Search london history from Roman times to modern day

Among the famous stories which enliven the history of the early dukes of Normandy there stands out prominently the tale of the romantic circumstances which led to the birth of Duke William II., the greatest of his line. The substantial truth of the legend has never been called in question, and we may still read in safety how Robert, the young count of the Hiesmois, the Son of Duke Richard I. and the fourth in descent from Rollo, was riding towards his capital of Falaise when he saw Arlette, the daughter of a tanner in the town, washing linen in a stream, according to one account—dancing, according to another; how he fell in love at first sight, and carried her off straightway to his castle; and how the connection thus begun lasted unbroken until Robert’s death seven or eight years later. The whole course of William’s early history was determined by the fact of his illegitimacy, and the main points of the story as we have it must already have been known to the citizens of Alençon when they cried out “Hides for the tanner” as the duke came up to their defences in the famous siege of 1049. In fact, the tale itself 64is thoroughly in keeping with the sexual irregularity which was common to the whole house of Rollo, with the single exception of the great Conqueror himself, and we may admit that there is a certain dramatic fitness in this unconventional origin of the man who more than any other of his time could make very unpromising conditions the prelude to brilliant results.[31] The exact date of William’s birth is not certain; it is very probable that it fell between October and December, 1027, but in any case it cannot be placed later than 1028, a fact which deserves notice, for even at the latter date Robert himself cannot possibly have been older than eighteen and may very well have been at least a year younger.

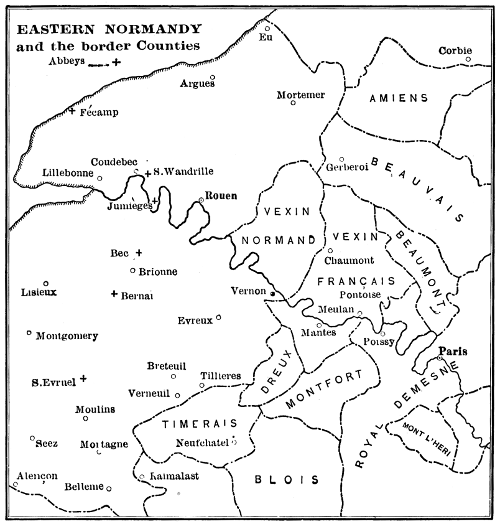

EASTERN NORMANDY

and the border Counties

The reign of Robert I., by some caprice of historical nomenclature surnamed the Devil, was a brilliant period of Norman history. Succeeding to the ducal throne on the sudden, perhaps suspiciously sudden, death of his brother Richard III., in 1028, Robert, in the six years of his rule, won for the duchy an unprecedented influence in the affairs of the French kingdom. The first duty of a Norman duke, that of keeping his greater vassals in order, Robert seems to have 65performed very effectively; we may perhaps measure the strength of his hand by the outburst of anarchy which followed the news of his death. And his intervention in the general feudal politics of France, interesting enough in itself, gains in importance when viewed with reference to the history of his greater son. William the Conqueror inherited the rudiments of a policy from his father; throughout much of his reign he was following lines of action which had been suggested between 1028 and 1035.

This was so with reference to the greatest of all his achievements, the conquest of England. There seems no reason to doubt that Robert had gone through the form of marriage with Estrith, the sister of Cnut, and there is a strong probability that he planned an invasion of England on behalf of the banished sons of Ethelred. The marriage of Robert’s aunt, Emma, first to Ethelred and then to Cnut,[32] began, as we have seen, that unbroken connection between England and Normandy which culminated in the Norman Conquest. Norman enterprise was already in Robert’s reign extending beyond the borders of the French kingdom to Spain and Italy; that it should also extend across the Channel would not be surprising, for Normandy was connected with England by commercial as well as dynastic ties. And William of Jumièges, writing within fifty years of the event, has given a circumstantial 66account of Robert’s warlike preparations. According to him the invasion of England was only prevented by a storm, which threw the duke and his cousin Edward, who was accompanying him, on to the coast of Jersey. Robert does not seem to have repeated the attempt, and before it was made again England had suffered a more subtle invasion of Norman ideas under the influence of Edward the Confessor.

