Search london history from Roman times to modern day

Catastrophic as the battle of Hastings seems to us now, in view of the later history, its decisive character was not recognised at once by the national party. The very incoherence of the Anglo-Saxon polity brought a specious advantage to the national cause, in that the defeat of one part of the nation by an invader left the rest of the country comparatively unaffected by the fact. The wars of Edmund Ironside and Cnut, fifty years before, show us groups of shires one after the other making isolated attempts to check the progress of the enemy, and few men could already have realised that the advent of William of Normandy meant the introduction of new processes of warfare which would render hopeless the casual methods of Anglo-Saxon generalship. Neither side, in fact, understood the other. William, on his part expecting that the total overthrow of the English king with his army would imply the immediate submission of the whole land, took up his quarters at Hastings on the day after the battle to receive the homage of all those Englishmen who might come in person to accept him as their lord. The passage of five days without a single surrender taught him that 212the fruits of victory would not fall into his hands without further shaking, and meanwhile the English nobility began to form plans for a continued resistance to his pretensions in the name of another national king.

Who that king should be was the first question which demanded settlement. There was no hope of preserving the English crown in the house of Godwine: the events of the past three weeks had been fatal to all the surviving sons of the old earl, with the exception of Wulfnoth the youngest, and he was most likely a prisoner or hostage in Normandy.[160] Harold’s one legitimate son was most probably as yet unborn; he had at least three illegitimate sons of sufficient age, but their candidature, if any one had suggested it, would certainly have been inacceptable to the churchmen on whom it rested to give ultimate sanction to any choice which might be made. Two alternatives remained: either a return might be made to the old West Saxon line in the person of Edgar the Etheling, or a new dynasty might be started again by the election of Edwin or Morcar. The one advantage which the former possessed, now as earlier in the year, was the fact that his election would not outrage the local particularism of any part of the country; it might not be impossible 213for Wessex, Mercia, and Northumbria to unite round him in a common cause. Nor was it unnatural that in this hour of crushing disaster men’s minds should involuntarily turn to the last male heir of their ancient kings. Apart from these considerations, there was something to be said in favour of the choice of one of the northern earls. It must have been clear that Mercia and Northumbria would have to bear the brunt of any resistance which might subsequently be made to the invader, whose troops were already occupying the eastern shires of the earldom of Wessex, and who would be certain before long to strike a blow at London itself. But the success of Harold’s reign had not been such as to invite a repetition of the experiment of his election. Edgar the Etheling was chosen king, and the two brother earls withdrew to Northumbria, imagining in their own minds, says William of Malmesbury, that William would never come thither.[161]

This motive gives an interest to their withdrawal which is lost if we regard it as a mere act of treachery to the national cause. There can be little doubt that what Edwin and Morcar intended was a partition of the kingdom between themselves and William, and it is at least questionable whether such a plan had not a better prospect of success than an attempt to recover the whole land for a king who had no personal qualities of leadership, and who could never hope to attach 214to himself any of that local sentiment in which lay the only real strength of the national party. The idea of a divided kingdom was by no means chimerical. Old men still living could remember the partition made by the treaty of Alney between Edmund Ironside and Cnut, and it was not a sign of utter folly for any man to suppose, within a week of the battle of Hastings, that William, having settled his score with Harold, might content himself with his rival’s patrimonial earldom of Wessex, leaving the north of England to its existing rulers. No one at this date could be expected to understand the extent to which William’s political ideas differed from those of Cnut; nor need we suppose that Edwin and Morcar were mistaken as to the reality, though they may have overestimated the military value, of the feeling for local independence in their two great earldoms. In the case of Northumbria, indeed, even after William’s presence had been felt in every part of the land, so acute an observer as Archbishop Lanfranc insisted on the subordination of the see of York to that of Canterbury on the ground that an independent archbishop of York might canonically consecrate an independent king of the Northumbrians.[162] What was lacking to the plan was not local separatism, but the skill and consistency of purpose which alone could turn it to account. Neither the ignominious 215failure of Edwin and Morcar, on the one hand, nor the grandiose phrases of chancery clerks about the “Empire of Britain,” on the other, should blind us to the fact that England was united only in name until the strong rule of its Norman lords had made the king’s word as truly law in Yorkshire as in Middlesex.

While the English leaders were disposing of their crown William was pursuing his deliberate course towards London by a route roughly parallel with the coast of Kent and Sussex. His delay at Hastings had not been time wasted; it allowed his troops to recover from the strain and excitement of the great battle, and it gave him the opportunity of receiving badly needed reinforcements from Normandy. On the 20th of October, six days after the battle, the second stage of the conquest began; William, with the main body of his army, moved out of Hastings, leaving a garrison in the newly built castle, and marched across the border of Kent to Romney. The men of the latter place had cut off a body of Norman soldiers who had landed there by mistake before the battle of Hastings; and the most famous sentence written by the Conqueror’s first biographer relates how William at Romney “took what vengeance he would for the death of his men.”[163] Having thus suggested by example the impolicy of resistance, a march of fifteen miles between the Kentish downs and the sea brought 216William to the greatest port and strongest fortress in south England, the harbour and castle of Dover. The foundation of the castle had probably been the work of Harold while earl of Wessex, and, standing on the very edge of the famous cliffs overhanging the sea, the fortress occupied a site which to Englishmen seemed impregnable, and which was regarded as very formidable by the Norman witnesses of this campaign.[164] The castle was packed with fugitives from the surrounding country, but its garrison did not wait for a formal demand for its surrender. Very probably impressed by what had happened on the previous day at Romney, they met William half way with the keys of the castle, and the surrender was duly completed when the army arrived at Dover. It was William’s interest and intention to treat a town which had submitted so readily as lightly as possible, but the soldiers, possibly suspecting that the booty of the rich seaport was to be withheld from them, got out of hand for once, and the town was set on fire. William attempted to make good the damage to the citizens, but found it impossible to punish the offenders as he wished, and ended by expelling a number of Englishmen from their houses, and placing members of his army in their stead.[165] Eight days were spent at Dover, during which the fortifications of the castle were brought up to an improved standard, and then William set out again “thoroughly to 217crush those whom he had conquered.” But before his departure he appointed the castle as a hospital for the invalided soldiers; for dysentery, which was set down at the time to over-indulgence in fresh meat and strange water, had played havoc with the army.[166]

