Search london history from Roman times to modern day

A historical site about early London coffee houses and taverns and will also link to my current pub history site and also the London street directory

An account of the Ancient Mourning Bush Tavern, Aldersgate, &c.

Ancient Mourning Bush Tavern, Aldersgate - in 1746

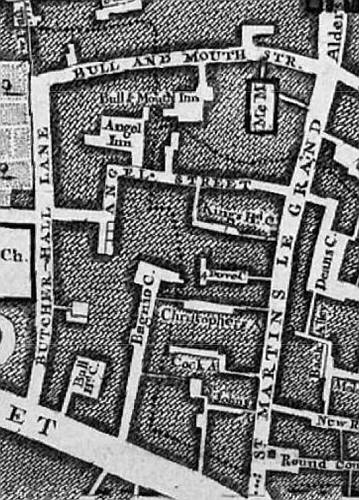

Rocques map

Research has failed to produce much respecting the old Mourning Bush Tavern, by

Aldersgate, further than to satisfy us that it was highly celebrated in its day,

and must from its remains have been one of the largest and most ancient taverns

in London. The history of such a place, had it been preserved, would no doubt

have abounded with amusing anecdote. No account, however, has transpired that we

have heard of, and, independently of the interest arising from its age, and some

other circumstances which will be hereafter noticed, we only find a single

historical, fact concerning it,— the modern version of which is thus given, in a

dissertation on signs, in the Gentleman's Magazine for 1818;— the conclusion

expresses a wish, which the reader will see is at length adopted.

"An innkeeper in Aldersgate Street, London, when Charles I. was beheaded, had

the carved representation of a bush at his house painted black, and the tavern

was long afterwards known by the name of the Mourning Bush, In Aldersgate; I

wish that the sign was revived, as a memorial of a man, who had, the courage so

conspicuously to display his loyalty at such a time to his unfortunate

sovereign, 'more sinned against than sinning.'"

The inaccuracy of the writer here in designating the landlord of the Mourning

Bush Tavern, an innkeeper, instead of a vintner, makes nothing against the truth

of the story, which is told also in works of the civil war period, and is

corroborated elsewhere; like the Bush, the principal tavern at Bristol, and the

Ivy-bush, the head inn at Caermarthen, the sign mentioned, no doubt originated

in the practice of hanging a bush at the door of vintner's houses, whence the

proverb, "good wine needs no bush."

Ivy was chosen for this purpose with classical propriety, that plant being

sacred to Bacchus, whose thyrsus it entwined, and it is accordingly often

alluded to by old writers :—

" Now a days the good wyne needeth none ivye garland."

Gascoigne's Glass Of Gov'.

"'Tis like the ivy bush unto a tavern."

Rival Friends.

Hearne copied the following anecdote of a similar nature from a paper in the

hand-writing of Dr. Richard Rawlinson:— " Of Daniel Rawlinson who kept the Mitre

Tavern in Fenchurch Street, and of whose being suspected in the Rump time I have

heard much. The Whigs tell this, that upon the king's murder, he hung his sign

in mourning: he certainly judged right. The honour of the mitre was much

eclipsed through the loss of so good a parent to the church of England.

"These rogues say, this endeared him so much to the churchmen, that he soon

throve amain, and got a good estate."

Tavern Anecdotes, 1825.

"Green ivy bushes at the vintner's door."

Summers' Last Will And Testament.

"The good wine I produce needs no ivy bush."

Summary On Du Bartus.— To the Reader.

Rosalind's " Good wine needs no bush," in the Epilogue to As you Like It, also

refers to this same custom, though the species of bush, ivy, is not named.

* The subsequent passage seems to prove, that anciently tavern keepers kept both

a bush and a sign: a host is speaking.

"I rather will take down my bush and sign

Than live by means of riotous expence."

Good Newes And Bad Newes, by S. R. 4to. Lond. 1622.

In " England's Parnassns," 4to. Lond. 1600, the first line of the Address to the

Reader runs thus:—"I hang no ivie out to sell my wine;" and in "Brathwaite's

Strappado for the Divell," 8vo. Lond. 1615, there is a dedication to Bacchus, "

sole sovereign of the ivybush, prime founder of red lattices, &c."

And in " Vaughan's Golden Grove," 8vo. Lond. 1608, is the following passage:—"

Like as an ivy-bush put forth at a vintrie is not the cause of the wine, but a

signe that wine is to be sold there, so likewise if we see smoke appearing in a

chimney, wee know that fire is there: albeit, the smoke is not the cause of the

fire." And the following from Harris's Drunkard's Cup:— " Nay, if the house be

not worth an ivy-bush, let him have his tooles about him, nutmegs, rosemary,

tobacco, with other the appurtenances, and he knowes how of puddle-ale to make a

cup of English wine."

And as late as 1678, as we find by Poor Robin's Perambulation from Saffron

Walden to London," printed that year, ale-houses where they also sold wine,

denoted the same by hanging out a bush.

"Some ale-houses upon the road I saw,

And some with bushes, showing they wine did drawe."

Mr. Fosbroke (Dictionary of Antiquities,) mentions the Bush as the chief sign of

taverns in the middle ages, and tells us it continued until at length it was

superseded by "a thing intended to resemble one, containing three or four tiers

of hoops fastened one above another, with vine leaves and grapes richly carved

and gilt." He adds, "The owner of the Mourning Bush, Aldersgate, was so affected

at the decollation of Charles I. that he painted his bush black."

That the Mourning Bush, or rather the Bush Tavern, existed ages before the

anecdote alluded to, there are Various evidences besides the antiquity Of its

foundations, though We have no means of ascertaining its precise age. The sign

alone, would rank it amongst the earliest London taverns, as the affixing the

ivy-bush at the door, we see was a practice of remote date, and when used as the

only sign of the house it was attached to, it marked in it a still higher date.