Nor was Norman intervention lacking at the time beyond the western border of the duchy. Robert had inherited old claims to suzerainty over Brittany, and he tried to make them a reality. For some time past Normandy and Brittany had been drawing nearer to each other; Robert was himself a Breton on his mother’s side, and if one aunt of his was queen of England, another was the dowager countess of Brittany. Breton politics were never quite independent of one or other of the great powers of north France, Normandy, Anjou, or Blois, each of which could put forward indeterminate feudal claims over the peninsula. Anjou, under its restless, aggressive counts, was here as elsewhere a formidable rival to Normandy, and in face of its competition Robert could not allow his claims on Brittany to lapse. Hence, when Count Alan repudiated his homage, a Norman invasion followed, the result of which was a fresh recognition of Robert’s overlordship, and the establishment of still closer relations between 67the two states.[33] Alan is found acting as one of the guardians of William’s minority—in fact he died, probably from poison, while besieging the revolted Norman castle of Montgomery in his ward’s interest—and his successor Conan was never really friendly towards Normandy. Yet, notwithstanding his hostility, Norman influence steadily gained the upper hand in Brittany during William’s life. It is significant that he drew more volunteers for his invasion of England from Brittany than from any other district not under his immediate rule.

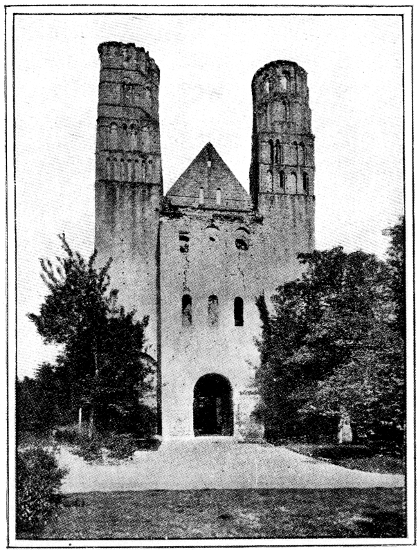

JUMIÈGES ABBEY—FAÇADE

The relations of Robert with the French crown were still more important. The ancient alliance between the dukes of Normandy and the Capetian dynasty which William inherited, and which was to be his chief safeguard during the first fifteen years of his reign, had been greatly strengthened by the action taken by Robert in the internal affairs of the Isle de France. One of the few threads of consistent policy which run through the complicated history of this period is the persistent mistrust of successive kings of France towards their formidable neighbours, the counts of Blois. The possessions of the latter lay astride the royal demesne in two great blocks, the county of Blois, which bordered it on the west, and the county of Troyes or Champagne, which lay along its eastern frontier. The whole territorial group far exceeded the royal possessions 68in extent and resources, and its geographical position gave its lords the strategical advantage as well. Accordingly, the French kings were driven to seek countervailing support among their greater vassals, and at this time they found it in the duchy of Normandy. A similar alliance had been formed in the tenth century against the Carolingians; the traditional friendship was readily adapted to new conditions.

Its value was clearly proved by the events which followed the death of King Robert the Pious. Henry, his eldest surviving son, had been associated with him in the kingship and designated as his successor, but Constance the queen dowager intrigued against the eldest brother in favour of her younger son Robert. Odo II., the able and ambitious count of Blois, took the side of the latter and drove Henry out of the royal demesne. He fled to Normandy and was well received by Robert; there exists a charter of the latter to the abbey of St. Wandrille which Henry attests as a witness in company with his fellow-exiles, Edward, afterwards king and confessor, and Edward’s unlucky brother the Etheling Alfred.[34] Well supported with Norman auxiliaries Henry returned and conquered the royal demesne piecemeal; and, in return for Robert’s help, we are told that the king ceded to him the Vexin Français, the district between the Epte and the Oise.[35]

69The internal condition of Normandy at this period might perhaps compare favourably with that of any of the greater fiefs of north France. A succession of able dukes had, for the time being, reduced the Norman baronage to something like order. Other countries also at this time offered a fairer field for the exercise of superfluous activity; the more unquiet spirits went off to seek their fortune in Spain or Italy. But in Normandy, as elsewhere, everything depended on the head of the state. All the familiar features of feudal anarchy, from the illicit appropriation of justice and the right of levying taxes to simple oppression and private war, were still ready to break out under a weak ruler. And there existed an additional complication in the large extent of territory which was in the hands of members of the ducal house. The lax matrimonial relations of the early dukes had added a very dangerous element to the Norman nobility in the representatives of illegitimate or semi-legitimate lines of the reigning family. They are collectively described by William of Jumièges as the “Ricardenses,” and he tells us with truth that it was these oblique kinsmen of William who felt most aggrieved at, and offered most opposition to, his accession. They were especially formidable from the practice, which had been followed by the early dukes, of assigning counties to younger brothers of the 70intended heir. Duke Robert himself had before his accession held the county of the Hiesmois. Of the illegitimate sons of Richard I., Robert, archbishop of Rouen, the eldest, held in his lay capacity the county of Evreux; his next brother, Malger, the county of Mortain; his youngest brother, William, the county of Eu; while William, the youngest son of Richard II., possessed the county of Arques. It is noteworthy that each of these appanages was, at one period or another in the life of William, the scene of a real or suspected revolt against him.

