Search london history from Roman times to modern day

The year 1068 had closed under a specious appearance of peace, and the only result of the revolts of Exeter and York had been a proof of the futility of isolated resistance to a king who could strike with equal decision at the west or north. The following year opened with two north-country risings which formed an unconcerted prelude to fifteen months of incessant strife, in which the strength of the Norman hold on England was finally tested and proved. The flight of Gospatric in the previous summer had vacated the Bernician earldom, and at the beginning of 1069 the Conqueror tried the experiment of appointing a NormanNorman baron to the command of the border province. His choice fell on one Robert de Comines, who immediately set out for the north at the head of a force of five hundred knights. The news of his appointment preceded him, and the men of Northumbria, who had enjoyed virtual independence for two years, were not minded to submit quietly to the rule of a foreign earl. A league was accordingly formed, the members of which bound themselves either to kill the stranger or to perish in the attempt. 268Bishop Ethelwine of Durham had evidently heard rumours of the plot, for as the earl approached Durham he was met by the bishop, who warned him of the impending danger. Robert took no heed, and his troops behaved badly as they entered Durham, killing certain of the bishop’s humbler tenants, but meeting no armed opposition. The earl was entertained in a house belonging to the bishop, and his men were quartered all over the town, in open defiance of the bishop’s warning. But during the night a large body of Northumbrians moved up to the city, and as dawn broke they burst through the gates and began a deliberate massacre of the Frenchmen. The surprise was complete, but the earl and his immediate companions were aroused in time to enable them to make a fight for their lives. They could expect no quarter, and their defence was so desperate that the rebels were unable to break into the house, and at last set it on fire, the earl and his men perishing in the flames. Of the five hundred Normans in Durham, only one survivor made his escape.[211]

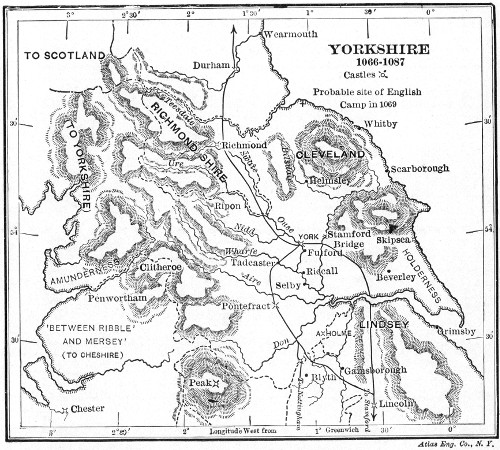

YORKSHIRE

1066–1087

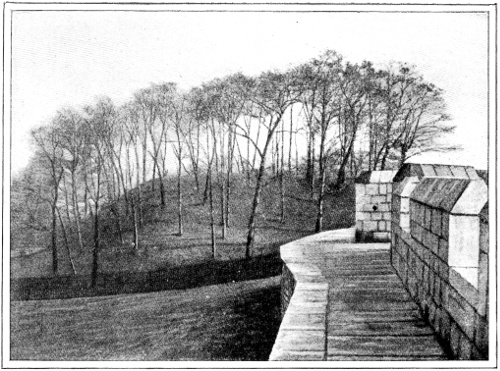

This episode was quickly followed by the death of Robert Fitz Richard, the governor of York, who perished with a number of his men in an obscure struggle, which nevertheless left the castle untaken in Norman hands. Encouraged by these events, Edgar the Etheling, Marleswegen, Archil, and Gospatric reappeared upon the scene, 269and made a determined attack upon the fortress, so that William Malet, who would appear to have become castellan on Robert Fitz Richard’s death, sent an urgent message to the king, saying that he must surrender at once unless he received reinforcements. Upon receiving this appeal, the Conqueror flew in person to York, scattered the rebels with heavy loss, and planted a second castle within a few hundred yards of the first, but on the opposite bank of the Ouse. This fortress, of which the mound, known as the Baile Hill, still rests against the city wall, was committed to the charge of no less a person than Earl William Fitz Osbern, and the king after eight days returned to Winchester to keep his Easter feast there. His departure was followed by a renewal of the English attack, now directed against both the castles, but William Fitz Osbern and his men gave a good account of themselves against the insurgents.[212]

It was, however, apparent by this time that a spirit of revolt was generally abroad, and Queen Matilda was sent back into Normandy to assume command of the duchy once more. No very coherent narrative of the military events of this year can be extracted from the confused tale of Ordericus Vitalis or the jejune annals of the 270Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but the outline of the history is fairly plain. We seem to recognise three distinct areas of revolt: Devon and Somerset, Shropshire and Staffordshire, and, most dangerous of all, Yorkshire and the north. We have no reason to suppose that the English leaders had any thought of uniting in common resistance to the Norman rule; their plans extended to nothing more than the destruction of single fortresses, the execution of isolated revenge for local injuries. On the other hand the dispersion of the centres of revolt incidentally produced some of the effects of combination; the Normans were compelled to divide their forces, and the rapidity with which King William dashed about the country from point to point proved that he at least thought the situation sufficiently precarious.