Considering then, that the alteration by its loyal owner alone carries us back

nearly two centuries, and that it was at this period no doubt, an Old house, it

will not at all be assuming too much to suppose the bush might have been coeval

with the most nourishing times of St. Martin's-le-grand College. This conjecture

is strengthened by reverting to the then state of the neighbourhood, and the

utility such a house must have been of, so situated. When Aldersgate Street was

a mere country road from the north parts of the kingdom, bounded on its west

side the whole distance between Long Lane and Little Britain, by Bartholomew

priory wall, and the numerous alder trees which are said to have given this

thoroughfare its name; and, on its opposite side, equally dreary, was only the

great burial pound of the Jews, with scarcely a cheerful dwelling; a house for

refreshment immediately the traveller entered the city gate might be reasonably

expected; and where could such a house be so appropriately situated, as between

St. Anne's Church and the gate? All the space on the other side was occupied

with Northumberland house and gardens— the town mansion of the gallant Percies;

that is to say, when they were in town: for the business of these great peers,

was chiefly in the camp, as Pennant observes, "which they seldom quitted for

London, but to brave the sovereign or the favorite."

What public houses there were within St. Martin's Liberty, being " sanctuary,"

would be closed at nine o'clock at night, with the closing of the college gates.

We repeat, therefore, where could the traveller on entering town from the great

north road, be likely to be more commodiously and readily suited— as he may

still— than at the Bush, which besides its convenient situation, pleasantly

overlooking the " Dean's Garden," must have enjoyed an atmosphere as unconfined

and salubrious, as it does now from the open and magnificent area of the New

Post Office?

A few observations respecting our ancient taverns will, perhaps, be not

inappropriately introduced here, in the paucity of information which exists

relative to the Mourning Bush.

Though the " win-hous," or tavern, is enumerated amongst the houses of

entertainment in the Saxon times, and no doubt existed here much earlier, there

is reason to think, that down to a comparatively late period it was far from

common, as was the case also with public inns. Monasteries were the usual places

at these remote dates which afforded relief to the traveller. Lord Berkeley's

farm houses, in the part of the country where they stood, were used instead, in

the time of Edward I. and some who could not be otherwise accommodated, not only

enquired out hospitable persons, but even applied for entertainment at the

king's palaces. Knights lodged in barns, and John Rous, the monk, who mentions a

celebrated inn on the Warwick road, was yet forced himself to go another way for

want of one.

Their utility had become apparent before Edward II. for a statute of the 12th of

that prince, in order that the public might not be injured, forbids officers in

towns and boroughs— whose duty it was to keep assizes of wine and victuals, to

merchandize themselves for either, on pain of forfeiture to the king.

The dealers in wine at the above period, and long before, were of two

descriptions; the vinterarij and the tavernarij, that is, the vintners, who were

the merchants that imported wine from France and other places, and the taverners

who kept taverns for them, and sold it out by retail to such as came thither to

drink, or fetched it to their own houses. Of both these sellers of wine it was a

complaint as long ago as the reign of Edward III. that they mixed and corrupted

their wine, and sold that so mixed at the same price with the good, which caused

that king in the second year of his reign, to send his letters to the mayor and

sheriffs to see this abuse corrected; which was, as the expression in the said

letter is, to the scandal of the city, and the danger of the lives of the

citizens; and that they should cause it to be proclaimed, that no wine should be

sold but pure and good; and that it might be known immediately to be so, it was

ordered to be proclaimed, " That all and singular persons drinking wine in

taverns, or otherwise buying wine from them, may look as they will, whether the

wines so sold, as aforesaid in taverns, be drawn out of the hogshead, or taken

from elsewhere."

The act of parliament of the 4th of the same prince, enforces in more distinct

terms the prohibition in the proclamation as to taverners, and prescribes

various regulations for the conducting of their trade. It states:—

"Because there be more taverns in the realm than were wont to be, selling as

well corrupt wine as wholesome, and have sold the gallon at such price as they

themselves would, because there was no punishment ordained for them, as hath

been to them who sold bread and ale, to the great hurt of the people; it should

be accorded, that a cry should be made, that none be so hardy to sell wines but

at a reasonable price, regarding the price by the price at the parts from whence

the wines came; and the expences, as in carriage of the same from the said parts

to the places where they be sold; and that assay should be made of such wines

two times in every year, once at Easter, and another time at Michaelmas, and

more often if need be, by the lords of the towns, and their bailiffs, and also

by the mayor and bailiffs of the same towns; and all the wines that shall be

found corrupt, (putrified,) shall be shadde and cast out, and the vessels

broken; and the chancellor and treasurer, justices of the one bench, and the

other, and justices of assize, shall have power to enquire upon the mayor,

bailiffs, and ministers of towns, if they did not according to this statute; and

besides that, to punish as reason should require." And the more effectually to

hinder the importation of bad wines, as well as the adulteration of the good by

retailers, the same king Edward III. afterwards in the 35th of his reign, in his

letters patent for regulating the guild or company of vintners, prohibits any to

deal in Gascoigne wines '* but such alone as were enfranchised in the craft of

vintrie:" and we may here observe, in contradiction to some old writers, that

the trade are nowhere in the said letters patent called "wine-tonners," (which

is said to be the original of vintners,) but " vinteners," and " merchants

vinteners," and " merchants of vintrie."

Chaucer makes his idle city apprentice a great tavern haunter soon after this

period:—

"A prentis whilom dwelt in onr citee,—

At ev'ry bridale wold he sing and hoppe;

He loved bet' the Tavern than the shoppe,

For whan ther any riding was in Chepe,

Out of the shoppe thider wold he lepe;

And til that he had all the sight ysein

And dancid wel, he wold not com agen."

As to the retail of wines, it was ordained by statute of Richard II. " That of

wines of Gascoine, of 0sey, and of Spain, brought within the realm by

Englishmen, the gallon of the best wine should not be sold above six-pence, and

within, according to the value; and as to the Rhenish wines brought within the

Same realm," (because the vessels and the gallons of the same did not contain

any certain measure,) " it was accorded and assented, that the gallon of the

best should also not be above six-pence," and they were to be compelled to sell

them at these prices. "And it not being the king's mind to restrain taverners,

and other sellers of wines carrying the same into the country by carts, or in

any other manner, they were allowed to enhance the price accordingly, via.— a

halfpenny a gallon was to be allowed for the carriage for fifty miles of every

gallon, and so in proportion.