Such was the general condition of the Norman state when Robert, in the winter of 1034, meditating a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, held a council at Fécamp to decide who should be his successor in case of misadventure, and brought with him in that capacity his seven-year-old son William.[36] Notwithstanding the discreet reticence of the later writers who describe the scene, we can see that the proposal was intensely distasteful to the Norman baronage. To any law-abiding section of the assembly it must have meant entrusting the welfare of the duchy to the most doubtful of hazards, and it was a direct insult to the family pride of the older Norman nobility. Had there existed at this time any member of the ducal house who combined legitimacy of birth with reasonable proximity in the scale of 71succession, Duke Robert would undoubtedly have had the greatest difficulty in carrying his point. But among his many kinsmen there was not one who did not labour under some serious disqualification. Nicholas, the illegitimate son of Richard III., would have been a possible claimant, but Duke Robert had taken the precaution of compelling him, child as he was, to become a monk, and he was now safely bestowed in the ducal monastery of Fécamp.[37] Guy of Brionne, the son of Robert’s sister, was legitimate indeed, but was younger than William, and would be counted a member of a foreign house; Malger and William, Robert’s two surviving brothers, were both illegitimate, and the former was a churchman. Members of the older line, descending from Richard I., probably stood too far back from the line of succession to admit of their appearance as serious competitors, and after all there was a strong probability that the question would not become a matter of immediate importance. Pilgrimages to Jerusalem were not infrequent events at this time[38] and Robert’s age was considerably under thirty. He had previously secured the assent of his overlord King Henry to his proposed heir, and the end of the deliberations at Fécamp was the recognition of William by the Normans as their future duke.

72As it happened, Duke Robert’s pilgrimage turned out ill; he died on the homeward journey, at Nicea, on the second of July, 1035, and the government fell to William, or rather to the guardians whom his father had provided for him before his departure. Of these the highest in rank was Count Alan of Brittany, William’s cousin,[39] with whom were associated Count Gilbert of Brionne, the ancestor of the mighty house of Clare,[40] Osbern the seneschal of Normandy, and a certain Thorold or Thurcytel de Neufmarché, the latter having personal charge of the young duke. It was an ominous circumstance that each of these men came to a violent end within five years of William’s accession. The house of Montgomery alone accounted for two of them: Osbern the seneschal was cut down in William’s bedroom by William, son of Roger de Montgomery; Count Alan met his death, as we have seen, during the siegesiege of Montgomery Castle itself. The assassins of Thurcytel de Neufmarché are not recorded by name, and a certain amount of confusion hangs over the end of Count Gilbert of Brionne; but William of Jumièges, a good authority, states that he fell a victim to murderers hired by Ralf de Wacy, the son of Archbishop Robert of Rouen. It is at least certain that shortly after this last event Ralf de Wacy was 73chosen by William himself, acting, as is said, upon the advice of his chief men, as his guardian and the commander of the Norman army.

More important than this list of crimes is the general question of the relations which existed at this critical period between William and the king of France. We have seen that Duke Robert had secured the king’s consent to his nomination of William as the heir of Normandy; and we have good reason for believing that William after his accession was, in the feudal sense of the phrase, under the guardianship of his overlord. Weak as the French monarchy seems to be at this time it had not, thus early in the eleventh century, finally become compelled to recognise the heritable character of its greater fiefs. Its chances of interfering with credit would vary with each occasion. If a tenant in chief were to die leaving a legitimate son of full age, the king in normal cases would not try to change the order of inheritance; but a dispute between two heirs, or the succession of a minor, would give him a fair field for the exercise of his legal rights. Now William of Normandy was both illegitimate and a minor and his inheritance was the greatest fief of north France; by taking up the office of guardian towards him the king would at once increase the prestige of the monarchy, and also strengthen the ancient friendship which existed between Paris and Rouen. Nor are we left without direct evidence on this point. William of Malmesbury, 74in describing the arrangements made at Fécamp, tells us that Count Gilbert of Brionne, the only one of William’s guardians whom he mentions by name, was placed under the surveillance of king Henry[41]; and Henry of Huntingdon incidentally remarks that in 1035 William was residing with the king of France and that the revenues of Normandy were temporarily annexed to the royal exchequer. In view of the statements of these independent writers, combined with the antecedent probability of the case, we may consider it probable that William, on his father’s death, became the feudal ward of his suzerain,[42] and that very shortly after his own accession he spent some time in attendance at the royal court.

