Search london history from Roman times to modern day

The eventful life of the Conqueror was within two years of its close when he decreed the compilation of that record which was to be the lasting monument of his rule in England. It is probable that if due regard be paid to the conditions of its execution Domesday Book may claim to rank as the greatest record of medieval Europe; certainly it deserves such preference among the legal documents of England. For, while we admire the systematic treatment which the great survey accords to county after county, we must also remember that no sovereign before William could have had the power to draw such wealth of information from all England between the Channel and the Tees; and that the thousands of dry figures which are deliberately accumulated in the pages of Domesday represent the result of the greatest catastrophe which has ever affected the national history. Domesday Book, indeed, has no peer, because it was the product of unique circumstances. Other conquerors have been as powerful as William, and as exigent of their royal rights; no other conqueror has so consistently regarded himself as the strict successor of the native kings who were before him; above all, no other conqueror 458has been at pains to devise a record of the order of things which he himself destroyed, nor even, like William, of so much of it as was relevant to the more efficient conduct of his own administration. Domesday Book is the perfect expression of the Norman genius for the details of government.government.

It is needless to say that William had no intention of enlightening posterity as to the social and economic condition of his kingdom. His aim was severely practical. How it struck a contemporary may be gathered from that well-known passage in which the Peterborough chronicler opens the long series of commentaries on Domesday by recording his impressions of the actual survey:

“After this the king held a great council and very deep speech with his wise men about this land, how it was peopled and by what men. Then he sent his men into every shire all over England and caused it to be ascertained how many hundred hides were in the shire and what land the king had, and what stock on the land, and what dues he ought to have each year from the shire. Also he caused it to be written, how much land his archbishops, bishops, abbots, and earls had, and (though I may be somewhat tedious in my account) what or how much each land-holder in England had in land or in stock and how much money it might be worth. So minutely did he cause it to be investigated that there was not one hide or yard of land, nor even (it is shameful to write of it though he thought it not shameful to do it) an ox nor a cow or swine that was not set down in his writ. And all the writings were brought to him afterwards.”

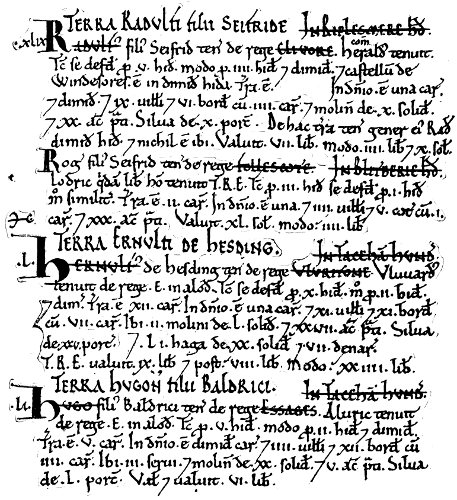

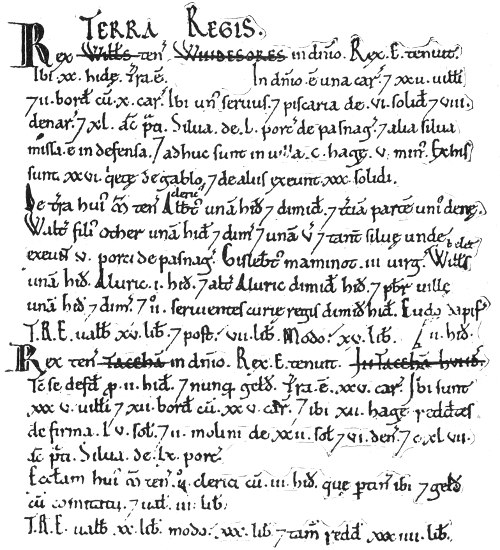

PORTION OF A PAGE OF DOMESDAY BOOK

(THE BEGINNING OF THE BERKSHIRE SECTION)

Opinion at Peterborough was clearly adverse to the survey, and Florence of Worcester tells us that the proceedings of the king’s commissioners caused riots in various parts of England. The exact scope of the information demanded by the commissioners cannot be better expressed than in the words of a writer belonging to the neighbouring abbey of Ely, who took an independent copy of the returns made to those officers concerning the lands of his monastery, and describes the nature of the inquiry thus:

“This is the description of the inquiry concerning the lands, which the king’s barons made, according to the oath of the sheriff of the shire and of all the barons and their Frenchmen and of the whole hundred-court—the priests, reeves and six villeins from every vill. In the first place [they required] the name of the manor; who held it in the time of King Edward, and who holds it now, how many hides [hidæ] are there, how many ploughs in demesne and how many belonging to the men, how many villeins, cottars, slaves, freemen and sokemen; how much woodland, meadow and pasture, how many mills and fisheries; how much has been added to or taken from the estate, how much the whole used to be worth, and how much it is worth now; and how much each freeman or sokeman had or has there. All this thrice over; with reference to the time of King Edward, and to the time when King William gave the land and to the present time; and if more can be got out of it than is being drawn now.”[321]

460Now, although the fact may not appear on a first reading of these passages, all these details were entirely subsidiary to one main object—the exact record of the local distribution of the king’s “geld” or Danegeld, the one great direct tax levied on the whole of England. Domesday is essentially a financial document; it is a noteworthy example of that insistence on their fiscal rights which was eminently characteristic of the Anglo-Norman kings, and was the chief reason why they were able to build up the strongest government in Western Europe. Every fact recorded in Domesday bears some reference, direct or indirect, to the payment of the Danegeld, for the king’s commissioners knew their business, and the actual scribes who arranged the results of the survey were remorseless in rejecting all details which did not fit into the general scheme of their undertaking. It should not escape observation that this fact prepares many subtle pitfalls for those who would draw a picture of English society based on the materials supplied by Domesday; but more of this will be said later, for there are certain questions of history and terminology which demand attention at the outset.