THE BAILE HILL, YORK

THE SITE OF WILLIAM I.’S SECOND CASTLE

Early in the summer the three sons of Harold repeated their piratical excursion of the previous year. They landed on the 24th of June in the mouth of the Taw with sixty-six ships and raided over a large part of Devonshire, but were beaten off at last by Brian of Penthievre, and vanish therewith from English history.[213] The local forces were capable of dealing with an unsupported raid of this kind, but the case was otherwise with the powerful armament which at this time was being prepared in the fiords of Denmark. Swegn Esthrithson at last was about to take action, and the news excited once more 271the unstable patriotism of the men of Northumbria. The Danish army was recruited from a wide area to the south of the Baltic; there were numerous adventurers from Poland, Frisia, and Saxony, and we read of a contingent of heathen savages from Lithuania. The fleet was reported to consist of two hundred and forty vessels; a number capable, if each ship was fully laden, of carrying a force considerably larger than any army William could put into the field without calling out the native militia. The expedition was under the command of Harold and Cnut, the sons of King Swegn, and Asbiorn, his brother, and included many Danes of high rank, among whom Christian, bishop of Aarhus, is mentioned by name.[214]

The fleet set sail towards the end of August, and must have hugged the shores of Frisia and Holland, for it first touched the English coast at Dover. The royal forces were strong enough to prevent a landing both here and at Sandwich, where the Danes repeated the attempt, but the mouth of the Orwell was unguarded, and a body of the invaders disembarked at Ipswich with the intention of plundering the neighbourhood. We are, however, told that the “country people,” 272by which phrase the English peasantry of the district are probably meant, came out and, after killing thirty of the raiders, drove the rest to seek refuge in their ships. A similar descent on Norwich was repulsed by Ralf de Wader, earl of East Anglia and governor of Norwich castle, and the Danes passed on towards the Humber. In the meantime, news of these events was brought to King William, who, we are told, was hunting at the time in the forest of Dean away on the Welsh border; and he, seeing where the key to the situation really lay, instantly sent a messenger to York to warn the garrison and to direct that they should summon him in person if they were hard pressed by the enemy. He received the reassuring answer that they would require no assistance from him for a year to come, and he accordingly continued to leave the defence of the north in the hands of his subordinates, while the Danes were sailing along the coast of Lindsey.

It is an interesting question how far the men of the English Danelaw may have been led by a remembrance of their Scandinavian origin to make common cause with the army of the king of Denmark at this time. At the beginning of the century Swegn Forkbeard had been welcomed on this account by the men of the shires along the lower Trent, and had fixed his headquarters at Gainsborough in this district. So long as the Anglo-Saxon legal system retained a semblance of vitality a very definite barrier of customary 273law separated the Danelaw from the counties of the eastern midlands, and the details of its local organisation still preserved not a few peculiar features, plainly referable to a northern origin. On the other hand, in the names of the pre-Conquest owners of land in this district as recorded in Domesday Book the English element distinctly preponderates, while the particularism of Northumbria itself was perhaps rather political than racial. It is probable that the men of Lincolnshire would have preferred a Danish to either a Norman or an English king, but they play no distinctive part in the incidents of this campaign, which centres round the city of York and its approaches by land and water.

While the Danish fleet still hung in the Humber, it was joined by the English exiles from Scotland, Edgar the Etheling, Gospatric, and Marleswegen, with whom Waltheof, the earl of Huntingdon, and others of lesser fame now associated themselves. Edgar, who had been raiding in Lincolnshire independently of his Danish friends, had narrowly escaped capture by the garrison of Lincoln castle; but he reached the Humber in safety though with only two companions, and the combined force, like that of Harold Hardrada three years before, passed on up the Ouse and disembarked for a direct attack on York. Volunteers assembled from all the neighbouring country, and in numbers at least it was a formidable army which on the 21st of September appeared before the northern 274capital, the English forming the van, the Danish host the rear. The Normans in York made no attempt to hold the city wall, and concentrated their defence on the two fortresses by the Ouse, setting fire to the adjoining buildings, so that their timber might not be used to fill up the castle ditches. The flames spread, the city was gutted, and, what was worse to the medieval mind, the church of St. Peter was involved in the ruin. The struggle which followed was soon over; on the very day of the Danish arrival, while the city was still burning, the garrison of the castles made a sally, were outnumbered by the enemy within the city walls and destroyed, after which the capture of the actual fortifications was an easy matter. The castles themselves were only wooden structures planted on mounds of earth; their defenders had been hopelessly weakened by the failure of the sally, and later tradition recounted in verse how Waltheof, Siward’s son, stood by the gate and smote down the Normans one by one to the number of a hundred with his axe as they tried to break away.[215] The castles once taken, the English hatred of these signs of bondage broke out with 275fury; the wooden buildings were instantly broken up and hurled to the ground, and the luckless William Malet, with his wife and children, a prisoner, was one of the few Normans in York who survived the day.