It must be confessed that we know very little as to the events of the next ten years of William’s life. They were critical years, for in them William was growing up towards manhood and receiving the while a severe initiation into the art of government. The political conditions of the eleventh century did not make for quiet minorities; they left too much to the strength and discretion of the individual ruler. Private war, for instance, might be a tolerable evil when duly regulated and sanctioned by a strong duke; under the rule of a child the custom merely supplied a formal excuse 75for the prevailing anarchy. Later writers give various incidental illustrations of the state of Normandy at this period. We read, for instance, how Roger de Toeny, a man of most noble lineage, on returning to Normandy from a crusade against the Moors in Spain, started ravaging the land of his neighbours in sheer disgust at the accession of a bastard to the duchy, and was killed in the war which he had provoked.[43] But such stories only concern the history of William the Conqueror in so far as they indicate the nature of the evils the suppression of which was to be his first employment in the coming years. To turn the fighting energy inherent in feudal life from its thousand unauthorised channels, and to direct it towards a single aim controlled and determined by himself, was to be the work which led to his greatest achievements. In the incessant tumults of the first ten years of his reign we see the aimless stirring of that national force which it is William’s truest glory to have mastered and directed to his own ends.

We get one glimpse of William at this time in a charter[44] which must have been granted before 1037, as it is signed by Archbishop Robert of Rouen, who died in that year. The document is of interest as it shows us the young duke surrounded by his court, perhaps at one of the great church 76festivals of the year. Among the witnesses we find Counts Waleran of Meulan, Enguerrand of Ponthieu, and Gilbert of Brionne; the archbishop of Dol, as well as his brother metropolitan of Rouen; Osbern the seneschal, and four abbots, including the head of the house of Fécamp, in whose favour the charter in question was granted. The presence of the count of Ponthieu and the archbishop of Dol is important as showing that even at this stormy time the connection between Normandy and its neighbours to east and west had not been wholly severed; and it is interesting to see two of William’sWilliam’s unlucky guardians actually, in attendance on their lord. It may also be noted that at least one other charter[45] has survived, probably a little later in date, but granted at any rate in or before 1042, in which among a number of rather obscure names we find the signature of “Haduiardus Rex,” which strange designation undoubtedly describes Edward of England, then nearing the end of his long exile at the court of Normandy.

To this difficult period of William’s reign must apparently be assigned a somewhat mysterious episode which is recorded by William of Jumièges alone among our authorities. One of the strongest border fortresses of Normandy was the castle of Tillières, which commanded the valley of the Arve and was a standing menace to the county of Dreux. The latter was at this time in the 77hands of the crown, but in the tenth century it had been granted to Richard the Fearless, duke of Normandy. He had ceded it to Count Odo of Blois as the marriage portion of his daughter Mahaut, but on her speedy death without issue Odo had refused to return it to his father-in-law; and in the border warfare which followed, the duke founded the castle of Tillières as a check upon his acquisitive neighbour.[46] On Odo’s death in 1018 the county of Dreux passed to his overlord the king of France, but Tillières continued to threaten this latest addition to the royal demesne. We know very little as to what went on in the valley of the Arve during the twenty years that followed Odo’s death, but by the beginning of William’s reign it seems certain that the Norman claims on Dreux itself had been allowed to lapse, and the present dispute centres round Tillières alone. At some unspecified period in William’s minority we find King Henry declaring that, if William wished to retain his friendship, Tillières must be dismantled or surrendered. The young duke himself and some of his barons thought the continued support of the king of France more valuable than a border fortress and were willing to surrender the castle; but its commander, one Gilbert Crispin, continued to hold out against the king. Tillières was thereupon besieged by a mixed force of Frenchmen and Normans, and William, possibly appearing in person, ordered 78Gilbert Crispin to capitulate. He obeyed with reluctance and the castle was at once burned down, the king swearing not to rebuild it within four years, but within the stipulated period it seems that the treaty was broken on the French side. The king at first retired, but not long afterwards he recrossed the border, passed across the Hiesmois, burned Argentan, and then returning rebuilt the castle of Tillières in defiance of his oath, while at the same time it would appear that the viscount of the Hiesmois, one Thurstan surnamed “Goz,” was in revolt against William and had garrisoned Falaise itself with French troops. Falaise was at once invested, William again appearing on the scene to support Ralf de Wacy, the commander of his army, and it seemed probable that the castle would be taken by storm; but Thurstan Goz was allowed to come to terms with the duke and was banished from Normandy, his son Richard continuing in William’s service as viscount of Avranches. The family is of great interest in English history, for Hugh the son of the latter Richard was to become the first earl “palatine” of Chester. And so it may be well to note in passing that the rebel Thurstan is described by William of Jumièges as the son of Ansfrid “The Dane,” a designation which is of interest both as proving the Scandinavian origin of the great house of which he was the progenitor, and also as suggesting that a connection, of which we have few certain traces, may have been 79maintained between Normandy and its parent lands for upwards of a century after the treaty of Claire-sur-Epte.