Agreeably to these ordinances, the ancient assize of a taverner in the city of

London states, "That he shall be non excessif taker more of the rede wyne of

every galon, but 2nd wynnyng, (profit,) and of al oder swete wynnys, but 4d.

wynnyng of the galon. And he shall set no maner of wyne a sale tyl he has sent

aftyr the officers of the towne, that is to say, the mayor or bailiff, or the

deputies assigned, for to tast it, and se that it be good and abul wyne; and his

vessels to be gaugid, and so markyd upon the heddys; and there to be sworn afore

the officers what it cost; and aftyr that, he for to sell; also he shall sell no

wine, but by measure assized and selid."

If the taverner did contrary to any of these regulations, he was to be amerced;

and if he sold "any fectife (defective) wyne, his tavern door should be selid

in," and he was to be further fined and judged according to the statute.

Not only did the importers of wines in those early times become immensely rich,

and fill the highest civic offices, but even the retailers or taverners

themselves frequently became sheriffs, and sometimes mayors— such were

Brengeveye de Oxenford, Burgoin, Parys, Roffam, &c. all sheriffs; and Richard

Bretayne, who was mayor 1 Edw. I.

The curious old ballad of London Lockpenny, written in the reign of Henry V. by

Lydgate, a monk of Bury, confirms the statement of prices of Richard the IId's

reign. He represents a countryman come up to town to see the " sights" of

London. In Eastcheap, the cooks cried hot ribs of beef roasted, pyes well baked,

and other victuals; there was clattering of pots, harp, pipe, and sawtre,

yea-by-cock, nay-by-cock, for greater oaths were spared; some sang of Jenkin and

Julian, &c. lie from hence comes to Cornhill, when the wine drawer of the Pope's

Head tavern, standing without the door in the high street, for it was then the

custom for these drawers to way-lay passengers like the barkers in Monmouth

Street, takes the same man by the hand, and says—" Sir, will you drink a pint of

wine? Whereunto the countryman answers, " A penny spend I may," and so drank his

wine. "For bread nothing did he pay"—for that was given in."*

The ballad itself states the matter different from the above account of Stowe,

making the Taverner, and not the Drawer, invite the countryman; and the latter,

instead of getting bread for nothing, complains of having to go away hungry:—

"The Taverner took me by the sleeve,

'Sir,' saith he,' will you our wine assay?'

I answered—that much can't me greve.

So that it appears, there was no eating at taverns beyond a crust to relish the

wine, which was given in; and if you wished to dine before you drank, you must

first go to the cook; and after to the vintner, or as Stowe has it—" Of old

time, when friends did meet, and were disposed to be merry, they went not to

dine and sup in taverns, for they dressed no meats to be sold, but to the

cook's, where they called for what meat pleased them, which they always found

ready dressed, and at a reasonable price."

And the historian afterwards confirms this by the following anecdote :—In the

year 1410, the 11th of Henry IV. upon the even of St. John the Baptist, the

king's sons, Thomas and John, being in Eastcheap at supper, or rather breakfast;

for it was after the watch was broken up, betwixt two or three of the clock

after midnight, a great debate happened between their men and others of the

court, which lasted one hour, even until the mayor and sheriffs, with other

citizens appeased the same; for which afterwards the said mayor, aldermen, and

sheriffs, were sent for to answer before the king, his sons and divers lords

being highly moved against the city. At which time William Gascoigne, chief

justice, required the mayor and aldermen, for the citizens, to put them in the

king's grace. Whereupon they answered, that they had not offended, but,

according to the law, had done their best in stopping debate, and maintaining of

the peace; upon which answer the king remitted all his ire, and dismissed them."

A penny can do no more than it may:

I drank a pynt, and for it did pay;

Yet sore a hung'red from thence I yede,

And wanting of money I could hot spede."

The above statements make Strype,— Survey of London, 1720, assert,

(notwithstanding the high treason of contradicting Shakespeare,) that there was

at this period "no tavern in Eastcheap. The bard, however, living within the

traditional memory of the thing, would most probably not be mistaken: It is also

said by the commentators; and we believe so far must be admitted, that the

furnishing the Boar's Head with sack in the reign of Henry IV. is an

anachronism; for the vintners kept neither sacks, muscadels, malmsies, bastards,

alicants, nor any other wines but white and claret, until 1543, and then was old

Parr, as himself relates, 60 years of age. All the other sweet wines before that

time were sold at the apothecary's shops, for no other use, but for medicine.

Taking it as the picture of a tavern a century later, we see the alterations

which had taken place:—

The single drawer or taverner of Lydgate's day is now changed to a troop of

waiters, of whom the prince jokes he can himself name half a dozen; besides

alluding to "the under skinker" or tapster. Eating was no longer confined to the

cook's row, for we find by the enumeration in Falstaff's bill— "a capon 2s. 2d.

sack, 2 gallons, 5s. 8d. anchovies and sack after supper 2s. 6d. bread, one

half-penny." And there were evidently different rooms for the guests, partly

furnished with modern conveniences, as Francis bids a brother waiter " Look down

into the Pomgranite." * For which purpose it seems they had then windows or loop

holes, affording a view from the upper to the lower apartments.

* A successor of Francis was a waiter at the Boar's Head in modern times, and

had formerly a tablet with this inscription in St. Michael's Crooked Lane

church-yard, just at the back of the tavern;

Many other particulars may be observed, tallying with the descriptions of

taverns in the reigns of Elizabeth and James; such are the introduction of Doll

Tearsheet, and the prince's simile respecting her, of the sun's being " a hot

wench dressed in flamecoloured taffita"—the mention of " Sneak's Noise," or

itinerant band of musicians, &c. "You shall there see" (viz. at the low taverns)

"a paire of harlots in taffita gowns, like painted posts', garnishing out those

dores, being better to the house than a double signe."