On the 11th of September, before the Danish army had sighted the walls of York, Archbishop Ealdred, one of the few Englishmen of high rank who accepted the Norman Conquest as irreversible, died, being worn out by extreme age, and grief at the ruin which he foresaw was about to fall on the men of his province. The fall of York was the most serious check which had hitherto crossed King William’s plans in Normandy or England; it might easily lead to the formation of a Danish principality beyond the Humber; it was certain to give encouragement to rebellious movements in the south. In his rage at the news the king caused the fugitives who had told the tale to be horribly mutilated as a warning to his captains against possible treachery[216] and then set out for the north. As he drew towards the Northumbrian border, the Danes abandoned their new conquest, and made for their ships, crossing the Humber in them, and established themselves among the marshes of the Isle of Axholme. This movement diverted the king’s march; he struck straight for Lindsey with a force of cavalry and crushed sundry isolated bodies of 276the enemy which were dispersed among the fens. The Danes, finding their position untenable, took to their ships again and crossed over to the Yorkshire bank, whither William had no means of following them. He therefore left part of his troops under the counts of Mortain and Eu, to protect Lindsey, while he himself turned westwards to suppress a local rising which had broken out at Stafford.

We know nothing as to the persons who were responsible for this last revolt, nor have we any clue as to their objects, but it is quite possible that they were acting in concert with the men who at this time were laying siege to the new castle of Shrewsbury. William in this year was contending with men of Celtic as well as of Scandinavian race; for Bleddyn, king of Gwynedd, for the third time within three years, had taken arms against the Normans on the Welsh border. To the men of North Wales, Edric the Wild brought a contingent from Herefordshire, and the citizens of Chester, which, it would seem, had not as yet been occupied by the Normans, joined in the attack. The allies were successful in burning the town of Shrewsbury and getting away before a Norman force arrived in relief of the castle, but the Staffordshire insurgents were less fortunate. We are merely told that King William “wiped out great numbers of the rebels with an easy victory at Stafford,” but the Domesday survey of the country, in the large proportion of land which it 277returns as “waste,” suggests that Staffordshire at this time received at William’s hand some measure of the doom which was to fall upon Yorkshire before the year had closed.

In the meantime the revolt of the south-west had run its course. Here as elsewhere the plans of the revolted English do not seem to have extended beyond the capture of individual castles; notably the royal fortress which had been built in Exeter after the the siege of the previous year, and the private stronghold of Count Robert of Mortain at Montacute in Somerset. The command against the besiegers of Montacute was assumed by Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances, who speedily scattered the insurgents with an army drawn from London, Winchester, and Salisbury, the chief towns on the main road from the east to Devon and Somerset. The situation at Exeter was complicated by the attitude of the citizens themselves, who must have been anxious not to forfeit the privileges which they had obtained from King William by the treaty which had so recently concluded their own revolt. Accordingly, when the new castle was beset by a host of Devonians and Cornishmen, the townspeople took the Norman side; and the garrison on making a sally threw the rebels into a state of confusion which was completed by the arrival of Brian of Penthievre, who was advancing to the relief of the castle men.

Now that no further danger was to be apprehended, from the lands between Trent and Severn 278King William’s hands were free to deal with the Northumbrian difficulty. His lieutenants in Lindsey had contrived to surprise a number of the Danes as they were participating in the village feasts with which the men of that district were anticipating the customary orgies of midwinter and to which they had apparently invited their Danish friends. This, however, was a trivial matter; there was a probability that the Danes would return to take possession of York, and when the Conqueror next appears after the battle of Stafford, he is found at Nottingham on his way to the northern capital. For fifty miles north of Nottingham he followed the route by which he had advanced on to York in the previous year, but he received a sudden check at the point where the road in question crosses the Aire near to the modern town of Pontefract. The bridge was broken, and the river, swollen most probably by the winter’s rains, could neither be forded nor crossed in boats, while the enemy lined the opposite bank in force. On this last account it was impossible to rebuild the bridge, and for three weeks the army was kept inactive by this unexpected obstacle. At last a knight called Lisois de Monasteriis, after examining the river in search of a ford for miles above and below the camp by the broken bridge, discovered a practicable crossing somewhere among the hills to the west of Leeds, and forced a passage with sixty horsemen in despite of the efforts of the enemy on the left 279bank. Having demonstrated the possibility of a crossing at this point Lisois returned to Pontefract; and under his guidance the whole army passed the Aire, and then wheeled round towards York through the difficult country which borders the great plain of the Ouse. As the army drew near to York, news came that the Danes had evacuated the city, so the king divided his force, sending one detachment to occupy and repair the ruined castles, and another to the Humber to keep the Danes in check. But he himself had other work to do, and did not enter York at this time.

