Search london history from Roman times to modern day

337

Let us pass on to consider the daily life of the people. To begin with, they were a busy people; there were no idle men: everybody followed some pursuit; there were the wholesale merchants, the retailers, and the craftsmen. I have submitted a rough division of London streets into belts. In thinking of the aspect of the City, understand that there were no shops in the streets at all; nor was there any crying of things up and down the streets. All the retail trade was carried on in the markets, West Chepe and East Chepe, and the wholesale trade was conducted in Thames Street beside the quays and the warehouses.

The markets were, first, Billingsgate for fish, salt, onions, other fruits and roots, wheat and all kinds of grain; every great ship paid for “standage” twopence; every small ship one penny; a lesser ship one penny; a lesser boat a halfpenny; for every two quarters of corn the King was to have one farthing; on a comb of corn, one penny; on every tun of ale going out of England, fourpence; on every thousand herrings, a farthing, etc. Queenhithe, or Edred’s Hithe, was probably of later date than Billingsgate.

London had already among her inhabitants many merchants of foreign descent; they came from Caen and from Rouen, from Germany and from Flanders. The “Emperor’s Men” had already set up their steelyard and begun to trade within walls of their own, protected by strong gates, and possessed of extensive privileges. The men of Lubeck, Hamburg, and the Flemings, who did not belong to the “Gildhalla Teutonicorum,” also set up their fortified trading-houses. I do not suppose that the connection which was afterwards established between London and the country gentry had yet been established; indeed it is impossible, seeing that most of the manors of England had been granted to the Norman followers of King William, and as yet these new masters of the soil were in no sense English. But, as we have seen, many of the nobles already had their town houses in London.

In the “Dialogus Scaccario,” printed in full in Madox’sHistory of the Exchequer, and in Stubbs’sSelect Charters, there is a most valuable passage on the fusion of the Normans and the English. It is as follows:—

338

“In the early condition of the Kingdom after the Conquest, those who were left of the subject English used to lay snares secretly against the race of Normans suspected and hateful to them: here and there, wherever the chance offered, they murdered Normans in their forests and remote places, in punishment for which, when the Kings and their ministers for several years raged against the English with exquisite modes of torture, yet found that they would not wholly desist, it was at length resolved that the Hundred in which a Norman was found murdered, if the murderer was not discovered or took to flight, should be condemned to pay a large sum of money, sometimes as much as thirty-six or even forty-three pounds, according to the character of the place and the frequency of the crime....”

“Now, however, the English and the Normans living together and intermarrying with each other, the two nations are so mixed that it is difficult to distinguish, among free men, who is English and who is Norman by descent.”

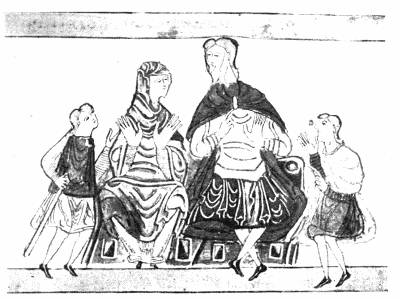

The fusion of the races was more easy in London than in the country, partly because the Normans had already been settled in the place and were carrying on the very considerable trade which existed with Rouen, Caen, and other northern ports: partly, because there was no rankling sense of injury, such as that which filled the hearts of dispossessed Saxon Thanes. The Norman king kept his word with London; he oppressed no citizen; he deprived no citizen of his property. Moreover, the Normans appear to have taken the lead in many things. Their superior refinement has been somewhat exaggerated, especially when we read of the accomplishments and the learning of the Anglo-Saxon ladies. But there can be no doubt that they introduced habits of temperance in the matter of strong drink. The Norman merchant was held in honour by the Norman knight, and the Norman noble had his town house in the City. Young Thomas Becket was a friend of Richer de l’Aigle of Pevensey; ecclesiastical dignitaries were his father’s guests; and in the chapter which follows on a Norman family, we shall see how they intermarried—Saxon and Norman, noble and burgher.

FitzStephen’s account, though most interesting, leaves out a great many things which we should like to know. He brings before our eyes a city cheerful and busy: the young people delighting in games of all kinds, especially archery, wrestling, mock fights, skating; he shows us a place of great plenty and containing within its walls as much freedom and as much happiness as any mediæval city could expect; he shows us the craftsmen living each in his own quarters; he shows us the monastic houses and the schools of children; he shows us a town in which all went well so long, he says, with significance, as there was a good king. Now the Norman kings were not without their faults, but one thing must be allowed them,—they were strong kings, and at this time339 and for many centuries to come, London wanted above all things a strong king, and if you look back at history you will find that a strong king meant a just king. In fact, though we are as yet far off from an ideal London, FitzStephen makes us understand that the people already possessed in Norman London an amount of liberty which was greater than that enjoyed by any city of France or Spain, and equal probably to that enjoyed by the people of Ghent and Bruges.

