset, and even after 1070 such Englishmen as Ethelwine, sheriff of Staffordshire,[304] continue the series. In fact, the development of the provincial administration in this respect seems to have followed a very similar course to that which we have noted in the case of the king’s court; there is a period in which men of both races are mingled in the government of the shires, as well as in attendance on the king’s person. But by the end of the reign the change in both respects had become almost complete, and the introduction of Norman sheriffs began early; for before 1069 Urse de Abetot had already entered upon his aggressiveaggressive course as sheriff of Worcestershire, and it is very probable that even by the time of William’s coronation the Norman Geoffrey had succeeded Ansgar the Staller in his sheriffdom of London and Middlesex.[305]

From the sheriffs we may pass naturally to their superiors in rank, the earls. Taught by experience, William regarded the vast, half-independent earldoms of the later Anglo-Saxon period with profound mistrust, and as the occasion 425presented itself he allowed them to lapse. All the earldoms held by members of the house of Godwine became extinct with the battle of Hastings, but the great provincial governments of Mercia and Northumbria probably lasted until the final revolt of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the spring of 1069. After their suppression there remained three minor earldoms of Anglo-Saxon origin, East Anglia, Northampton, and Bernicia, the holders of which, as we have seen, were mainly responsible for the rebellion of 1075. Upon William’s triumph in the latter year the East Anglian earldom was suppressed, that of Northampton ceases to exist for the remainder of the Conqueror’s reign, and we have already noticed the reasons which led to the continuance of the earldom of Bernicia. Similar motives led to the creation of the four earldoms which alone can be proved to have come into being before 1087, and which deserve to be considered in detail here. They are:

1. Hereford, granted to William Fitz Osbern before January, 1067.

2. Shrewsbury, granted to Roger de Montgomery circ. 1070.

3. Chester, granted to Hugh d’Avranches, before January, 1071.

4. Kent, granted to Odo, bishop of Bayeux, possibly before January, 1067.

The exact extent of the earldom of Hereford is doubtful, for there exists a certain amount of 426evidence which makes it probable that William Fitz Osbern possessed the rights of an earl over Gloucestershire and Worcestershire in addition to the county from which he took his title. We have already discussed the general significance of the early writ which the king addressed to Earl William and the magnates of Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, and the evidence of this document is supported by the fact that the earl appears as dealing in a very arbitrary fashion with land and property in both shires.[306] It is probable on other grounds that Gloucestershire lay within the Fitz Osbern earldom, for William’s possessions extended far south of the Herefordshire border to the lands between Wye and Usk in the modern county of Monmouth, and the addition of Gloucestershire to Herefordshire is required to complete the line of earldoms which lay along the Welsh border. On the other hand it seems probable that Worcestershire never belonged to Roger, William Fitz Osbern’s son, for in 1075 it was the main object of the royal captains in the west to prevent him from crossing the Severn to the assistance of his friends in the midlands. In any case the early date at which the earldom of Hereford was created deserves notice, for it shows that within four months of the battle of Hastings William was strong enough to place a foreign earl in command of a remote 427and turbulent border shire. Short as was his tenure of his earldom William Fitz Osbern was able to leave his mark there; fifty years after his death there still remained in force an ordinance which he had decreed to the effect that no knight should be condemned to pay more than seven shillings for any offence.[307] Lastly, it should be noted that in a document of 1067[308] William Fitz Osbern is styled “consul palatinus,” a title which should not be construed “palatine earl,” but which rather means that William, though raised to comital rank, still retained the position of “dapifer” or steward of the court, which he inherited from his father, the unlucky Osbern of the Conqueror’s minority, and in virtue of which the earl of Hereford continued to be the titular head of the royal household.

