Search london history from Roman times to modern day

The conquest of England had exalted William of Normandy to a position of dignity and influence far above all his fellow-vassals of the French crown, it had renewed the lustre of the fame which the Norman race had won in its earlier conquest of southern Italy, but it did not mean an unqualified gain to the Norman state, considered merely as a feudal power. The process which had turned the duke of the Normans into the king of the English had meant the withdrawal of Normandy from the feudal politics of France for four years, and in that interval certain changes of considerable importance had taken place within the limits of the French kingdom. The Angevin succession war was now over; Fulk le Rechin had his brother safely bestowed in prison and could begin to prove himself the true heir of Geoffrey Martel by renewing the latter’s schemes of territorial aggrandisement. King Philip of France had reached an age at which he was competent to rule in person, and it was inevitable that the enmity between Normandy and France should become deeper and more persistent now that William had attained to a rank which placed him on an equality with his suzerain, and could 305employ the resources of his new kingdom for the furtherance of any designs which he might form upon the integrity of the royal demesne. More important than all, Count Baldwin of Flanders had died in 1067, and events were in progress which for twenty years placed the wealthy county in steady opposition to the interests of the Anglo-Norman state.

Between 1067 and 1070 Flanders was under the rule of Count Baldwin VI., the eldest son of Baldwin of Lille, who had greatly increased his borders by a marriage with Richildis, the heiress of the neighbouring imperial fief of Hainault. The counts of Flanders made it a matter of policy to transmit their inheritance undivided to the chosen heir, and Robert, the younger son of the old Count Baldwin, before his father’s death had secured himself against his ultimate disinherison by marrying Gertrude, widow of Florent I., count of Holland, and assuming the guardianship of her son Theodoric. On the death of Baldwin VI., the ancestral domain of Flanders descended to his eldest son, Arnulf, who was placed under the wardship of his uncle Robert, while Hainault passed to Baldwin, the second son, under the regency of his mother Richildis. The two regents were on bad terms from the start, but Robert at the time was hard pressed to maintain his position in Holland, and Richildis soon got possession of Arnulf, the heir of Flanders, and ruled there in his name. But her overbearing conduct rapidly 306made her unpopular in the county, and Robert was soon invited to invade Flanders and reign there in his own right. He accepted the invitation, and Richildis thereupon hired King Philip of France to support her with an army, and offered her hand and her dominions to William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford. The earl, like a good knight-errant, accepted the adventure and hastened to the succour of the lady with the full assent of his lord King William, but fell into an ambush laid by his enemy Robert, at Bavinkhove, near Cassel, and perished there together with Arnulf his ward. Richildis maintained the struggle for a short time longer with the aid of troops supplied by the prince-bishop of Liège; but on their defeat near Mons, followed a little later by the surrender of Terouenne, the ecclesiastical capital of Flanders, she retired into the monastery of Maxines, and Robert, who is generally described in history as the “Frisian” from the name of his earlier principality on the shores of the Zuyder Zee, had the permanent possession of Flanders thenceforward.

The enterprise of William Fitz Osbern meant the dissolution of the alliance between Normandy and Flanders, which had been founded by the Conqueror’s marriage in 1053. It was true that French as well as Norman troops had been involved in the disaster at Bavinkhove, but William deliberately refused to make peace with Robert by recognising his right to Flanders, and threw 307him into the arms of the king of France by maintaining the claims of Baldwin, the brother of the dead Arnulf. The close friendship which this policy produced between France and Flanders for a time may suggest that William for once subordinated questions of state to personal feeling, but his own relations with a former king of France may have taught him that the alliances which a French monarch founded with one feudatory on a common hostility towards another were not likely to be very strong or permanent. It was not long after these events that King Philip threw away his Flemish connections by the unprovoked capture of Corbie, preferring, perhaps wisely, a definite territorial gain to a hazardous diplomatic understanding; and when Robert the Frisian, in 1085, at last tried to take the offensive against William, he found support, not in the French monarchy, but in the distant powers of Norway and Denmark.[235]

More dangerous than the open hostility of Flanders were the symptoms of disaffection which at this time were beginning to show themselves in the Norman dependency of Maine. Fortunately for William, the county had kept quiet during his occupation with the affairs of England, and the revolt which we have now to consider occurred at a time when he could give his full attention to the work of its reduction. The 308nationalist party in Maine had only been suppressed, not crushed, by the conquest of 1063, and after some five years of Norman rule their hopes began to revive, fomented probably by external suggestion on the part of Count Fulk of Anjou. There were in the field two possible claimants, both connected by marriage with the line of native counts: Azo, marquis of Liguria, husband of Gersendis, the eldest sister of the Herbert whose death in 1063 had led to the Norman occupation, and John de la Flèche, who had married Paula, the youngest of Herbert’s three sisters. The seigneur of La Flèche was an Angevin lord, but he took the Norman side in the war which followed, and the nationalists made their application to the marquis of Liguria, who appeared in Maine with Gersendis his wife and Hugh their son, the latter being received as the heir of the county.[236] Azo had brought with him great store of treasure from his Italian lordship, with which he secured a recognition of his son’s claims from great part of the Mancel baronage, but upon the failure of his supplies his supporters began to fall away, and he soon retired in disgust beyond the Alps, leaving behind his wife and son to maintain the family cause under the guardianship of Geoffrey of Mayenne.