London has always been a City of great plenty. As yet the stretches of foreshore and marsh all down the river were uninhabited, as most of them remain to the present day. All these marshes abounded with birds innumerable: the river was full of fish—fish of all kinds; the supplies of cattle and of sheep and swine came from the meadows belonging to Westminster Abbey, and from the farms of Middlesex. The forest of Middlesex, which began at Islington, stretched north over an extensive tract; the forest of Essex was a continuation to the east, covering what were afterwards Epping and Hainault Forests; the villages of Essex and Middlesex were clearings in the forest. I suppose that the people bred horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs for the London markets.

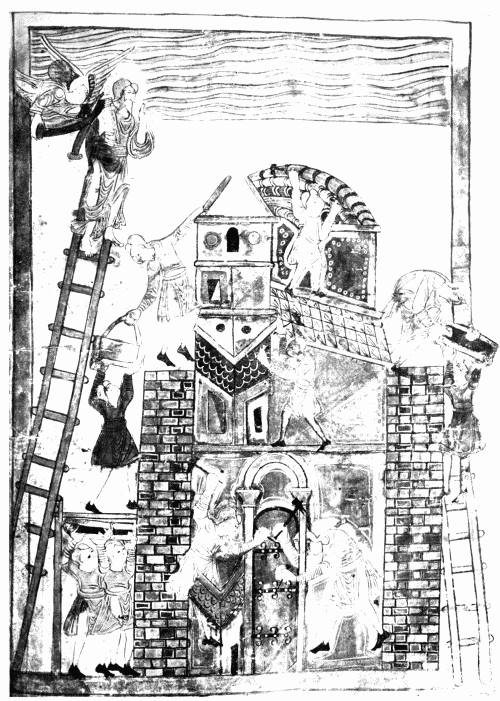

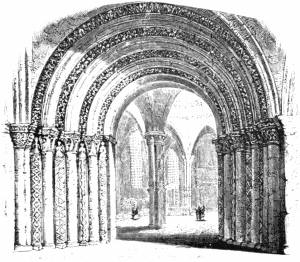

If the north part of London, where the craftsmen worked, was picturesque with the cottages among the trees, the south part was also picturesque, for the houses of the merchants were there, each with its hall and its garden. Churches stood everywhere. Most of them were quite small, plain village churches; here and there a Saxon church, like that at Bradford on Avon, narrow and dark, no glass in the windows, no pavement on the floor; and down the narrow lanes we could watch the river with the ships going up and down, the Yeo heave Ho! of the outward-bound, and the hymn to the Virgin for safety340 on the voyage from those who worked their way up with the flood tide to deep anchor below the bridge.

As for the people of the City, I venture to quote my own words from another book (London, p. 68):—

“It is an evening in May. What means this procession? Here comes a sturdy rogue marching along valiantly, blowing pipe and beating tabor. After him, a rabble rout of lads and young men, wearing flowers in their caps, and bearing branches and singing lustily.

The workman jumps up and shouts as they go past; the priest and the friar laugh and shout; the girls, gathering together, as is the maidens’ way, laugh and clap their hands. The young men sing as they go and dance as they sing. Spring has come back again—sing cuckoo; the days of light and warmth—sing cuckoo; the time of feasting and of love—sing cuckoo. The proud abbot, with his following, draws rein to let them pass, and laughs to see them—he is, you see, a man first and a monk afterwards. In the gateway of his great house stands the Norman earl with his livery. He waits to let the London youth go by. The earl scorns the English youth no longer; he knows their lustihood. He can even understand their speech. He sends out largesse to the lads to be spent in the good wines of Gascony and of Spain; he joins in the singing; he waves his hand, a brotherly hand, as the floral greenery passes along; he sings with them at the top of his voice—

Presently the evening falls. It is light till past eight; the days are long. At nightfall, in summer, the people go to bed. In the great houses they assemble in the hall; in winter they would listen to music and the telling of stories, even the legends of King Arthur. Walter Map or Mapes will collect them and arrange them; and the French romances, such as ‘Amis et Amils,’ ‘Aucassin et Nicolette,’ though these have not yet been written down. In summer they have music before they go to bed. We are in a city that has always been fond of music. The noise of crowd and pipe, tabor and cithern, is now silent in the streets. Rich men kept their own musicians. What said Bishop Grossetête?—