To the north of William Fitz Osbern, Roger de Montgomery, the other friend of William’s early days, was established in an earldom threaded by the Severn as Herefordshire is threaded by the Wye, and stretching along the former river to the town and castle to which the house of Montgomery left its name. From the standpoint of frontier strategy Roger’s position was even more important than that held by his neighbour of Hereford; for Shrewsbury, the point where roads from London, Stafford and the east, and Chester and the north met before crossing the 428Severn, continued throughout the Middle Ages to be the key to mid-Wales. Unfortunately, the date at which Roger received the Shropshire earldom cannot be fixed with certainty, for, while he appears at court in the enjoyment of comital rank as early as 1069, the one account which we possess of the operations at Shrewsbury in the latter year virtually implies that the town was then in the king’s hand. Probably the discrepancy is to be explained by the fact that before he received his grant of Shropshire Roger had been given the castle of Arundel and the town of Chichester in the distant shire of Sussex.[309] It is highly probable, in fact, that Roger possessed the rights of an earl over the latter county,[310] and such a grant would fall in well with the general policy of the Conqueror, for Sussex was only less important than Kent as a point of arrival from the continent, and in the eleventh century Arundel was a port. Most probably Roger was appointed earl of Shrewsbury after the events of 1069 had shown that a coalition of Welsh and English was the most pressing danger of the moment, but he continued in possession of Arundel and Chichester.[311] Once established at Shrewsbury, Roger and his followers speedily proceeded to take the offensive against the Welsh, and in 1072 Hugh de Montgomery, the earl’s eldest son, extended his 429raids as far south as Cardigan. In addition to being the earl of two English shires, Roger de Montgomery held great possessions in Normandy and France; in right of his wife he was count of Bellême, and by a more distant succession he became Seigneur of Alençon, while a series of marriage alliances placed him at the head of a powerful group of kinsmen. But it is probable that the place which he holds in history is due less to his wide lands and great power than to the accident that one of his knights became the father of the greatest historian whom Normandy had so far produced. The earl of Shrewsbury was a great baron and a loyal knight, but when we regard him as representing the best aspect of the Norman conquerors of England we are, consciously or otherwise, guided by the place which he fills in the narrative of the chronicler born within his earldom, Ordericus Vitalis.

The circumstances under which the earldom of Chester was created present a certain amount of difficulty. Chester itself was the last great town of England which called for separate reduction at William’s hands, and it did not fall until the beginning of 1070. Then we are told that William gave the earldom of Cheshire to Gherbod, one of his Flemish[312] followers, but an original charter[313] of the time shows us Hugh Lupus of Avranches already addressed as earl of Chester in or before February, 4301071. Now Gherbod (who never appears in any English document) was killed in Flanders in the latter month, so that we can only suppose that, if he ever received the earldom, he never took practical possession of it, and resigned it almost immediately. The historical earldom of Chester is that which remained in the family of Hugh of Avranches for two centuries and formed the “county palatine” which survived until 1536. It was a frontier earldom in a double sense: Chester controlled the passage of the Dee into North Wales and also the coast road to Rhuddlan and Anglesey, while so long as all England north of Morecambe Bay was Scotch territory, it was politic to entrust much power to the man who commanded the west coast route from the midlands to the north. Judging from the evidence of Domesday Book, the whole of Cheshire formed one compact fief in the hands of its earl; it is the only county in England possessed outright by one tenant-in-chief. Of Earl Hugh, we can draw the outlines of no very pleasing picture. He was devoted to every kind of sensual indulgence, and so fat that no horse could carry him; he is charged like most of his contemporaries with disrespect to the rights of church property. On the other hand, he was, so far as we can see, unswervingly faithful to the king, and he abundantly fulfilled his natural duty of keeping the Welsh away from the English border; nor is it probable that William would have entrusted to a lethargic 431fool one of the most responsible positions in his kingdom.

The case of Kent stands apart from that of its three sister earldoms. The latter were created as the readiest means of securing a part of the country remote from the centre of authority. The importance of Kent lay in its position between London and the Channel ports. Through the county ran the great Dover road, the main artery of communication between all northern England and the continent, the obvious line along which an invader would strike at London. The rising of 1067 proved the reality of such danger and it was reasonable that the county should be placed in charge of the man who by relationship was the natural vicegerent of the king when the latter was across the Channel. Territorially, Kent was much less completely in the hands of its earl than was the case with either of the three western earldoms, but the possessions of Odo of Bayeux in the rest of England placed him in the first rank of landowners. The date at which the earldom was created is not quite certain; like William Fitz Osbern, Odo may have received his earldom at the time of his joint regency with the former in 1067. He is addressed as bishop of Bayeux and earl of Kent in a charter which is not later than 1077, and his rank as an earl is strikingly brought out in the circumstances of his dramatic arrest in 1082.

Judged by later events, the creation of these four great earldoms may seem to have been a mistake 432on the part of the Conqueror. Hereford, Kent, and Shropshire in turn served as the base of operations for a formidable revolt within fifty years of the Conquest. Their formation also contrasts with the general principles which governed the distribution of land among the Norman baronage, principles which aimed in the main at reproducing the discrete character of the greater old English estates. Before the Conquest no such compact block of territory as the earldom of Cheshire had ever been given in direct possession to any subject. But here, as in the case of the powerful sheriffdoms of William’s time, his justification lay in his immediate necessities. His reason for the creation of the western earldoms was the same as that which prompted his successors to entrust almost unlimited power to the great lords on the march of Wales. It was absolutely necessary to secure central England against all danger from Welsh invasion, and the king himself had neither the time nor the means to conquer Wales outright. He found a temporary solution by placing on the debatable border three earls, strong enough in land and men to keep the Welsh at bay and impelled by self-interest to carry out his wishes. And also we should remember that it was only wise to guard against a repetition of that combination of independent Welsh and irreconcilable English which had been planned in 1068; the three western earldoms were all created before the capture of Ely in 1071 ended the series of 433national risings against the Conqueror. Lastly, it will not escape notice that at the outset all four earldoms were given to men whom William knew well and had every reason to trust. Odo of Kent was his half-brother; Roger de Montgomery and William Fitz Osbern were young men already at his side in his early warfare before Domfront; Hugh of Chester belonged to a family which had held household positions in his Norman court. William might well have felt that he could not entrust his delegated power to safer hands than these.