Thus far the Mancel revolt had run the normal course of its kind, but a more interesting development 309followed.[237] Shortly after the departure of Azo the citizens of Le Mans, rejecting the leadership of their baronial confederates, broke away on a line of their own which gives them the distinction of anticipating by some twenty years the movement of municipal independence which in the next generation was to revolutionise the status of the great cities of Flanders and northern France. The men of Le Mans formed themselves into a “commune”[238]; that is, a civic republic administered by elective officers and occupying a recognised legal position in the feudal hierarchy to which it belonged. Had this association persisted, the citizens in their collective capacity might have held their city of the duke of Normandy or the count of Anjou, but they would have enjoyed complete independence in their local government and no principle of feudal law would have prevented them from appearing, still collectively, as the lord of vassals of their own. We do not know whether they may have been prompted to take this step by news of Italian precedents in the same direction, but the formation of a commune raised the revolt at a bound to the dignity of a revolution. The citizens, as was usual in such cases, united themselves in an oath to maintain their constitution and they compelled 310Geoffrey of Mayenne and the other barons of the neighbourhood to associate themselves in the same. Herein lay the seeds of future trouble, for Geoffrey of Mayenne, a typical feudal noble, had no liking for municipal autonomy, and it was largely his oppression as the representative of Azo and his heir which had stung the citizens into this assertion of their independence.

At the outset all went well with the young republic. We hear rumours of various violations of accepted custom, of the death penalty inflicted for small offences, and of a certain disregard for the holy seasons of the church; but the citizens were able to enter without immediate mishap upon the work of reducing the castles which commanded the country around. The commune of Le Mans did not live long enough to face the problem of welding a powerful rural feudality into a coherent city state, and its overthrow, when it came, came suddenly and disgracefully. Some twenty miles from Le Mans, the castle of Sillé was being held by Hugh its lord against the commune, and the men of the capital called out a general levy of their supporters within the county to undertake the siege of the fortress. A considerable body of men obeyed the summons, and the communal army set out for Sillé with Arnold, bishop of Le Mans, marching at its head. Hard by the castle the army from Le Mans was joined by Geoffrey of Mayenne with his tenants; but Geoffrey felt the incongruity of joining with a host of 311rebellious burghers in an attack on the castle of a fellow-noble, and he secretly entered into communications with Hugh of Sillé. Whether the rout of the civic host which occurred on the following day was the result of Geoffrey’s treason cannot now be decided, but a sudden sally on the part of the garrison threw the besiegers into confusion, and, although they recovered themselves sufficiently to maintain the fight, they were finally scattered by a report that Le Mans itself had fallen into the enemy’s hand. Great numbers of them perished in the panic which followed, more by the precipitancy of their flight than by the efforts of the men of Sillé, and Bishop Arnold was among the prisoners.

Within the capital all was confusion. The cause of the commune had been hopelessly discredited, and there was treachery within the city as well as in the camp by Sillé. The castle of Le Mans was occupied in the nationalist interest by Gersendis of Liguria, who, immediately upon the retreat of her elderly husband to Italy, had become the mistress of Geoffrey of Mayenne. But Geoffrey, after his conduct at Sillé, did not venture to return to the capital, and Gersendis, unable to endure her lover’s absence, began to plot the surrender of the castle to him. Her object was soon gained, and a fierce struggle raged for many days between the citizens and Geoffrey of Mayenne, now in the possession of their fortress. Betrayed and desperate, the men of Le Mans appealed 312for help to Fulk of Anjou, and pressed on the siege with such fury that Geoffrey was driven to make his escape by night. On Fulk’s arrival the castle surrendered to him, and was dismantled, with the exception of such of its fortifications as could be turned to the general defence of the city against the greater enemy who was already on the way.

Quickly as events seem to have moved, there had yet been time for news of the revolt to be brought to King William in England, and the messenger of evil had been no less a person than Arnold bishop of Le Mans himself. Long before William’s army had been set in motion Arnold had returned to Le Mans to play, as we have seen, a somewhat ignominious part in the catastrophe at Sillé. Meanwhile William had gathered a force, which is especially interesting from the fact that in it for the first time Englishmen were combined with Normans in the service of the lord of both races beyond the sea. Englishmen in the next generation believed that it was their compatriots who did the best service in this campaign, and William of Malmesbury thought that though the English had been conquered with ease in their own land yet that they always appeared invincible in foreign parts.[239] On the present occasion, however, there was little call for feats of arms. William entered Maine by the Sarthe Valley and besieged Fresnay, whose lord, Hubert, was soon driven by the harrying of his lands to surrender 313Fresnay itself and the lesser castle of Beaumont lower down the river. Sillé was the next point of attack, but Hugh of Sillé made his submission before the investment of his castle had begun, and William moved on southward towards Le Mans. After the strife and confusion of the past months men were everywhere disposed to welcome the King as the restorer of peace, castles were readily surrendered to him, and the way lay open to the distracted capital. Here too, after a brief delay, he was received without opposition, but the men of Le Mans, before they surrendered the keys of the city, obtained from the king a sworn promise that he would pardon them for their revolt, and would respect their ancient customs and the independence of their local rights of jurisdiction.[240] The commune of Le Mans ceased to exist, but in its last moments it had shown itself strong enough to win an act of indemnity from its formidable conqueror, and to guard itself against the possible consequences of a feudal reaction.