It would seem that the Norman passage of the Aire, hazardous as it had been, had really demoralised the Northumbrian insurgents and their Danish allies. The latter, as we have seen, fell back on the Humber at once without striking a blow; the mass of the native English under arms would seem to have retired simultaneously among the hills of western Yorkshire, for the Conqueror now turned to their pursuit and to the definite reduction of the inhospitable land. With grim determination he worked his way along the wooded valleys which intersect the great mountain chain of northern England, and deliberately harried that region so that no human being might find the means of subsistence there. Resistance isolated and ineffectual he must have met; but now for once submission brought no favour, and those who perished in the nameless struggles in which 280despairing men flung themselves hopelessly upon the line of his inexorable march, underwent a shorter agony than remained for those who survived to see their homes, with all their substance, smouldering in the track of the destroying army. But the spirit was soon beaten out of the ruined men, and without fearing surprise or ambush William could divide his army still further and quicken the dismal process of destruction. Soon his soldiers were scattered in camps over an area of a hundred miles, and the north and east of Yorkshire underwent the fate which the Conqueror in person had inflicted on the West Riding. Before Christmas it is probable that the whole land from the North Sea to Morecambe Bay had become with the rarest exceptions a deserted wilderness.

The harrying of Yorkshire is one of the few events of the kind in regard to which the customary rhetoric of the medieval chronicler is only substantiated by documentary evidence. From the narratives of Ordericus Vitalis and Simeon of Durham alone, we should gain a fair impression of the ghastly reality of the great devastation, but a few columns of the Domesday survey of Yorkshire, where the attempt is made to estimate the result of the havoc for the purposes of the royal treasury, are infinitely the more suggestive. On page after page, with deadly iteration, manor after manor is reported “waste,” and even in the places where agricultural life had been re-instituted, 281and the burned villages rebuilt, the men who inhabited them formed but pitiful little groups in the midst of the surrounding ruin. As to the fate of the individuals who had fled before King William’s army, in the fatal December, no certain tale can be told. Many sold themselves into slavery in return for food, many tried to make their way southward into the more prosperous midland shires; the local history of Evesham Abbey relates how crowds of fugitives from the districts visited by the Conqueror in this campaign thronged the streets of the little town, and how each day five of six of them, worn out by hunger and weariness, died, and received burial by the prior of the monastery. Many no doubt tried to keep themselves alive in the neighbourhood of their old homes until the rigour of the winter had passed away; but fifty years later it was well remembered in the north how the bodies of those who were now overtaken by famine lay rotting by the roadsides. Even so late as Stephen’s time, a southern writer, William of Malmesbury, tells us how the fertile lands of the north still bore abundant traces of what had passed during the winter of 1069.

The festival of Christmas caused a short break in the grim progress of King William. His work was not by any means completed in the north; the Danes were still in the Humber; Chester remained in virtual independence. And so the regalia and royal plate were brought from the 282treasury at Winchester, and the Christmas feast was held at York with so much of the traditional splendour as the place and occasion permitted. The ceremony over, the campaign was resumed, and in the New Year the Conqueror set out to hunt down a body of Englishmen who seem to have entrenched themselves among the marshes which then lay between the Cleveland hills and the estuary of the Tees.[217] The rebels, however, decamped by night on hearing of the king’s advance, and William spent fifteen days by the Tees, during which time Earl Waltheof made his submission in person and Gospatric sent envoys who swore fealty on his behalf. Gospatric was therefore restored to his earldom, and William returned to York, keeping to the difficult country of the East Riding in preference to the Roman road which led southward from the Tees near Darlington down the plain of the Ouse.[218] It is probable that William chose this route with the object of hunting down any scattered bands of outlawed Englishmen which might have hung together thus far in this inaccessible region; but his force suffered severely through the cold, many of the horses died, and on one occasion he 283himself lost his way and became separated from his army with only six companions for an entire night. York, however, was reached in safety at last, and the reduction of Northumbria was accomplished.

It was now possible to enter upon the final stage of the campaign, and, after making the arrangements necessary for the safety of York, William set out on the last and most formidable of the many marches of this memorable winter, towards the one important town in England which had never submitted to his rule. Chester still held out in English hands, and apart from its strategical importance the citizens of the great port had definitely attracted King William’s attention by the part which they had played in the recent siege of Shrewsbury. His hold on the north would never be secure until he had reduced the town where Irish Vikings and Welsh mountaineers might at any time collect their forces for an attack upon the settled midlands. On the other hand, the geographical difficulties in the way of a direct march from York to Chester were enormous. From the edge of the plain of York to the Mersey Valley, the altitude of the ground never descends to a point below 500 feet above sea level; and, since the Roman highway from York to Manchester had fallen into ruin, no roads crossed this wild country except such tracks as served for communication between village and village. But a more serious cause of 284danger lay in the fact that the army itself now began to show ominous symptoms which might easily develop into actual mutiny. The strain of the protracted campaign was telling upon the men; and the mercenary portion of the army, represented by the soldiers from Anjou, Brittany, and Maine, began to clamour for their discharge, complaining that these incessant marches were more intolerable than even the irksome duty of castle guard. The Conqueror in reply merely declared that he had no use for the cowards who wished to desert him,[219] and, trusting himself to the loyalty of his own subjects in the army, he plunged straightway into the hills which separate the modern counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire. Part at least of the route now followed at the close of January must have lain through districts which had been swept bare of all provisions in the great harrying of December; and the army was at times reduced to feed on the horses which had perished in the swamps, that continually intercepted the line of advance. The storms of rain and hail which fell at this time were considered worthy of mention in the earliest account of the march which we possess, and we can see that nothing but the example of King William’s own courage and endurance held the army together and brought it down in safety into the Cheshire plain. Chester would appear to have surrendered 285without daring to stand a siege, and with its submission, guaranteed as usual by the foundation of a castle,[220] the Conqueror’s work was done at last in the north. From Chester he moved to Stafford, where another castle was raised and garrisoned, and then marched directly across England to Salisbury, at which place the army was disbanded, with the exception of the men who had protested against the present expedition and were now kept under arms for forty days longer as a mark of the king’s disfavour.