The most important of those points is the meaning of those “hides,” which are mentioned in both of the above extracts. This, indeed, is the essential clue to the interpretation of Domesday, and it is unfortunately very elusive, for the term can be traced back to a very early period of Anglo-Saxon 461history and more than one meaning came to be attached to it in the course of its long history. When we first meet the “hide,” the word seems to denote the amount of land which was sufficient for the support of a normal household; it is the average holding of the ordinary free man of Anglo-Saxon law. This much is reasonably certain, but difficulties crowd in upon us when we attempt to estimate the capacity of the hide in terms of acreage. Much discussion has arisen about this point, but we may say that at present there are two main theories on the subject, one assigning to the hide one hundred and twenty acres of arable land, the other some much smaller quantity, such as forty-eight or thirty acres, in either case with sufficient appurtenances in wood, water, and pasture for the maintenance of the plough and its oxen. Just now the prevailing view seems to be that the areal capacity of the hide may have varied from county to county—that, for instance, while we know that in the eleventh century the hide stood at one hundred and twenty acres in Cambridgeshire and Essex, it may not improbably have contained forty-eight acres in Wiltshire. Important, or rather vital, as is the question for students of Anglo-Saxon history, it does not concern us to quite the same extent, and we must pass on to a change which came over men’s conception of this tenement and intimately affects the study of Domesday.

Our normal free householder, the man who held 462a “hide” in the seventh century, was burdened with many duties towards the tribal state to which he belonged. He had to serve in the local army, the fyrd, to keep the roads and bridges in his neighbourhood in repair, to help to maintain the strong places of his district as a refuge in time of invasion, and to contribute towards the support of the local king or ealdorman. Out of these elements, and especially the last, was developed a rudimentary military and financial system which is recorded in certain ancient documents which have come down to us from the Anglo-Saxon period, and deserve our attention as the direct ancestors of Domesday Book. They may be described as a series of attempts to express, in terms of hides, the capacity of the several districts of England with which they deal, for purposes of tribute or defence. The eldest of these documents, which is now generally known as the Tribal Hidage,[322] is a record of which the date cannot be fixed within a century and a half, while very much of its text is quite unintelligible, but in form it is clear enough. It consists of a string of names with numbers of hides attached; thus, the dwellers in the Peak are assigned 1200 hides, the dwellers in Elmet 600, the Kentishmen 15,000, and the Hwiccas 7000. Now, it is obvious that all these are round numbers, as in fact are all the figures occurring in the document; and this is a point of considerable importance, for it implies that the 463distribution of hides recorded in this early list was a matter of rough estimate, rather than of computation, since we cannot suppose that there were just 1200 free householders in the Peak of Derbyshire, nor exactly 15,000 in Kent. These figures are intended to represent approximately the respective strength of such districts, and are expressed in even thousands or hundreds because numbers of this kind will be easy to handle, a practice which we can see to be inevitable, for a barbarian king of the time of Beda would be a very unlikely person to institute statistical inquiries as to the exact number of hides under his “supremacy.” But the point that concerns us is, as we shall see later, that the distribution of hides in Domesday, for all its appearance of statistical precision, is in reality just as much a matter of estimate and compromise as was the rough reckoning which is recorded in the Tribal Hidage.

These remarks apply equally to the next document in the series of fiscal records which leads up to Domesday. Probably in the reign of Edward the Elder, when Wessex was recovering from the strain of the great Danish invasion, some scribe drew up a list of strong places or “burhs,” mostly in that country, with the number of hides assigned to the maintenance of each, and here again we find round figures resembling those which we have noticed in the Tribal Hidage.[323] In this way 700 hides 464are said to belong to Shaftesbury, 600 to Langport, 100 to Lyng. Apparently the wise men of Wessex have decreed that an even number of hides, roughly proportional to the area to be defended, should be assigned to the upkeep of each of those “burhs,” and have left the men of each district to settle the incidence of burden among themselves. It will be seen that the system on which this document (which is conveniently called the “Burghal Hidage”) is based is much more artificial than that represented in the Tribal Hidage—in the latter we are dealing with “folks” or “tribes,” if the word be not expressed too strictly; here we have conventional districts, the extent of which is evidently determined by external authority. This being so, it becomes possible to make certain suggestive comparisons between the Burghal Hidage and Domesday Book. Thus the former assigns 2400 hides to Oxford and Wallingford, respectively, and 1200 to Worcester; and if we count up the number of hides which are entered in the Domesday surveys of Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Worcestershire, we shall find that in all three cases the total will come very near to the number of hides assigned to the towns which represent these shires in the Burghal Hidage; the correspondence being much too close to be the result of chance. Hence, if the distribution of hides in the Burghal Hidage is artificial, we should be prepared for the conclusion that the similar distribution in Domesday is artificial also.

465A century passed, and England was again being invaded by the Danes. In the vain hope of buying off the importunate enemy the famous Danegeld was levied, originally as an emergency tax, but one which was destined to be raised, at first sporadically, and then at regular intervals until the end of the twelfth century. This new impost must, one would suppose, have called for a re-statement of the old Hidages, but no such record has come down to us. On the other hand we possess a list of counties with their respective Hidages annexed, which is generally known as the “County Hidage,” and assigned to the first half of the eleventh century. This document[324] forms a link between the Burghal Hidage and Domesday; for, while it agrees with the older record in the figures which it gives for Worcestershire, Berkshire, and Oxfordshire, its estimate approximates very closely to the Domesday assessment of Staffordshire, Gloucestershire, and Bedfordshire.

And so we come to the Norman Conquest. At the very beginning of his reign, William, undeterred by the legend of his saintly predecessor, who had seen the devil sitting on the money bags, and had therefore abolished the Danegeld, laid on the people a geld exceeding stiff. At intervals during his reign a “geld” was imposed: in particular, in 1083, he raised a tax of seventy-two pence 466on the hide, the normal rate being only two shillings. It is not improbable that the grievance caused by this heavy tax may have been one chief reason why Domesday Book was compiled. We have seen enough to know that the system of assessment which underlies Domesday was, in principle at least, very ancient. It must have become very inequitable, for mighty changes had passed over England even in the century preceding the Conquest. We know that William had tried to rectify matters by drastic reductions of hidage in the case of individual counties, and it is by no means improbable that the Domesday Inquest was intended to be the preliminary to a sweeping revision of the whole national system of assessment. William died before he could undertake this, and so far as we know it was never attempted afterwards, for it has been pointed out that in 1194 the ransom of Richard I. was raised in certain counties according to the Domesday assessment.[325] This rigidity of the artificial old system makes its details especially worthy of study, for it is strange to see a fiscal arrangement which can be traced back to the time of Alfred still capable of being utilised in the days of Richard I. and Hubert Walter.