Four or five shires only were placed under the control of separate earls, and in them as elsewhere in England the old English system of local government continued with but little change. The shire and hundred courts continued to meet to transact the judicial and administrative business of their respective districts though the manorial courts which sprang up in great numbers as a result of the Conquest were continually withdrawing more and more of this work. We know very little of the ordinary procedure of the local courts; it is only when they take part in some especially important affair such as the Domesday Inquest that the details of their action are recorded. An excellent illustration of the way in which the machinery of the shire court was applied to the settlement of legal disputes is afforded by the following record, taken from the history of the church of Rochester:

“In the time of William the Great, king of the English, father of William, also king of that nation, there arose a dispute between Gundulf, bishop of Rochester, and Picot, sheriff of Cambridge, about certain land, situated in Freckenham, but belonging to Isleham, which one of the king’s sergeants, called Olchete, had presumed to occupy in virtue of the sheriff’s grant. For the sheriff said that the land in question was the king’s, but the bishop declared that it belonged to the church of St. Andrew. And so they came before the king who ordered that all the men of that shire should be brought together, that by their verdict [judicio], it might be determined to whom the land should rightly belong. Now they, when assembled, through fear of the sheriff, declared the land to belong to the king, rather than to Blessed Andrew, but the bishop of Bayeux, who was presiding over the plea, did not believe them, and directed that if they were sure that their verdict was true, they should choose twelve out of their number to confirm with an oath what all had said. But when the twelve had withdrawn to consider the matter, they were struck with terror by a message from the sheriff and so, on returning, they swore that to be true which had been declared before. Now, these men were Edward of Chippenham, Heruld and Leofwine ‘saca’ of Exning, Eadric of Isleham, Wulfwine of Landwade, Ordmer of Bellingham, and six others of the better men of the county. After all this, the land remained in the king’s hand. But in that same year a certain monk, called Grim came to the bishop like a messenger from God, for when he heard what the Cambridge men had sworn, he was amazed, and in his wrath called them all liars. For this monk had formerly been the reeve of Freckenham, and had 435received services and customary payments from the land in question as from the other lands belonging there, while he had had under him in that manor one of the very men who had made the sworn confirmation. When the bishop of Rochester had heard this, he went to the bishop of Bayeux and told him the monk’s story in order. Then the bishop of Bayeux summoned the monk before himself and heard the same tale from him, after which he summoned one of those who had sworn, who instantly fell down before his feet and acknowledged himself to be a liar. Then again he summoned the man who had sworn first of all, and on being questioned he likewise confessed his perjury. Lastly, he ordered the sheriff to send the remaining jurors to London to appear before him together with twelve others of the better men of the county to confirm the oath of the former twelve. To the same place also, he summoned many of the greater barons of England, and when all were assembled in London, judgment was given both by French and English that all the jurors were perjured since the man after whom all had sworn had owned himself to be a liar. After a condemnation of this kind the bishop of Rochester kept the land, as was just, but since the second twelve jurors wished to assert that they did not agree with those who had first sworn, the bishop of Bayeux said that they should prove this by the ordeal of iron. They promised to do so, but failed, and by the judgment of the other men of their county they paid three hundred pounds to the king.”[314]

In this extract we get a vivid picture of the way in which the two systems of government, Norman 436and English, worked in conjunction. In the above transactions the matter in dispute is referred for settlement to the ancient shire court of Cambridgeshire, and determined by the oaths of English jurors, but the procedure is a Norman innovation, and it is the Conqueror’s brother who presides over the plea. The terror inspired by the sheriff is an eloquent commentary on the vague complaints of the chroniclers concerning the oppression of the king’s officers, and we may welcome this casual glimpse into the relations between the English folk of the county and the formidable president of their court. But the remaining details of the story may well be left to explain themselves.

