Search london history from Roman times to modern day

Up to the present we have only dealt with the ecclesiastical relations of William the Conqueror in so far as they have directly affected political issues. But the subject has a unity of its own, quite apart from its bearing upon the course of war or diplomacy, and no aspect of the Conqueror’s work is known to us in greater detail. It may be added that no aspect of the Conqueror’s work is more illustrative of the general character of his government, nor of greater significance for the future history. For four centuries and a half the development of the church in England followed the lines which he had indicated.[287]

But the church in Normandy was William’s first concern, and some appreciation of his work here is necessary to an understanding of the tendencies which governed his ecclesiastical policy in England. Broadly stated, William’s relations with the church in Normandy and England alike were governed by two main ideas. He was beyond all doubt sincerely anxious for the reform 377of the church, as he would have understood the phrase—the extension and stricter observance of the monastic life, the improvement of the learning and morals of the secular clergy, the development of a specific ecclesiastical law. But he was no less determined that, at all hazards, the church in his dominions should be subordinate to the state, and his enforcement of this principle ultimately threw him into opposition to the very party in the church which was most sympathetic to his plans of ecclesiastical reform. Between Hildebrand claiming in definite words that the head of the church was the lord of the world, and William asserting in unmistakable acts that the king of England was over all persons in all causes, as well ecclesiastical as temporal, through his dominions supreme, there were certain to be differences of opinion. But the two great men kept the peace for a surprising length of time, and it was not until ten years before William’s death that serious discord arose between him and the Curia in regard to the question of church government.

In this matter, indeed, William was but maintaining prerogatives which he had inherited from his predecessors, and which were simultaneously being vindicated by the other princes of his time. We have already remarked on the intimate connection of church and state which prevailed in Normandy at the beginning of the eleventh century, in relation to its bearing upon 378the general absolutism enjoyed by the duke. But the fact has a wider significance as governing the whole character of ecclesiastical life in the duchy. The rights of patronage which the duke possessed, his intervention in the process of ecclesiastical legislation, his power of deposing prelates who had fallen under his displeasure, not only forbade the autonomy of the church, they made its spiritual welfare as well as its professional efficiency essentially dependent upon the personal character of its secular head. Under these conditions, there was scanty room for the growth of ultramontane ideas among the Norman clergy; and such influence as the papacy exercised in Normandy before 1066 at least was due much more to traditional reverence for the Holy See, and to occasional respect for the character of its individual occupants, than to any recognition of the legal sovereignty of the Pope in spiritual matters. William himself in the matter of his marriage had defied the papacy, and the denunciations of the Curia found but a faint response among the prelates of the Norman church.

From the ultramontane point of view this dependence of the church upon the state was a gross evil, but it was at least an evil which produced its own compensation in Normandy. The chaos which had attended the settlement of the Northmen in the tenth century had involved the whole ecclesiastical organisation of the land in utter ruin, and its restoration was entirely 379due to the initiative taken by the secular power. The successive dukes of Normandy, from Richard I. onward, showed astonishing zeal in the work of ecclesiastical reform.[288] Their zeal, however, must have spent itself in vain if their success had been dependent upon the co-operation of the Norman clergy; the decay of the church in Normandy had gone too far to permit of its being reformed from within. The reforming energy which makes the eleventh century a brilliant period in French ecclesiastical history was concentrated at this time in the great abbeys of Flanders and Burgundy, whose inmates, however, were fully competent, and for the most part willing, to undertake the restoration of ecclesiastical order in Normandy. From this quarter, and in particular from the abbey of Cluny, monks were imported into the duchy by Dukes Richard I. and II., and under their guidance the reform of the Norman church was undertaken according to the highest monastic ideal of the time. Very gradually, but with ever increasing strength, the influence of the foreign reformers gained more and more control over every rank in the Norman hierarchy. The higher clergy, who at first resisted the movement, became transformed into its champions as the result of the judicious appointments made by successive dukes. Even the upland clergy, whose invincible ignorance had aroused the anger of the earliest reformers, were attracted 380within the scope of the reform, partly by means of the affiliation of village churches to monasteries, but above all through the educational work performed by the schools which were among the first fruits of the monastic revival.