With the surrender of Dover William’s communications with Normandy were firmly secured, and he now struck out directly towards his destined capital, along the Roman road which then, as at every period of English history, formed the main line of communication between London and the Kentish ports. Canterbury was the first place of importance on the way, and its citizens followed the prudent example of the men of Dover. Before William had gone far from Dover, the Canterbury men sent messengers who swore fealty to him, and gave hostages, and—an act which was a more unequivocal recognition of his title to the crown—brought him the customary payment due yearly from the city to the king. From this point, indeed, William had little reason to complain of the paucity of surrenders; the Kentishmen, we are told, crowded into his camp and did homage “like flies settling on a wound.”[167] But the even course of his success was suddenly interrupted. On the last day of October, he took up his quarters at a place vaguely described by William of Poitiers as the “Broken Tower,” and was there seized by a violent illness, which 218kept him for an entire month incapable of moving from the neighbourhood of Canterbury. But, if we can trust the chronology of our authorities, it was during this enforced delay that William received the submission of the capital of Wessex. Winchester at this time had fallen somewhat from its high estate under the West Saxon kings; along with certain other towns it had been given by Edward the Confessor to his wife Eadgyth as part of her marriage settlement, and it was now little more than the residence of the dowager queen. On this account, we are told that William thought it would be unbecoming in him to march and take the town by force and arms, so he contented himself with a polite request for fealty and “tribute.” Eadgyth complacently enough agreed, took counsel with the leading citizens, and added her gifts to those which were brought to William on behalf of the city.[168] This ready submission was a fact of considerable importance. Winchester lay off the track of an invader whose objective was London, and apart from his illness William could scarcely have afforded to part with a detachment of his small army sufficiently large to make certain the capture of the town. Yet the old capital was a most ancient and honourable city, containing the hall of the Saxon kings, in 219which probably were deposited the royal treasure and regalia; and its surrender with the ostentatious approval of King Edward’s widow was a useful recognition of William’s claim to be the true heir of the Saxon dynasty. In his dealings with Winchester the Conqueror’s example was followed by William Rufus, Henry I., and Stephen, though the paramount necessity for them of seizing the royal hoard at the critical moment of their disputed successions made them each visit the royal city in person.[169]

On his recovery, at or near the beginning of December, William resumed his advance on London. Doubtless Rochester made a peaceful surrender, but we have no information as to this, nor as to any further details of the long march until it brought the Conqueror within striking distance of London. London, it is plain, was prepared for resistance; and the narrow passage of the bridge, the only means of crossing the river at this point, made the city virtually impregnable from the south. William was not the man to waste valuable troops in a series of hopeless assaults when a less expensive method might prevail, and on the present occasion he merely sent out a body of five hundred knights to reconnoitre. A detachment of the English was tempted thereby to make a sally, but was driven back across the bridge with heavy loss, Southwark was burned to 220the ground,[170] and William proceeded to repeat the plan which had proved so successful in Maine three years before. Abandoning all attempt to take the city by storm, he struck off on a great loop to the west, and his passage can be traced clearly enough in Domesday Book by the devastation from which a great part of Surrey and Berkshire had not fully recovered twenty years afterwards. The Thames was crossed at last at Wallingford, and it was there that William received the submission of the first Englishman of high rank who realised that the national cause was doomed. Stigand, the schismatic archbishop of Canterbury, did homage and swore fealty, explicitly renouncing his allegiance to Edgar the Etheling, in whose ill-starred election he had played a leading part.[171] The weakness of Stigand’s canonical position, which was certain to be called in question if William should ever be firmly seated on the throne, made it advisable for him to make a bid for favour by an exceptionally early submission, and it was no less William’s policy graciously to accept the homage of the man who was at least the nominal head of the church in England. Probably neither party was under any misapprehension as to the other’s motives; but in being suffered to enjoy his pluralities and appropriated church 221lands for three years longer Stigand was not unrewarded for his abandonment of the national cause at the critical moment.

The exact time and place at which the remaining English leaders gave in their allegiance are rather uncertain. There is some reason, in the distribution of the lands which Domesday implies to have undergone deliberate ravage about this time, to suppose that, even when William was on the London side of the Thames, he did not march directly on the city, but continued to hold a north-easterly course, not turning southwards until he had spread destruction across mid-Buckinghamshire and south-west Bedfordshire. The next distinct episode in the process of conquest occurred at a place called by the Worcester Chronicle “Beorcham,” where allegiance was sworn to William on a scale which proved that now at last his deliberate policy had done its intended work, and that the party of his rival had fallen to pieces without daring to contest the verdict given at Hastings in the open field. Edgar the king-elect, and Archbishop Ealdred of York, with the bishops of Worcester and Hereford, and a number of the more important citizens of London “with many others met him [William], gave hostages, made their submission, and swore fealty to him.” And William of Poitiers tells us that when the army had just come in sight of London the bishop and other magnates came out, surrendered the city, and begged William 222to assume the crown, saying that they were accustomed to obey a king, and that they wished to have a king for their lord. One is naturally tempted to combine these two episodes, but this can only be done by abandoning the old identification of “Beorcham” with Great Berkhampstead, thirty miles from London, and by assuming the surrender to have taken place when the army appeared on the edge of the Hertfordshire Chilterns overlooking the Thames Valley, fifteen miles away, from the high ground of Little Berkhampstead near Hertford.[172]

Whatever the exact place at which the offer of the crown was made to William, it was straightway submitted by him to the consideration of the chiefs of his army. Two questions were laid before them: whether it was wise for William to allow himself to be crowned with his kingdom still in a state of distraction, and—this last rather a matter of personal feeling than of policy—whether he should not wait until his wife could be crowned along with him. Apart from these considerations, the assumption of the English crown was a step which concerned William’s own Normans scarcely less intimately than his future English subjects. The transformation of the duke of the Normans 223into the king of the English was a process which possessed a vital interest for all those Normans who were to become members of the English state, and William could not well do less than consult them on the eve of such a unique event. As to the ultimate assumption of the crown by William, no two opinions were possible: Hamon, viscount of Thouars, an Aquitanian volunteer of distinction, in voicing the sentiments of the army, began by remarking that this was the one object of the enterprise; but he went on to advocate a speedy coronation on the ground that were William once crowned king resistance to him would be less likely undertaken and more easily put down. With quite unintentional irony he added that the wisest and most noble men of England would surely never have chosen William for their king, unless they had seen in him a suitable ruler and one under whom their own possessions and honours would probably be increased. To guard against any wavering on the part of these “prudentissimi et optimi viri,” William immediately sent on a detachment to take possession of London and to build a castle in the city, while he himself, during the few days which had to pass before the Christmas feast for which he had fixed his coronation, devoted himself to sport in the wooded country of south Hertfordshire.[173]

Of the deliberations within London which led 224to this unconditional surrender on the part of the national leaders, we know little with any certainty, but it is not improbable that at some stage in his great march William had entered into negotiations with some of the chief men in the etheling’s party. Our most strictly contemporary account of these events[174] makes the final submission the result of a series of messages exchanged between the duke and a certain “Esegar” the Staller, on whom as sheriff of London and Middlesex fell the burden of providing for the defence of the city. We are given to understand that William sent privately to “Esegar” asking that he should be recognised as king and promising to be guided in all things by the latter’s advice. On receiving the message Esegar decided, rather unwisely, as the event proved, to try and deceive William; so he called an assembly of the eldest citizens and, laying the duke’s proposal before them, suggested that he should pretend to agree with it and thus gain time by making a false submission. We are not told the exact words of the reply which was actually sent, but we are informed that William saw through the plan and contrived to impress the messenger with his own greatness and the certain futility of all resistance to him to such an extent that the messenger on his return, by simply relating his experiences, induced the men of London to abandon the etheling’s cause straightway. The tale reads rather like an 225improved version of some simpler negotiations, but that is no reason for its complete rejection, and we may not unreasonably believe that, in addition to intimidating the city by his ravages in the open country, William tried to accelerate matters by tampering with some at least of those who were holding his future capital against him.