PORTION OF A PAGE OF DOMESDAY BOOK

(THE BEGINNING OF THE BERKSHIRE SECTION)

What, then, are the main features of this system? Much of its vitality, cumbrous and unequal as it was, may doubtless be ascribed to the fact 467that it was based on the ancient local divisions of the country, the shires, wapentakes or hundreds, and vills. Put into other words, the distribution of the hides which we find in Domesday is the result of an elaborate series of subdivisions. At some indefinitely distant date, it has been decreed that each county shall be considered to contain a certain definite number of hides, that Bedfordshire, for example, shall be considered to contain—that is, shall be assessed at—1200 hides. The men of Bedfordshire, then, in their shire court, proceeded to distribute these 1200 hides among the twelve “hundreds” into which the county was divided, paying no detailed attention to the area or population of each hundred, nor even, so far as can be seen, obeying any rule which would make a hundred answer for exactly one hundred hides, but following their own rough ideas as to how much of their total assessment of their county each hundred should be called upon to bear. The assessment of the hundreds being thus determined, the next step was to divide out the number of hides cast upon each hundred among the various vills of which it was composed, the division continuing to be made without any reference to value or area. And then the artificiality of the whole system is borne in upon us by the most striking fact—the discovery of which revolutionised the study of Domesday Book—that in the south and west of England the overwhelming majority of vills are assessed in some fraction 468or multiple of five hides.[326] The ubiquity of this “five-hide unit” is utterly irreconcilable with any theory which would make the Domesday hide consist of any definite amount of land; a vill might contain six or twenty real, arable hides, scattered over its fields, but, if it agreed with the scheme of distribution followed by the men of the county in the shire and hundred courts, that vill would pay Danegeld on five hides all the same. The Domesday system of assessment, then, was not the product of local conditions but was arbitrarily imposed from above. The hide was not only a measure of land, but also a fiscal term, dissociated from all necessary correspondence with fact.

But, before passing to further questions of terminology, it will be well to give some instances of the application of the “five-hide unit,” and, as Bedfordshire has been specially referred to above, we may take our examples from that county. Accordingly, if with the aid of a map we follow the course of the Ouse through Bedfordshire, we shall pass near to Odell, Risely, and Radwell, assessed at ten hides each; Thurghley and Oakley at five; Pavenham, Stagsden, Cardington, Willington, Cople, and Northill at ten; Blunham at fifteen; Tempsford at ten; Roxton at twenty; Chawston at ten; Wyboston at twenty, and Eaton Socon at 469forty. Thus, within a narrow strip of one county we have found seventeen instances of this method of assessment, and there is no need to multiply cases in point. On almost every page of the survey in which we read of hides, we may find them combined in conventional groups of five, ten, or the like.

Not all England, however, was assessed in hides; three other systems of rating are to be found in the country. In Kent, the first county entered in Domesday Book, a peculiar system prevailed in which the place of the hide was taken by the “sulung,” consisting of four “yokes” (iugera), and most probably containing two hundred and forty acres, thus equalling a double hide.[327] The existence of the sulung in Kent as a term of land measurement can be traced back to the time when that county was an independent kingdom; the process by which the word came to denote a merely fiscal unit was doubtless analogous to the similar development which we have noticed in the case of the “hide.” Taken in conjunction with the singular local divisions of Kent, and with the well-known peculiarities of land tenure found there, this plan of reckoning by “sulungs” instead of hides falls into place as a proper survival of the independent organisation of the county.

Another ancient kingdom also preserves an unusual form of assessment in Domesday. In East Anglia we get for once a statement in arithmetical 470terms as to the amount which each vill must contribute to the Danegeld. Instead of being told that there are, say, five hides in a vill, and being left to draw the conclusion that that vill must pay ten shillings or more according to the rate at which the Danegeld is being levied on the hide, we are given the amount which each vill must pay when the hundred in which it is situated pays twenty shillings. This form of sliding scale is unknown outside Norfolk and Suffolk, and is even more obviously artificial than the assessment of other counties. Each hundred in East Anglia seems to have been divided into a varying number of “leets,”—and it has been suggested that each leet had to pay an equal amount towards the Danegeld due from the hundred,[328] but the assessment of East Anglia in other respects presents some special difficulties of its own, although they cannot be discussed here.

Of much greater importance is the remaining fiscal unit to be found in Domesday. In Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, and Rutland all assessments are expressed in “carucates,” instead of hides, each carucate being composed of eight bovates, and each bovate containing, as is probable, fifteen (fiscal) acres. This distinction was remarked on in the twelfth century by Hugh “Candidus,” the historian of Peterborough, who says, “In Lincolnshire there 471are no hides, as in other counties, but instead of hides there are carucates of land, and they are worth the same as the hides.” It is evident that by derivation at least the Domesday carucata terræ must originally have meant a ploughland, that is, the amount of land capable of being tilled in one year by the great plough-team of eight oxen, according to whatever system of agriculture may have then been current, and it is equally certain that the word “bovate” takes its derivation from the ox. But, just like the hide, the carucate, from denoting a measure of land, had come to mean an abstract fiscal quantity, subject to the same conditions of distribution as affected the former unit. This is proved by the fact that the carucates are found combined in the above counties into artificial groups according to exactly the same principle as that which determined the distribution of hides in the south, with one highly curious variation in detail. Whereas we have seen that in the south and west vills are nominally assessed at some multiple of five hides, in the north-eastern counties, with which we are now concerned, the prevailing tendency is for the vills to be rated at some multiple or fraction of six carucates. Put in another way: the assessment of the south and west was decimal in character, that of the north and east was duodecimal; while we should expect a Berkshire vill to be rated at five, ten, or fifteen hides, we must expect to find a Lincolnshire vill standing at six, twelve, or 472eighteen carucates.[329] We have in this way a “six-carucate unit,” to set beside and in distinction to the “five-hide unit,” which we have already considered.