The above is the simplest account that we can give of these transactions, which are not very important in themselves, but have been considered to mark the rupture of the old friendship between the Capetian dynasty and the house of Rollo.[47] But the whole subject is obscure. The king’s action, in particular, is not readily explicable on any theory, for there is good reason to believe that at this time he was actually William’s feudal guardian and certainly a few years later he appears as fully discharging the duties of that office on the field of Val-es-dunes; so that it is not easy to see why on the present occasion he should inflict gratuitousgratuitous injury on his ward by sacking his towns and burning his castles. The affair of Tillières would be quite intelligible if it stood by itself: it was only natural that the king should take advantage of his position to secure the destruction or surrender of a fortress which threatened his own frontier, and the fact that William himself appears as ordering the surrender would alone suggest that he was acting under the influence of his overlord. But the raid on Argentan is a more difficult matter. We do not know, for instance, whether there was any connection between the revolt of Thurstan Goz 80and the king’s invasion of the Hiesmois; the mere fact that the rebel commander of Falaise took French knights into his pay, by no means proves that he was acting in concert with the French king. The story as we have it suggests that there may have been two parties in Normandy at this time, one disposed to render obedience to the king of France as overlord, the other maintaining the independence of the Norman baronage; a state of affairs which might readily lead to the armed intervention of the king of France, half in his own interest, half in that of his ward. But considering the fact that we owe our knowledge of these events to one chronicler only, and that he wrote when the rivalry between Normandy and France had become permanent and keen, we may not improbably suspect that he antedated the beginning of strife between these two great powers, and read the events of William’s minority in the light of his later history.

The revolt of western Normandy which took place in the year 1047 marks the close of this obscure and difficult period in William’s life; it is in the crisis of this year that something of the personality of the future Conqueror is revealed to us for the first time. With the battle of Val-es-dunes William attained his true majority and became at last the conscious master of his duchy, soon to win the leading place among the greater vassals of the French crown. For ten years more, indeed, he was to be confronted, at first by 81members of his own family, whose ill-will became at times something more than passive disaffection, and afterwards by his overlord made jealous by his increasing power, but the final issue was never again in serious doubt after his barons had once tried conclusions with him in pitched battle and had lost the game.

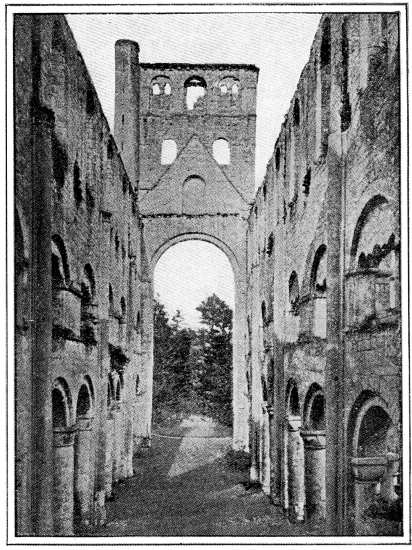

JUMIÈGES ABBEY—INTERIOR

For all this, the revolt of 1047 came near putting a summary close to William’s career and life. Normandy at this time was far from being a homogeneous state; apart from the general tendency of feudalism towards the isolation of individual barons, the greater divisions of the duchy had as yet little real cohesion; and a line of cleavage which is all-important in this revolt is marked by the river Dive, which separates Rouen and its territory, where the ducal power might be expected to be at its strongest, from the lands of the Bessin and Cotentin, which were always predisposed to local independence. These districts, as we have seen, formed no part of the territory ceded to Rollo by the treaty of Claire-sur-Epte, and it is quite possible that the course of events in the present year may have been affected by the distinction between the Gallicised Northmen of the Rouennais and Evrècin and the more primitive folk of the lands west of Dive. At any rate it was from the latter quarter that the main strength of the rising was drawn. The BessinBessin and Cotentin revolted under their respective viscounts, Randolf de Brichessart and 82Neel de Saint Sauveur, the latter being the most prominent leader in the whole affair; and with them were associated one Hamo, nicknamed “Dentatus,” the lord of Thorigny and Creuilly, and Grimbald the seigneur of Plessis. The nominal head of the revolt was William’s cousin Guy, son of Reginald, count of the Burgundian Palatinate by Adeliz, daughter of Duke Richard II. of Normandy, a young man, who up to this time had been the constant companion of William, and had received from him Brionne and Vernon, two of the most important castles of eastern Normandy. Guy was one of the few legitimate members of the ducal family, and he and his confederates found a justification for their rising in the stain which rested upon William’s birth. We are told that their ultimate object was to divide the duchy among themselves, and we may suppose that Guy would have taken Rouen and the surrounding country with the title of duke, leaving the western lords in practical independence. The latter took an oath to support his claims and to depose William, and they put their castles into a state of defence.