The war now entered upon another phase. Count Fulk was little minded to forego the position he had won in Le Mans as the protector of its commune, and, but for the unwonted strength of the Anglo-Norman army, it is likely enough that he would have made some effort to oppose William’s march to the city. As it was, however, he contented himself with turning upon John 314de la Flèche, William’s leading Angevin adherent, who immediately appealed to his ally for help. William at once despatched a force to his assistance under William de Moulins and Robert de Vieux Pont, a move which had the effect of widening the area of hostilities still further. Fulk proceeded to the siege of La Flèche, and called to his assistance Count Hoel of Brittany.[241] The combined Breton and Angevin host would be far superior to any force which William’s lieutenants had in the field in that quarter; and at the head of a large army, now as formerly composed of English as well as Norman troops, he hastened to La Flèche in person and everything betokened a pitched battle of the first class. But, at the supreme moment, an unnamed cardinal of the Roman Church, together with some pious monks, intervened in favour of peace, and within the circle of the Norman leaders Counts William of Evreux and Roger of Montgomery were of the same mind. Various conferences were held to discuss the conditions of a possible settlement, and at last, at Blanchelande, just outside the walls of La Flèche, a treaty was concluded.[242] Now, as ten years earlier, Robert of Normandy was selected as count of Maine, and to him Fulk of Anjou 315released the direct suzerainty which he claimed over the barons of the county, together with all the fiefs which were Robert’s marriage portion with Margaret, his affianced bride in 1061. Robert, in return, recognised Fulk as the overlord of Maine, and did homage to him in that capacity. William promised indemnity to those Mancel barons who had taken the Angevin side in the late war, and Fulk was formally reconciled to John de la Flèche, and the other Angevin nobles who had leagued themselves with the king of England.

The treaty was in effect a compromise. All the immediate advantage, it is true, lay on the Norman side: the heir of Normandy was now the lawful count of Maine, and Robert’s countship meant the effective rule of William the Conqueror, who even appropriated his son’s title and in solemn documents would at times add to his Norman and English dignities the style of “Prince of the men of Maine.” Yet, on the other hand, the formal recognition of the Angevin overlordship was no small thing. It gave to succeeding counts of Anjou a vantage ground which they did not neglect. The line which separated suzerainty from immediate rule, clear enough in law, would rapidly become indistinct when a strong prince like Fulk the Rechin was the overlord, and a feckless creature like Robert Curthose the tenant in possession. More than sixty years were to pass before a count of Anjou became the immediate 316lord of Maine, but the seeds of such a development were laid by the treaty of Blanchelande.

In the period which follows the suppression of the fenland rising of 1070, the bulk of our historical information relates to the affairs of the Conqueror’s continental dominions. But in English history proper the time was one of crucial importance. Its character was not such as to invite the attention of a medieval chronicler, eager to fill his pages with a succession of battlepieces: with the exception of the revolt of the earls in 1075, England was outwardly at peace from the flight of Hereward to the Conqueror’s death; but it is to this time that we must assign the systematic introduction of Norman methods of government, and the gradual reconciliation of the English people to the fact that they had thrown their last try for independence, and that for good or ill they must make the best of the permanent rule of their alien masters. A process of this kind, in itself largely subconscious, lay beyond the understanding of the best monastic annalist or chronicler, and we shall never know exactly in what light the great change presented itself to the peasantry of a single English village; but there are certain matters, more on the surface of the history, with regard to which we possess definite information, and which themselves are of some considerable importance.

Prominent among these last stands the question of the relations between the Conqueror and his 317unquiet neighbour, or, as William would probably have described him, his unruly vassal, Malcolm Canmore, king of Scots. The Scotch question had merely been shelved for a little time by the submission of 1068, and up to the Conqueror’s death there remained several matters in dispute between the kings, each of which might serve as a decent pretext for war if such were needed. In particular the English frontier on the north-west emphatically called for rectification from King William’s standpoint. Ever since the commendation of Cumbria to Malcolm I., in or about 954, the south-western border of Scotland had cut the English frontier at a re-entrant angle at a particularly dangerous point. From the hills which rise to 2000 feet along the boundary between Cumberland and Durham, the valley of the Tees affords a gradual descent to the fertile country which lies between the moors of the North Riding of Yorkshire and the hills of Cleveland. So long as Lothian remained part of the Bernician earldom, the strategical significance of Teesdale was to a great extent masked; no king of Scots could ravage the plain of north Yorkshire without facing the possibility that his country might be harried and his own retreat cut off by a counter raid from Bamburgh or Dunbar. But the cession of Lothian to Malcolm II. after the battle of Carham in 1018 materially altered the military situation, and but for the dissensions within the Scotch kingdom which followed Malcolm’s death, it is probable 318that Yorkshire during the Confessor’s reign would have received sharp proof of the danger which impended from the north-west.

Malcolm was succeeded by Duncan, the son of his sister by Crinan, lay abbot of Dunkeld; and on Duncan’s displacement by Macbeth, leader of the Picts beyond the Forth, the position of the new king was too unstable to allow him to interfere effectively on the side of Northumbria. Relying as he did on Highland support, Macbeth seems to have left Cumberland in virtual independence, and it has recently been proved that during some part of the first fifteen years of his reign Cumberland was largely settled by English thegns who seem to have regarded themselves as subject to Earl Siward of Northumbria.[243] On his part, Siward supported the party of Malcolm, Duncan’s son; but when, three years after Siward’s death, Malcolm had become king of Scots, the tide began to turn, and Cumberland became once more a menace to the peace of northern England.