Now, these details become very significant when we consider the geographical area within which these carucates are found combined after this fashion. The district between the Welland and the Tees has a historical unity of its own. As was the case with East Anglia and Kent, fiscal peculiarities are accompanied in this quarter also by a distinctive local organisation. The co-existence in this part of England of “Danish” place-names with local divisions such as the wapentake, which can be referred to northern influence, has always been considered as proving an extensive Scandinavian settlement to have taken place there; and we can now reinforce this argument by pointing to the above fiscal peculiarities, which we know to be confined to this quarter and which are invaluable as enabling us to define with certainty the exact limits of the territory which was actually settled by the Danes in the tenth century. In Denmark itself we find instances of the employment of a duodecimal system of reckoning similar to that on which we have seen the Domesday assessment of the above north-eastern counties to be based; and we may recognise in the 473latter the equivalent of the territory of the “Five Boroughs” of Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, and Stamford, together with the Danish kingdom of Deira (Yorkshire), across the Humber.

Tedious as these details may well seem, the conclusions to which they lead us are by no means unimportant. In the first place, we see how such ancient kingdoms as Kent, East Anglia and Deira, to which we may add the territory of the Five Boroughs, preserved in their financial arrangements many relics of their former independent organisation long after they had lost all trace of political autonomy. And then in the second place we obtain a glimpse into the principles which governed the policy of the Norman rulers of England towards native institutions. These were not swept away wholesale; centralisation was only introduced where it was absolutely necessary, and so long as local arrangements sufficed to meet the financial needs of the crown, they were not interfered with. Here, as elsewhere, it was not the policy of William or of his successors to disturb the ancient organisation of the country, for it could well be adapted to the purposes of a king who was strong enough to make his government a reality over the whole land, and in this respect the Conqueror and his sons need have no fear.

In the above account we have considered the Domesday system of assessment in its simplest possible form, but certain complications must now 474receive notice. In the first place the plan on which the survey itself is drawn up places difficulties in our way, for it represents a kind of compromise between geographical and tenurial principles. Thus, each county is entered separately in Domesday, but within the shire all estates are classified according to the tenant-in-chief to whom they belonged, and not according to the hundred or other local division in which they are situated. This is a fact to which we shall have again to refer, but it will be evident that more than one tenant-in-chief might very well hold land in the same vill, and this being the case, we can never be sure, without reading through the entire survey of a county, that we have obtained full particulars of any single vill contained in it. In other words, vill and manor were never of necessity identical, and in some parts of England, especially the north and east, such an equivalent was highly exceptional. In this way, therefore, in the all-important sphere of finance, the lowest point to which we can trace the application of any consistent principle in the apportionment of the “geld” was not the manor, but the vill; and accordingly before we can discover the presence of those five-hide and six-carucate units, which have just been described, we have often to combine a number of particulars which, taken individually, do not suggest any system at all. Two instances, one from Cambridgeshire and one from Derbyshire, will be in point here:

| Hides. | Virgates. | Acres. | |

| The King | 7 | 1 | |

| Picot the Sheriff | 4 | 3 | |

| Count Alan | 1 | ½ | |

| ” ” | ½ | ||

| Geoffrey de Mandeville | 5 | 0 | |

| Guy de Reinbudcurt | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Count Alan | 12 | ||

| 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Carucates. | Bovates. | |

| Henry de Ferrers | 3 | |

| Geoffrey Alselin | 1 | |

| Gilbert de Gand | 2 | 0 |

| Roger de Busli | 3 | 0 |

| ” ” | 4 | |

| 6 | 0 |

These examples show very clearly that no consistent principle governed the assessment of a fractional part of vills, and are typical of the neatness with which unpromising figures combine into even totals. As to the way in which the men of a vill apportioned their fiscal responsibility, we are left almost entirely in the dark; the vill or township seems to have had no court of its own capable of deciding such a matter. Largely, no doubt, it 476was a matter of tradition; a certain holding which had once answered for two hides would continue to do so, no matter into whose hands it might come, unless the assessment of the whole vill were arbitrarily raised or lowered from without, when the assessment of this particular parcel of land would almost automatically be affected in proportion. But these local matters do not come within the scope of our slender stock of early fiscal authorities, and so we hear nothing about them.

We are now in a position to examine a normal entry from Domesday Book in the light of the above conclusions. A Nottinghamshire manor will do very well:

“M[anor]—In Hoveringham Swegn had two carucates of land and two bovates assessed to the geld. There is land for four ploughs. There Walter [de Aincurt] has in demesne two ploughs, and five sokemen on three and a third bovates of this land, and nine villeins and three bordars who have four ploughs. There is a priest and a church and two mills rendering forty shillings, and forty acres of meadow. In King Edward’s time it was worth £4; now it is worth the same and ten shillings more.”

We ought first to see how each detail here fits into the general scheme of the survey. The statement as to the former owner of the manor was important; for, just as King William maintained that he was the lawful successor of King Edward, so also he was determined that each of his men 477should occupy in each manor which he might hold the exact legal position filled by the Englishman or group of Englishmen, as the case might be, whom he had dispossessed in that particular estate. In particular it was essential that he should take up his predecessor’s responsibility with reference to the “geld” due from his land, a point which is well brought out in the above entry, for Walter de Aincurt clearly is being debited with the same number of carucates and bovates as were laid to the account of “Swegn” before the Conquest. Probably fiscal in character also is the statement which follows, to the effect that in Hoveringham “there is land for four ploughs.” For all its apparent simplicity, this formula, which is extremely common in the survey, presents upon investigation an extraordinary number of difficult complications. Taken simply it would seem to denote the number of ploughs which could find employment on the manor, and most probably it has such an agricultural significance in many counties, the argument in the mind of the commissioners being: if this estate has land for more ploughs than are actually to be found there, it is undeveloped, and more “geld” may be got out of it some day; if it is being cultivated to the full extent of its areal capacity or in excess of it (for this often happens) its assessment probably represents its agricultural condition well enough, and it may therefore stand. By making this inquiry about “ploughlands” the commissioners are probably fulfilling the instruction 478which directed them to find out whether the king was drawing the largest possible amount from each manor, but great caution is needed before we decide that they are obtaining this information in quite the same way from every county surveyed. In one county, for example, the jurors may be stating the amount of land in their manor which has never been brought under the plough at all; in another we may be given the total number of ploughs, actual and potential, which could be employed in the estate; in yet a third the commissioners may have taken as an answer a statement of the number of ploughs that had been going in the time of King Edward. The commissioners are not in the least concerned with details about ploughs and ploughlands merely as such; their interest is entirely centred in a possible increase of the king’s dues from each manor surveyed. But it is well to remember this fact, for it throws most serious difficulties in the way of any estimate of the agricultural condition of England in the eleventh century.