"Neither were they any of those with terrible "Noyses" and threadbare cloakes,

that live by red lattises and ivy-bushes, having authority to thrust into any

man's roome; only speaking but this, " will you have any musique?"

"To the memory of Robert Preston, late drawer at the Boar's Head tavern in Great

Eastcheap, who departed this life March 10, A.d. 1730, aged twenty-seven years."

Also several lines of poetry quoted in Malcolm's Londinum Redivivum, setting

forth Bob's sundry virtues, particularly his honesty and sobriety; in that—

"Tho' nnrs'd among full hogsheads he defied

The charms of wine, as well as other's pride."

He possessed also the singular virtue of drawing good wine, and of taking care

to "fill his pots," as appears by the concluding lines of admonition.—

"Ye that on Bacchus hare a like dependance,

Pray copy Bob in measure add attendance.''

Red lettuce.—The chequers at this time a common sign of a public house, as

indeed it is to this day, is originally thought to have been intended for the

kind of draught-boards called tables, and showed that there the game might be

played. From their colour, which was red, and the similarity to a lattice, it

was corruptly called red lattice.

"_ his sign pulled down, and his lattice borne away."

So in "A Fine Companion," one of Shakerly Marmion's plays:— 'A waterman's widow,

at the sign of the Red Lattice in Southwark."

Nothing has occasioned so much discussion amongst the commentators, as

Falstaff's " Sack and Sugar," sack itself being supposed to be a sweet wine.

That it was the custom, however, even in that case, to give additional sweetness

by adding sugar, is attested by several old writers. Gascoigne observes— that

"wine itself was not sufficient"— but " sugar, lemons, and spices must be

drowned in the wine, which I never observed in any other place or kingdom to be

used for that purpose." Fynes Moryson, a Scotch traveller, 1617, notices at that

day, the mixing of sugar with every species of wine:— " Gentlemen drawers," says

he, " with wine mix sugar; which I never observed in any other place or kingdom

to be used for that purpose. And because the taste of the English is thus

delighted with sweetmeats, the wine in taverns (for I speak not of merchante's

or gentlemen's cellars) are commonly mixed at the filling thereof to make them

pleasant."

We find also, from Sir John's comments on his favorite sack, that he added not

only sugar, but a toast to it; that he had an implacable aversion to its being

mulled with eggs, vehemently exclaiming—

"I'll no pullets sperm in my brewage;" and that he abominated its sophistication

with lime, declaring that a " coward is worse than a cup of sack with lime in

it."— An expedient which the vintners used to increase its strength and

durability.

The act 7 Edward VI "For th' avoyding of many inconveniences, muche evil rule,

and commune resorte of misruled persones, used and frequented in many taverns of

late newly sett uppe in very greate numbre in backe lanes, corners, and

suspicious places within the cytie of London, and in divers other townes and

villages within this realm;" after regulating the price and quantity of wine

which should be sold by retail dealers, viz:— that no more than 8d. per gallon,

should be taken for any French wines— " by any maner of meanes, colour, engine,

or crafte, &c." limited the yearly consumption of wine in private houses, to ten

gallons each person, unless possessed of 100 marks per annum, or 1000 marks in

property,— and ordered, that there should not be more than two licenced taverns

in any one town, nor " any more or greater number in London of such tavernes or

wine sellers by retaile, above the number of fouretye tavernes or wyne sellers;"

being less than two, upon an average to each parish. Nor did this number much

increase afterwards, for in a return made to the vintner's company late in

Elizabeth's reign, there were only one hundred and sixty-eight in the whole city

and suburbs.

As there is no reason to suppose but that the old Bush, Aldersgate, was

continued as one of these "Select"— we may consider this as no small proof, in

addition to others, of its importance. We know at least, from Stowe's

description, that a house on this site, evidently a public one, was considerably

enlarged a few years afterwards; and there appears no place to which it will

apply but the Bush.

"This gate" (Aldersgate) "hath been at sundry times increased with building,

namely, on the south or inner side, a great frame of timber * hath been added

and set up, containing divers large rooms and lodgings,"— as these "large rooms

could only be wanted in a house of public entertainment, the fair inference is,

that this was an enlargement of the Bush; and agreeably to this fact, we find in

the earliest plan we have of the metropolis, that by Ralph Aggas, A. D. 1560, a

single house only, marked on this site, as adjoining the inner side of

Aldersgate. The delineation is rude— but bears us out in the idea that it was

intended as a representar tion of this tavern.

* A frame of timber was then synonymous with house; the houses being at this

time for the most part of wood lathed and plastered, with overhanging stories,

as we still see them in some of the old streets.

The variety of wines in Elizabeth's reign, has not since been exceeded, and

perhaps even equalled.

Harrison mentions fifty-six French, and thirty-six Spanish, Italian, and other

wines; to which must be added several home-made wines, as ipocras, clary, breket,

and others.

From this period, and including the reign of James, taverns appear to have been

very numerous ; and says bishop Erle, who wrote at the time, "to give you the

total reckoning of it, they're the busy man's recreation, the idle man's

business, the melancholy man's sanctuary, the stranger's welcome, the inns of

court men's entertainment, the scholar's kindness, and the citizen's curtesy."

He adds, (as must be the case with all such accommodations when abused,) " the

consumer and corrupter of the afternoon, and the murderer or maker away of a

rainy day."

The Boar's Head, Eastcheap, and the Mermaid, Cornhill— immortalized by

Shakspeare, Ben Jonson, and by Fletcher, are enumerated in a long list of

taverns given us in an old black letter 4to. of the reign of Charles I.

entitled, "Newes from St. Bartholomewe's Fayre." The title is lost, but the

following are mentioned as some of the signs:—

"There hath been great sale and utterance of wine,

Besides beere and ale and ipocras fine;

In every country, region, and nation—

Closely at Billingsgate at the Salutation,

And Bore's Head near London stone, \

The Swan at Dowgate, a taverne well knowne,

The Miter in Chepe, and then the Bull Head,

And suche like places that make noses red;

The Bore's Bead in Old Fish Street, Thrte Cranes in the Vinttee,

And now of late St. Martin's in the sentree,

The Windmill in Lothbury, the Ship at the Exchange,

King's Head in New Fish Streete, where roysters do range,

The Mermaid in Cornhill, Red Lion in the Strand,

Three Tuns Newgate Market, Old Fish Street at the Swan.