The restoration of the son of Duncan to the throne of Scotland brought into importance the marriage relationship which existed between his line and the family which for a century had held hereditary possession of the Bernician earldom. The complicated relationships which united the local earls of Bernicia will best be illustrated in tabular form,[244] but the outline of the Northumbrian succession is fairly clear. Siward, although 319a Dane by birth, was connected by marriage with the great Bernician house, but on his death in 1055 the ancient family was dispossessed of the earldom in favour first of Tostig and then of Morcar. Their earldoms, however, were mere incidents in the general rivalry between the houses of Godwine and Leofric, and the attachment of the Northumbrians to their local dynasty is shown by the fact that, at the crisis of 1065, Morcar is found appointing Oswulf, son of Earl Eadwulf II., subordinate earl of Bernicia beyond the Tyne. Upon Oswulf’s murder his cousin Gospatric, as we have seen, bought a recognition of the family claims from the Conqueror; and it is not improbable that the latter, when making Gospatric his lieutenant in Northumbria, may have had in mind some idea of securing peace from the side of Scotland and conciliating the local sentiment of the north through an earl who inherited the blood of the ancient lords of Bamburgh and was near of kin to the king of Scots. The plan in the first instance failed through the defection of Gospatric in the summer of 1068, but the rapidity with which his restoration followed the submission which he tendered by proxy to William on the bank of the Tees at the close of 1069 is itself significant. In the interval created by Gospatric’s deposition there had occurred the disastrous experiment of the appointment of Robert de Comines. It was as important now as two years previously to prevent the men of 320Northumberland and Durham from making common cause with Malcolm of Scotland against the Norman government; and now as formerly Gospatric was the one man who could, if he chose, perform this work. But before another year had passed the precarious tranquillity of the north was again broken, and the Scotch danger reasserted itself in the acutest of forms.

We might gather from the table above referred to, alone, that Malcolm, by his English connections, would be the natural protector of any dispossessed natives who might choose to seek refuge at his court, and we have seen that Edgar the Etheling had twice been driven to escape beyond the Tweed. We possess no information as to the motives which induced Malcolm in the course of 1070 to break peace with King William. In his barbarian mind Malcolm may have conceived of himself as avenging the wrongs of his English friends by harrying the land from which they had been driven, or, more probably, the withdrawal of the Conqueror from the north may have seemed to him to open a safe opportunity for an extended plunder raid. Possibly he regarded his cousin Gospatric as having betrayed the cause of his people by doing homage to the Norman Conqueror, but whatever the immediate cause, he suddenly fell upon Northumbria by way of Cumberland and Teesdale, harried Cleveland and Holderness, and then turned back again upon the 321modern shire of Durham.[245] And it was while he was in the act of burning the town of Wearmouth that Edgar the Etheling, with his mother and sisters, accompanied by Marleswegn, Harold’s former lieutenant in the north, and other battered relics of the national party, landed from their ships in the harbour.[246] So long as the Danes under Earl Asbiorn had kept to the Humber, it would seem that the etheling had been content to drift about aimlessly with them, but their departure for Ely had driven him to seek refuge for a third time within two years at the Scottish court. Malcolm went down to the fugitives and assured them of a welcome in Scotland, whither they sailed off without delay, while he betook himself with renewed energy to his work of devastation.

For in the meantime Gospatric had been doing what he would consider to be his duty as the lawful earl of Bernicia: while Malcolm was harrying Durham, Gospatric was harrying Cumberland. The action taken by King Malcolm had for the time being destroyed all possibility of a coalition between Scot and Bernician, and, on the present occasion, Gospatric’s fidelity was unimpeachable, if his generalship was bad. He was successful 322in carrying off much booty to his fortress of Bamburgh, but he did nothing to check the Scot king’s depredations, and the news of what had been happening in Cumberland excited Malcolm to a state of fury, in which he committed the most appalling atrocities on the country folk of the region through which his northward march lay. Red-handed as he was, Malcolm on his return to Scotland found the English exiles in the enjoyment of his peace, and forthwith insisted that Margaret, the etheling’s sister, should be given to him in marriage. Some project of the kind had undoubtedly been mooted during the etheling’s earlier visits to Scotland, but Margaret felt a desire to enter the religious life; and nothing but the fact that the very existence of the fugitives lay at Malcolm’s mercy induced the etheling to give his consent to the union. The exact date of the ceremony is uncertain, but it may not unreasonably be placed in the course of 1071, and with the alliance of the royal houses of Scotland and Wessex the northern kingdom begins to emerge from its barbaric isolation, and to fill a permanent place in the political scheme of English statesmen.