In the meantime, by a skilful piece of diplomacy, William had been insuring himself against active hostility on the part of the Danish fleet. Earl Asbiorn and his associates had taken but little gain as yet from their English adventure; and the earl proved very amenable when a secret embassy came to him from the king, promising him a large sum of money and the right of provisioning his men at the expense of the dwellers along the coast for the remainder of the winter, on the sole condition that he should keep the peace towards the royal troops thenceforward until his departure. The earl, thus made secure of some personal profit, agreed to the terms, and until the spring was far advanced, the Danish ships still hung in the English waters.

286The harrying of Northumbria, the most salient event of these twelve months of ceaseless activity, was a measure which it would be impossible to justify and impertinent to excuse. It was the logical result of the opposition of an irreconcilable people to an inflexible conqueror. After the battle of Hastings had shattered the specious unity of the old English state, each of its component parts might still have secured peace by full submission, or honour by consistent and coherent resistance; the men of Northumbria took the one course which was certain to invite disaster, nor, terrible as was the resultant suffering, can we say that vengeance was undeserved. War in the eleventh century was at best a cruel business, but we cannot fairly accuse the Conqueror of deliberately aggravating its horrors without the impulse of what he must have regarded as necessity. He had to deal with a people whom he could not trust, who had sworn submission and had broken their oaths, and the means at his disposal were few. He could not deport the population of Northumbria as Cromwell was to deport the native Irish under not dissimilar circumstances; his Normans were too few as yet to garrison effectively all the wild land between the Humber and the Scottish border. The one course which remained to the Conqueror was for him to place the rebels beyond the possibility of revolting again, and he followed this course with terrible success. And it was on this 287account—that Northumbria was wasted, not in the heat of wars, but deliberately, at the bidding of political necessity—that the act seemed most dreadful to the chroniclers who have described it. Men were only too well accustomed to the sight of ruined villages, of starving women and children; but these things seemed less terrible as the work of Scotch and Danish freebooters than as the conscious intention of the crowned king of the land. Nor must we forget that we do not know how far King William was really sinning against the current military practice of his time. The monastic chroniclers, whose opinion of the case commends itself to us in virtue of its humanity, were men brought by the fact of their vocation to a clearer sense of the value of the individual life than that possessed by the lay world around them. We know what Ordericus Vitalis thought of the great harrying, perhaps even what William of Poitiers, the Conqueror’s own chaplain, thought of it, but we do not know how it appeared to William Fitz Osbern or Roger de Montgomery.

According to his approved custom, the Conqueror kept the Easter following these events at Westminster, and the feast was attended by three papal legates of high rank whose presence marks the beginning of the ecclesiastical reformation which we shall have to consider in its place as the counterpart of the legal and administrative changes produced by the Norman Conquest. In the meantime, however, the broken national 288party was gathering its forces for a last stand, and the focal point of the English resistance shifts to the extreme east of the land.

At each stage in the Norman Conquest there is always one particular district round which the main interest centres for the time, the operations of war elsewhere being of subsidiary importance. It was the men of Kent and Sussex who bore the brunt of the first shock of the invasion; it was the men of the north who held the field in 1069, and now, in the last period of English resistance, our attention is concentrated on the rectangular tract of land which lies between Welland, Ermine Street, Ouse, and Wash. Even at the present day, after eight centuries of drainage, it is not difficult to reconstruct the geographical features which in 1070 made the Fenland the most inaccessible part of England south of the Humber. Except for a narrow tract north of Huntingdon and St. Ives, no part of this district rises to one hundred feet above sea-level, and in great part it was still covered with the swamps and meres of stagnant water which gave to the eastern half of this region the name of the Isle of Ely. In so far as cultivation had already extended into this inhospitable quarter, it may fairly be set down to the credit of the five great abbeys of Peterborough, Thorney, Crowland, Ramsey, and Ely, which dominated the fens and round which the events of the campaign of 1070 arrange themselves.