This enumeration omits the Bush, and many of the oldest London signs, as the

Pope's Head, the London Stone, the Dagger, the Rose and Crown, &c. which most

likely are mentioned in another part of it, at least they should, if it pretends

to give anything like a general catalogue of the taverns then known. From the

supposed age of different signs, it will also appear, that most of the above

were of comparatively late date; for Mr. Fosbroke tells us rightly, in his

notices of tavern signs, after stating that the Bush was the oldest,— that the

Bull, Ram, Angel, Red Lion, and such like, were of after growth, and evidently

heraldic, as supporters of arms, taken from respect to some great lord or

master, and formed upon the nature of dependants and servants wearing badges of

their lord's arms.

The Painted Tavern, adjoining the Three Cranes, in that Vintry, is mentioned by

Stowe as existing in the time of Richard II. It nearly adjoined the great house

termed the Vintry, underneath which were extensive wine vaults, for depositing

such wine as should be landed at the wharf. The story of Sir Henry Picard,

vintner and lord mayor, feasting here four kings, in 1350, is well known.

In the play— " If You Know not Me, You Know Nobody," with the "Building of the

Royal Exchange," &c. 1608, the apprentices of old Hobson, a rich citizen, in

1560, frequent the Rose and Crown, in the Poultry, and the Dagger, in Cheapside.

Enter Hobson, Two Prentices, and a Boy.

1 Pren. Prithee, fellow Goodman, set forth the ware, and looke to the shop a

little. I'll but drink a cnp of wine with a customer, at the Rose and Crown in

the Poultry, and come again presently.

2 Pren. I must needs step to the Dagger in Cheape, to send a letter into the

country unto my father. Stay, boy, you are the youngest prentice; look you to

the shop,

Ben Jonson found the best canary at the "Swanne," by Charing Cross, and was so

delighted with the drawer's attention, that in some extempore lines made by him,

by way of grace, before king James, and which Aubrey has given in his "Lives,"

he contrived to lug in the lad's name with his own, as a conclusion:—

"Our king and queen the Lord God bless,

The palsgrave, and the lady Besse;

And God bless every living thing,

That lives, and breathes, and loves the king.

God bless the council of estate,

And Buckingham the fortunate.

God bless them all, and send them safe—

And God bless me, and God bless Ralph."

The king was anxious to know who Ralph was, and when informed by the poet, that

it was the drawer at the Swan, who drew him better canary than he could get any

where else, laughed, it is said, heartily at the conceit.

Many curious particulars attach to the wine houses of this period. Amongst

others, a passage in "Look About You," (1600) says "The drawers kept sugar

folded up in paper, ready for those who called for sack;" and we further find in

other old tracts, that the custom existed of bringing two cups, of silver, in

case the wine should be wanted to be diluted, and that this was done by

rose-water and sugar, generally about a penny-worth. A Sharper in the " Belman

of London," being described as having decoyed a countryman to a tavern, "calls

for two pintes of sundry wines, the drawer setting the wine with two cups, as

the custome is, the sharper tastes of one pinte, no matter which, and finds

fault with the wine, saying, 'tis too hard, but rose-water and sugar, would send

it downe merrily'— and for that purpose he takes up one of the cups, telling the

stranger he is well acquainted with the boy at the barre, and can have

two-pennyworth of rose-water for a penny of him; and so steps from his seate;

the stranger suspects no harme, because the fawne guest leaves his cloake at the

end of the table behind him,— but the other takes good care not to return, and

it is then found that he hath stolen ground, and out-leaped the stranger more

feet than he can recover in haste, for the cup is leaped with him, for which the

wood-cock, that is taken in the springe, must pay fifty shillings, or three

pounds, and hath nothing but an old threadbare cloake not worth two groats to

make amends for his losses."

Another similar low scene of villiany, and laid at one of the taverns of this

period, is told by the above old author. It is the account of a countryman, who

is is decoyed into one of those places by three associates,— and of course

plucked.

"The stage on which they play their prologue, is either in Fleet Street, the

Strand, or Paule's, and most commonly in the afternoon, when countrie Clyents

are at most leasure to walke in those places, or for dispatch of their business

travel from lawyer to lawyer, through Chancerie Lane, Holborne, and such like

places. In this heat of runing to and fro, if a plaine fellowe, well and

cleanely apparrelled, either in home-spun russet or frieze, (as the season

requires,) with a side pouch at his girdle, happen to appear in his rusticall

likeness. 'There is a couzin,' says one, at which word out flyes the decoy, and

thus gives the onset upon my olde penny-father. "Sir, God save you! you are

welcome to London! How doe all good friends in the countrie? I hope they be

well? The russetting amazed at these salutations of a stranger replies,' Sir,

all our friends in the countrie are in health; but pray pardon me; I know you

not, believe me;—' No!' answers the other, 'are you not a Lancashire man?' or of

such a countrie? If he saies, 'yes,' then seeing the fish nibbles, he gives him

more line to play with; if he say,' no,' then attacks he him with another

weapon, and sweares soberly,' In good sooth, Sir, I know your face, I am sure

wee have bene merie together; I pray (if I may beg it without offence,) bestow

your name upon mee, and your dwelling-place!' The innocent man, suspecting no

poison in this gilded cup, tells bim presently his name and abiding—by what

gentleman he dwells, &c. which being done, the decoy, for thus interrupting him

in his way, and for the wrong in mistaking him for another, offers a quart of

wine. If the cozen be such an asse to goe into a Taverne, then he is sure to bee

' unkled'; but if he smack my decoy, and smell gunpowder-traines, yet wil not be

blown up, they part fairly; and to a comrade goes the decoy, discovering what he

hath done, and acquaints him with the man's name, countrie, and dwelling; who

hastening after the countryman, and contriving to cross his way and meet him

full in the face, takes acquaintance presently of him, salutes him by his name,

inquires how such and such a gentleman doe that dwell in the same town by him,

and albeit the honest hobnail wearer can by no means bee brought to remember

this new friend, yet will he, nill he, to the Taverne he sweares to have him,

and to bestowe upon him the best wine in London; and being come here, they are

soon joined by two or three associates, who drop in as strangers, and, who

having by some trick or other contrived to fleece the simpleton, and make him

completely drunke, steal off one by one, and meet at another taverne to share

their plunder;— which is the epilogue to their comedie, but the first entrance

(scene) to the poore countryman's tragedie."