But a suit of this kind must not be taken as typical of the ordinary work of the shire court; it was not every day that it had to discuss the affairs of a king and a bishop. It was the exceptional rank of the parties concerned in this instance which enabled them to traverse the original judgment of the shire court and to employ a procedure quite alien to the methods of the Old English local moots. So far as we can see, the practice of settling disputes by the verdict of a small body of sworn jurors was entirely a Norman innovation, and we may be sure that it would not have been employed in this case if the veracity of the men of the shire had not been called in question. Within ten years of the date of our story the king’s fiscal rights all over England were to be ascertained by the inquisition of sworn 437juries in the Domesday Inquest, but the employment of this method in ordinary judicial cases continued to be highly exceptional down to the beginning of the Angevin period, and our instance may perhaps claim to be the first recorded example of its use. The duty of the shire court in all pleas of the kind, to which it would have been confined in all probability in the above case if the king had not been attracted within the dispute, was simply to declare the customary law which related to the matter in hand. In principle, a judgment of this kind is entirely different from the verdict on oath given by men selected for their local knowledge as were the jurors in our story: if carried out honestly the result would be the same in either case—the land would be assigned to the proper person; but whereas this would only follow incidentally if inevitably from the unsworn judgment of the court as a whole, the sworn verdict would consist of an actual award. The latter principle produced the Angevin juries of presentment; the former principle continued to underlie the action of the shire and hundred courts so long as they exercised judicial functions. The interest of the Isleham case above lies in its transitional character: it shows us the sworn jury used as a secondary resort after the accustomed practice of the shire court had failed to give satisfaction; already in 1077 it is available for the amendment of wrongs arising “pro defectu recti,” on the part of the domesmen of the local assemblies.

438But just as the introduction of the jury was bringing a new procedure into competition with the antiquated methods of the local courts, so a quite different set of causes was cutting at the root of their influence. Centuries before the Conquest considerable powers of jurisdiction had been placed in private, generally ecclesiastical, hands, but the gradual extension of the sphere of private justice, until it became an integral part of the whole manorial organisation, was due to the feudal principles which triumphed in 1066. Private jurisdiction, as it existed in the Conqueror’s day, represents the blending of at least three distinct principles. In the first place, the king can confer jurisdictional rights on whomsoever he pleases; from this point of view a private court will represent a portion of royal power in the hands of a subject. But in the second place, the king himself is only the first of a number of men who possess these rights in virtue of their rank; it is probable that the political theory of the eleventh century would allow that a great man was naturally possessed of such powers of justice as were appropriate to his personal status, though it would be unable to give a rational explanation of the fact. And then even in the Conqueror’s time there can be traced the idea, the prevalence of which was destined to cover England with manorial courts, that the tenurial relation between a lord and his tenant gave the former jurisdictional powers over the latter; that, independently 439of a royal grant, or of his personal rank, a lord was entitled to hold a court for his “men”; that the economic relation between landlord and tenant produced a corresponding tie in the sphere of jurisdiction. It is the first two of these principles which produced the “sake and soke” of Anglo-Saxon law, it is the last which explains the extension of manorial justice in the century following the Conquest.[315] It is worth while making this classification, for it reveals one of the main lines of divergence between English and French law in the Middle Ages. That which in England was the least persistent of our three principles, the element of personal rank, became in France the basis of the famous classification of jurisdictional powers into “haut, moyen, et bas justice,” which endured until the Revolution, and the main reason for this difference lies in the circumstances of the Norman Conquest. By that event, whatever the explanation of private justice which may have passed current among those who troubled themselves about such matters, all such powers proceeded directly or indirectly from the king; directly when the Conqueror made an explicit grant of “sake and soke” to a baron, indirectly if the latter claimed his court as proceeding from his tenure of his land, for the land itself was held of the king who had granted it to him. Here then, in the Sphere of local justice, we see the union of Norman and English ideas; the 440judicial power which results from the facts of tenure is added to the judicial power which is exercised in virtue of the king’s grant.