More straightforward are the details which follow in our entry. It will be seen that the scribes have marked a distinction between three divisions of the land of the vill: first the lord’s demesne, then the land held of him by sokemen, then the holdings of the villeins and bordars. That such a distinction should be made was in accordance with the instruction given to the commissioners by which they were directed to find out not only 479how many ploughs were in demesne and on the villeins’ land respectively, but also how much each free man and sokeman in the manor possessed. These latter are so entered, not necessarily because they were more definitely responsible for their share of the manorial Danegeld[332] than were the villeins and bordars for their own portion, but largely no doubt because they were less directly under manorial control. We have seen that the sokemen and free men of Domesday most probably represent social classes which have survived the Conquest, and are rapidly becoming modified to suit the stricter conditions of land tenure which the Conquest produced. But in Domesday the process is not yet complete; the sokeman is still a somewhat independent member of the manorial economy, and as such it is desirable to indicate exactly the place which he fills in each estate. But that this part of the inquiry was not essential is proved by the fact that the holdings of the sokemen, whether in ploughs or land, are usually combined with those of the villeins and bordars, even in the surveys of the eastern counties, where the free population was strongest.

The communistic system of agriculture is sufficiently well brought out in this entry; the four plough teams which the men of Hoveringham possessed, so far as we can see, were composed of oxen supplied by sokemen, villeins, and bordars 480alike, and the survey is not careful to tell us what proportion of the thirty-two oxen implied in these teams was supplied by each of the above three classes. We should beware of the assumption that the sokemen of Domesday were invariably wealthier than the villeins; we know little enough about the economic position of either class, but we know enough to see that many a sokeman of the Conqueror’s time possessed much less land than was considered in the thirteenth century to be the normal holding of a villein. In the entry we have chosen we can see that the average number of oxen possessed by each man in the vill is something under two; and we may suspect that the three bordars owned no oxen, at all; but although the possession of plough oxen may here and there have been taken as a line of definition between rural classes, we cannot be sure that this is so everywhere, certainly we cannot assume that it is the case here.[333]

After its enumeration of the several classes of peasantry, with their agricultural equipment, the survey will commonly proceed to deal with certain incidental sources of manorial revenue; in the present case the church, the mills, and the meadow. Even in the eleventh century the relations between the lord of a manor and the church on his estate 481bear a proprietary character; the lord in most cases possesses the right of advowson and he can make gifts from the tithes of his manor to a religious house for the good of his individual soul. The village church and the village mill were both in their several ways sources of profit to the lord, and in the case we have chosen it will be noted that nearly half the value assigned to the manor by the Domesday jurors is derived from the proceeds of the latter. “Mill soke,” the right of the lord to compel his tenants to grind their corn at his mill, long continued to be a profitable feature of the manorial organisation. The peculiar value of the meadow lay in the necessity of providing keep for the plough-oxen over and above the food which they obtained by grazing the fallow portion of the village lands. The distribution of meadow land along the rivers and streams of a county determines to a great extent the relative value of the vills contained in it.[334]

The value which is assigned to a manor in Domesday Book seems to represent, as a general rule, a rough estimate of the rent which the estate would bring in to its lord if he let it on lease, stocked as it was with men and cattle. In general it is probable that the jurors were required to make such an estimate with regard to three periods, namely, 1066, 1086, and the time when King William gave the manor to its existing owner. The last estimate, however, is frequently 482omitted from the completed survey; but it is included often enough for us to be able to say that the disorder which attended the Conquest was commonly accompanied by a sharp depreciation in the value of agricultural land; and in many counties manorial values in general had failed to rise to their pre-Conquest level in the twenty years between 1066 and 1086. If the whole of England be taken into account, it has been computed that the average value of the hide or carucate will be very close to one pound, and the Nottinghamshire manor we are considering is sufficiently typical in this respect. But it must be remembered that the jurors on making their estimate of value would certainly have to take into consideration sources of local revenue which were not agricultural in character, and the tallage of the peasantry and the profits of the manorial court will be included in one round figure, together with the value of the labour services of the villeins and the rent of mills and meadows.

Our attempt to understand the terms employed in a typical entry may serve to introduce us to a matter of universal importance, the indefiniteness of Domesday. We are not using this word as a term of reproach. The compilers of Domesday had to deal with a vast mass of most intractable material, and the marvel is that they should have given so splendid an account of their task. But for all that, it is often a most formidable business to define even some of the commonest terms used 483in Domesday. It has been shown, for instance, that the word manerium, which we can only translate by “manor,” was used in the vaguest of senses. It may denote one estate rated at one hundred hides, and another rated at eighty acres; most manors will contain a certain amount of land “in demesne,” but there are numerous instances in which the whole manor is being held of a lord by the peasantry; in the south of England the area of a manor will very frequently coincide with that of the vill from which it takes its name, but then again there may very well be as many as ten manors in one vill, while a single manor may equally well extend over half a dozen vills. In many cases the vague impression left by Domesday is due to the indefiniteness of its subject-matter—if we find it hard to distinguish a free man from a sokeman this is in great measure due to the fact that these classes in all probability did really overlap and intersect each other. Just so if we cannot be quite sure what the compilers of our record meant when they called one man a “bordar” and another man a “villein,” we must remember that it would not be easy to give an exact definition of a “cottager” at the present day; and also that the villein class which covered more than half of the rural population of England cannot possibly have possessed uniform status, wealth, privileges, and duties over this vast area. But there exists another cause of confusion which is solely due to the idiosyncrasies of the Domesday 484scribes, and that is their inveterate propensity for using different words and phrases to mean the same thing. Thus when they wish to note that a certain man could not “commend” his land to anybody, without the consent of his lord, we find them saying “he could not withdraw without his leave,” “he could not sell his land without his leave,” “he could not sell his land,” “he could not sell or give his land without his leave”—all these phrases and many others describing exactly the same idea. This peculiarity runs through the whole of the survey; it is shown in another way by the wonderful eccentricities of the scribes in the matter of the spelling of proper names. So far as place names go, this variety of spelling does little more than place difficulties in the way of their identification; but when we find the same Englishman described in the same county as Anschil, Aschil, and Achi,[335] matters become more serious. For there is hardly a question on which we could wish for more exact evidence than that of the number of Englishmen who continued to hold land after the Conquest; and yet, owing to the habits of the Domesday scribes, we can never quite avoid an uneasy suspicion that two Englishmen whose names faintly resemble each other may, after all, turn out to be one and the same person. We cannot really blame the scribes for relieving their monotonous task by indulging in such pleasure as the variation of phrase and spelling 485may have brought them, but it is very necessary to face this fact in dealing with any branch of Domesday study, and the neglect of this precaution has led many enquirers into serious error.