If the foundation of new monasteries may be taken as evidence, the process of expansion and reform went on unchecked throughout the stormy minority of William the Conqueror. A period of feudal anarchy was not necessarily inimical to the ultimate interests of the church. Amid the disorder and oppression of secular life the church might still display the example of a society founded on law and discipline, it might in numberless individual cases protect the weak from gratuitous injury, and it certainly might hope to emerge from the chaos with wider influence and augmented revenues. The average baron was very willing to atone for his misdeeds by the foundation of a new religious house, or by benefactions to an old one, and the immortal church had time on its side. In Normandy, at least, the disorder of William’s minority coincided with the foundation of new monasteries in almost every diocese in the Norman church; and the promulgation of the Truce of God in 1042 gave a wide extension to the competence of ecclesiastical jurisdiction in relation to secular affairs.

With William’s victory at Val-es-dunes, the crisis was over, and for the next forty years the Norman church sailed in smooth waters. Autocratic 381as was William by temperament, nothing contributed more greatly to his success than his singular wisdom in the choice of his ministers in church and state, and his power of attaching them to his service by ties of personal friendship to himself. The relations between William and Lanfranc form perhaps the greatest case in point, but there were other and less famous members of the Norman hierarchy who stood on terms of personal intimacy with their master. And William was cosmopolitan in his sympathies. Men of learning and piety from every part of Christendom were entrusted by him with responsible positions in the Norman church; in 1066 nearly all the greater abbeys of Normandy were ruled by foreign monks. Cosmopolitanism was the chief note of medieval culture, and under these influences a real revival of learning may be traced in Normandy. It is well for William’s memory that this was so; but for the work of William of Poitiers and William of Jumièges, two typical representatives of the new learning, posterity would have remained in blank ignorance of the Conqueror’s rule in Normandy. But it is a matter of still greater importance that in this way Normandy was gradually becoming prepared to be the educator of England, as well as her conqueror. The surviving relics of the literary activity at this time of Normandy—mass books, theological treatises, and books of miracles, which it produced—have but little interest for the general student of history, but the 382important point is that they are symptoms of an intellectual life manifesting itself with vigour in the only directions which were possible to it in the early eleventh century. Not until it had been transplanted to the conquered soil of England did this intellectual life produce its greatest result, the philosophical history of William of Malmesbury, the logical narrative of Eadmer, to name only two of its manifestations; but in matters of culture, as well as in matters of policy and war, the Norman race was unconsciously equipping itself in these years for its later achievement across the Channel.

It cannot be denied that the English church stood in sore need of some such external influence. The curious blight which seemed to have settled on the secular government of England affected its religious organisation also. The English church had never really recovered from the Danish wars of Alfred’s time. It had been galvanised into fresh activity by the efforts of Dunstan and his fellow-reformers of the tenth century, but the energy they had infused scarcely outlasted their own lives, and in 1066 the church in England compares very unfavourably with the churches of the continent in all respects. It had become provincial where they were catholic; its culture was a feeble echo of the culture of the eighth century, they were striking out new methods of inquiry into the mysteries of the faith; it was becoming more and more closely assimilated to 383the state, they were struggling to emancipate themselves from secular control. There was ample scope in England for the work of a great ecclesiastical reformer, but the increasing secularisation of the leaders of the church rendered it unlikely that he would come from within.

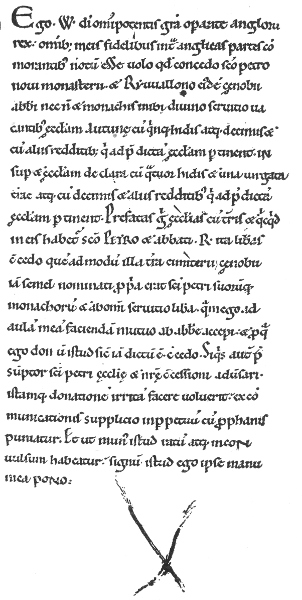

REDUCED FACSIMILE OF THE CHARTER OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR TO HYDE ABBEY

Even in 1066 the English church still retained distinct features of the tribal organisation which it had inherited from the century of the conversion. Its dioceses in general represented Heptarchic kingdoms, and the uncertainty of their boundaries is here and there definitely traceable to the uncertain limits of the primitive tribes of which, they were the ecclesiastical equivalents. The residences of half the English bishops of the eleventh century were still fixed, like those of their seventh-century predecessors, in remote villages; “places of retirement rather than centres of activity,” as they have well been called. The number of dioceses was very small in proportion to the population and area of the land, and it tended to decrease; Edward the Confessor had recently united the sees of Cornwall and Devon, under the single bishop of Exeter. Within his diocese each bishop enjoyed an independence of archiepiscopal supervision, the like of which was unknown to his continental fellows; the canonical authority of the archbishops was in abeyance, and in 1070 it was still an open question whether the sees of Dorchester, Lichfield, and Worcester, which represented nearly 384a third of England, belonged to the province of Canterbury or of York. The smaller territorial units of ecclesiastical government, the archdeaconry and rural deanery, are hardly to be traced in England before the Conquest, and the chapters in the several dioceses varied indefinitely in point of organisation.