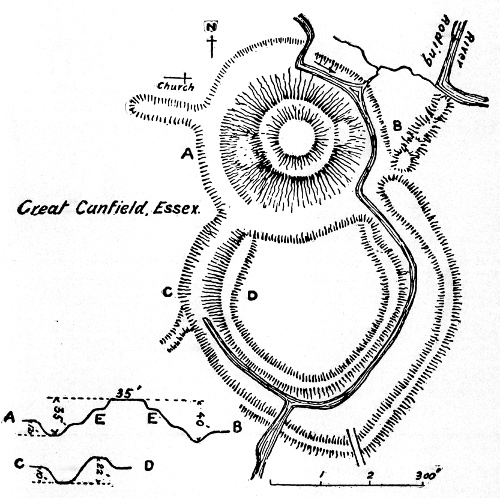

PLAN OF GREAT CANFIELD CASTLE, ESSEX

It should not be thought that the Norman barons, in their seats across the Channel, had exercised jurisdictional powers in advance of those possessed by the English nobles and thegns whom they were destined to displace. The fact that the grants of private justice which the Conqueror made to his followers in England were set forth in the same conventional phrases as Edward the Confessor would have employed in like case, may be set down to William’s desire to preserve the forms of Old English law; but there is no doubt that the Norman barons were quite content to accept the Anglo-Saxon formulas as a satisfactory expression of the jurisdictional powers which they were to enjoy. In fact, the latter were ample enough. Thus, when the Conqueror confirmed his “customs” to the abbot of Ely, these included “sake and soke, toll and team and infangenethef, hamsocne and grithbrice, fihtwite and fyrdwite within boroughs and without, and the penalties for all other crimes which are emendable on his land and over his men, as he held them on the day when King Edward was alive and dead.”[316] Terms like these cover nearly the whole field of “civil and criminal justice.” Sake and soke may be construed as the right to hold a court; toll explains itself; “team” implies that persons might be 441“vouched to warranty” in the court, a process which is too technical to be explained here, but the grant of which made a court capable of entertaining suits arising out of the transfer of land; “infangenethef”“infangenethef” is the right of trying and executing thieves taken on one’s land; “hamsocne” (or rather “hamfare”) is the breach of a man’s house; “grithbrice” is the violation of the grantees’ special peace; “fihtwite” is the fine for a general breach of the peace; “fyrdwite” is the fine for failure to appear in the national militia, the fyrd. Privileges like these, within the area to which they are applicable, empower the grantees’ court to take cognisance of all crimes and misdemeanours which might be expected to occur in the ordinary course of events; the Isle of Ely and some dozens of external manors were practically withdrawn altogether from the national system of justice. We have no reason to suppose that the average baron in Normandy was endowed with anything like these powers, nor need we suppose that grants of such wide application were very frequently made to the conquerors of England; but when, two years after the date of Domesday Book, we find Roger de Busli—a great baron certainlycertainly, but not belonging absolutely to the first rank—granting to his monks of Blyth “sac and soke, tol and team and infangenethef, iron and ditch and gallows with all other privileges [libertates] which I formerly held of the king,”[317] we can 442see that the feudalisation of justice had gone far by the time of King William’s death.

We may then fairly inquire what was the relation which these new manorial courts bore to the old national courts which they were destined to supplant. With reference to the hundred and shire assemblies, the answer is fairly simple: the two systems of jurisdiction were concurrent. The hundred court, we must remember, was in no sense inferior to the shire court, and in the same way the manorial court was in no sense inferior to either of these bodies; it rested with the individual litigant before which of them he should bring his plea, with this most important exception—that the lord of the party impleaded could if he wished “claim his court,” and so appropriate the profits of the trial. Here was a most powerful force steadily drawing business away from the shires and hundreds, and attracting it within the purview of the manor. But then the wishes of the peasantry told in the same direction: the manorial court was close at hand; it was composed of neighbours who knew each others’ concerns, and were constantly associated in the common agricultural work of the vill; it gratified the tendencies towards local isolation, which were pre-eminently strong in the early Middle Ages. The manorial court supplied justice at home, and we should remember how many hindrances beset recourse to the hundreds and shires. In all Staffordshire there were only five hundreds; in all Leicestershire only four wapentakes; the 443prosecution of a suit in any of these courts must have meant grievous weariness and loss, the establishment of a manorial court must have meant an immediate alleviation of the law’s delay. He would have been an exceptionally far-sighted villein who in 1086 could foresee that the convenient local court would eventually be the agent by which his descendants would be thrown into dependence on the will of the lord, with no other protection than the traditional and unwritten “custom of the manor”; that the establishment of the lord’s justice would ultimately exclude all reference to the more independent if more antiquated justice of the men of the hundred of the shire, on the part of the lesser folk of his vill.

One question connected with the rise of manorial courts deserves attention here—did they displace any court proper to the vill as a whole, independently of its manorial aspect? It is clear that every now and again the men of the vill must have met, if only to regulate the details of its open-field husbandry. But whether such a meeting had any formal constitution or judicial functions—whether, that is, it was a “township-moot,” in the accepted sense of the words[318]—is excessively doubtful. The fact that we hear nothing definitely about it in the documents of the Anglo-Saxon period is not quite conclusive 444against its existence; it is more to the point that the hundred moot seems to be the lowest stage reached by the descending series of national courts. It is probable, therefore, that the ordinary township never possessed any court other than that which belonged to it in its manorial aspect.