To William the marriage was no matter of congratulation. It meant that the Scottish court would become definitely interested in the restoration of the old English dynasty; so long as such an event were possible, it was likely to make Scotland both a refuge and a recruiting ground for any 323political exile who might choose to attempt his return by force and arms. To minimise these evils, and to avenge the harrying of 1070, the Conqueror in the summer of 1072 set out for Scotland in person. The expedition was planned on a great scale; the fyrd was called out, and the naval force which was at William’s command co-operated with the native host. Malcolm seems to have felt himself unequal to meeting a force of this size in the open field; he allowed William to pass through Lothian and to cross the Forth without any serious obstruction, and the two kings met at Abernethy on the Tay. There Malcolm renewed his homage to William, made peace, and gave hostages for its observance, among them Donald, his son by his first wife, Ingibiorg. The expedition could not have been intended to accomplish more than this, and William at once turned southwards, retracing his steps along the great east coast road.[247]

Nothing appears to have been done at this time to improve the defences of the northern border. Carlisle remained in Scotch hands, and the site of the future Newcastle on the Tyne is only mentioned in the record of this march through the fact of the river being flooded at the moment when the army sought to cross it, thereby causing an inconvenient delay. The importance of the Teesdale gap had been sufficiently proved by the events of 1070, but no attempt was made to 324guard the course of the river in any special manner. On the other hand we should do well not to ignore the possibility that the first creation of the earldom of Richmond immediately to the south of the Tees may not have been unconnected with the advisability of keeping a permanent military force in this quarter. The earldom in question had been conferred upon Brian of Penthievre in or before 1068, and had passed from him to his brother Alan by the date of the events with which we are dealing.[248] So far as we know King William never created an earldom save for purposes of border defence, and the geographical facts which we have just noted make it distinctly improbable that Richmond was an exception to this rule.

Two important changes in the government of Northumbria would seem to have been carried out at this time. The first was the installation of Walcher of Lorraine as bishop of Durham, and his establishment in a castle especially built for him, so that he might be secure against any spasmodic rising on the part of the men of his 325great diocese. The second event was the deposition of Earl Gospatric. He was held guilty, we are told, of complicity in the murder of Robert de Comines, and the Danish storm of York in 1069, although his offences in both these matters had been committed previous to his reconciliation with William in 1070. Whatever may have been the true cause of his downfall, it was followed immediately by the restoration of the house of Siward to its former position in the north, for the earldom of Northumbria was now given to Waltheof of Huntingdon, Siward’s son, and remained in his hands until the catastrophe which overtook him three years later. Gospatric in the meantime betook himself to his cousin’s court and received from him a large estate in Lothian, centring round the town of Dunbar, until he might be restored to King William’s favour. With this act his political importance ceases; Domesday proves that the whole or part of his Yorkshire estates had been restored to him by the time of the taking of the Survey, but he never recovered his former rank and influence.

It has been conjectured with much probability that one of the conditions of the peace of Abernethy was the expulsion of Edgar the Etheling from Scotland.[249] Shortly after this time he appears as beginning a series of journeys, which before long brought him once more into England as the honoured guest of King William. His first visit 326was paid to Flanders, where he would be sure of a kindly reception from Robert the Frisian, by this time William’s mortal enemy. After a stay of uncertain length in Flanders he returned to Scotland, where he landed early in July 1074, and was hospitably entertained by his sister and her husband. Before long, however, he received an invitation from King Philip of France, offering to put him in possession of the castle of Montreuil, which he might use as a base from which to attack his enemies.[250] The offer shows considerable strategical sense in the young king of France. Montreuil was the first piece of territory which the Capetian house had gained on the Channel coast, but it was separated by the possessions of the house of Vermandois from the body of the royal demesne, and it lay between the counties of Ponthieu and Boulogne. Once established in Montreuil Edgar could have received constant support from Robert the Frisian; and if the counts of Ponthieu or Boulogne wished to revolt from the Norman connection Edgar’s territory would have made it possible to form a compact and powerful league against the most vulnerable part of the Norman frontier.

Edgar complied with King Philip’s request, and set out by sea to take possession of his castle; the good-will of his Scottish protectors being expressed in a multitude of costly gifts. Unfortunately for the success of his enterprise he was 327speedily driven on to the English coast by a storm and some of his men were taken prisoner, but he succeeded in reaching Scotland again, although in very miserable condition. Curiously enough this slight check to his plans seems to have caused him to abandon outright the idea of occupying Montreuil, and we are told that his brother-in-law advised him to make terms with King William. The Conqueror was at the time in Normandy, but he gave a ready hearing to the overtures from Edgar and directed that an escort should be sent to accompany him through England and across the Channel. Of the meeting between the king and the etheling in Normandy we possess no details, but the English writers were struck with the honours which the Conqueror showed to his former rival,[251] and Domesday reveals the latter in peaceable possessionpossession of upwards of a thousand acres of land in the north-east of Hertfordshire. For the rest of William’s reign Edgar remained a political cipher.

We have now reached the central event of William’s rule in England, the revolt of the earls in 1075. The rising in question is sufficiently characterised by the name which is generally assigned to it; it was a movement headed by two of the seven earls who held office in England, incited by the motives proper to men of their rank, and finding little support outside the body of their personal dependants. It had no popular 328or provincial feeling behind it; it cannot even be described as a purely Norman revolt, for the mass of the English baronage held true to King William, and its most striking result was the execution of the last English earl, for complicity in the designs of his Norman confederates.