On Christmas day William was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey by Archbishop Ealdred of York, a clear intimation that Stigand’s opportunist submission would not avail to restore to him all the prerogatives of the primacy. The ceremony was conducted with due regard, as it would seem, to all the observances which had usually attended the hallowing of the Anglo-Saxon kings, only on the present occasion it was necessary to ask the assembled people in French as well as in English whether they would accept William as their king. The archbishop of York put the question in English, Geoffrey, bishop of Coutances, that in French, and the men of both races who were present in the Abbey gave a vociferous assent. Unfortunately the uproar within the church was misunderstood by the guard of Norman horsemen who were stationed outside, and they, imagining that the new subjects of their duke were trying to cut him down before the altar, sought to relieve his immediate danger by setting fire to the wooden buildings around,[175] and so creating a diversion. In this 226they were quite successful; amid indescribable confusion the congregation rushed headlong out of the church, some to save their own property, and some to take advantage of so exceptional an opportunity of unimpeded plunder. The duke and the officiating clergy were left almost alone; and in the deserted abbey William, quivering with excitement,[176] became by the ritual of unction and coronation the full and lawful successor of Alfred and Athelstan. But before the crown was placed upon his head the Conqueror swore in ancient words, which must have sounded ironical amid the noise and tumult, that he would protect God’s churches and their rulers, would govern all the people subjected to him with justice, would decree and keep right law, and would quite forbid all violence and unjust judgments.[177] And so the seal of the Church was set upon the work which had been in fact begun on that morning, three months before, when William and his army disembarked on the shore of Pevensey.

The disorder which had attended the coronation was actually the result of a misapprehension on the part of William’s own followers, but he evidently felt that the possibility of a sudden rising on the part of the rich and independent city was a danger which should not be ignored. Accordingly, to avoid all personal risk, while at the same time keeping in close touch with his capital, William 227moved from London to Barking, and stayed there while that most famous of all Norman fortresses, the original “Tower of London,” was being built. Most probably it was during this stay at Barking that William received the homage of such leading Englishmen as had not been present at the submission on the Hertfordshire downs. In particular Edwin and Morcar would seem to have recognised the inevitable at this time[178]; the coronation of William as king of all England by the metropolitan of York may have taught them that a division of the kingdom no longer lay within the range of practical politics. At any rate William did not think that it would be well for him to let them out of his sight for a season, and within a few days of the New Year they are found accompanying him as hostages into Normandy.

Our sole knowledge of the general state of the country at this most critical time comes from certain scattered writs which can be proved to have been issued during the few weeks immediately following the coronation. The information which they give is but scanty; they were of course not intended to convey any historical information at all, but they nevertheless help us to answer the important question how much of England had really submitted for the time to William’s rule by the end of 1066, and they do this in two ways. On the one hand, they were witnessed by some of the more important men, English as 228well as Normans, who were present in William’s court; on the other hand, we may safely acquit William of the folly of sending his writs into counties in which there was no probability that they would be obeyed. Foremost among the documents comes a writ referring to land on the border of Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, which shows us King William, like King Edward before him, sending his orders to the native authorities of the shire—in the present case the bishops of Ramsbury and Worcester, and two thegns named Eadric and Brihtric, with whom, however, Count Eustace of Boulogne is significantly associated.[179] From the other side of the country comes a more famous document in which William, “at the request of Abbot Brand,” grants to the said abbot and his monks of Peterborough the free and full possession of a number of lands in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. Leofric, abbot of Peterborough, had been mortally wounded at the battle of Hastings, and on his death the monks had chosen their provost Brand as his successor. He, not discerning the signs of the times, had gone and received confirmation from Edgar the Etheling, of whose inchoate reign this is the only recorded event; and it required the mediation of “many good men” and the payment 229of ten marks of gold to appease the wrath of William at such an insult to his claim. The present charter is the sign of William’s forgiveness, but for us its special interest lies in the fact that it shows us the king’s word already current by the Trent and Humber, while the appearance among its witnesses of “Marleswegen the sheriff” shows that the man to whom Harold had entrusted the command of the north did not see fit to continue resistance to the new king of England.[180]

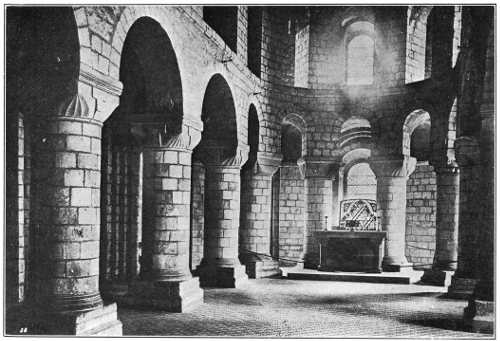

ST. JOHN’S CHAPEL, IN THE TOWER OF LONDON

Much more evidence, if we can trust it, pointing in the same direction, can be derived from a number of writs in English, which were apparently granted at this time in favour of Westminster Abbey.[181] Nothing could be more natural than that William at this time should show especial favour to the great religious house within whose precincts he had so recently been crowned, and although the language of these documents is very corrupt, and the monks of Westminster Abbey were practised and successful manufacturers of forged charters, there is not sufficient reason for us to condemn the present writs as spurious. And if genuine, and correctly dated, they add to the proof that William’s rule was 230accepted in many shires which had never yet seen a Norman army. The king greets Leofwine, bishop of Lichfield and Earl Edwin and all the thegns of Staffordshire in one writ; Ealdred, archbishop, and Wulfstan, bishop, and Earl William and all the thegns of Gloucestershire and Worcestershire in another; and if his rule was accepted in these three western shires, and also in the eastern counties represented by the Peterborough document, the submission of the midlands and in fact of the whole earldom of Mercia would seem to follow as a matter of course. It is also worth noting that no document relating to Northumbria, the one part of the country which offered a really protracted resistance to the Norman Conquest, can be referred to this early period in William’s reign.

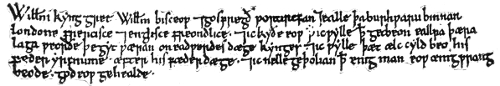

CHARTER OF WILLIAM I. TO THE LONDONERS

(IN THE ARCHIVES OF THE CORPORATION)

All this, therefore, should warn us against underrating the immediate political importance of the battle of Hastings. It did much more than merely put William into possession of the lands under the immediate rule of the house of Godwine; the overthrow of the national cause which it implied brought about so general a submission to the Conqueror that, with the possible exception of the Northumbrian risings, all subsequent resistance to him may with sufficient accuracy be described as rebellion. William, it would seem, at the time of his coronation, was the accepted king of all England south of the Humber, and the evidence which suggests this conclusion suggests 231also that at the outset of his reign he wished to interfere as little as possible with the native system of administration. Even in the counties which had felt his devastating march, English sheriffs continued to be responsible for the government of their wasted shires. Edmund, the sheriff of Hertfordshire, and “Sawold,” the sheriff of Oxfordshire, may be found in other writs of the Westminster series on which we have just commented. The Norman Conquest was to be followed by an almost complete change in the personnel of the English administration, but that change was first felt in the higher departments of government; the sheriffs of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire were not displaced, but Earl William Fitz Osbern, Count Eustace of Boulogne, and Bishop Odo of Bayeux begin to be held responsible for the execution of the king’s will in the shires where they had influence.