We have seen enough to know that the jurisdictional and economic aspects of feudalism were intimately connected: the manorial court was the normal complement of the average manor. No less closely associated in practice were the military and tenurial elements of the feudal system, and upon a superficial view of this system it is these latter elements which rise into greatest prominence. Nor is this altogether unjust, for, although it is not probable that any change induced by the Norman Conquest so profoundly affected English social life as did the universal establishment of private jurisdiction, yet the introduction of military tenures, and the creation of a feudal army rooted in the soil of England, are phenomena of the first importance, and the form which they assumed in the course of the next century was due in essence to the personal action of the Conqueror himself, and to the political necessities of his position.

The rapidity with which England had been conquered had demonstrated clearly enough the inefficiency of the Anglo-Saxon military system, and the changes introduced in this matter by King William were revolutionary, both in details and in principle. The military force at the disposal 445of Edward the Confessor had consisted of two parts: first, the fyrd or native militia, based on the primitive liability of every free man to serve for the defence of his county, and secondly a body of housecarles, professional men-at-arms, who served for pay and were therefore under better discipline and available for longer periods of service than the rustic soldiery of the shires. There is no good evidence to prove that the Anglo-Saxon thegn was burdened with any military obligation other than that which rested on him as a free man, but there are certain passages which suggest that, in the latter days of the old English state, the king in practice would only call out one man from each five hides of land, and that he would hold his more powerful subjects responsible for the due appearance of their dependants. If this were an attempt to create a small but efficient host out of the great body of the fyrd, it came too late to save the situation and, so far as our evidence goes, it was the professional housecarles who bore the brunt of the great battles of 1066. By derivation at least the housecarle must have been a man who dwelt in his lord’s house as a personal retainer; and, although we know that men of this class had received grants of land from the last native kings, there is no reason to believe that their holdings were conditional on their services, or indeed that they were other than personal marks of favour, quite unconnected with the military duty of the recipient.

446The essential features of the Norman system were entirely different to this. Each tenant in chief of the crown, as the condition on which he held his lands, was required to maintain, equip, and hold ready for immediate service a definite number of knights, and the extent of his liability in this matter was not, save in the roughest sense, proportional to his territorial position, but was determined solely by the will of the king. Transactions of this kind most probably took place at the moment when each tenant in chief was put into possession of his fief, and their observance on the part of the grantee was guaranteed by the penalty of total forfeiture in the event of his appearance at the king’s muster with less than his full complement of knights. His military liability once ascertained, a tenant would commonly proceed to enfeof some of his knights on portions of his estate, keeping the remainder in attendance on his person. As time went on the number of landless knights continually became less and less, and by the end of the Conqueror’s reign, the greater part of every fief was divided into knight’s fees, whose holders were bound by the circumstances of their tenure to serve with their lord in the discharge of the military service which he owed the crown. No definite quantity of land, measured either by assessment or value, constituted the knight’s fee; but, judging from the evidence of a later period, it seems certain that each tenant in chief was burdened with the service 447of a round number of knights, twenty, thirty, or the like, and it is quite possible that these round figures were influenced by the Norman constabularia of ten knights, a military unit which we know to have prevailed across the Channel before the conquest of England.[319]

But the work of subinfeudation once started, no limit in theory or practice was ever set to it in England, and in the earliest period of Norman rule we find knights, who held of a tenant-in-chief, subletting part of their land to other knights and the latter continuing the process at their own pleasure. In Leicestershire, for example, the vill of Lubbenham was held of the king by the archbishop of York, and had been let by him to a certain Walchelin, who had enfeoffed with it a man of his own called Robert, who had granted three carucates of land in the manor to an unnamed knight as his tenant. But this is an exceptional case, for it is unusual for Domesday to reveal more than two lords in ascending order between the peasant and the king. A process of the same kind had not been unknown in England in the time of King Edward; churches had been leasing land to their thegns; and thegns, whom a Norman lawyer would consider to hold of the king, had been capable of subletting their estates to their dependants. But the legal principles which underlay 448dependant land tenure had never been worked out in England, as they had been elaborated in Normandy before the Conquest, and in two important respects at least there was a marked difference between the old and the new system. On the one hand it is extremely doubtful whether Anglo-Saxon law had developed the idea that all land, not in the king’s immediate possession, was held directly or indirectly of the crown; and in the second place the old English system of land tenure was far slacker and less coherent than its Norman rival. Domesday Book contains frequent references to men who could leave one lord and seek another at will, and this want of stability in what was perhaps the most important division of private law meant a corresponding weakness in the whole of the Anglo-Saxon body politic. Here as elsewhere the Norman work made for cohesion, permanence, and theoretical consistency.