It was not necessarily an abuse that the right of making appointments to the higher ecclesiastical offices belonged in England to the king and the Witanagemot; it was another matter that the leaders of the church were becoming more and more absorbed in secular business. A representative bishop of King Edward’s day would be a vigorous politician and man of affairs. Ealdred, archbishop of York, was sent by the king into Germany to negotiate for the return of Edgar the Etheling; Lyfing of Worcester earned the title of the “eloquent” through the part he played in the debates of the Witanagemot; Leofgar of Hereford, a militant person who caused grave scandal by continuing to wear his moustaches after his ordination, conducted campaigns against the Welsh. In Normandy, this type of prelate was rapidly becoming extinct; Odo of Bayeux and Geoffrey of Coutances stand out glaringly among their colleagues in 1066; but in England the circumstances of the time demanded the increasing participation of the higher clergy in state affairs. The rivalry of the great earls at Edward’s court produced, as it were, a barbarous 385anticipation of party government, and during the long ascendancy of the house of Godwine, ecclesiastical dignities were naturally bestowed on men who could make themselves politically useful to their patron. Curiously enough, the one force which operated to check the secularisation of the English episcopate was the personal character of King Edward. His foreign tendencies found full play here, and the alien clerks of his chapel whom he appointed to bishoprics came to form a distinct group, to which may be traced the beginnings of ecclesiastical reform in England. For a short time the highest office in the English church was held, in the person of the unlucky Robert of Jumièges, by a Norman monk in close touch with the Cluniac school of ecclesiastical reformers, who seems to have tried, during his brief period of rule, to raise the standard of learning among the clergy of his diocese. Robert fell before he could do much in this direction, but the foreign influences which were beginning to play upon the English church did not cease with his expulsion. Here and there, during Edward’s later years, native prelates were to be found who recognised that much was amiss with the church, and followed foreign models in their attempts at reform; Ealdred of York tried to impose the strict rule of Chrodegang of Metz upon his canons of York, Ripon, Beverley, and Southwell, the four greatest churches of Northern England. But individual bishops could not go 386far enough in the work of reform, and their efforts seem to have met with little sympathy from the majority of their colleagues.

To a foreign observer, nothing in the English church would seem more anomalous than the character of its ecclesiastical jurisdiction. There existed, indeed, in the law books of successive kings, a vast mass of ecclesiastical law; it was in the administration of this law that England parted company with continental usage. In England the bishop with the earl presided over the assembly of thegns, freemen, and priests which constituted the shire court, and the local courts of shire and hundred had a wide competence over matters which, on the continent, would have been referred to a specifically ecclesiastical tribunal. The bishop seems to have possessed an exclusive jurisdiction over the professional misdoings of his clergy, and the degradation of a criminous clerk, the necessary preliminary to his punishment by the lay authority, was pronounced by clerical judges, but all other matters of ecclesiastical interest fell within the province of the local assemblies. Ecclesiastical and secular laws were promulgated by the same authority and administered by the same courts, nor does the church as a whole seem to have possessed any organ by means of which collective opinion might be given upon matters of general importance. No great councils of the church, such as those of which Bede tells us, can be traced in 387the Confessor’s reign, nor, indeed, for nearly two centuries before his accession. The church council had been absorbed by the Witanagemot.