Abbot Brand of Peterborough, whose recognition 289of Edgar the Etheling as king had so deeply moved the Conqueror’s wrath at the time of his coronation, had died on November 27, 1069.[221] At this moment King William was in the thick of his Northumbrian difficulties, and it does not appear that any appointment to Peterborough was made until the quieter times of the following spring. In or before May, however, the abbey was given to a man whose selection for the post proves that the king had received warning of the coming disquiet in the east. Thorold of Fécamp, abbot of Malmesbury, had probably made himself useful in north Wiltshire while William was engaged beyond the Humber, for the reputation for militant severity which he had created in the south was the reason for his translation to a post of danger in the Fenland. “By God’s splendour,” said King William, “if he is more of a knight than an abbot I will find him a man who will meet all his attacks, where he can prove his valour and his knighthood and practise the art of war.”[222] The man in question was no other than the famous Hereward, and Thorold was not long before he saw traces of his handiwork.

The amount of authentic fact which we know about Hereward is in very small proportion to the great mass of legend which has gathered round his name. His parentage is quite unknown, but there are several incidental entries in Domesday 290which connect him with the western edge of the Fenland and which all occur in the Lincolnshire portion of the survey. From these entries we learn that Hereward had been a tenant of two of the great Fenland abbeys, namely Crowland and Peterborough, and we also gather that the former house had found him an unsatisfactory person with whom to have dealings. The jurors of Aveland Wapentake in Lincolnshire told the Domesday commissioners that Abbot Ulfketil of Crowland had let the abbey’s estate in the vill of Rippingale to Hereward on terms to be arranged mutually year by year, but they add that the abbot took possession of the land again before Hereward fled from the country because he did not keep to his agreement.[223] On the other hand, Hereward was seemingly still in the possession of the lands which he held of Peterborough abbey at the moment when his name first appears in the national history.

At some time in the course of May, but before Abbot Thorold had taken possession of his abbey, the Danish fleet, of which we have heard nothing since the previous year, sailed up the Ouse to Ely. Thus far its leaders would seem to have kept the agreement which they had made with King William after his capture of York, and the fact that they now appear as taking the offensive once more is probably explained by a statement in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that King Swegn 291of Denmark had come in person to the Humber.[224] The men of the Fenland were clearly expecting a Danish reconquest of England, and on the appearance of Earl Asbiorn at Ely they joined him in great numbers. Among them, and probably at their head, was Hereward, and the first fruit of the alliance was a successful raid on the wealthy and unprotected monastery of Peterborough. The monks received just sufficient warning of approaching danger to enable them to send an urgent message to Abbot Thorold, asking for help, and also to hide some of the more precious treasures of their house, and then at mid-day Hereward and his gang were on them. They came by boat, for even at this date there were canals which connected the Ouse at Ely with the Nene at Peterborough, and began to clamour for admission to the abbey.[225] But the monks had closed their doors and defended them stoutly, so that Hereward was driven to burn the houses which clustered round the abbey gate in order to force 292an entrance. Incidentally the whole of Peterborough was burned down, with the exception of the church and a single house, but the outlaws had got inside the monastery. The monks begged them to do no harm, but, without heeding, they burst into the church, seized all the movable articles of value on which they could lay their hands, and tried to tear down the great rood cross. To the clamours of the monks around them they shouted that they did it all for the good of the church, and as Hereward was a tenant of the abbey the monks believed him. Indeed, Hereward himself in after years declared that he had been guided in this matter by the best intentions, for he believed that the Danes would beat King William and he thought that it would be better that the treasures of the church should remain in the hands of his friends for a little while, than that they should fall for ever into the possession of the Frenchmen.

So the monks were scattered and the wealth of the Golden Borough was carried off to Ely and handed over to the Danes, who do not seem to have shared Hereward’s sentiments with regard to its ultimate destination. Among the captives who were carried off from Peterborough was Ethelwold, the prior, who, in hope of better days, devoted himself secretly to the recovery of the relics contained in the jewelled shrines which formed the most valuable part of the plunder that had just been taken. With this 293object in view, he deliberately set himself to win the favour of the despoilers of his home, and succeeded so well, that the Danes committed their treasure to his custody, and promised him a bishopric in Denmark if he chose to return with them. Being a discreet man, he pretended to comply with their wishes, and in the meantime possessed himself of the tools which were necessary for the abstraction of the relics. And on a certain day, while the Danes were holding a great feast, to celebrate the winning of so great a treasure at so small a cost, Ethelwold took his tools and set to work, beginning his operations on the reliquary which he knew to contain the arm of St. Oswald. To prevent interruption he placed two servants on guard, one in the house where the Danes were feasting, and the other midway between the latter place and the scene of his own labours. The task progressed without greater difficulty than was to be expected, although one of the chests was so tightly clamped with iron that Ethelwold would have abandoned it had he not trusted in God and St. Oswald. At last the relics were all secured and hidden temporarily in the straw of the prior’s bed, he being careful to replace the gold and silver fittings of the shrines as they were before. But at the critical moment the Danes broke up to go to vespers and Ethelwold was in imminent danger of being taken, in which event it is probable that his pious zeal would have been rewarded with the crown of 294martyrdom. But, without leaving his room, the prior, who was covered with sweat and very red from his labour in the heat of a June afternoon, washed his face in cold water and went out to his captors as if nothing had happened, and they, who we are told reverenced him as a father, flocked round him but asked no inconvenient questions. And on the following day he sent his two servants to Hereward—because his comrades were infesting all the water-ways—under the pretence that they wished to fetch something from Peterborough, but in reality they went to the nearer monastery of Ramsey and gave the relics into the charge of the abbot of that place.