To the close of 1066 or the beginning of 1067 must also be assigned a charter of exceptional form and some especial constitutional interest in which King William grants Hayling Island, between Portsmouth and Chichester, to the monastery of Jumièges. In this document William is made to describe himself as lord of Normandy and “basileus” of England by hereditary right, and to say that, “having undertaken the government of England, he has conquered all his enemies.” One of these enemies, namely Earl Waltheof, attests the charter in question, and is flanked in 232the list of witnesses by Bishop Wulfwig of Dorchester, who died in 1067, and by one Ingelric, a Lotharingian priest who is known to have enjoyed William’s favour in the earliest years of his reign.[182] But it is the phrase “hereditario jure” which deserves particular attention. Rarely used in formal documents in later years, when the chancery formulas had become stereotyped, the words have, nevertheless, a prospective as well as a reflexive significance. They contain not only an enunciation of the claims in virtue of which King William had “undertaken the government of England,” but also a statement of the title by which that government would be handed down to his descendants. For, whatever may have been the title to the crown in the old English state, from the Norman Conquest onwards it has clearly become “hereditary” in the only sense in which any constitutional meaning can be attached to the word. Not a little of the evidence which has been adduced in favour of an “elective” tenure of the crown in Anglo-Norman and Angevin times is really the creation of an arbitrary construction of the terms employed. “Hereditary right” is not a synonym for primogeniture; the former words imply no more than that in any case of succession the determining factors would be the kinship of the proposed heir to the late ruler and the known intentions of the latter with 233respect to his inheritance. Disputed successions there were in plenty in the hundred and fifty years which followed the Conquest, but the essence of the dispute in each case was the question which of two claimants could put forward the best title which did not run counter to hereditary principles. The strictest law of inheritance is liable to be affected by extraneous complications when the crown is the stake at issue, and the disqualification which in 1100 attached to Robert of Normandy as an incapable absentee, in 1135 to Matilda the empress as a woman and the wife of an unpopular foreigner, in 1199 to Arthur as an alien and a minor, should not be allowed to mask the fact that in none of these cases did the success of a rival claimant contravene the validity of hereditary ideas. It was inevitable that, where the very rules of inheritance themselves were vague and fluctuating, the application made of them in any given instance should be guided by expediency rather than by a rigid adherence to the strict forms of law; yet nevertheless we may be sure that William Rufus and Henry I., like William the Conqueror, would claim to hold the throne of England not otherwise than “hereditario jure.”

At Barking the submission of the leading Englishmen went on apace. Besides Edwin and Morcar, Copsige, a Northumbrian thegn, and three other Englishmen called Thurkill, Siward, and Ealdred, were considered by Norman writers 234men of sufficient importance to deserve mention by name, and in addition to these shadowy figures we are told that many other “nobles” also came in at this time.[183] No apparent notice was taken by William of the tardiness of their submissions; all were received to favour, and among them must very probably be included the victim of the one great tragedy which stands out above all the disaster of the Conquest, Waltheof, the son of Siward. Waltheof was confirmed in his midland earldom of Northampton, and received a special mark of grace in being allowed to marry the Conqueror’s niece Judith, daughter of Enguerrand, the count of Ponthieu who had perished in the ambuscade at St. Aubin in 1054, by Adeliz, the daughter of Robert of Normandy and Arlette. Nor was this an isolated measure of conciliation, for one of William’s own daughters was promised to Earl Edwin, and in general it would seem that at this time any Englishman might look for favour if he liked to do homage and propitiate the new king with a money gift. The latter was essential, and from an incidental notice in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and a chance expression in the Domesday of Essex, it has been inferred that a formal “redemption” of their lands on the part of the English took place at this time.[184] The direct evidence for so far-reaching an event is 235certainly slight, but it would fall in well with the general theory of the Conquest if all Englishmen by the mere fact of their nationality were held to have forfeited their lands. William, it must always be remembered, claimed the throne of England by hereditary right. He had been defrauded of his inheritance by the usurpation of Harold, in whose reign, falsely so called according to the Norman theory, all Englishmen had acquiesced, and might therefore justly incur that confiscation which was the penalty, familiar alike to both races, for treason. Stern and even grotesque as this theory may seem to us, it was something more than a legal fiction, and we should be driven to assume for ourselves some idea of the kind even if we did not possess these casual expressions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Domesday scribe. On the one hand, all Englishmen had rejected William’s claim, and so many as could be hurried down to Hastings in time had resisted him in the open field; on the other hand, the number of Englishmen who were still holding land of the king twenty years after the Conquest was infinitesimal in comparison with the number who had suffered displacement. It would be natural to connect these two facts, but nothing is more probable in itself than that, before repeated rebellions on the part of the English had sharpened 236the edge of the Norman theory, the conquered race was given an opportunity of compounding for its original sin by making a deprecatory payment to the new lord of the land.

Nevertheless, it is to this period that we must undoubtedly assign the initial stages of the process which, before twenty years were over, was to substitute an alien baronage for the native thegnhood of England. It was clearly necessary that William should give some earnest at least of the spoils of war to his leading followers, and the amount of land already at his disposal must have been very considerable. The entire possessions of the house of Godwine were in his hands, and the one form of statecraft which that family had pursued with consistency and success had been the acquisition of landed property, nor do the dubious methods by which much of that property had been originally acquired seem to have invalidated King William’s tenure of it. The battle of Hastings, moreover, had been very fatal to the land-owning class of the southern shires, and no exception could be taken to William’s right to dispose of the lands of men who had actually fallen whilst in arms against him. Even in this simple way, the king had become possessed of no small territory out of which he could reward his followers, and the complicated nature of the Anglo-Saxon land-law assisted him still further in this respect. If, for instance, a thegn of Surrey had “commended” himself and his land to Harold as earl of 237Wessex, King William would naturally inherit all the rights and profits which were involved in the act of commendation: he could make a grant of them to a Norman baron, and thus, without direct injury being done to any man, the Norman would become possessed of an interest in the land in question, which, under the influence of the feudal ideas which accompanied the Conquest, would rapidly harden into direct ownership. In fact, there exists a considerable quantity of evidence which would suggest that a portion at least of the old English land-owning class was not displaced so much as submerged; that the Norman nobility was superimposed upon it as it were, and that the processes of thought which underlay feudal law invested the newcomers with rights and duties which made them in the eyes of the state the only recognised owners of the lands they held. We possess no detailed account of the great “confiscation” earlier than the Domesday Survey of twenty years after the battle of Hastings, and apart from the changes which must have occurred in the course of nature in that time, the great survey is not the sort of authority to which we should look for an accurate register of the fluctuating and inconsistent principles of a law of ownership which was derived from, and had to be applied to, conditions which were unique in Western Europe. But a priori it is not probable that all the thousands of cases in which an English land-owner has disappeared, and is represented 238by a Norman successor, should be explained by exactly the same principle in every instance. In one case the vanished thegn may have set out with Harold to the place of battle, and his holding have been given outright by the new king to some clamorous follower; in another, a dependent of the English earl of Mercia may have become peaceably enough a dependent of the Norman earl of Shrewsbury, and have sunk into the undifferentiated peasant class before the time arrived for Domesday to take cognisance of him; a third Englishman may have made his way to the court at Barking and bought his land of the Conqueror for his own life only, leaving his sons to seek their fortunes in Scotland or at Constantinople. The practical completeness of the actual transfer from the one race to the other should not lead us to exaggerate the simplicity of the measures by which it was brought about.[185]