Closely connected with all this is the question of the existence of downright error in Domesday Book itself. To show how this might happen, it will be necessary to give a sketch of the manner in which the great survey was compiled. “The king,” says the Anglo-Saxon chronicler, “sent his men into every shire all over England.” We cannot be quite sure whether they went on circuit through the several hundreds of each shire or merely held one session in its county town[336]; in either case there appeared before them the entire hundred court, consisting, as we have seen, of the priest, the reeve, and six villeins from every vill. But out of this heterogeneous assembly there seems to have been chosen a small body of jurors who were responsible in a peculiar degree for the verdict given. We possess lists of the jurors for most of the hundreds of Cambridgeshire, from which it appears that eight were chosen in each hundred, and, a very important point, that half of them were Frenchmen and half were Englishmen. Thus the commissioners obtained for each hundred the sworn verdict of a body of men drawn from both races and representing, so far as we can see, very different levels of society. We cannot 486assume that precisely the same questions were put to the jurors in every shire. The commissioners may well have been allowed some little freedom of adapting the form of the inquiry to varying local conditions, and the terminology of their instructions may have differed to some extent according to the part of England in which they were to be carried out; but the similarity of the returns obtained from very distant counties proves that the whole Domesday Inquest was framed according to one general plan. It is more likely that the differences which undoubtedly exist at times between the surveys of different counties are really due to the procedure of the scribes who shaped the local returns into Domesday as we possess it.[337]

It will be evident that the completed returns from each county must have consisted of a series of hundred-rolls arranged vill by vill according to the sequence followed by the commissioners in making the inquiry. The first task of the Domesday scribes was to substitute for the geographical order of the original returns a tenurial order based on the distribution of land among the tenants-in-chief in each shire. They must have worked through the returns county by county, collecting all the entries which related to land held by the same tenant-in-chief in each shire, and arranging 487them under appropriate headings, and we know that they paid no very consistent regard to local geography in the process. Where a vill was divided between two or more tenants-in-chief the division must have been marked by the jurors of its hundred in making their report; but, whereas the unity of the vill as a whole was respected in the original returns, it was disregarded by the Domesday scribes, for whom the feudal arrangements of the county were the first consideration. The first step to be taken in drawing a picture of the condition of any county surveyed in Domesday is the collection of their scattered entries and the reconstruction of the individual vills in their entirety. As any one who has attempted this exercise can testify, the risk of error is very great, and we may be sure that it was no less for the Domesday scribes themselves. We cannot often test the accuracy of Domesday by a comparison with other documents, but the few cases where this is possible are enough to destroy all belief in the literal infallibility of the great record. The work was done under great pressure and against time, and we should not cavil at its incidental inaccuracies.

Domesday Book as we possess it consists of two volumes, the second, known as Little Domesday, dealing with Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk, the first containing the survey of the rest of England. The two volumes are very different in plan and treatment. In Essex and East Anglia, the scribes 488have followed as nearly as possible the directions which we have quoted on page 458. They enumerate the live-stock on the several estates with an abundance of detail which quite justifies the complaint of the Peterborough Chronicler that there was not an ox or a cow nor a swine that was not set down in the king’s writ. It is from the survey of these counties also that we draw the great body of our information about the different sorts and conditions of men, their tenurial relations and personal status. But this wealth of detail is accompanied by considerable faultiness of execution, and in the first volume of Domesday the plan is different. In compiling Great Domesday the scribes abandoned the idea of transcribing the original returns in full, and contented themselves with giving a précis of them; the details which had been collected about sheep and horses are jettisoned and the whole survey is drawn within closer limits. The most reasonable explanation of this change is that the so-called second volume of Domesday represents the first attempt at a codification of the returns[338]; that the result was found too detailed for practical purposes, and that the conciser arrangement of the first volume was adopted in consequence. The volume combining Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk contains 450 folios and even the Conqueror might have been appalled at the outcome of his survey if all the thirty counties of England were to be described 489on the same scale. Whatever the reason, the change is accompanied by a marked improvement in workmanship and practicability.

The “first” volume of Domesday contains 382 folios and its arrangement deserves notice. In regular course the survey proceeds across England from Kent to Cornwall; the first 125 folios of the volume are in fact the description of the earldom of Wessex. Next, starting again in the east, the counties between Middlesex and Herefordshire are described; to be followed by the survey of the north midland shires from Cambridgeshire to Warwick, still following due order from east to west. Warwick is followed by Shropshire, for Worcestershire belongs to Domesday’s second belt, and the rest of the survey progresses from west to east from Shropshire to Notts, Yorkshire and Leicestershire completing the tale. In general the boundaries of the counties are the same as at the present day, but portions of Wales are included in Gloucester, Hereford, and Berkshire; the lands “between Ribble and Mersey” form a sort of appendage to Yorkshire, and Rutland in 1086 has not yet the full status of a county. It is not quite easy to explain why Domesday stops short at the Tees and the Ribble. Cumberland and Westmoreland were indeed reckoned parts of the Scotch kingdom at this time, but Northumberland and Durham were undoubtedly English. Possibly they had been too much harried in recent years to be worth the labour of surveying; possibly in that wild 490and lawless land an attempt to carry out the survey would have led to something more than local riots. At any rate Domesday’s omission is our loss, for it is in the extreme north that the old English tenures lingered the longest; we could wish for a description of them in the Conqueror’s day and conceived on the same plan as the full accounts which we possess of the feudalised south.