At this point the adventures of Prior Ethelwold touch the current of the general history. King William, in order, presumably, to divide the insurgent Englishmen from their Danish allies, made a treaty with Swegn of Denmark, by which his subjects were to be allowed to sail for their fatherland without hindrance and in possession of all the spoil they had gained in the course of the past months. They took advantage of the offer, but gained little by it in the event, for a great storm arose which scattered their ships, and the last we hear of the treasures of Peterborough is their destruction, in a nameless Danish town, in a great fire which arose through the drunkenness of their guardians. In the meantime, Ethelwold, his troubles over, collected his fellow-monks and came back to Peterborough, where 295they found Abbot Thorold, and restored the services which had been suspended during the recent disturbances. One unexpected difficulty indeed manifested itself: the Ramsey people refused to give up the relics which had been entrusted to their care in the moment of peril. But the abbot of Ramsey was soon brought into a better mind; the sacristan of the monastery received a supernatural intimation that his house was acting unjustly, and Thorold of Peterborough threatened to burn Ramsey abbey to the ground unless the relics were given back. And so the heroic efforts of Ethelwold were not frustrated of their purpose.

So quickly had events moved that only one week had elapsed between the coming of Hereward to Peterborough and the departure of the Danish fleet. But an entire year had yet to pass before the Isle of Ely was finally cleared of its rebel garrison. It does not seem that the withdrawal of the Danes made any difference to the occupation of Ely by the English, and during the winter of 1070 the Isle became a gathering point for the last adherents of the broken national party. Very few of them were left now. Edgar, their nominal head, was living in peace with King Malcolm of Scotland; Waltheof, the last representative of the Danish earls of Northumbria, was at this moment in enjoyment of an earldom in the midlands which there is every reason to believe included the Isle of Ely itself. On the other hand, Edwin and Morcar now finally took 296their departure from William’s court, and raised the last of their futile protests against the Norman rule.

Hitherto inseparable, on this occasion the brother earls took different courses, and the result was disastrous to both of them. Morcar joined the outlaws in Ely; Edwin struck out for the Scotch kingdom, and from our meagre information about his last months it would seem that he had in view some great scheme of reviving once more the old friendship between his house and the Welsh princes and of supporting the combination with Scotch aid. But fate overtook him before he had time to give another exhibition of his political worthlessness, and the circumstances of his end were tragic and mysterious. Three brothers, who were on terms of intimacy with him and were attending him in his wanderings, betrayed him to the Normans, and in attempting to escape, his retreat was blocked by a river swollen at the moment by a high tide. On its bank the last earl of Mercia turned at bay, and with twenty horsemen at his side made a desperate defence until the whole band was cut down; Edwin himself, it would appear, falling by the hands of the three traitors of his household. His head was cut off and the same three brothers brought it to King William in the expectancy of a great reward. But the Conqueror on the spot outlawed them for their treason to their lord, and shed tears of grief over Edwin’s head; for the 297handsome, fickle young earl, with all his faults, had really won the love of the grim sovereign from whom he had thrice revolted.[226]

Edwin fell through treachery, but he met his death in the sight of the sun; another fate remained for his brother and for those of his associates whose end is known to us. The cause of the defenders of Ely was hopeless from the outset. Their revolt was a hindrance to the orderly conduct of the Anglo-Norman government, but a band of outlaws in the fenland could do little to affect the course of events elsewhere; Ely commanded no great road or river, and its Isle was too small an area to support an independent existence apart from the rest of the land. Its reduction was only a question of time, complicated by the geographical difficulties of the district. It was necessary that all the waterways leading from the fens to the open sea should be blocked, and this implied the concentration of a considerable number of ships and men-at-arms along the Great and Little Ouse. The siege of a quarter of Cambridgeshire demanded a greater expenditure of men and money than that of a single town or castle; but Hereward and his friends in due time were driven back on Ely itself, from which their raiding parties would make occasional descents upon the neighbouring villages. 298The Conqueror fixed his headquarters at Cambridge, some fifteen miles from Ely, and his main attack was directed at the point where the Ouse is crossed by an ancient causeway near the village of Aldreth. But even from the latter place there remained some six miles of fen to be crossed before Ely itself could be reached, and we are told on good authority that William caused a bridge, two miles long, to be built on the western side of the Isle.[227]