One word should perhaps be said here about the character of the Anglo-Saxon thegnhood, on which the Conqueror’s hand fell so heavily. It was far from being a homogeneous class. At one end of the scale were great men like Esegar the Staller or Tochi the son of Outi, whose wide estates formed the bulk of the important Domesday fiefs of Geoffrey de Mandeville and Geoffrey Alselin. 239But, on the other hand, a very large proportion of the total number of men styled “thegns” can have been scarcely superior to the great mass of the peasantry whom the Norman lawyers styled collectively “villeins.” When we find in a Nottinghamshire village five thegns, each in his “hall,” owning between them land worth only ten shillings a year,[186] we see that we must beware of the romantic associations aroused by the word “thegn.” These men can have been distinguished from the peasantry around them by little except a higher personal status expressed in a proportionately higher wergild, and their depression into the peasant class would be rendered fatally easy by the fact that the law of status was the first part of the Anglo-Saxon social system to become antiquated. When the old rules about wer and wite had been replaced by the new criminal jurisprudence elaborated by the Norman conquerors, the one claim of these mean thegns to superior social consideration vanished. And lastly, it should be noted that where the Domesday Survey does reveal members of the thegnly class continuing to hold land directly of the king in 1086, it shows us at the same time that the class is very far from being regarded as on an equality with the Norman baronage. The king’s thegns are placed after the tenants in chief by military service, even after the king’s servants or “sergeants” of Norman birth; they are only entered as it were on 240sufferance, under a heading to themselves, at the very end of the descriptions of the several shires in which they are to be found.[187] They belonged in fact to an order of society older than the Norman military feudalism which supplanted them, and by the date of the Domesday Survey they were rapidly becoming extinct as a class in the shires south of the Humber, but no financial record like Domesday Book could be expected to tell us what became of them. Mere violent dispossession would no doubt be a great part of the story if told, but much of the change would have to be set down to the silent processes of economic and social reorganisation.

There remains one other legal document, more famous than any of these which we have considered, which was most probably granted at or about this time. The city of London had to be rewarded for its genuine, if belated, submission, and the form of reward which would be likely to prove most acceptable to the citizens would be a written security that their ancient customs and existing property should be respected by the new sovereign. And so “William the king greets William the bishop and Geoffrey the port-reeve and all the burghers, French and English, within London,” and tells them that they are to enjoy all the customs which they possessed in King Edward’s time, that each man’s property shall descend to his children, and that the king himself 241will not suffer any man to do them wrong.[188] Yet, satisfactory as this document may have been as a pledge of reconciliation between the king and his capital, it nevertheless bears witness in its formula of address to a significant change. Geoffrey the port-reeve is a Norman; he is very probably the same man as Geoffrey de Mandeville, the grandfather of the turbulent earl of Essex of Stephen’s day,[189] and his appearance thus early in the place of Esegar the Staffer suggests that the latter had gained little by his duplicity in the recent negotiations. It was of the first importance for William to be able to feel that London at least was in safe hands; he could not well entrust his capital and its new fortress to a man who had so recently held the city against him.

William’s rule in England was by this time so far accepted that he could afford to recross the Channel and show himself to his old subjects invested with his new dignities. The regency of Matilda and her advisers had, as far as we know, passed in perfect order, but it was only fitting that William should take the earliest opportunity of proving to the men of the duchy the perfect success of the enterprise, the burden of which they had borne with such notable alacrity. It was partly no doubt as an ostensible mark of confidence in English loyalty that, before crossing the Channel, William dismissed so many of his 242mercenary troops as wished to return home[190]; but their dismissal coincides in point of time with a general foundation of castles at important strategic points all over the south of England. The Norman castle was even more repugnant than the Norman man-at-arms to the Anglo-Saxon mind, and when the native chronicler gives us his estimate of William’s character and reign he breaks out into a poetic declamation as he describes the castles which the king ordered to be built and the oppression thereby caused to poor men.[191] But deeper than any memory of individual wrong must have rankled the thought that it was these new castles which had really rendered hopeless for ever the national cause of England; that local discontent might seethe and murmur in every shire without causing the smallest alarm to the alien lords ensconced in their stockaded mounds. The Shropshire-born Orderic, writing in his Norman monastery, gives us the true military reason for the final overthrow of his native country when he tells us that the English possessed very few of those fortifications which the Normans called castles, and that for this reason, however brave and warlike they might be, they could not keep up a determined resistance to their enemies. William himself had learned in Normandy how slow and difficult a task it was to reduce a district 243guarded by even the elementary fortifications of the eleventh century; he might be confident that the task would be impossible for scattered bodies of rustic Englishmen, in revolt and without trained leadership.

But for the present there seems to have been no thought of revolt; the castles were built with a view to future emergencies. No very elaborate arrangements were made for the government of England in William’s absence. It was entrusted jointly to William Fitz Osbern, the duke’s oldest friend, and Odo of Bayeux, his half-brother, who were to be assisted by such distinguished leaders of the army of invasion as Hugh de Grentmaisnil, Hugh de Montfort, and William de Warenne. The bishop of Bayeux was made primarily responsible for the custody of Kent, with its all-important ports, and the formidable castle of Dover. Hugh de Grentmaisnil appears in command of Hampshire with his headquarters at Winchester; his brother-in-law, Humphrey de Tilleul, had received the charge of Hastings castle when it was built and continued to hold it still; William Fitz Osbern, who had previously been created earl of Hereford, seems to have been entrusted with the government of all England between the Thames and the earldom of Bernicia, with a possible priority over his colleagues.[192] On his part, William 244took care to remove from the country as many as possible of the men round whom a national opposition might gather itself. Edgar the Etheling, earls Edwin, Morcar, and Waltheof, with Archbishop Stigand, and a prominent Kentish thegn called Ethelnoth, were requested to accompany their new king on his progress through his continental dominions.[193] We cannot but suspect that William must have felt the humour as well as the policy of attaching to his train three men each of whom had hoped to be king of the English himself; but it would have been impossible for the native leaders to refuse to grace the protracted triumphs of their conqueror, and early in the year the company set sail, with dramatic fitness, from Pevensey.

In the accounts which we possess of this visit, it appears as little more than a series of ecclesiastical pageants. William was wisely prodigal of the 245spoils of England to the churches of his duchy. The abbey church of Jumièges, whose building had been the work of Robert, the Confessor’s favourite, was visited and dedicated on the 1st of July, but before this the king had kept a magnificent Easter feast at Fécamp[194] where, thirty-two years before, Duke Robert of Normandy had prevailed upon the Norman baronage to acknowledge his seven-year-old illegitimate son as his destined successor. The festival at Fécamp was attended by a number of nobles from beyond the Norman border, who seem to have regarded Edwin and Morcar and their fellows as interesting barbarians, whose long hair gave unwonted picturesqueness to a formal ceremony. At St.-Pierre-sur-Dive, where William had spent four weary weeks in the previous autumn, waiting for a south wind, another great assembly was held on the 1st of May, to witness the consecration of the new church of Notre Dame. Two months later came the hallowing of Jumièges; and the death of Archbishop Maurilius of Rouen, early in August, seems to have given occasion for another of these great councils to meet and confirm the canonical election of his successor. The monks of Rouen cathedral had chosen no less a person than Lanfranc of Caen as their head, but he, possibly not without a previous consultation with his friend and lord King William, declined the office, and when on a 246second election John, bishop of Avranches, was chosen, Lanfranc went to Rome and obtained the pallium for him.[195] Whether Lanfranc’s journey possessed any significance in view of impending changes in the English Church, is unfortunately uncertain for lack of evidence; but his refusal of the metropolitan see of Normandy suggests that already he was privately reserved for greater things. In any case, he is the man to whom we should naturally expect William to entrust such messages as he might think prudent to send to the Pope concerning his recent achievements and future policy in England.