To all the greater movements which were agitating the religious life of the continent in the eleventh century—the Cluniac revival, the hierarchical claims of the papacy—the English church as a whole remained serenely oblivious. Its relations with the papacy were naturally very intermittent, and when a native prelate visited the Holy See, he might expect to hear strong words about plurality and simony from the Pope. With Stigand the papacy could hold no intercourse, but, despite all the fulminations of successive Popes, Stigand continued for eighteen years to draw the revenues of his sees of Canterbury and Winchester, and other prelates rivalled him in his offences of plurality, whatever scruples they might feel about his canonical position as archbishop. Ealdred of York had once administered three bishoprics and an abbey at the same time. The ecclesiastical misdemeanours of a party among the higher clergy would have been a minor evil, had it not coincided with the general abeyance of learning and efficiency among their subordinates. We know very little about the parish priest of the Confessor’s day, but what is known does not dispose us to regard him as an instrument of much value for the civilisation of his neighbours. In the great majority of cases, he seems to have been a rustic, married like his parishioners, 388joining with them in the agricultural work of the village, and differing from them only in the fact of his ordination, and in possessing such a knowledge of the rudiments of Latin as would enable him to recite the services of the church. The energy with which the bishops who followed the Conquest laboured for the elevation of the lower clergy is sufficiently significant of what their former condition must have been. The measures which were taken to this end by the foreign reformers—the general enforcement of celibacy, for example—may not commend themselves to modern opinion, but Lanfranc and his colleagues knew where the root of the matter lay. It was only by making the church distinct from the state, by making the parish priest a being separated by the clearest distinctions from his lay brother, that the church could begin to exercise its rightful influence upon the secular life of the nation.

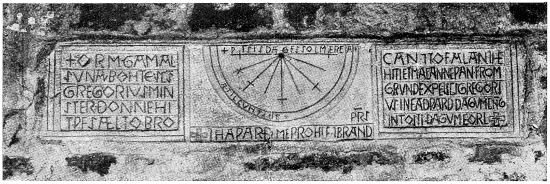

GAMEL SON OF ORME’S SUNDIAL

FROM A SHORT ACCOUNT OF SAINT GREGORY’S MINSTER, KIRKDALE, BY REV. F. W. POWELL, VICAR. THE TRANSLATION IS AS FOLLOWS:

“ORM GAMAL’S SON BOUGHT S. GREGORY’S MINSTER WHEN IT WAS ALL BROKEN DOWN AND FALLEN AND HE LET IT BE MADE ANEW FROM THE GROUND TO CHRIST AND S. GREGORY, IN EDWARD’S DAYS, THE KING, AND IN TOSTI’S DAYS, THE EARL.”

Political circumstances delayed the beginnings of ecclesiastical reform for more than three years after the battle of Hastings had placed the destinies of the English church in Norman hands. While the Conqueror was fighting at Stafford and York, he could not be presiding over synods at Winchester and London. No steps, therefore, were taken in this question before 1070, when the fall of Chester destroyed the last chance of a successful English rising, and made it no longer expedient for William to be complaisant to Stigand 389and the nationalist party in the English episcopate. But in 1070 the work was begun in earnest under the immediate sanction of the Pope, expressed in the legation of two cardinal priests who visited England in that year. There could be little doubt what their first step would be; and when Stigand was formally arraigned for holding the sees of Winchester and Canterbury in plurality, usurping the pallium of his predecessor, Robert, and receiving his own pallium from the schismatic Benedict X., he had no defence to offer beyond declamation against the good faith of the king. Three other bishops fell at or about the same time; Ethelmer, brother of Stigand, and bishop of East Anglia, Ethelwine, bishop of Durham, and Ethelric, bishop of Selsey. In regard to none of these last bishops are the grounds on which their deposition was based at all certain; and in the case of Ethelric, an aged man who was famed for his vast knowledge of Anglo-Saxon law, the Pope himself was uneasy about the point, and a correspondence went on for some time between him and Lanfranc on the subject. But it is a noteworthy fact that these four prelates are the only bishops deposed during the whole of the Conqueror’s reign. Nothing was further from William’s purpose than any wholesale clearance of the native episcopate. He was King Edward’s heir, and he wished, therefore, to retain King Edward’s bishops in office, so far as this was consistent with the designs of his ally the Pope. On the other hand, William was 390no less determined to fill all vacancies when they occurred in the course of nature with continental priests. Herein he and the Pope were in complete harmony. It was only by this means that continental culture and ideas of church government could be introduced into England, and William trusted in his own strength to repress any inconvenient tendencies which might arise from the ultramontane ideals of his nominees.