When the revolt broke out William was in the heart of the enemies’ country at Valognes, a town which seems to have been his favourite hunting seat in the west of Normandy. The opportunity was too good to be missed, and a plot was laid for his capture which came within an ace of success, and according to later tradition 83was only discovered, on the point of its execution, by Gallet, William’s fool. The duke had gone to bed when Gallet burst into his room and called on him to escape for his life. Clad in such garments as came to hand William sprang on horseback, and rode away through the dead of night eastwards towards his native and loyal town of Falaise. He took the coast road, crossing the estuary of the Vire at low water, and by day-break he had covered the forty miles which separate Valognes from Rye. It so chanced that Hubert the lord of Rye was standing between his castle mound and the neighbouring church as the duke came riding by, and recognising his lord he asked the reason of his haste. Upon learning of his danger Hubert called three of his sons and bade them escort the duke to Falaise; but even in the capital of his native province William made no delay, and hastened across the borders of his duchy to ask help of his overlord and guardian, King Henry of France.[48] The king and the duke met at Poissy, and a French army prepared to enter Normandy under the leadership of the king in person, while on his part William summoned the men of Rouen, Auge, Lisieux, Evreux, and the Hiesmois, men, that is, from all Normandy east of the Dive and from the territory belonging to Falaise, west of that 84river. The Normans assembled in the latter district and concentrated on the Meance near Argences; the French army drew together on the Laison between Argences and Mezidon. King Henry heard mass and arranged his troops at Valmeray, then crossed the Olne on to the plain of Val-es-dunes and drew up his men on the bank of the river. In that position he was joined by William, who had crossed at the ford of Berangier, and the combined force prepared for battle, the Frenchmen forming the left wing and the Normans the right.[49]

In the meantime the revolt had spread apace. The rebels had seized the duke’s demesne and, it would seem, were prepared to invade the loyal country across the Dive, for they had reached Val-es-dunes before the king and the duke had arrived there. Like their opponents, they drew up their army in two divisions, the men of the Cotentin forming the right wing and those of the Bessin the left. The battle seems to have begun by a charge of the Cotentin men on the French, but of the struggle which followed we have only a confused and indefinite account; it appears to have been a simple cavalry encounter, calling for no special tactical skill in the leaders of either side. Even in most of the Norman accounts of the battle William plays a part distinctly secondary to that of his overlord, although the latter had the ill luck to be unhorsed twice 85during the day, once by a knight of the Cotentin and once by the rebel leader Hamo “Dentatus.” Before long the fight was going decisively in favour of the loyal party. The rebel leaders seem to have mistrusted each other’s good faith. In particular Ralf of Brichessart began to fear treachery; he suspected that Neel de Saint Sauveur might have left the field, while one of his own most distinguished vassals had been cut down before his eyes, by the duke’s own hand as later Norman tradition said. Accordingly, long before the fight was over he left the field, but the western men were still held together by Neel, who made a determined stand on the high ground by the church of St. Lawrence. At last he too gave way, the flight became general, and it was at this point that the rebel force suffered its heaviest losses, for the broken army tried to make its way into the friendly land of the Bessin, and the river Olne lay immediately to the west of the plateau of Val-es-dunes. Large numbers of the rebels perished in the river and the rest escaped between Alegmagne and Farlenay, while Guy himself, who had been wounded in the battle, fled eastward to his castle of Brionne.

The reduction of this fortress must have been for William the most formidable part of the whole campaign. Even in the middle of the eleventh century the art of fortification was much more fully developed than the art of attack, and at Brionne the site of the castle materially aided 86the work of defence. The castle itself stood on an island in the river Risle, which at that point was unfordable, and it was distinguished from the wooden fortifications common at the time by the fact that it contained a stone “hall,” which was evidently considered the crowning feature of its defences.[50] Immediately, it would seem, after the battle of Val-es-dunes King Henry retired to France, while William hastened to the siege of Brionne. A direct attack on the castle being impossible, William built counterworks on either bank of the Risle and set to work to starve the garrison into surrender. By all accounts the process took a long time,[51] but at last the failure of supplies drove Guy to send and ask for terms with William. These were sufficiently lenient; Guy was required to surrender Brionne and Vernon, but was allowed to live at William’s court if he pleased. No very drastic measures were taken with regard to the rebels of lower rank, but William, realising with true instinct where his real danger had lain, dismantled the castles which had been fortified against him; and with the disappearance of the castles the fear[52] of 87civil war vanished from Normandy for a while. The capital punishment of rebellious vassals was not in accordance with the feudal custom of the time.[53] The legal doctrine of sovereignty, which made the levying of war against the head of the state the most heinous of all crimes, was the creation of the revived study of Roman law in the next century; and a mere revolt, if unaggravated by any special act of treason, could still be atoned for by the imprisonment of the leaders and the confiscation of their lands. To this we must add that William as yet was no king, the head of no feudal hierarchy; the distance that separated him from a viscount of Coutances was far less than the distance that came to separate a duke of Somerset from Edward IV. The one man who was treated with severity on the present occasion was Grimbald of Plessis, on whom was laid the especial guilt of the attempt on William’s life at Valognes. He was sent into perpetual imprisonment at Rouen, where he shortly died, directing that he should be buried in his fetters as a traitor to his lord.[54] Guy of Burgundy seems to have become completely discredited by his 88conduct in the war, life in Normandy became unbearable to him, and of his own free will he retired to Burgundy, and vanishes from Norman history.