From his triumphal progress in Normandy, William was recalled by bad news from beyond the Channel. Neither of his lieutenants seems to have possessed a trace of the more statesmanlike qualities of his chief. William Fitz Osbern, good soldier and faithful friend to William as we may acknowledge him to have been, did not in the least degree understand the difficult task of reconciling a conquered people to a change of masters, and Bishop Odo has left a sinister memory on English soil. William’s departure for Normandy was signalised by a general outbreak of the characteristic vices of an army of occupation, in regard to which the regents themselves, according to the Norman account, were not a little to blame. Under the stimulus of direct oppression, and in the temporary absence of the dreaded 247Conqueror, the passive discontent of the English broke out into open revolt in three widely separated parts of the kingdom.

Of the three risings, that in the north was perhaps the least immediately formidable, but the most suggestive of future difficulties for the Norman rulers. Copsige, the Northumbrian thegn who had submitted at Barking, had been invested with the government of his native province, but the men of that district continued to acknowledge an English ruler in Oswulf, the son of Eadwulf, who had been subordinate earl of Bernicia under Morcar. Copsige in the first instance was able to dispossess his rival, but the latter bided his time, collected around him a gang of outlaws, and surprised Copsige as he was feasting one day at Newburn-on-Tyne. The earl escaped for a moment, and took sanctuary in the village church; but his refuge was betrayed, the church was immediately set on fire, and he himself was cut down as he tried to break away from the burning building.[196] The whole affair was not so much a deliberate revolt against the Norman rule as the settlement of a private feud after the customary Northumbrian fashion, and it may quite possibly have taken place before William had sailed for Normandy. Oswulf was able to maintain himself through the following summer, but then met his end in an obscure 248struggle with a highway robber, and the province was left without an earl until the end of the year, when Gospatric, the son of Maldred, a noble who possessed an hereditary claim to the title, came to court and bought the earldom outright from William.[197] In the meantime, however, the Northumbrians were well content with a spell of uncontested anarchy, and they made no attempt to assist the insurgents elsewhere in the country.

The leader of the western rising was a certain Edric, nicknamed the “Wild,” whom the Normans believed to be the nephew of Edric Streona, the famous traitor of Ethelred’s time. This man had submitted to the Conqueror, but apparently refused to accompany him into Normandy, and the Norman garrison of Hereford castle began to ravage his lands. In this way he was driven into open revolt, and he thereupon invited Bleddyn and Rhiwallon, the kings of Gwynedd and Powys, to join him in a plundering expedition over Herefordshire, which devastated that country as far as the river Lugg, but cannot have done much to weaken the Norman military possession of the shire.[198] Having secured much booty, Edric withdrew into the hills with his Welsh allies, and next appears in history two years later, when he returned to play a part in the general tumult which disquieted England in 1069.

The most formidable of the three revolts which 249marked the period of William’s absence had for its object the recovery of Dover castle from its Norman garrison.[199] It is the one rising of the three which has an intelligible military motive, and it contains certain features which suggest that it was planned by some one possessed of greater political ability than can be credited to the ordinary English thegn. Count Eustace of Boulogne, the man of highest rank among the French auxiliaries of the Conqueror, had already received an extensive grant of land in England as the reward for his services in the campaign of Hastings, but he had somehow fallen into disfavour with the king and had left the country. The rebel leaders knowing this, and judging the count to be a competent leader, chose for once to forget racial differences in a possible chance of emancipation, and invited him to cross the Channel and take possession of Dover castle. Eustace, like Stephen of Blois, a more famous count of Boulogne, found it an advantage to control the shortest passage from France to England; he embarked a large force of knights on board a number of vessels which were at his command, and made a night crossing in the hope of finding the garrison within the castle off their guard. At the moment of his landing Odo of Bayeux and Hugh de Montfort happened to have drawn off the main body of their troops across the Thames; a fact which suggests that the rebels had observed unusual secrecy 250in planning their movements. The count was therefore able to occupy the town, and to lay siege to the castle without hindrance, but failed to take the garrison by surprise, as he had hoped, and met a spirited resistance. The assault lasted for some hours, but the garrison more than held their own, and at last Eustace gave his troops the signal to retire to their ships, although it was known that a delay of two days would have brought large reinforcements to the side of the insurgents. It must also have been known that the same time would have brought Odo of Bayeux with his trained troops within dangerous proximity to Dover; and the impossibility in the eleventh century of successfully conducting a siege against time is some excuse for Eustace’s rather ignominious withdrawal. The first sign of retreat, however, was turned to the advantage of the garrison, who immediately made a sally and threw the besiegers into a state of confusion which was heightened by a false rumour that the bishop of Bayeux was at hand. A large part of the Boulogne force was destroyed in a desperate attempt to reach the ships, a number of men apparently trying to climb down the face of the cliffs on which Dover castle stands. Count Eustace himself, who knew the neighbourhood, became separated from his men and escaped on horseback to an unrecorded port, where he was fortunate enough to find a ship ready to put out to sea. The English, thus deprived of their leader, dispersed 251themselves over the country, and so avoided the immediate consequences of their rout, since the Norman force in Dover was not strong enough to hunt down the broken rebels along all their scattered lines of retreat.[200]

With his kingdom outwardly restored to order, but simmering with suppressed revolt, William set sail from Dieppe on the 6th of December, and landed at Winchelsea on the following day. Queen Matilda was still left in charge of Normandy, but her eldest son, Robert, was now associated with her in the government, and Roger de Beaumont, who had been the leading member of her council during her regency in 1066, on this occasion accompanied his lord to England.[201] The king kept his Christmas feast at Westminster; a ceremony in which the men of both races joined on an equal footing, and for the moment there may have seemed a possibility that the recent disorders had really been the last expiring efforts of English nationalism. Yet the prospect for the new year was in reality very threatening. The political situation in England at this time is well described by Ordericus Vitalis, who tells us that every district of which William had taken military possession lay at his command, but that in the extreme north and west men were only 252prepared to render such obedience as pleased themselves, wishing to be as independent of King William as they had formerly been independent of King Edward and his predecessors.[202] This attitude, which supplies a partial explanation of the overthrow of England in 1066, and a partial justification of the harrying of Northumbria in 1069, supplies also a clue to the purpose underlying William’s ceaseless activity during the next two years. At Exeter, Stafford, and York, William was, in effect, teaching his new subjects that he would be content with nothing less than the unqualified submission of the whole land; that England was no longer to be a collection of semi-independent earldoms, but a coherent state, under the direct rule of a king identified with Wessex no more than with Northumbria or East Anglia. The union of England, thus brought at last into being, was no doubt achieved almost unconsciously under the dictation of the practical expediency of the moment, but this does not detract from the greatness of the work itself, nor from the strength and wisdom of the Conqueror whose memorial it is.