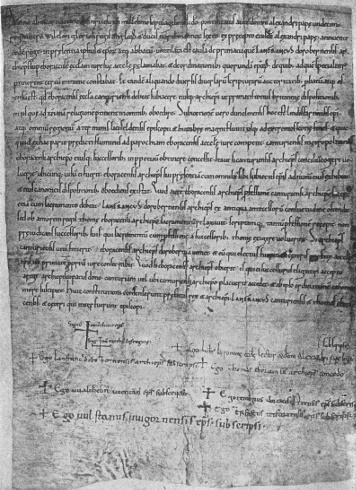

AUTOGRAPH SIGNATURES TO WINDSOR AGREEMENT

It was also an innovation upon accepted practice that the Conqueror extended to ecclesiastical estates the military responsibilities which he imposed upon lay fiefs. Long before the Confessor’s time, the churches had been subletting land to their thegns on condition that the latter should do the military service which the said churches owed to the king; but the duty in question merely represented the amount of fyrd service due from the lands of each religious house, and was in no sense the result of any bargain between the king and the latter. On the other hand, the number 449of knights maintained by an ecclesiastical tenant of King William depended in the last resort upon the terms which that tenant, whether bishop or monastery, had made with the new sovereign. The Conqueror could not venture to dispossess a native religious house as he could dispossess a native thegn or earl; but he could insist that such a body should make its contribution towards the new army which he was planting on the soil of England, and he could determine the minimum amount of the contribution in each case. So far as our evidence goes, the knight service demanded from a monastery was fixed in a much more arbitrary manner than that imposed on a lay tenant; a baron’s military liabilities would greatly correspond in the main, though very roughly, with the extent of his fief, but no principle of the kind can have been applied to the burden laid upon the church lands. The abbeys of Peterborough and Abingdon were bound to supply sixty and thirty knights respectively, but St. Albans escaped with a servitum debitum of six, and St. Benet of Hulme was only debited with three. It is more than probable that political conditions went far towards producing these violent discrepancies; a monastery, like Peterborough, which had displayed strong nationalist tendencies, might fairly enough be penalised by the imposition of a heavy burden of service towards the maintenance of the foreign rule. On the other hand, the process in question was regarded in a very different 450light by the Norman abbots who were gradually introduced in the course of the reign, and by the English monks placed under their government. To the former the creation of knights’ fees meant a golden opportunity of providing for their necessitous kinsmen beyond the Channel; to the latter the withdrawal of land from the immediate purposes of the church forboded an ultimate shrinkage in the daily supply of beef and beer. The local chronicler of Abingdon abbey tells us sorrowfully how Abbot Ethelhelm sent over into Normandy for his kinsmen, and invested them with the possessions of the monastery to such an extent that in one year he granted seventy manors to them, which were still lacking to the church a hundred years later.

Reference should perhaps be made here to the difficult question of the actual numbers of the territorial army which rose at King William’s bidding upon the conquered land. In a matter of this kind the statements of professed chroniclers must be wholly ignored; they represent mere guesswork, and show a total insensibility to the military and geographical possibilities of the case. Several attempts, based upon the safer evidence of records, have recently been made to estimate the total number of knights whom the king had the right to summon to his banners at any given moment, and it is probable that the results of such inquiries represent a sufficiently close approximation to the truth of the matter. On the 451whole, then, we may say that the total knight service of England was fixed at something near five thousand knights, of whom 784 have been assigned to religious tenants-in-chief, 3534 have been set down as the contribution of lay barons, the remainder representing the allowance properly to be made for the deficiencies in our sources of information.[320] The question is important, not only for the influence which tenure by knight service exercised on the later English land-law, but also for its bearing upon the cognate problem of the numbers engaged in the battle of Hastings, which has already received discussion here.