On the death of William Fitz Osbern in 1071 his earldom of Hereford had passed to his son, a stupid and vicious young man, in every way a degenerate successor to the tried and faithful friend of the Conqueror. From the moment of his succession to his earldom Roger seems to have kept himself in sullen isolation in his palatinate across the Severn; his name has not yet been found among the visitors to William’s court who witnessed the charters which the king granted during these years, and we should know nothing about the man or his character if it were not for the preservation of three letters addressed to him by his father’s old friend Archbishop Lanfranc. At the time when these letters were written, William was in Normandy, and Lanfranc had been left in a sort of unofficial regency, in which position he had clearly been rendered uneasy by rumours of Roger’s growing disaffection. Lanfranc, in his correspondence, was tactfully indefinite on the latter point, but he was very outspoken in regard to Roger’s personal acts of oppression and injustice. By the example of William Fitz Osbern, “whom,” says Lanfranc, “I loved more than anyone else in the world,” 329the archbishop pleaded with his friend’s son to amend his conduct, and promised to see him and give him counsel on whatever occasion he might choose. But Roger remained obdurate, and in the last letter of the three which we possess Lanfranc declares Roger excommunicate until he has compensated those whom he has injured, and has made his peace with the king for his arbitrary acts in his earldom.

The position of Waltheof at this time has already been described. His Bernician earldom was less important on this occasion than were the group of shires in the eastern midlands over which he also possessed comital rights. The four counties of Northampton, Bedford, Huntingdon, and Cambridge, together with Waltheof’s extensive estates in Leicestershire and Warwickshire, went far towards connecting the palatinate of Hereford with the distant earldom of East Anglia, the most dangerous quarter of the present rebellion.

The earl of East Anglia, Ralf of Wader, might, like Waltheof, claim to be considered an Englishman; for, although his mother was a Breton and his father also bore the Norman name of Ralf, the latter was an Englishman of Norfolk birth, and had been earl of East Anglia under Edward the Confessor and during the earliest years of the Conqueror. Ralf the younger, despite his succession to his father’s earldom, is identified with his mother’s land of Brittany, where he held the 330estates of Wader and Montfort, rather than with England.[252] Like Roger of Hereford, and judging from the same evidence, Earl Ralf would seem to have been a consistent absentee from William’s court, and his one appearance in the history of the latter’s reign, previous to his own revolt in 1075, took place in 1069, when he beat off the Danes from the estuary of the Yare.

The immediate cause of the present outbreak was the Conqueror’s objection to a marriage which had been projected between Earl Ralf and Emma, daughter of William Fitz Osbern and sister of Roger of Hereford. The reasons for the Conqueror’s action are intelligible enough; nothing could be further from his interest than the creation of a series of marriage ties among the greater vassals of his crown, especially when the parties to be connected in this way held the wide military and territorial powers which at this early date were inherent in the dignity of an earl. There is no reason to suppose that Earl Ralf’s loyalty had been suspected at any earlier time or that there was anything deeper than the royal prohibition of his marriage which now drove him into revolt. Without the king’s consent, the marriage was celebrated and the wedding feast held at Exning in Cambridgeshire, a vill within Waltheof’s earldom. Earls Roger and Ralf had already made preparations for their 331rising, their friends had been acquainted with their intention, and their castles were prepared to stand a siege; and at Exning a determined attempt was made to seduce Waltheof from his temporary fidelity to King William. His accession to their cause might very possibly bring with it some measure of English support, he had a great popular reputation as a warrior, and the plans and motives of the conspirators were unfolded to him at the wedding feast with startling frankness. The occasion was hardly such as to produce sobriety of counsel, and in the one extended narrative which we possess of the original plot, the terms of the offer now made to Waltheof were involved in a long harangue, in which the deposition of the Conqueror was declared to be a matter pleasing to God and man, and every event in William’s life which could be turned to his discredit was brought forward, heightened according to the taste of the conspirators or the literary skill of our informant. More important than the grotesque crimes attributed to the Conqueror are the plans formed by the earls for the event of his expulsion. Their object, we are told, was to restore England to the condition in which it had existed in the days of Edward the Confessor. With this object, one of the three chief plotters was to be king, the other two earls; Waltheof in particular was to receive a third part of England. William was declared to be fully occupied beyond the sea, his Normans in England were assumed 332to be discontented with the reward they had received for their services, and it was suggested that the native English might be willing to rise once more if a chance of revenge were offered them. Waltheof was assured that the chances of a successful rising could never be higher than at the moment in question.[253]

The narrative of Ordericus Vitalis, which we have hitherto been following, makes Waltheof indignantly refuse to be a party to any scheme of the kind. By the examples of Ahitophel and Judas Iscariot he demonstrated the sinister fate that was the portion of a traitor, and declared that he would never violate the confidence that King William had placed in him. On his refusal to join the plot, he was compelled to take a terrible oath not to betray the scheme and the rising was accomplished without his assistance; but after its suppression the tale makes Waltheof accused of treason by Judith his wife before the king, and describes his behaviour in prison and the manner of his end with great wealth of detail and a not improbable approximation to the facts of the case. It seems fairly certain that Waltheof took no effective part in the military operations which followed the bridal of Exning, and we may consider the difficult question connected with his trial and execution apart from the details of the war.