Meanwhile, danger from a distant quarter was threatening the Norman possession of England. Events which were matters of very recent history had proved that English politics were still an object of interest to the rulers of Norway and Denmark; and the present was an opportunity which could not fail to attract any Scandinavian 253prince who would emulate the glory of the great kings of the last generation. The death of Harold Hardrada, which had thrown the Norwegian claims on England into abeyance for a time, had left Swegn Estrithson, king of Denmark, unquestionably the most considerable personage in the Scandinavian world; and to him accordingly the English leaders, or such at least of them as were at liberty, had appealed for help during the preceding months.[203] As a Dane himself and the nephew of Cnut, Swegn Estrithson could command the particular sympathy of the men of Northumbria and would not be unacceptable to the men of the southern Danelaw; no native claimant possessed similar advantages in respect to anything like so large a part of England. Swegn indeed, whose prevailing quality was a caution which contrasts strangely with the character of his Danish ancestors and of his great Norwegian rival, had delayed taking action up to the present, but it was the fear that a northern fleet might suddenly appear in the Humber which had really been the immediate cause of William’s return from Normandy.

At this moment, with the imminent probability of invasion hanging over the north and east of his kingdom, William was called away from his head-quarters at London by the necessity of suppressing a dangerous rising in the extreme west. It is 254probable that William’s rule had not yet been commonly recognised beyond the eastern border of Devonshire, although on the evidence of writs we know that Somerset was already showing him ostensible obedience. But the main interest of the following episode lies in the strangely independent attitude adopted by the city of Exeter. In the eleventh century the capital of Devon could undoubtedly claim to rank with York, Norwich, and Winchester among the half-dozen most powerful cities in England. With its strong fortifications which made it in a sense the key of the Damnonian peninsula, commanding also important trade routes between England, Ireland, and Brittany, Exeter in English hands would be a standing menace to the Norman rule scarcely less formidable than an independent York. The temper of the citizens was violently anti-Norman, and they proceeded to take energetic measures towards making good their defence, going so far as to impress into their service such foreign merchants within the city as were able to bear arms. We are also told that they tried to induce other cities to join them in resisting the foreign king, and it is not impossible that they may have drawn reinforcements from the opposite shore of Brittany. It was of the first importance for William to crush a revolt of this magnitude before it had time to spread, but before taking action, and probably in order to test the truth of the reports which had come to 255him as to what was going on in Devonshire, he sent to demand that the chief men of Exeter should take the oath of allegiance to him. They in reply proposed a curious compromise, saying that they were willing to pay the customary dues of their city to the king, but that they would not swear allegiance to him nor admit him within their walls. This was almost equivalent to defiance and elicited from William the remark that it was not his custom to have subjects on such terms. Negotiations in fact ceased; Devonshire became a hostile country, and William marched from London, making the experiment, doubly bold at such a crisis, of calling out the native fyrd to assist in the reduction of their countrymen.

The men of Exeter, on hearing the news of William’s approach, began to fear that they had gone too far; and, as the king drew near, the chief men of the city came out to meet him, bringing hostages and making a complete capitulation. William halted four miles from the city, but the envoys on their return found that their fellow-citizens, unwilling apparently to trust to the king’s mercy, were making preparations for a continued resistance, and they threw in their lot with their townsmen. William was filled with fury on hearing the news. His position was indeed sufficiently difficult. It was the depth of winter; part of his army was composed of Englishmen whose loyalty might not survive an unexpected check to his arms, and Swegn of Denmark might land in the 256east at any moment. Before investing the city William tried a piece of intimidation, and when the army had moved up to the walls, one of the hostages was deliberately blinded in front of the gate. But it would seem that the determination of the citizens was only strengthened by the ghastly sight, and for eighteen days William was detained before the gates of Exeter, despite his constant endeavours either to carry the walls by assault or to undermine them.

At last, after many of his men had fallen in the attack, it would seem that the Conqueror for once in his life was driven to offer terms to the defenders of a revolted city. The details of the closing scene of the siege are not very clear; but it is probable that the more important citizens were now, as earlier in the struggle, in favour of submission, and that they persuaded their fellows to take advantage of King William’s offer of peace. They had indeed a particular reason for trying to secure the royal favour, for the chief burden of taxation in any town fell naturally upon its wealthier inhabitants, and on the present occasion William seems to have given a promise that the customary payments due to the king from the town should not be increased. The poorer folk of Exeter secured a free pardon and a pledge of security for life and property, but the conduct of their leaders undoubtedly implies a certain lack of disinterested zeal for the national cause; and the native chronicler significantly remarks 257that the citizens gave up the town “because the thegns had betrayed them.” The other side of the picture is shown by Ordericus Vitalis, who describes how “a procession of the most beautiful maidens, the elders of the city, and the clergy carrying their sacred books and holy vessels” went out to meet the king, and made submission to him. It has been conjectured with great probability that the real object of the procession was to obtain from the king an oath to observe the terms of the capitulation sworn on the said “sacred books and holy vessels,” and in any case the witness of Domesday Book shows that Exeter suffered no fiscal penalty for its daring resistance. To keep the men of Exeter in hand for the future a castle was built and entrusted to Baldwin de Meules, the son of Count Gilbert of Brionne, but this was no mark of particular disfavour, for it was universally a matter of policy for William to guard against civic revolts by the foundation of precautionary fortresses.[204]

One immediate consequence of the fall of Exeter was the flight and final exile of one of the two greatest ladies in England at this time. Gytha, the niece of Cnut, and the widow of Earl Godwine, through whom Harold had inherited a strain of royal blood, had taken refuge in Exeter, and now, before William had entered the city, made her escape by water with a number of other 258women, who probably feared the outrages which were likely to occur upon the entry of the northern army. They must have rounded the Land’s End, and sailed up the Bristol Channel, for they next appear as taking up their quarters on a dismal island known as the Flat Holme, off the coast of Glamorgan. Here they stayed for a long while, but at last in despair the fugitives left their cheerless refuge and sailed without molestation to Flanders, where they landed, and were hospitably entertained at St. Omer. Nothing more is recorded of the countess; but her daughter Gunhild entered the monastic life and died in peace in Flanders in 1087, some two months before the great enemy of her house expired at Rouen.

It is likely enough that Gytha chose the Flat Holme as her place of refuge with the hope of joining in a movement which at this time was gathering head among the English exiles in Ireland. It is at least certain that, before the summer was over, three of Harold’s illegitimate sons, who had spent the previous year with the king of Dublin, suddenly entered the Devon seas with fifty-four ships. They harassed the south coast of the Bristol Channel, and even made bold to enter the Avon and attack Bristol itself, but were driven off without much difficulty by the citizens of the wealthy port, and sailing back disembarked at some unknown point on the coast of Somerset. Here they were caught and soundly beaten by the Somersetshire natives under the 259leadership of Ednoth, an Englishman who had been master of the horse to Edward the Confessor, but who was clearly ready to do loyal service to the new king. Ednoth was killed in the battle, but the raiders were compelled to take to their ships, and after a brief spell of desultory ravage along the coast they sailed back to Ireland, having done nothing to weaken the Norman grip upon the south-west of England, but gaining sufficient plunder to induce them to repeat their expedition in the course of the following year.[205]

It was well for William that even at the cost of some loss of prestige he had gained possession of Exeter in the first months of 1068, for the remainder of the year saw a general outburst of revolt against the Norman rule. Before returning to the east of England, William made an armed demonstration in Cornwall; and it was very possibly at this time that he established his half-brother, Count Robert of Mortain, in a territorial position in that Celtic land which shows that the Conqueror was quite willing upon occasions to create compact fiefs according to the continental model. Count Robert was never invested with any formal earldom of Cornwall, but in the western peninsula he occupied a position of greater territorial strength, if of lower official rank, than that held by his brother, Bishop Odo, in his distant shire of Kent. The revolt of Exeter had no 260doubt taught William that it would be advisable to take any future rising in Devonshire in the rear by turning Cornwall into a single Norman estate, and his own presence with an army in the west at this time would go far to simplify the preliminary work of confiscation.