The deposition of Stigand meant the elevation of Lanfranc to the archbishopric of Canterbury. It is probable that the Pope would have preferred to attach him to the College of Cardinals, but William was determined to place his old friend at the head of the English church, and Alexander II. gave way. York, vacant through the death of Ealdred in 1069, was given to Thomas, treasurer of Bayeux, protégé of Odo, bishop of that see, and a man of vast and cosmopolitan learning. Almost immediately after his appointment a fierce dispute broke out between him and Lanfranc. The dispute in question was twofold—partly referring to the boundaries of the two provinces, but also raising the more important question whether the two English archbishops should possess co-ordinate rank or whether the archbishop of York should be compelled to take an oath of obedience to the primate of Canterbury. In a council held at Winchester in 1072 both questions were settled in favour of Canterbury. The dioceses of Lichfield, Worcester, and 391Dorchester were assigned to the latter provinces, and Lanfranc—partly by arousing William’s fears as to the political inexpediency of an independent archbishop of York, partly by the skilful forgery of relevant documents—brought it about that the northern archbishopric was formally declared subordinate to that of Canterbury. In ecclesiastical, as well as secular matters, William had small respect for the particularism of Northumbria.

The council which decided this matter was only one of a series of similar assemblies convened during the archiepiscopate of Lanfranc. The first of the series had already been held in 1070, when Wulfstan, the unlearned but saintly bishop of Worcester, was arraigned pro defectu scientiæ. He was saved from imminent deposition partly by his piety, partly by his frank and early acceptance of the Norman rule; and he retained his see until his death in 1094. In 1075 the third council of the series proceeded to deal with one of the greatest anomalies presented by the English church, and raised the whole question of episcopal residence. In accordance with its decrees, the see of Lichfield was translated to Chester, that of Selsey to Chichester, and that of Sherborne to Old Salisbury. Shortly afterwards, the seat of the east midland diocese of Dorchester was transferred to Lincoln; and in 1078 Bishop Herbert of Elmham, after an abortive attempt to gain possession of Bury St. Edmund’s, removed his residence to 392Thetford, the second town in Norfolk. In all these changes the attempt was made to follow the continental practice by which a bishop would normally reside in the chief town of his diocese. But new episcopal seats implied new cathedral churches, and the Conqueror’s reign witnessed a notable augmentation of church revenues,[289] expressed in grants of land, the extent of which can be ascertained from the evidence of Domesday Book. Here and there are traces of a reorganisation of church property, and of its appropriation to special purposes; all of which enabled the new bishops to support the strain incurred by their great building activities. By 1087 new cathedrals had been begun in seven out of fifteen dioceses.

The church councils which supplied the means through which the king and primate carried their ideas of ecclesiastical reform into effect were bodies of a somewhat anomalous constitution. In the Confessor’s day the Witanagemot had treated indifferently of sacred and secular law, but its competence in religious matters did not descend unbroken to its feudal representative, the Commune Concilium. In the Conqueror’s reign the church council is becoming differentiated from the assembly of lay barons, but the process is not yet complete. The session of the church council would normally coincide in point of place and time with a meeting of the Commune 393Concilium; no ecclesiastical decree was valid until it had received the king’s sanction, and the king and his lay barons joined the assembly, although they took no active part in its deliberations. There was, indeed, small necessity for their presence, and in two of the more important councils of William’s reign, at London in 1075 and at Gloucester in 1085 the spiritualty held a session of their own apart from the meeting of the Commune Concilium. In any case the spiritual decrees were promulgated upon the authority of the archbishop and prelates, although the royal word was necessary for their reception as law.

No piece of ecclesiastical legislation passed during this time had wider consequences than the famous decree which limited the competence of the shire and hundred courts in regard to matters pertaining to religion.[290] This law has only come down to us in the form of a royal writ addressed to the officers and men of the shire court, so that its exact date is uncertain. But intrinsically it is likely enough that the question of ecclesiastical jurisdiction would be one of the first matters to which William and Lanfranc would turn their hands, and the principle implied in the writ had already been recognised by all the states of the continent. According to this document no person of ecclesiastical status might be tried before the hundred court, nor might 394this assembly any longer possess jurisdiction over cases involving questions of spiritual law, even when laymen were the parties concerned. All these matters were reserved to the exclusive jurisdiction of the bishops and their archdeacons, and in this way room was prepared in England for the reception of the canon law of the church.[291] Important as it was for the subsequent fortunes of the church, this decree was perhaps of even greater importance for its influence upon the development of secular law. The canons of the church, in the shape which they assumed at the hands of Gratian in the next generation, were to set before lay legislators the example of a codified body of law, aiming at logical consistency and inherent reason; a body very different from the collection of isolated enactments which the English church of the eleventh century inherited from the Witanagemots of Alfred and Edgar. We cannot here trace the way in which the efforts of the great doctors of the canon law were to react upon the work of their secular contemporaries; but the fact of such influence is certain, and the next century witnessed its abundant manifestation.