The legendary accounts of the exploits of Hereward tell many tales of the struggle which raged before the Norman army had pierced the natural defences of Ely, but we cannot be sure of the exact means by which the place was finally reduced. One stream of tradition assigned the fall of the Isle to the treachery of the abbot and monks of Ely, and, although the authority for such a statement is not first-rate, it has commonly been accepted as representing the truth of the matter.[228] It is at least certain that the position in which the monks of Ely found themselves was undesirable at the best. The conduct of Hereward and his men at Peterborough proves them to have been no respecters of holy places, and if the abbey bought immediate safety by conniving at the deeds of the outlaws in its neighbourhood, it ran the risk of the ultimate confiscation of its lands when King William had restored order. Small blame should rest upon 299the abbot if he broke through the dilemma in which he was placed by assisting the Conqueror in the reduction of the Isle. But whatever the immediate cause of the fall of Ely, a large number of its defenders fell into William’s hands and many of them received from him such measure as twenty years before he had dealt to the men of Alençon. Some were blinded or otherwise mutilated and allowed to go free, others were thrown into prison. Earl Morcar himself was sent into Normandy a prisoner and committed to the charge of Roger de Beaumont[229]; the other captives of note were scattered over the country in different fortresses. But Hereward, who in all our authorities stands out as the leader of the resistance, escaped through the marshes and a small part of his band got clear of the Isle in his company.[230]

Whatever the recent behaviour of the monks of Ely may have been, the abbey was constrained to buy the king’s peace at a heavy price. Seven hundred marks of silver were originally demanded by the Conqueror, but the money was found to be of light weight, and three hundred marks more were exacted before the abbot and monks were reckoned quit by the king’s officer. Moreover, the very precincts of the abbey were invaded to find the site for a castle to command the southern fenland: King William himself having chosen the 300ground during a flying visit which he had paid to Ely one day while the monks were seated at dinner. The building of the castle, by a Norman interpretation of the Anglo-Saxon duty of burhbot, was laid upon the men of the three adjacent counties of Cambridge, Huntingdon, and Bedford, and it was garrisoned when built by a body of picked knights. Another castle at Aldreth commanded the eastern approaches to the Isle.[231] On the other hand, it would be some compensation for these disturbances that within four years from the fall of Ely, and in the lifetime of Abbot Thurstan, King William decreed a formal restitution to the abbey of all the lands of which it had unjustly been despoiled in recent years.[232] Now that no further danger was to be apprehended from the nationalist proclivities of the monks of Ely, there was no reason why th e abbey should not be suffered to enjoy its ancient possessions in peace; but the record of the plea which followed the Conqueror’s writ directing restitution proves that many of the greater people of the land, including the archbishop Stigand and Count Eustace of Boulogne, had been committing wholesale depredations on the estates of St. Ethelthryth.

The subsequent fate of Hereward is a matter of utter uncertainty; with his flight across the marshes of Ely he vanishes into the night which has engulfed the entire class to which he belonged, the smaller native land-owners of King Edward’s day. Two lines of tradition were current in later years about the manner of his end. According to the more dramatic narrative, Hereward became reconciled to the Conqueror, accompanied him in the Mancel campaign of 1074, married a noble and wealthy Englishwoman, and fell at last, before overwhelming odds, at the hands of a number of Normans, whose feud he would seem to have provoked in the wild days of his outlawry.[233] In the other story, Hereward still receives King William’s favour and marries the same English lady as in the former legend, but he dies at last in peace after many years in the quiet possession of his father’s lands.[234] The choice which we may make between these divergent traditions will largely be guided by inference from more truly historical sources of information. It is very probable that Hereward made his peace with King William—both traditions agree upon this point; and that casual expression in the narrative of the sack of Peterborough, that Hereward “in after time often told the monks that he had done all for the best,” proves at least that there had been a period after the troubles of 1071 in which Hereward had been on terms of peaceful intercourse with his monkish neighbours. So too the coincidence of both lines of tradition with regard 302to his marriage is in favour of its probability, but the negative evidence of Domesday Book compels us to put a period to his life before the winter of 1085. In no part of England did a more numerous body of native thegns hold land at the latter date than in Hereward’s own county of Lincoln, but Hereward’s name is not written among them, and the lands which he had held of Peterborough abbey had been let to a stranger. But if the Hereward legend is not consistent with itself, there is a more significant discrepancy between the part which its subject plays in recorded history and his position as a hero of romance. It is at least certain that the man must have been something more than the vulgar freebooter who appears in the story of the ruin of Peterborough. To him we may safely credit the long defence of the Isle of Ely, and we may feel confident that that defence was accompanied by deeds of gallantry round which minstrel and gleeman might weave their fabric of legend and marvel. Hereward, after all, in literature, if not in fact, is the English hero of the Norman Conquest. A native annalist might express his bitter regret for the tragedy of King Harold, the common folk of England might turn Earl Waltheof into an uncanonised saint, but Hereward was removed by no great chasm of rank from the humble people who made his deeds their story. And it is not a small thing that the tale of the resistance to the Norman Conqueror, inglorious 303as much of it had been, should end with the name of a man in whom the succeeding generations might see a true champion of the independence of the beaten race.

Penny of Swegn Estuthson

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content