The plan of campaign followed by both sides 333was extremely simple. Neither the earldom of East Anglia or of Hereford acting by itself could obtain any permanent success against the loyal portions of the country; the object of the rebel leaders was to join their forces, and the object of King William’s lieutenants was to prevent the combination. The line of the Severn was guarded against Earl Roger of Hereford by the local magnates of Worcestershire, Wulfstan the bishop, and Urse d’Abetot the sheriff of the shire, Agelwig, abbot of Evesham, and Walter de Lacy, at the head of a force composed of the local fyrd in conjunction with the knightly tenants from their own estates.[254]

The Herefordshire revolt had soon run its course; Earl Roger never got across the Severn and within a short time had been taken prisoner, but the earl of East Anglia was a person of greater ability. Before engaging in the rebellion the earls had sought for external help; application had been made to the King of Denmark for a fleet, and reinforcements had been drawn from Brittany, recruited in great part, no doubt, from the Breton estates of Ralf de Wader. From the latter’s head-quarters at Norwich a highroad of Roman origin stretched invitingly across the Norfolk plain towards the royal castle of Cambridge, and Earl Ralf moved westward in the hope of effecting a junction with Roger of Hereford; but at an unknown place in the neighbourhood 334of this line, designated by Ordericus Vitalis as “Fagadun,” the rebel army was broken and scattered, and from a letter which Lanfranc wrote to the king immediately after this event, the archbishop was evidently in expectation of a speedy suppression of the whole rising. That this hope was frustrated was due to the heroism of Earl Ralf’s bride, who undertook the defence of Norwich castle in person, while her lord went off to Denmark, and held out for three months against all that the Norman commanders could do. At last she was compelled to surrender upon conditions. The Breton tenants of Earl Ralf in England were required to abandon their lands and to withdraw to Brittany within forty days; the mercenaries of the same race were allowed a month to get away from the country. Emma herself, to whom belonged all the honours of the war, went to Brittany, where she met her husband, and Norwich castle was once more occupied in the king’s name.

Earl Ralf’s journey to Denmark had not been fruitless, for a fleet of two hundred Danish ships appeared in the Humber shortly after the fall of Norwich, under the command of Cnut, son of King Swegn Estrithson, and a certain earl called Hakon.[255] Their coming reopened an endless possibility of further trouble; the Conqueror, through Archbishop Lanfranc, enjoined Bishop Walcher of Durham to look well to the defences 335of his castle.[256] But the first object of the ordinary Danish commander of those times was always plunder, and Cnut after successfully evading the royal troops contented himself with the sack of York cathedral, and quickly sailed away to Flanders. In the very year of this expedition (1075), Swegn Estrithson died, and Harold, his eldest son, who succeeded him, kept peace towards England throughout his reign. In the autumn of 1075 William had returned to England, and at Christmas he proceeded to deal with the persons and property of the revolted earls. Waltheof and Roger were in his power; Ralf was safe beyond the sea, but his English lands remained for confiscation, and such of his Breton associates as were in the king’s hands were punished according to the fashion of the times. Earl Roger was sent to prison, but his captivity at first was not over severe, and had it not been for his contumelious conduct towards the king he might have obtained his release in due course. Unfortunately for himself, he mortally offended William by throwing into the fire a rich present of silks and furs which the king sent to him one Easter, and perpetual captivity was the return for the insult. The relative leniency of the Conqueror’s treatment of Roger contrasts very strikingly with his attitude to the third earl implicated in the revolt, and no incident in King William’s career has won more reprobation from medieval and modern 336historians than the sentence which he allowed to be passed on Earl Waltheof.

We have already sketched in outline the narrative of Waltheof’s action as given by Ordericus Vitalis, and it will be well now to consider briefly the independent story told by the native English chronicles.[257] On all accounts it is certain that Waltheof had been implicated in the treason proposed at Exning, and it is no less clear, though the fact is suppressed by Orderic, that he had speedily repented and under the advice of Lanfranc had revealed the whole scheme to King William in Normandy.[258] The part played by Lanfranc is explicable, not only by the species of regency he held in the kingdom at the time, but also by his position as metropolitan of the English church, and his reputation as a famous doctor of the canon law. No man was better qualified to give a sound opinion as to the circumstances under which an indiscreet oath might be broken without the guilt of perjury; and the penances which he imposed on Waltheof for his intended breach of the engagement which he had taken at Exning seem to have been accepted by all parties as a satisfactory solution of the matter. On his part, William bided his time; he appears to have accepted the gifts which Waltheof offered as the price of his peace, and he contented himself 337with keeping the earl under his own supervision until his return to England. Not till then was Waltheof placed under actual arrest, and it has been conjectured that the reason for this action was the fear that he might make his escape to the Danes in the Humber.[259] At the midwinter council of 1075 he was brought to trial, whether or not upon information laid against him by his wife, the countess Judith, and although no definite sentence was passed against him at this time he was sent into closer imprisonment at Winchester.

For the first five months of 1076 Waltheof’s cause remained undecided. It is clear that there was considerable uncertainty in high quarters as to what should be done with him. Lanfranc interceded on his behalf, apparently going so far as to declare him innocent of all complicity in the revolt. We are told nothing of the Conqueror’s own sentiments in the matter, but the strange delay in the promulgation of definite sentence suggests that throughout these months he had been halting between two opinions. At last the sterner view prevailed, and under the influence of Waltheof’s Norman rivals at the royal court, according to Ordericus Vitalis, the king gave orders for the execution of the last English earl.

Early on the morning of the 31st of May, Waltheof was taken from his prison in Winchester to die on the hill of St. Giles outside the city. Accustomed hitherto to the active life of his 338northern ancestors, the monotonymonotony of his imprisonment would seem to have destroyed his courage, and the fatal morning found him in bitter agony of soul. The executioners, who feared a rescue, and were anxious to get through with the work, had little patience with his prayers and weeping, and bade him rise that they might carry out their orders. Waltheof begged that he might be allowed to say a pater noster for himself and them, and they granted his request, but at the clause “et ne nos inducas in tentationem” his voice failed him, and he burst into a storm of tears. Before he could recover his strength, his head had been struck from him at a single blow, but the monks of Crowland abbey, where his body lay in after years, told their Norman visitor Ordericus Vitalis that the severed head was heard duly to finish the prayer with “sed libera nos a malo, Amen.”