The war was over, and William’s future in Normandy was secured, but the revolt had indirect results which extended far beyond the immediate sequence of events. It was William’s duty and interest to return the service which King Henry had just done to him, and it was this which first brought him into hostile relations with the rising power on the lower Loire, the county of Anjou. The history of Anjou is in great part the record of a continuous process of territorial expansion, which, even by the beginning of the eleventh century had raised the petty lordship of Angers to the position of a feudal power of the first rank. Angers itself, situated as it was in the centre of the original Anjou, was an excellent capital for a line of aggressive feudal princes, who were enabled to strike at will at Brittany, Maine, Touraine, or Saintonge, and made the most of their strategical advantage. With Normandy the counts of Anjou had not as yet come into conflict; the county of Maine had up to the present separated the two states, and the collision might have been indefinitely postponed had not the events of 1047 compelled William of Normandy to bear his part in a quarrel which shortly afterwards broke out between the king of France and Count Geoffrey II. of Anjou.

89The first five years of William’s minority had coincided, in the history of Anjou, with the close of the long reign of Count Fulk Nerra, who for more than fifty years had been extending the borders of his county with unceasing energy and an entire absence of moral scruple, and has justly been described as the founder of the Angevin state. His son and successor Geoffrey, commonly known in history, as to his contemporaries, under the significant nickname of Martel, continued his father’s work of territorial aggrandisement. He had three distinct objects in view: to round off his hereditary possessions by getting possession of Touraine, and to extend his territory to the north and south of the Loire at the expense of the counts of Maine and Poitou respectively. His methods, as described by Norman historians, were elementary; his favourite plan was to seize the person of his enemy and allow him to ransom himself by the cession of the desired territory. This simple device proved effective with the counts of Poitou and Blois; from the former, even before the death of Fulk Nerra, Geoffrey had extorted the cession of Saintonge, and from the latter, after a great victory at Montlouis in 1044, he gained full possession of the county of Touraine. The conquest of Touraine was undertaken with the full consent of the king of France; the counts of Blois, as we have seen, were ill neighbours to the royal demesne, and King Henry and his successors were always 90ready to ally themselves with any power capable of making a diversion in their favour. On the other hand their policy was not, and could not be, consistent in this respect; the rudimentary balance of power, which was all that they could hope to attain at this time, was always liable to be overthrown by the very means which they took to preserve it; a count of Anjou in possession of Saintonge and Touraine could be a more dangerous rival to the monarchy than the weakened count of Blois. Accordingly, less than four years after the battle of Montlouis, we find King Henry in arms against Geoffrey Martel, and William of Normandy attracted by gratitude and feudal duty into the conflict.[55]

When William, archdeacon of Lisieux, the Conqueror’s first biographer, was living, an exile as he styles himself, in Poitou shortly after this time, the prowess of the young duke in this campaign was a matter of current conversation.[56] The Frenchmen, we are told, were brought to realise unwillingly that the army led by William from Normandy was greater by far than the whole force supplied by all the other potentates who took part in the war. We are also told that King Henry had the greatest regard for his protégé, took his advice on all military matters, and remonstrated with him affectionately on his too 91great daring in the field. William seems in his early days to have possessed a full share of that delight in battle which is perhaps the main motive underlying the later romances of chivalry, and his reputation rose rapidly and extended far. Geoffrey Martel himself said that there could nowhere be found so good a knight as the duke of Normandy. The princes of Gascony and Auvergne and even the kings of Spain sent him presents of horses and tried to win his favour.[57] Also it must have been about this time that William made overtures to Baldwin, count of Flanders, for the hand of his daughter, while in 1051 we know that he made a journey, fraught with memorable consequences, to the court of Edward the Confessor. In fact, with the subjugation of his barons and his first Angevin war William sprang at a bound into fame; the political stage of France lacked an actor of the first order, and William in the flush of his early manhood was an effective contrast to the subtle and dangerous count of Anjou.