The following from the "Microsmography" of Dr. Erle, could only apply to the

lowest species of tavern.—

"A taverne is a degree, or if you will, a paire of staires above an ale-house,

where men get drunk with more credit and apology. If the vintner's rose be at

door, it is sign sufficient, but the absence of this is supplied by the

ivy-bush."

And again :—

"The whole furniture of these places consists of a stool, a table, and a pot de

chambre."

The concluding article of the list reminds one of Falstaff's calling out to "

empty the jordan."

That the above is mere satire, however, or that it must apply rather to

something like our modern winecellars than to taverns, will be evident from what

Dekker tells us near this very time :—

"They had," says he, "regular ordinaries, and of three kinds, namely, an

ordinary of the longest reckoning, whither most of your courtly gallants do

resort; a twelve-penny ordinary, frequented by the justice of the peace and

young knight; and a threepenny ordinary, to which your London usurer, your stale

batchelor, and your thrifty attorney doth resort."

That the conjunction of vintner and victualler had now become common, and would

require other accommodations than those mentioned by the bishop, even in the

poorest houses of entertainment, is also shewn in the play of the " New Way to

Pay Old Debts," where Justice Greedy makes Tapwell's keeping no victuals in his

house, an excuse for pulling down his sign.

"Thou never hadst in thy house to stay men's stomachs,

A piece of Suffolk cheese, or gammon of bacon,

Or any esculent, as the learned call it,

For their emoulument, but sheer drink only.

For which gross fault I here do damn thy licence,

Forbidding thee henceforth to tap or draw;

For instantly I will in mine own person,

Command the constable to pull down thy sign,

And do't before I eat.''

And the decayed vintner, who afterwards applies to Wellborn for payment of his

tavern score, answers on his enquiring who he is.

"A decay'd vintner, Sir,

That might have thriv'd, but that your worship broke me,

With trusting you with muscadine and eggs,

And five-pound suppers, with your after drinkings,

When you lodged upon the Bankside."

Another corroboration of these establishments then being on a very superior

footing, is given us also by Dekker. It was, he informs us, usual for taverns,

especially in the city, to send presents of wine from one room to another as a

complimentary mark of friendship, "Enquire," directs he, "what gallants sup in

the next room; and if they be of your acquaintance, do not, after the city

fashion, send them in a pottle of wine and your name." This custom too is

recorded by Shakespeare, as a mode of introduction to a stranger. When Bardolph

at the Castle Inn, Windsor, addressing FalstafF says, " Sir John, there's a

master Brooke below would fain speak with you, and would be acquainted with you,

and hath sent your worship a morning's draught of sack;" a passage which Mr.

Malone has illustrated by the following contemporary anecdote. "Ben Jonson," he

relates, "was at a tavern, and in comes Bishop Corbet, (but not then a prelate,)

into the next room. Ben Jonson calls for a quart of raw wine, and gives it to

the tapster. "Sirrah," says he, " carry this to the gentleman in the next

chamber, and tell him I sacrifice my service to him;" the fellow did so, and in

the same words. "Friend," says Dr. Corbet, " I thank him for his love, but

prithee, tell him from me, that he is mistaken, for sacrifices are always

burnt."

Many 0f the London taverns were indeed of high respectability: the famous

Robinhood society is said, in the history of that establishment, (8vo. 1716,) to

have began from a meeting of the editor's grandfather with the great Sir Hugh

Middleton, of New River memory, at the London Stone Tavern in Cannon Street,

(therein stated, but certainly not correctly, to be the oldest in London;)

whence the society afterwards removed successively to the Essex Head, Devereux

Court, Temple, and finally to the Robinhood, Butcher Row, from whence they took

name. King Charles II. was introduced to this society, disguised, by Sir Hugh,

and liked it so well that he came thrice afterwards. "He had," says the

narrative, " a piece of black silk over his left cheek, which almost covered it;

and his eyebrows, which were quite black, he had by some artifice or other

converted to a light brown, or rather flaxen colour; and had otherwise disguised

himself so effectually in his apparel and his looks, that nobody knew him but

Sir Hugh by whom he was introduced."

The following are named as celebrated London taverns, in the newspapers of the

civil-war period:—

The Sun, Cateaton Street.

Tobacco Boll, Smithfield.

Harp and Ball, Charing Cross.

Bam, Smithfield.

Plough, St. Paul's.

Crane, ditto.

Haymakers, Whitechapel.

Spotted Leopard, Aldersgate Street.

The Dog and Bull, Fleet Street.

Turk's Head, Cornhill.

Anchor and Mariner, Tower Hill.

Goat's Neck, Ivy Bridge, Strand.

Hercules Pillars, Fleet Street.

Unicorn, Cornhill.

Ship, St. Paul's

Greyhound Tavern, Blackfriars.

Gun, Ivy Lane.

Maidenhead and Castle, Piccadilly.

Black Spread Eagle, Fleet Street.

Stag's Head, St. Paul's.

Crown and Garter, St. Mary's Hill.

Elephant and Castle, Temple Bar.

Goat's Head, St. James's.

Hat and Feathers, Strand.

Ned Ward, London Spy, 1709, mentions the Rose tavern, Poultry, anciently the

Rose and Crown, as existing in his time, and famous for good wine.—

"There was no parting without a glass, so we went into the Rose tavern in the

Poultry, where the wine, according to its merit, had justly gained a reputation;

and there, in a snug room, warmed with brash and faggot, over a quart of good

claret, we laughed over our night's adventure."