The transference of ecclesiastical causes from the sphere of the folk law to that of the canons of the church meant that the Pope would in time acquire, in fact, what no doubt he would already claim in theory—the legal sovereignty of the 395church in England. That William recognised this is certain, and he was determined that the fact should in no way invalidate the ecclesiastical prerogatives which he already enjoyed in Normandy, and which in regard to England he claimed as King Edward’s heir. Contemporary churchmen say this too, and the key to William’s relations with the Pope is given in the three resolutions which Eadmer in the next generation ascribes to him. No Pope should be recognised in England, no papal letters should be received, and no tenant-in-chief excommunicated without his consent. In short, William was prepared to make concessions to the ecclesiastical ideas of his clerical friends only in so far as they might tend to the more efficient discharge by the church of its spiritual function. This was, of course, a compromise, and no very satisfactory one; it led immediately to strained relations between William himself and Hildebrand, it was the direct cause of the quarrel between William Rufus and Anselm, and it was indirectly responsible for the greater struggle which raged between Henry of Anjou and Becket. On one point, however, king and papacy were in perfect accord, and it was this fact which prevented their difference of opinion upon higher matters of ecclesiastical policy from becoming acute during the Conqueror’s lifetime. Both parties were agreed upon the imperative necessity of reforming the mass of the English clergy in morals and learning, and here at least the 396Conqueror’s work was permanent and consonant with the strictest ecclesiastical ideas of the time.

We have already remarked that to the men of the eleventh century, ecclesiastical reform implied the general enforcement of clerical celibacy. The Winchester Council of 1072 had issued a decree against unchaste clerks, but the matter was not taken up in detail for four years more, and the settlement which was then arrived at was much more lenient to the adherents of the old order than might have been expected. It made a distinction between the two classes of the secular clergy. All clerks who were members of any religious establishment, whether a cathedral chapter, or college of secular canons, were to live celibate for the future. The treatment applied to the upland clergy was summary. It would have been a hopeless task to force the celibate life upon the whole parochial clergy of England, but steps could be taken to secure that the married priest would become an extinct species in the course of the next generation. Accordingly, parish priests who were married at the time might continue to live with their wives, but all subsequent clerical marriage was absolutely forbidden, and the bishops were enjoined to ordain no man who had not previously made definite profession of celibacy. In all this Lanfranc was evidently anxious to pass no decree which could not be carried into immediate execution, even if this policy involved inevitable delay 397before the English clergy in this great respect were brought into line with their continental brethren. The next century had well begun before the native clergy as a whole had been reduced to acceptance of the celibate rule.

The monastic revival which followed the Conquest told in the same direction. In the mere foundation of religious houses, the Conqueror’s reign cannot claim a high place. Such monasteries as derive their origin from this period were for the most part affiliated to some continental establishment. The Conqueror’s own abbey of St. Martin of the Place of Battle was founded as a colony from Marmoutier, though it soon won complete autonomy from the jurisdiction of the parent house. It was a noteworthy event when in 1076 William de Warenne founded at Lewes the first Cluniac priory in England, although it does not appear that any other house of this order had arisen in this country before 1087. In monastic history the interest of the Conqueror’s reign centres round the old independent Benedictine monasteries of England, and their reform under the administration of abbots imported from the continent. Here there was much work to be done; not only in regard to the tightening of monastic discipline, but also in the accommodation of these ancient houses, with their wide lands and large dependent populations, to the new conditions of society which were the result of the Conquest. Knight service had to be provided 398for; the property of the monastery had to be organised to enable it to bear the secular burdens which the Conqueror’s policy imposed; foreign abbots were at times glad to rely upon the legal knowledge which native monks could bring to bear upon the intricacies of the prevailing system of land tenure. The Conqueror’s abbots were often men of affairs, rather than saints; their work was here and there misunderstood by the monks over whom they ruled, yet it cannot be doubted that a stricter discipline, a more efficient discharge of monastic offices, a higher conception of monastic life, were the results of their government.

The influence of their work was not confined within monastic walls. In the more accurate differentiation of monastic duties which they introduced, they were not unmindful of the claims of the monastery school. Very gradually the schools of such houses as St. Albans and Malmesbury came to affect the mass of the native clergy. And the process was quickened by the control which the monasteries possessed over a considerable proportion of the parish churches of the country. The grant of a village to an abbey meant that its church would be served by a priest appointed by the abbot, and in Norman times no baron would found a religious house without granting to it a number of the churches situate upon his fief. Already in 1066 the several monasteries of England possessed a large amount of patronage; and the Norman abbots of the 399eleventh and twelfth centuries were not slow to employ the influence they possessed in this way for the elevation of the native clergy.