At some undetermined point in the war an opportunity presented itself for Geoffrey Martel to gain a foothold in Norman territory. On the border between Normandy and Maine stand the towns of Domfront and Alençon, each commanding a river valley and a corresponding passage from the south into Normandy. Domfront formed part of the great border fief of Bellême, and at 92this time it was included in the county of Maine, over which, as we shall see later, Geoffrey Martel was exercising rights of suzerainty. Alençon was wholly Norman, but its inhabitants found William’s strict justice unbearable, and being thus predisposed for revolt they admitted a strong Angevin garrison sent by Geoffrey Martel. William decided to retaliate by capturing Domfront, leaving Alençon to be retaken afterwards.[58] The plan was reasonable, but it nearly led to William’s destruction, for a traitor in the Norman army gave information as to his movements to the men of Domfront, and it was only through his personal prowess that William escaped an ambush skilfully laid to intercept him as he was reconnoitring near the city. The siege which followed was no light matter. It was winter, Geoffrey had thrown a body of picked men into the castle, and, unlike Brionne, Domfront was a hill fortress, accessible at the time only by two steep and narrow paths. It would thus be difficult to carry the place by sudden assault; so William, as formerly at Brionne and later at Arques, established counterworks and waited for the result of a blockade, harassing the garrison meanwhile by incessant attacks on their walls. The counterworks, we are told, consisted of four “castles,” presumably arranged so as to cover the base of the hill on which Domfront stands, and William contented himself for the present 93with securing his own supplies and preventing any message being carried from the garrison to the count of Anjou, in the meantime making use of the opportunities for sport which the neighbouring country offered. At last the men of Domfort contrived to get a messenger through the Norman lines and Geoffrey advanced to the relief of his allies with a large army. What followed may be told in the words of William of Poitiers:

“When William knew this he hastened against him [Geoffrey], entrusting the maintenance of the siege to approved knights, and sent forward as scouts Roger de Montgomery and William fitz Osbern, both young men and eager, who learned the insolent intention of the enemy from his own words. For Geoffrey made known by them that he would beat up William’s guards before Domfront at dawn the next day, and signified also what manner of horse he would ride in the battle and what should be the fashion of his shield and clothing. But they replied that he need trouble himself no further with the journey which he designed, for he whom he sought would come to him with speed, and then in their turn they described the horse of their lord, his clothing and arms. These tidings increased not a little the zeal of the Normans, but the duke himself, the most eager of all, incited them yet further. Perchance this excellent youth wished to destroy a tyrant, for the senate of Rome and Athens held such an act to be the fairest of all noble deeds. But Geoffrey, smitten with sudden terror, before he had so much as 94seen the opposing host sought safety in flight with his whole army, and lo! the path lay open whereby the Norman duke might spoil the wealth of his enemy and blot out his rival’s name with everlasting ignominy.”[59]

It is painful to pass from this rhapsody to what is perhaps the grimmest scene in William’s life. The retreat of Geoffrey, to whatever cause it is to be assigned, exposed Alençon to William’s vengeance. Leaving a sufficient force before Domfront to maintain the siege, in a single night’s march he crossed the water-parting of the Varenne and the Sarthe, and approached Alençon as dawn was breaking. Facing him was the fortified bridge over the Sarthe, behind it lay the town, and above the town stood the castle, all fully defended. On the bridge certain of the citizens had hung out skins, and as William drew near they beat them, shouting “Hides for the tanner.”[60] With a mighty oath the young duke swore that he would prune those men as it were with a pollarding knife, and within a few hours he had executed his threat. The bridge was stormed and the town taken, William unroofing the houses which lay outside the wall and using the timber as fuel to burn the gates, but the castle still held out. Thirty-two of the citizens were then brought before the duke; their hands and feet were struck off and flung straightway over the wall of the castle 95among its defenders.[61] With the hasty submission of the castle which followed William was free to give his whole attention to the reduction of Domfront, and on his return he found the garrison already demoralised by the news of what had happened at Alençon, and by the ineffective departure of Geoffrey Martel. They made an honourable surrender and Domfront became a Norman possession,[62] the first point gained in the struggle which was not to end until a count of Anjou united the thrones of Normandy, Maine, and England.

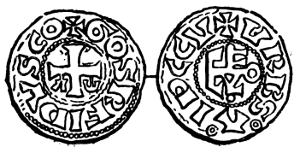

Denier of Geoffrey Martel

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content