The Angel, Fenchurch Street, and the King's Head, Chancery Lane, also come in

for a share of our author's praise :—

From hence, pursuant to my friend's inclination, we adjourned to the sign of the

Angel, in Fenchurch Street, where the vintner, like a double-dealing citizen,

condescended as well to draw carmen's comfort, as the consolatory juice of the

vine."

"Having at the King's Head well freighted the hold of our vessels with excellent

food and delicious wine, at a small expence, we scribbled the following lines

with chalk upon the wall, then took our departure, and steered for a more

temperate climate:—

"To speak the truth of my honest friend Ned,

The best of all vintners that ever was made;

He's free of his beef, and as free of his bread,

And washes down both with a glass of rare red

That tops all the town, and commands a good trade;

Such wine as will cheer np the drooping King's Head,

And brisk up the soul, though the body's half dead."

Besides uniting the business of a vintner and victualler, and even adding, as

the above extracts informs us, the drawing of " carmen's comfort," we find in

other respects the whole economy of our ancient taverns changed about this time.

Among other alterations, the facetious Ned Ward informs us, that the bar-maid,

with a number of waiters, had completely superseded the ancient drawers and

tapsters :—

"As soon as we came to the bar, a thing started up all ribbon, lace, and

feathers, and made such a noise with her bell and her tongue together, that had

half a dozen paper-mills been at work within three yards of her, they'd have

signified no more to her clamorous voice than so many lutes to a drum, which

alarmed two or three nimble-heeled fellows aloft, who shot themselves down

stairs with as much celerity as a mountebank's mercury upon a rope from the top

of a church steeple, every one charged with a mouthful of coming, coming,

coming!"

He further illustrates the qualifications of the barmaid, (generally the

vintner's daughter,) in another place, by describing her as "bred at the dancing

school, becomes a bar well, steps a minuet finely, plays sweetly on the

virginals, 'John come kiss me now, now, now,' and is as proud as she is

handsome;" in fact, a second Polly in the Beggar's Opera, only less amiable.

Tom Brown at the same time speaks of the flirt of the bar-maid:—

"That fine lady that stood pulling a rope, and screaming like a peacock against

rainy weather, pinned up by herself in a little pew, all people bowing to her as

they passed by, as if she was a goddess set up to be worshipped, armed with the

chalk and sponge, (which are the principal badges that belong to that honourable

station you beheld her in,) was the bar-maid."

And of the nimbleness of the waiters, Ward says in another place:—" That the

chief use he saw in the Monument was, for the improvement of vintner's boys and

drawers, who came every week to exercise their supporters, and learn the tavern

trip, by running up to the balcony and down again."

Owen Swan, at the Black Swan tavern, Bartholomew Lane, is thus apostrophised by

Tom Brown for the goodness of his wine:—

"Thee Owen, since the God of wine has made

Thee steward of the gay carousing trade.

Whose art decaying nature still supplies,

Warms the faint pulse, and sparkles in our ejes.

Be bountiful like him, bring t'other flask,

Were the stairs wider we would have the cask.

This pow'r we from the God of wine derive,

Draw such as this, and I'll pronounce thou'lt live."

Speaking of Queen Anne's proclamation against vice and debauchery, in 1703, the

paper called the Observer says:—" The vintners and their wives were more

particularly affected by it, some of the latter of which had the profit of the

Sunday's claret to buy them pins, and to enable them every now and then to take

a turn with the wine merchant's eldest prentice to Cupid's garden on board the

Polly." *

The coffee-houses about the time of the restoration first began to supersede the

old English tavern, and though it subsisted as we have shewn long after that

period, and is even now not extinct, it is under completely different

modifications. Of these coffee-houses, as also chocolate-houses, (which latter

began to spring up about the reign of Anne,) the most celebrated at the west end

of the town were,— the Cocoa Tree, and White's, St. James's; the Smyrna, and the

British Coffee House; which were all so near that in less than an hour you might

see company in them all. They were formerly carried to these places in chairs

and sedans, and then at this time had their different parties. A whig would no

more go to the Cocoa Tree or Ozindas, than a tory would be seen at the coffee

house of St. James's. The Scots generally frequented the British, and a mixture

of all sorts unto the Smyrna. There were other little coffee-houses much

frequented in this neighbourhood; Youngman's for officers, Oldman's for

stock-jobbers, paymasters, and courtiers, and Littleman's for sharpers. After

the play, the best company generally went to Tom's and Will's coffee-house, near

adjoining, where there was playing at picquet, and the best of conversation till

midnight. Here you would see blue and green ribbons and stars sitting familiarly

with private gents, and talking with the same freedom as if they had left their

quality and degrees of distance at home. The most celebrated city coffee-houses

were Tom's, Garraway's, Robin's, and Jonathan's; Button's is well known as the

resort of Addison, Pope, &c. great wits of Anne and George the first's days.

* Caper's Gardens on board the Folly, the spot where Waterloo I Road Church now

stands.

To the above we may add as a cause of the decline of taverns, the general

introduction of malt liquor as a common beverage, the high duties put upon

wines, and above all the immoderate use of ardent spirits. Gin, about the

beginning of the reign of George II. may be said to have almost inundated the

meropolis, from the cheap rate at which it was sold, and occasioned Hogarth to

attempt to counteract its pernicious effects, in his admirable prints of Gin

Street and Beer Street. In the present day we still find several respectable

houses bear the name of taverns, but the nature of their trade is totally

altered from what it was anciently, and is either merged in the more modern

business of the coffee-house keeper or that of the licenced victualler.

We return to the Mourning Bush.—

No mention occurs of this tavern in any of the publications we have met with,

from the period when the anecdote is told of its loyal owner on the beheading of

Charles I., till the year 1719, when we find its name changed to the Fountain.