The case of Earl Waltheof involves two separate questions which it is well to keep distinct in estimating the justice of King William’s conduct in the matter. The first is how far Waltheof had really implicated himself in the designs of the earls of East Anglia and Hereford; the second is what, on the assumption of his serious guilt, would have been the lawful punishment for it. It does not seem likely that the first question will ever be finally answered, for by a singular chance none of our authorities are quite disinterested when they relate the circumstances of Waltheof’s 339fall. The Anglo-Saxon chronicler and Florence of Worcester, compatriots of the dead earl, lie under some antecedent suspicion of minimising the extent to which he had compromised himself; and Ordericus Vitalis, to whom we should naturally turn for a statement of the Norman side of the case, based his accountaccount of Waltheof upon information received from the monks of Crowland at a time when the earl was, in popular sentiment, rapidly becoming transformed into a national martyr. Orderic’s narrative, written under such influences, has just as much historical value as any professed piece of martyrology; that is, it probably presents the authentic tradition of the details of its hero’s death, but it is not concerned to pay a scrupulous regard to facts which might be inconvenient for his reputation. And so King William for once has no apologist; but sixty years after the event it was recognised by an impartial writer like William of Malmesbury[260] that the Norman story about Waltheof was very different from that which the English put forward. With such untrustworthy authorities as our only guides, we should scarcely attempt to settle a matter which in the days of King Stephen was already a burning question, but our hesitancy should make us pause before we accuse King William of judicial murder.

To the second of the problems arising out of the case—the sentence which followed Waltheof’s 340condemnation—it is possible to find a more satisfactory answer. Nothing is more probable than that the Conqueror, in sending Roger of Hereford into prison and beheading Waltheof, was simply applying to criminals of high rank the great principle that men of Norman or of English race should be judged respectively according to Norman or English law.[261] Earl Roger as a Norman, according to a practice on which we have already had occasion to remark, was condemned to imprisonment, but English law regarded treason as a capital offence, and Waltheof suffered the strict legal penalty of his crime. Indeed, Waltheof himself, in Orderic’s version of his reply to the conspirators at Exning, is made to declare that the English law condemned a traitor to lose his head, and it is probable that he was better informed on this point than have been some of the later historians who have undertaken his defence. During the next century, members of the Norman baronage established in England who had raised an unsuccessful revolt uniformly received sentence according to the rule which applied to men of their race; and the execution of a traitor against the king will scarcely occur between 1100 and 1200, and but rarely in the course of the thirteenth century. But Waltheof had no privilege of the kind, and, stern as was his sentence, he might not complain that formal justice had been denied him.

341The revolt of 1075 produced a sequel in a small continental war. Earl Ralf, as we have seen, had fled to his estates in Brittany, and his appearance coincided in point of time with the outbreak of a general revolt among the Breton baronage. Count Hoel, who possessed in his own right five-sixths of Brittany, was the first of his line to exercise effective rule over the whole peninsula, and the fact was little to the liking of his greater subjects. The malcontents found a leader in Geoffrey “Grenonat,” count of Rennes, an illegitimate son of Alan III.; and the dispossessed earl of East Anglia brought the resources of his barony of Wader to their side. Ralf and Geoffrey seized the castle of Dol; and the rising assumed such serious proportions that Hoel sent to England, and requested King William’s assistance. William, ever desirous of asserting Norman influence in Brittany, took the present opportunity, and in 1076 he crossed the Channel with a force which to the chroniclers of Worcester and Peterborough represented an English fyrd, and laid siege to Dol. The result was a serious loss of prestige, for the garrison had answered Hoel’s application to William by making a counter-appeal to Philip of France, and held out valiantly in the expectation of relief. Philip took the field with a large army, advanced to Dol, and took a measure of revenge for his father’s discomfitures at Mortemer and Varaville, by compelling William to beat a hasty retreat with the loss of his baggage and 342stores. William engaged no further in the war which dragged on for three years longer, but ended in 1079 with the final success of Hoel.[262]

In the meantime, certain important changes had taken place in the administrative geography of England. The earldoms of Hereford and East Anglia, vacant through the treason of Earls Roger and Ralf, were allowed to fall into abeyance. Waltheof’s earldom of Northampton likewise became extinct, although his widow, the countess Judith, was possessed in 1086 of large estates scattered over the shires which had lain within her husband’s government. There was no particular reason why Northamptonshire should possess an earl, but it was still abundantly necessary that William should be represented by a permanent lieutenant on the Scotch border. An earl for Bernicia was now found in the person of Walcher of Lorraine, whose appointment anticipated by more than sixty years the beginning of the long series of bishops of Durham, whose secular powers within their diocese produced the “county palatine” which lasted until 1836.[263] The experiment 343made in Walcher’s appointment was destined to end in tragic failure, but for four years Northumbrian affairs relapse into unwonted obscurity, and the Conqueror was never again called upon to lead an army into the north.

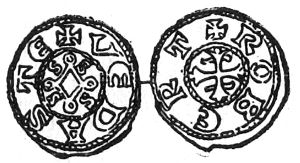

Denier of Robert le Frison

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content