Of course, there is another side to this picture. In the little world of the monastery, as in the wide world of the state, it was the character of the ruling man which determined whether the ascendancy of continental ideas should make for good or evil. The autocracy of the abbot might upon occasion degenerate into sheer tyranny: there is the classical instance of Thurstan of Glastonbury, who turned a body of men-at-arms upon his monks because they resisted his introduction of the Ambrosian method of chanting the services.[292] It was an easy matter for an abbot to use the lands of his church as a means of providing for his needy kinsmen in Normandy[293]; the pious founder in the next generation would often explicitly guard against the unnecessary creation of knights’ fees on the monastic estates. An abbot, careless of his responsibilities, might neglect to provide for the service of the village churches affiliated to his house; and it would be difficult to call him to account for this. But, judging from the evidence which we possess, we can only conclude that the church in England did actually escape most of the evils which might have resulted from the superposition of a new 400spiritual aristocracy. The bad cases of which we have information are very clearly exceptions, thrown into especial prominence on this very account.

And against the dangers we have just indicated we have to set the undoubted fact that with the Norman Conquest the English church passes at once from a period of stagnation to a period of exuberant activity. In the conduct of the religious life, in learning and architecture, in all that followed from intimate association with the culture and spiritual ideals of the continent, the reign of the Conqueror and the primacy of Lanfranc fittingly inaugurate the splendid history of the medieval church of England. And it is only fair for us to attribute the credit for this result in large measure to King William himself. Let it be granted that the actual work of reform was done by the bishops and abbots of England under the guidance of Lanfranc; there will still remain the fact that the Conqueror chose as his spiritual associates men who were both willing and able to carry the work of reform into effect. Nothing would have been easier than for King William, coming in as he did by conquest, to treat the English church as the lawful spoils of war. Its degradation under the rule of feudal prelates of the type of Geoffrey of Coutances would have made for, rather than against, his secular autocracy. Had he reduced the church to impotence he would have spared 401his successors many an evil day. But, confident that he himself would always be supreme in church as well as state, he was content to entrust its guidance to the best and strongest men of whom he knew, and if he foresaw the dangers of the future he left their avoidance to those who came after him.

No detailed account can be given here of the prelates whom the Conqueror appointed to ecclesiastical office in England. In point of origin they were a very heterogeneous class of men. Some of them were monks from the great abbeys of Normandy; Gundulf of Rochester came from Caen, Remigius of Dorchester from Fécamp; others, such as Robert of Hereford, were of Lotharingian extraction. Under the Conqueror, as under his successors, service at the royal court was a ready road to ecclesiastical promotion; nor were the clerks of the king’s chapel the least worthy of the new prelates. Osmund of Salisbury, who attained to ultimate canonisation, had been chancellor from 1072 to 1077. But a question immediately presents itself as to the relations which existed between these foreign lords of the church and the Englishmen, clerk and lay, over whom they ruled. Learned and zealous they might be, and yet, at the same time, remain entirely out of touch with the native population of England. To presuppose this, however, would be a great injustice to the new prelates. The very diversity of their origin prevented 402them from sharing the racial pride of the lay nobility, and their position as servants of a universal church told in the same direction. They learned the English language, and some at least among them preached to the country folk in the vernacular. They preserved the cult of the native saints, though they criticised with good reason the grounds on which certain kings and prelates had received canonisation, and in most dioceses they retained without modification the forms of ritual which had been developed by the Anglo-Saxon church. Among all the forces which made for the assimilation of Englishman to Norman in the century following the Conquest the work of King William’s bishops and abbots must certainly hold a high place.

The friendly relations which had existed between William and the Curia during the pontificate of Alexander II. were not interrupted immediately by the accession of Hildebrand, in 1073, but there soon appeared ominous symptoms of coming strife. It was no longer a matter of vital importance for William to retain the favour of the papacy—he was now the undisputed master of England and Normandy alike. Hildebrand, a man of genius, in whose passionate character an inherent hatred of compromise clashes with a statesmanlike recognition of the demands of practical expediency, could not be expected to refrain from advancing the ecclesiastical claims to the furtherance of which his whole soul was 403devoted. The Conqueror had indeed gone far in the work of reform, but neither in England nor in Normandy did he show any intention of conforming to the Hildebrandine conception of the model relationship which should exist between church and state. Of his own will he appointed his bishops and abbots, and they in turn paid him homage for their temporal possessions; he controlled at pleasure the intercourse between his prelates and the Holy See. Herein lay abundant materials for a quarrel; the wonder is that it did not break out for six years after Hildebrand’s succession.