From knight service we may pass naturally enough to the kindred duty of castle-guard. The castles which had arisen in England by the time of the Conqueror’s death belong to one or other of two great classes. On the one hand, there was the royal fortress, regarded as an element in the system of national defence, whether against foreign invasion or native revolt; to the second class belong the castles which were merely the private residence of their lord. In castles of the former class, which were mostly situated in boroughs and along the greater roadways, the governor was merely the king’s lieutenant; Henry de Beaumont and William Peverel were 452placed in command of the castles of Warwick and Nottingham respectively, in order that they might hold those towns on the king’s behalf. This being the case, it was only natural that garrison duty as well as service in the field should be demanded from the knights whom the barons of the neighbourhood were required to supply; the knights of the abbot of Abingdon were required to go on guard at Windsor Castle. Of the seventy castles which we may reasonably assume to have existed in 1087, twenty-four belong to this class, and twenty of the latter are situated in some borough or other, and this close connection of borough and royal castle is something more than a fortuitous circumstance. In Anglo-Saxon times, it is well ascertained that each normal borough had been the military centre of the district in which it lay, and had in fact been the natural base of operations in the work of local defence. The Normans brought with them new ideas on the subject of defensive strategy, but the geographical and economic conditions which gave to the boroughs their military importance in early times were not annulled by the Norman Conquest; and it would still have been desirable to safeguard the growing centres of trade from external attacks, even if it had not been expedient in Norman eyes to set a curb upon the national spirit among the dwellers in the English towns. No general rule can be laid down as to the custody of these royal castles; it was not infrequent for 453them to be held on the king’s behalf by the sheriff of the shire in which they might be situated, but the Conqueror would entrust his fortress to any noble of sufficient military skill and loyalty, and, as in the cases of Warwick and Nottingham, a tenure which was originally mere guardianship might pass in the course of time into direct possession.

The larger class of private castles is less important from the institutional standpoint. In Normandy the duke had the right to garrison the castles of his nobility with troops of his own, but the Conqueror does not seem to have extended this principle to England. It is very probable that he would insist on his own consent being given to any projected fortification on the part of his feudatories, but so long as his rule was threatened by English revolt, rather than by Norman disloyalty, he would not be greatly concerned to limit the castle-building tendencies of his followers. On the Welsh border, for example, where the creation of a strong line of castles was an essential part of the business of frontier defence, the work of fortification must largely have been left to the discretion of the earls of Shrewsbury and Chester, and to the enterprise of the first generation of marcher lords. East of a line drawn north and south through Gloucester, lie nearly half of the total number of castles which we can infer to have been built during the Conqueror’s reign, but only fourteen of them were in private hands.

454Underneath all these violent changes in the higher departments of the military art, the old native institution of the fyrd lived on. Two years after Hastings, at the dangerous crisis occasioned by the revolt of Exeter, we find the Conqueror calling out the local militia, and at intervals during his reign the national force continues to be summoned, not only by the king but by his lieutenants, such as Geoffrey of Coutances at the time of the relief of Montacute. It is not necessary to assume that William had prescience of a day when an English levy might be a useful counterbalance to a feudal host in rebellion; he inherited the military as well as the financial and judiciary powers of his kinsman King Edward, and obedience would naturally be paid to his summons by everybody who did not wish to be treated as a rebel on the spot. It does not seem that the Conqueror materially altered the constitution or equipment of the fyrd; in fact he had no need to do this, for its organisation and armament, obsolete as they were in comparison with those of the feudal army, still enabled it to fight with revolted Englishmen or Scotch raiders on more or less of an equality. For the serious business of a campaign the Conqueror would rely on the small but efficient force of knights at his command, and it is to be noted that no barrier of racial prejudice prevented the absorption of Englishmen of sufficient standing into the knightly class. The number of Englishmen who are entered 455in Domesday Book, on a level withwith the Norman tenants of a great baron, is considerable, and it is by no means improbable that, below the surface of our records, a process had been going on which had robbed the heterogeneous militia of King Edward’s day of its wealthier and more efficient elements. Many a thegn who would formerly have joined the muster of his shire with an equipment little, if at all, superior to that of the peasantry of his neighbourhood, will have received his land as the undertenant of some baron, and have learned to adopt the military methods of his Norman fellows. We cannot define with accuracy the stages by which this process did its work, but when the time came for Henry II. to reorganise the local militia, it was with a force of yeomen and burgesses that he had to deal.

We have now given a brief examination to the main departments of administration, military and political, as they existed under the Conqueror. Two general conclusions may perhaps be suggested as a result of our survey. The first is that, throughout the field of government, revolutionary changes in all essential matters have been taking place under a specious continuity of external forms. The second is, that the Conqueror’s work is in no respect final; the shock of his conquest had wrecked the obsolescent organisation of the old English state, but the development of the new order on which his rule was founded was a task reserved for his descendants. 456The Curia Regis, which attended King William as he passed over his dominions, was a body the like of which had not been seen in King Edward’s day, but it was a body very unlike the group of trained administrators who transacted the business of government under the presidency of Henry II. The feudal host in England owed its being to the Conqueror, but no sooner was it firmly seated on the land than the introduction of scutage under Henry I. meant that the king would henceforth only allow the Conqueror’s host to survive in so far as it might subserve the purposes of the royal exchequer. King William’s destructive work had been carried out with unexampled thoroughness, order, and rapidity, but it was inevitable that the process of reconstruction which he began should far outrun the narrow limits of any single life.

Penny of William I.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content