Whether this was caused by any political feeling against the then exiled House

of Stuart, or was merely the capricious whim of the proprietor, we cannot learn,

possibly it might have relation to a curious spring oh this spot thus mentioned

by Stowe:—

"Also on the east side" (i. e. of the gate) "is the addition of one great

building of timber, with one large floor, paved with stone or tile, and a well

therein, curb'd with stone, of a great depth, and rising into the said room two

stories high from the ground; which well is the only peculiar note belonging to

this gate; the like perhaps not be found in the city." ^

Under this denomination of the Fountain, it is mentioned in Tom Browne's works,

satirically, with four or five topping taverns of the day, whose landlords are

charged with fully understanding the art of "doctoring" as it is called, their

wines, but whose trade nevertheless was so great that they stood fair for the

alderman's gown. The mention is contained in an article purporting to be a

letter from an old vintner in the city to a one newly set up at Covent Garden,

and is in the way of advice.— The trade of a vintner, the writer assures his

friend, "is a perfect mystery"— (for that is the term, he observes, which the

law bestows upon it.)— He adds, — "Now as all in the world are wholly supported

by hard and unintelligible terms, you must take care to christen your wines by

some hard names, the further fetched so much the better, and this policy will

serve to recommend the most execrable scum in your cellar. I could name several

of our brethren to you, who now stand fair to sit in the seat of justice, and

sleep in their golden chain at churches, that had been forced to knock off long

ago, if it had not been for this artifice. It saved the Sun from being eclipsed,

the Crown from being abdicated, the Rose from decaying, and the Fountain from

being drawn dry, as well as both the Devil's from being confined to utter

darkness. *

Twenty years later, viz. in Hive's large plan of Aldersgate Ward, 1739-40, we

find the Fountain changed to the original name of this house, " The Bush

Tavern," The Fire of London had evidently curtailed at this time its ancient

extent, (judging from the way it is represented in Aggas's view, as well as from

the cellarage,) and instead of reaching from Aldersgate to St. Anne's Lane, it

has, according to the scale, only about fifty feet frontage, and is divided from

the corner house or houses by a passage, which leads to the top of the ancient

alley or entry, at present forming the back way to the Mourning Bush from St.

Anne's Lane.

* The Devil Tavern stood on the site of Child's Place, next Temple Bar, and is

immortalized in Ben Jonson's Leges Conviviales, which he wrote for the

regulation of a club of wits, held here, in a room he dedicated to Apollo, and

over the chimney-piece of which they were preserved. The sign was St. Dunstan

tweaking the devil by the nose with a hot pair of tongs. In Jonson's days this

tavern was kept by Simon Wadloe, whom in a copy of verses over the door of the

Apollo he dignified with the title of king of skinkers (tapsters or drawers).

"Hang up all the poor hop drinkers,

Cries old Sym. the king of skinkers."

It is said in one of Ben's trips to the Devil tavern, he observed a country lad

gaping at a grocer's shop just by, and was told by him, that he "was admiring

that nice piece of poetry over the shop." "How can you make that rhyme?" said

the bard. "Why thus," replies the lad, whose name was Ralph:

"Coffee and tea

To be s-o-1 d."

This so pleased Jonson, that Ralph was taken into his service immediately, and

continued with him till his death. Query.— was coffee or tea then in use in

England?— we think not. The anecdote, however, may apply to some later name.

The exterior of the tavern is at the same time shewn in a small marginal print

of the south side of Aldersgate. It has the precise character of the larger

houses erected after the Fire of London, being constructed of brick, with heavy

stone window frames and dressings. There are balconies to the two principal

windows of the first story; and the house from immediately adjoining the gate,

has in some measure, the effect of an attached ornamental building to it. The

view and plan are shewn in the accompanying plate.

The last notice of this house as a place of entertainment, occurs in Maitland's

History of London, (p. 767, ed. 1772,) in the account of the boundaries of

Aldersgate Ward, where it is described as the Fountain Tavern, commonly called

the Mourning Bush :—

"the Fountain, commonly called the MournIng Bush, which has a back door into St.

Anne's Lane, is seated near unto Aldersgate."

The modern fitting up of the Mourning Bush deserves to be noticed for the credit

it reflects on the talents of Mr. Cottingham, the architect, as well as on the

spirit of Mr. Williams, the proprietor; and we consider it only a tribute due to

both, for the politeness with which they have assisted our researches on this

spot, to conclude with this mention of them:—

In the basement of the house, are the original wine vaults of the old Bush

Tavern, the whole of which are judiciously retained, many of the walls being six

feet thick, and bonded throughout with Roman brick. The ground floor embraces a

spacious bar, its ceiling beautifully painted in imitation of one discovered at

Herculaneum, and dining and coffee rooms for the accommodation of the numerous

working classes whose daily avocations call them into the immediate vicinity of

the New Post Office. The one-pair floor is entirely occupied with spacious

coffee and dining rooms, capable of accommodating one hundred and fifty persons.

In the great coffee room is an elegant range of book-cases containing a

selection of the best geographical works, books of travels, &c. besides all the

reviews and periodicals of the day, accompanied by a splendid set of Smith's

large roller maps of all parts of the globe. In the two-pair are elegant dining

rooms for small parties, and lodging rooms for single gentlemen.

One of the above new rooms, forty-five feet long, and proportionably broad,

which is called "The Shakespeare Dining Room, is particularly to be admired; it

is fitted up in the most elegant manner; — on the south end is a bust of the

immortal bard, modelled from the original on his monument at

Stratford-upon-Avon: it is supported on antique trusses of winged Victories,

moulded from the celebrated examples at the British Museum, and beneath in an

elegant time-piece inlaid with scroll-work in brass ; a superb chimney glass of

large dimensions finely reflects these objects at the reverse end of the room.

It may be mentioned as rather a singular coincidence, that the old sign of this

house, the Mourning Bush, placed to commemorate the death of King Charles the

First, was revived, or in other words the house was opened again as a tavern

under its present re-licencing, on the very day of the death of King George the

Fourth— being a distance of one hundred and eighty-two years between the two

melancholy events. We wish for the landlord's sake, the new establishment may

commence as auspiciously as the new reign.

And Last updated on: Wednesday, 02-Oct-2024 13:06:59 BST

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content