All over England the scribes so far as was possible followed a consistent plan in the arrangement of the returns for each county. The case of Oxfordshire will do for a typical instance. Here, as in nearly every shire to the north of the Thames, the county town is surveyed first; the interesting description which is given of Oxford filling a column and a half. The rest of the folio is occupied by a list of all those in the county who held land in chief of the crown, arranged and numbered in the order in which their estates are entered in the body of the survey. The scale of precedence adopted by the compilers of Domesday deserves remark, for it is substantially the same as the order which we find observed in the lists of witnesses to solemn charters of the time. First comes the king in the case of every county in which he held land. Then comes the body of ecclesiastical tenants holding of him within the shire, archbishops first, then bishops, then abbots, or rather abbeys, for the tendency is to assign the lands belonging to a religious house to the foundation itself rather than to its head. 491Among laymen the earls come first, foreign counts being placed on a level with their English representatives, the same Latin word (comes) expressing both titles. Then come the various “barons” undistinguished by any mark of rank, who of course form the larger number of the tenants-in-chief in any shire, and lastly, in most counties, the holdings of a number of men of inferior rank are thrown together under one heading as “the lands of the king’s servants, sergeants, or thegns.” Returning to the case of Oxfordshire we find the king, as ever, first on the list. He is followed by the archbishop of Canterbury and the bishops of Winchester, Salisbury, Exeter, Lincoln, Bayeux, and Lisieux, who in turn are succeeded by the abbeys of Abingdon, Battle, Winchcombe, Préaux, the church of Saint Denis of Paris, and the canons of Saint Frideswide of Oxford. Earl Hugh of Chester stands first among laymen of “comital” rank, being followed by the counts of Mortain and Evreux, Earl Aubrey of Northumbria, and Count Eustace of Bologne. Then come the barons, twenty-three in number in Oxfordshire, whose order in the survey seems to be determined by no more subtle cause than a shadowy idea on the part of the scribes of grouping them according to the initial letter of their extra names. The list becomes a little miscellaneous towards the close; three great ladies appear: Christina, the sister of Edgar the Etheling; the Countess Judith, Waltheof’s widow; and a lady who is vaguely described 492as “Roger de Ivry’s wife,” bringing the total up to fifty-five. Then comes another baron, Hascuit Musard, an important Gloucestershire land-owner, whose Oxfordshire holding would seem to have been overlooked by the scribes, for it is squeezed in along the foot of two folios of the survey. He is followed by Turkill of Arden, an Englishman, who was powerful in Warwickshire but only held one manor in Oxfordshire, the description of which is succeeded by “the land of Richard Engayne and other thegns.” Richard Engayne was the king’s huntsman, and a Norman, as were many of his fellows, but about half the names entered under this comprehensive heading are unmistakably English and characteristically enough they are entered in a group after the members of the conquering race. The fifty-ninth and last heading in this varied list runs, “These underwritten lands belong to Earl William’s fee,” a formula which is explained by the fact that the manors surveyed under it had belonged to Earl William Fitz Osbern, who as we know had been killed in Flanders in 1071, while his son and heir had been disinherited in 1075. And so we see that, although the earl’s tenants had lost their immediate lord in consequence of his forfeiture, they were not recognised as holding in chief of the crown, but were kept apart in a group by themselves in anticipation of the later feudal practice by which the tenants of a great fief or honour in the royal hands were conceived 493of as holding rather of their honour than of the king himself.

In the present chapter we have mainly dealt with Domesday Book from its own standpoint as a fiscal register, but for the majority of the students its real value lies in the unique light which it throws upon legal and social antiquities and upon the personal history of the men of the Conquest. In these latter respects the different parts of the survey are by no means of equal value. The space assigned to each county in Domesday was determined solely by the caprice of the scribes; counties of approximately equal area are assigned very different limits of space in the record. Equally due to the action of the scribes is the amount of social and personal details, above the necessary minimum of fiscal information required, which is included in the description of each county. The surveys of Berkshire and Worcestershire, for instance, are many-sided records which throw light upon every aspect of the history of the times; while on the other hand for the counties of the Danelaw the fiscal skeleton of the record is left bare and arid; we get columns of statistics and little beside. The interest of Domesday of course is vastly increased when we are able to supplement its details with information derived from some other contemporary record; Buckinghamshire, for example, in which county there was no religious house in 1086, is at a disadvantage compared 494with Berkshire, where the local history of Abingdon Abbey fills in the outline of the greater record, and gives life to some at least of the men of whom the names and nothing more are written in its pages. Apart from this adventitious source of light, Domesday imparts some of its most precious information when recording a dispute between two tenants as to the possession of land, or noting new “customs,” tolls, and so forth, which have been introduced since the Conquest, for then we may look for some statement of local custom or some reconstruction of the “status quo ante conquestum.” And this leads naturally to the last division of our present subject—the legal theory which underlies Domesday Book.

It is abundantly plain from all our narratives of the Conquest that King William regarded himself, and was determined that he should be regarded, as the lawful successor of his cousin King Edward; he was the true heir by blood as well as by bequest. Unfortunately wicked men had usurped his inheritance so that he was driven to regain it by force and arms; the earl of Wessex had taken upon himself the title of king and the whole nation had acquiesced in his unlawful rule. But the verdict of battle had been given in William’s favour; he had been accepted as king by the great men of the realm, and he had been duly crowned; it would be no more than justice for him to disinherit every Englishman as such for his tacit 495or overt rebellion. Moreover even after he had been received as king his rebellious subjects in every part of the land had risen against him; they had justly forfeited all claim to his royal grace; their lands by virtue of these repeated treasons became at his absolute disposal. Some such ideas as these underlie that “great confiscation” of which Freeman considered Domesday to be essentially the record, and two all-important conclusions followed from them. The first is that the time of King Edward, that phrase which meets us on every page of Domesday, was the last season of good law in the land; should any man claim rights or privileges by prescription he must plead that they had been allowed and accepted under the last king of the old native line. Just as his subjects cried for “the law of King Edward” as the system of government under which they wished to live, so to the king himself these words expressed the test of legality to be applied to whatever rights claimed an origin anterior to his own personal grant. Rarely does Domesday refer to any of the kings before Edward; the Conqueror’s reign has already become the limit of legal memory; never, except by inadvertence, does it refer to the reign of Harold by name. And then in the second place he who would prove the lawful possession of his land must rely in the last resort upon “the writ and seal” of King William. The whole tenor of Domesday seems to imply that all Englishmen 496as such were held to have been disinherited by the result of the Conquest. Save for the lands of God and his Saints all England had become the king’s; the disposition he might make of his vast inheritance depended solely upon his own will. If he should please to allow to an Englishman the possession of his own or others’ lands, this was a matter of pure favour, and Thurkill of Warwick and Colswegn of Lincoln could put forward no other title than that which secured their fiefs to the Norman barons around them. But then comes in that principle which is above all distinctive of the Norman Conquest—if William stepped by lawful possession into the exact position of the native kings who were before him, so each of his barons in each of his estates must be the exact legal successor, the “heir,” of the Englishman whom he supplanted. The term used by Domesday to express the relationship of the old and the new landlord is very suggestive: the Englishman is the Norman’s antecessor, a word which we only translate inadequately by the colourless “predecessor.” We are probably right in calling the Norman Conquest the one catastrophic change in our social history, but the change as yet was informal; it went on beneath the surface of the law; the terminology of Domesday testifies to the attempt to bring the social conditions of 1086 under formulas which would be appropriate to the time of King Edward. When we are told 497that there were ten manors in such a vill in the time of King Edward, or that there used to be twenty villeins in a certain manor but now there are only sixteen, we may gravely doubt whether the terms “manor” and “villein” were known in England before the Conquest, and yet we may recognise that the employment of these words in relation to the Confessor’s day is of itself very significant. King William as King Edward’s lawful heir wishes consistently to act as such so far as may be; his scribes in their terminology affect a continuity of social history, which does not exist.