The immediate cause of the outbreak was the abstention of the English and Norman bishops from attendance at the general synods of the church which Hildebrand convened at Rome during these years. Lanfranc was the chief offender in this respect, but before long Hildebrand came to recognise that Lanfranc was only acting in obedience to his master’s orders, and anger at the discovery drove the Pope to take the offensive against his former ally. Lanfranc was peremptorily summoned to Rome; the archbishop-elect of Rouen, William Bona Anima, was refused the papal confirmation, and Archbishop Gebuin of Lyons was given an extraordinary commission as primate of the provinces of Rouen, Sens, and Tours; a step which at once destroyed the ecclesiastical autonomy of Normandy. William’s reply to this attack was 404characteristic of the man. He was not without personal friends at the papal court, and without yielding his ground in the slightest in regard to the main matter in dispute he contrived to pacify the angry Pope by protestations of his unaltered devotion to the Holy See. Gregory bided his time; Archbishop Gebuin’s primacy came to nothing. William of Rouen received the pallium, and shortly after these events the Pope is found writing an admonitory letter to Robert of Normandy, then in exile. The storm had in fact blown over, but a greater crisis was close at hand.

It is quite possible that Gregory considered that he had won a diplomatic victory in the recent correspondence. He had not, it is true, carried his main point, but he had drawn from the king of England a notable expression of personal respect, and it is possible that this emboldened him shortly afterwards to make a direct demand upon William’s allegiance. In the course of 1080, to adopt the most probable date, Gregory sent his legate Hubert to William with a demand that the latter should take an oath of fealty to the Pope, and should provide for the more punctual payment of the tribute of Peter’s Pence due from England. In making the latter demand Hildebrand was only claiming his rights; from ancient time Peter’s Pence had been sent to Rome from England, and the Conqueror admitted his obligation in the matter. But the claim of fealty stood on a different footing. William, 405indeed, cannot have been unprepared for it; it was inevitable that sooner or later the papacy would endeavour to obtain a recognition, in the sphere of politics, of its support of the Norman claims on England in 1066. None the less, it was entirely inadmissible from William’s standpoint. So far as our evidence goes, it is certain that William had made no promise of feudal allegiance in 1066[294]; for him, as indeed for Alexander II., the papacy had already reaped its reward in the ecclesiastical sphere, in the power of initiating the reform of the English church, in the more intimate connection established between Rome and England. Alexander II. had been willing to subordinate all questions of spiritual politics to the more pressing needs of ecclesiastical reform, and Gregory had hitherto followed his predecessor’s lead; nor on the present occasion did he do more than assert a claim of the recognition of which he can have held but slender hopes. For William repudiated the Pope’s demand outright, asserting that none of his predecessors had ever sworn fealty to any former Pope, nor had he ever promised to do the like. We have no information as to the reception which William’s answer met at Rome; but, whatever resentment he may have felt, Gregory was debarred by circumstances from taking offensive action against the king of England. In the very year of this correspondence, Gregory found himself confronted 406by an anti-pope, nominated by the emperor; and from this time onward, the Pope’s difficulties on the continent increased, up to the hour of his death in exile five years later. Fortune continued true to William, even in his ecclesiastical relations.

There is no need to trace in detail the history of William’s dealings with the church during his last years. In England the work of reform, well begun in the previous decade, continued without interruption under the guidance of the new prelates. There is some evidence, indeed, that towards the close of William’s reign the English clergy were in advance of their Norman brethren in strictness of life and regard for canonical rule; at least in 1080, at the Synod of Lillebonne,[295] the king found it necessary to assume for himself the jurisdiction over the grosser offences of the clergy, on the ground that the Norman bishops had been remiss in their prosecution. But in England the leaders of the church seem to have enjoyed the king’s confidence to the last, and their reforming zeal needed no royal intervention. The work of Dunstan and Oswald, frustrated at the time by unkind circumstances, had at last, under stranger conditions than any they might conceive, reached its fulfilment.

And Last updated on: Saturday, 04-Jan-2025 16:31:19 GMTTrying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content