His Cornish progress over, King William marched eastwards, disbanded the fyrd, and kept his Easter feast (March 23d) at Winchester. For a few weeks the land was at peace, and during this breathing space the Duchess Matilda came across into England, and was crowned at Westminster on Whitsunday (May 11th), by Ealdred, archbishop of York. The event was a clear expression of William’s desire to reign as an English king, for Matilda stayed in England, and her fourth son, Henry, who was born early in the next year, possessed in English eyes the precedence, which by Anglo-Saxon custom belonged to the son of a crowned king and his lady, born in the land. Robert, the destined heir of Normandy, seems to have remained in charge of the duchy, and Richard, the Conqueror’s second son, probably accompanied his mother across the Channel. By a fortunate chance, we happen to know with exactitude the names of those who were present at the Whitsuntide festival,[206] and the list is significant. Among the members of the clerical estate 261the Norman hierarchy supplied the bishops of Bayeux, Lisieux, and Coutances, but the arch-bishops of Canterbury and York and the bishops of Exeter, Ramsbury, Wells, and London were all of English appointment, although the last four of them were of foreign birth, and the eight abbots who were present were also men of King Edward’s day. The laymen who attended the ceremony formed a more heterogeneous group; Edwin, Morcar, and Waltheof seem strangely out of place side by side with the counts of Mortain and Eu; with William Fitz Osbern, Roger de Montgomery and Richard, the son of Count Gilbert of Brionne. The company which came together in Westminster Abbey on that Whitsunday supplies a striking picture of the old order which was changing but had not yet given place to the new, and it is a notable thing that the ancestress of all Plantagenet, Tudor, and Stuart kings should have been crowned in the sight of men who had held the highest place in the realm in the last days of independent England.

This solemn inauguration of the new dynasty can have been passed but a few weeks before William had to resume the dreary task of suppressing his irreconcilable subjects. After a year and a half of acquiescence in the Norman rule, Earls Edwin and Morcar suddenly made a spasmodic attempt to raise the country against the foreigners. Their position at William’s court must have been ignominious at the best, and 262although, as we have seen, the king had promised one of his daughters in marriage to Edwin, he had withheld her up to the present in deference to the jealousy which his Normans felt for the favoured Englishman. Under the smart of their personal grievances, Edwin and his brother broke away from the court, and headed a revolt which, although general in character, seems to have received most support in Morcar’s earldom of Northumbria. The rising is also marked by a revival of the alliance between the house of Leofric and the Welsh princes which had been an occasional cause of disquiet during the Confessor’s reign; for Bleddyn, the king of North Wales, came to the assistance of Edwin and Morcar,[207] as in the previous year he had joined the Herefordshire raid of Edric the Wild. The rising was the occasion for a general secession of the leading Englishmen from William’s court, for Edgar the Etheling and his mother and sisters, together with Marleswegen and many prominent Northumbrians, headed by Gospatric, their newly appointed earl, probably fearing that they might be held implicated in the guilt of Edwin and Morcar, made a speedy departure for the north country.[208]

263The focus of disturbance was evidently the city of York. It is not probable that William had hitherto made any systematic attempt to establish Norman rule beyond the Humber, but we get a glimpse of the venerable Archbishop Aldred making strenuous efforts to restrain the violence of the men of his city. His protestations were useless, and while the Northumbrians were enthusiastically preparing for war after the manner of their ancestors, William was taking steps which brought the revolt to an end within a few weeks without the striking of a single blow.

It is in connection with these events that Orderic makes the observations which have already been quoted about the part played by the Norman castle in thwarting the bravest efforts of insurgent Englishmen. Some of the greatest fortresses of medieval England derive their origin from the defensive posts founded by William during the war of 1068. “In consequence of these commotions,” said Orderic, “the King carefully surveyed the most inaccessible points in the country, and, selecting suitable places, fortified them against the raids of the enemy.”[209] But besides these “inaccessible points” we have seen that William made it a matter of regular policy to plant a castle in all the greater boroughs and 264along all the more important lines of road in the country, and, the present campaign affords an excellent example of his practice in this matter. The first fortress recorded as having been built at this time was the humble earthwork which developed in the next two centuries into the magnificent castle of Warwick. Henry de Beaumont, son of the Roger de Beaumont who had been Queen Matilda’s adviser in 1066, was placed in command of it, and the Conqueror marched northward; but, possibly before he had left the Avon valley, Edwin and Morcar, now as ever unable to follow a consistent course of action, suddenly abandoned their own cause and made an ignominious submission. The surrender of the rebel leaders did not affect the king’s movements; he continued his advance, probably harrying the plain of Leicester as he passed across it, and at Nottingham, on a precipitous cliff overhanging the town, he placed another castle, commanding the Trent valley at the point where the river is crossed by one of the great roads from London to the north of England. The march was resumed without delay, and at some point on the road north of Nottingham the army was met by the citizens of York, bringing the keys of their city, and offering to give hostages for their future good behaviour. The defection of Edwin and Morcar had deprived the rising of its nominal leaders, and the military occupation of Nottingham had threatened to isolate the revolted area; but it is 265also probable that William’s rapid movements had surprised the defenders of the northern capital before their preparations were completed. At York itself a certain Archil, who was regarded by the Normans as the most powerful man in Northumbria, came in to William and gave his son as a hostage, and on the line of the city walls, at the junction of the rivers Ouse and Foss, there arose the third castle of this campaign, now represented only by the mound on which rests the famous medieval keep known as “Clifford’s Tower.” The fortress was garrisoned with picked men, but its castellan, Robert Fitz Richard, is only known to us through the circumstances of his death in the next year.

Other matters than the fortifications of York demanded King William’s attention at this time. Danger was threatening from the side of Scotland, for the rebels had sought the help of King Malcolm Canmore, and a great army was gathering beyond the Tweed. The northern frontier of England was as yet unprotected by the castles of Berwick and Carlisle, and on the west the possessions of the king of Scots extended as far south as Morecambe Bay. Also the best English authority asserts that Edgar the Etheling and his friends had already taken refuge with King Malcolm on their flight from William’s court, and the marriage of the etheling’s sister to the Scottish king was very shortly to make the northern kingdom a point d’appui for all unquiet nationalists in 266England. There was clearly good reason for William to define his position with regard to the king of Scots, and this the more as it would give him an opportunity of claiming fealty as well as submission at a moment when he was all-powerful in the north. An ambassador was found in the person of Bishop Ethelwine of Durham, who had revolted with the rest of Northumbria, but had made his peace with the Conqueror, and conducted the present business to a successful issue. King Malcolm sent representatives to York in company with the bishop of Durham, and according to the Norman account they swore fealty to William in the name of their master. It was no part of the Conqueror’s plan to engage in an unnecessary war in Scotland, and, all the purposes of his northern journey being for the present accomplished, he turned south again by way of Lincoln, Huntingdon, and Cambridge, at each of which places the inevitable castle was raised and garrisoned.[210]

Denier of Baldwin of Lille

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content