Perhaps nothing could be more illustrative of these principles than a few extracts taken from the Lincolnshire “Clamores”—the statement of the various disputed claims which had come to light in the course of the survey, and the record of their settlement by the Domesday jurors. The following are taken at random in the order in which they are entered in Domesday:

“Candleshoe wapentake says that Ivo Taillebois ought to have that which he claims in Ashby against Earl Hugh; namely one mill and one bovat of land, although the soke belongs to Grainham.

“Concerning the two carucates of land which Robert Dispensator claims against Gilbert de Gand in Screnby through Wiglac, his predecessor [antecessor], the wapentake says that the latter only had one carucate, and the soke of that belonged to Bardney. But Wiglac forfeited that land to his lord Gilbert, and so 498Robert has nothing there according to the witness of the Riding.

“In the same Screnby Chetelbern claims one carucate against Gilbert de Gand through Godric [but the jurors], say that he only had half a carucate, and the soke of that belonged to Bardney, and Chetelbern’s claim is unjust according to the wapentake, because his predecessor forfeited the land. The men of Candleshoe wapentake with the agreement of the whole Riding say that Siwate and Alnod and Fenchel and Aschel equally divided their father’s land among themselves in King Edward’s time, and held it so that if there were need to serve with the king and Siwate could go the other brothers assisted him. After him the next one went and Siwate and the next assisted him and so on with regard to all, but Siwate was the king’s man.”

In these passages the actual working of the Domesday Inquest is very clearly displayed. In the first place we see that all really turns on those ancient local assemblies the wapentake and hundred courts. Not only do they supply the requisite information through the representative jurors to the commissioners, but it is by their verdict that the latter are guided in their pronouncements upon disputed claims. If Ivo Taillebois receives his seisin of that mill and oxgang of land in Ashby it will be because the wapentake court of Candleshoe has assigned it to him rather than the earl of Chester. This simple procedure has a great future before it; if the king can compel the local courts to give a sworn verdict to his officers, 499so in specific cases he can of his grace permit private persons to use these bodies in the same way. The Domesday Inquest is the noble ancestor of the Plantagenet “assizes,” and through them, by direct descent, of the jury in its perfected form. But the action of the local courts becomes doubly significant when we remember their composition. The affairs of the greatest people in the land, of the king himself, are being discussed by very humble men, men, as we have seen, carefully chosen so as to represent Frenchmen and Englishmen alike. Nothing is a more wholesome corrective of exaggerated ideas as to the severance and hostility of the two races than a due remembrance of the part which both played in the Domesday Inquest.

Equally important is the respect which is clearly being paid in the above discussions to the strict forms of law, of English law in particular. No very knotty problems arise in the course of our simple extract, but we can see that a Norman baron will often have to stand or fall in his claim according to the interpretation of some old English legal doctrine. We know from other sources that the intricacies of the rules which in King Edward’s time determined the rights and status of free men became a thing of wonder to the men of the twelfth century, and we may suspect that the Domesday commissioners were frequently tempted to cut these obsolete knots. But so far as is practicable, they are maintaining that the Norman must succeed to just the legal position of 500his English “antecessor”; Robert the Dispensator cannot claim the land which has been forfeited by Wiglac to Gilbert de Gand.

Lastly, one is always tempted to forget that twenty years had passed between the death of King Edward and the making of the Domesday Survey. Our attention is naturally and rightly concentrated on the great change which substituted a Norman for an English land-holding class, so that we are apt to ignore the struggles which must have taken place among the conquerors themselves in the division of the spoil; struggles none the less real because, so far as we can see, they were carried on under the forms of law. Death and confiscation had left their mark upon the Norman baronage; the personnel of Domesday Book would have been very different if the record had been drawn up a dozen years earlier. But, even apart from this, it was inevitable that friction should arise within the mass of Norman nobility as it settled into its position in the conquered land. The Domesday Inquest afforded a grand opportunity for the statement and adjustment of conflicting claims, and examples may generally be found in every few pages of Domesday Book.

The last point in connection with the survey which calls for special notice is the origin of the name by which it is universally known. “Domesday Book” is clearly no official title; it is a popular appellation, of which the meaning is not quite 501free from doubt. Officially, the record was known as the “Book of Winchester,” from the city in which it was kept; it was cited under that name when the abbot of Abingdon, in the reign of Henry I., proved by it the exemption of certain of his estates from the hundred court of Pyrton, Oxfordshire. The best explanation of its other, more famous name may be given in the words of Richard Fitz Neal, writing under Henry II.:

“This book is called by the natives, ‘Domesdei,’ that is by a metaphor the day of judgment, for as the sentence of that strict and terrible last scrutiny may by no craft be evaded, so when a dispute arises concerning those matters which are written in this book, it is consulted, and its sentence may not be impugned nor refused with safety.”[339]

On the whole this explanation probably comes near the truth. We may well believe that to the common folk of the time, this stringent, searching inquiry into their humble affairs may have seemed very suggestive of the last great day of reckoning. Viewed in this light the name becomes invested with an interest of its own; it is an abiding witness to the reluctant wonder aroused by the making of this, King William’s greatest work and our supreme record.

Penny of William I.

Penny of William I.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content