He who looks and listens for the voice of the people in these ancient times hears no more than a confused murmur: one sees a swarm working like ants; a bell rings, they knock off work; another bell, they run together, they shout, they wave their hats; the listener, however, hears no words. It is difficult in any age—even in the present day—to learn or understand what the bas peuple think and what they desire. They want few things indeed in every generation; only, as I said above, the three elements of freedom, health, and just pay. Give them these three, and they will grumble no longer. When a poet puts one of them on his stage and makes him act and makes him speak, we learn the multitude from the type. Later on, after Chaucer and Piers Plowman have spoken, we know the people better—as yet we guess at them, we do not even know them in part. Observe, however, one thing about London—a thing of great significance. When there is a Jacquerie—when the people, who have hitherto been as silent as the patient ox, rise with a wild roar of rage—it is not in London. Here, men have learned—however imperfectly—the lesson that only by combination of all for the general welfare is the common weal advanced. I think, also, that London men,342 even those on the lowest level, have always known very well that their humility of place is due to their own lack of purpose and self-restraint. The air of London had always been charged with the traditions and histories of those who have raised themselves: there never has been a city more generous to her children, more ready to hold out a helping hand: this we shall see illustrated later on: at present all is beginning. The elementary three conditions are felt, but not yet put into words.

We are at present in the boyhood of a city which after a thousand years is still in its strong and vigorous manhood, showing no sign, not the least sign, of senility or decay. Rather does it appear like a city in its first spring of eager youth. But the real work for Saxon and Norman London lies before. It is to come. It is a work which is to be the making of Great Britain and of America, Australia, and the Isles. It is the work of building up, defending, and consolidating the liberties of the Anglo-Saxon race.”

The question of slavery—whether it was common in London, and how long it lasted, is very difficult. When William told his new subjects that they were “law worthy,” he meant that the freemen were law worthy; none but freemen had any privileges at all. No one was allowed to have the freedom of the City unless he was known to be of free condition: and “even if, after he had received the freedom, it became known that he was a person of servile condition, through that same fact he lost the freedom of the City” (Liber Albus, p. 30). Witness the case of Thomas le Bedell, Robert le Bedell, Alan Underwoode, and Edmund May, who in the year 1301 lost their freedom because it was discovered that they held land in villeinage of the Bishop of London. The serfs or villeins held their land “in villeinage” or “in demesne.” They had no rights, and were the absolute property of their lords, who could dispossess them at any moment. Of the lower or dependent class, there were many subdivisions; all these were more or less serfs, holding their lands by the tenure of certain services; in the whole of England, according to Domesday Book, there were about 225,000 of these people, so that, if each of them had a wife and four children, there were a million and a quarter of cultivators of the soil who were also serfs. There is evidence, in plenty, that the condition of these people under the Normans rapidly improved; the Norman knight could not understand all the distinctions; he lumped the people all together and treated freemen and villani in much the same manner. Some of the villeins grew rich; some were emancipated formally; some passed through no form of emancipation; there remained, however, certain disabilities: they were not admitted to the freedom of the City of London, and we hear of complaints made about their admission to holy orders.

If we try to apply these facts to London we are baffled by a difficulty already indicated. Were there serfs in the City? If so, how many? What work did they undertake? Remember—a point already advanced—that in a city of many343 industries, if any industry or craft becomes regarded as especially the work of a slave, no freeman will ever after touch it; and if the slave is emancipated, he will never again do any of that work. But in London there has never been any prejudice against any kind of work. I cannot understand how London, at such a time, could have been composed entirely of freemen; but of the slaves, if there were slaves, I can find no trace, no memory, and no indication.

There is, however, the ancient Saxon custom that obtains in all free boroughs, if a villein fled from his master and found shelter within the walls for a year and a day unclaimed, he thereby became free. Now it is true that mere residence is not enough; a man must remain all that time unclaimed. May we not see in this law the determination that within the walls of London there should be no slave at all? In the Liber Albus all that I can find on the subject is that persons holding land in villeinage shall not be allowed the freedom of the City: this fact seems rather to point in the direction of allowing none but freemen in the City. In 1288 the attorney of the Earl of Cornwall preferred a claim in the Hustings against nine men, the bondmen of the Earl, runaways. The decision of the Court is not given, but it is clear that the men, who were villagers, hoped to remain unclaimed in London, and that they were disappointed. On the whole, therefore, I am of opinion that London would not allow any but freemen to live and work within her walls. And we may remember the clause (No. 24) in the Ordinances of the Council of 1103, to the effect that there shall be no more buying and selling of men, “which was hitherto accustomed.”

We have already seen what were the exports of London under the Saxons and Danes. Of course they remained the same under the Normans. Wool344 was the staple. England subsisted, so to speak, upon her wool. It went to Bruges, to Germany, and to Italy. The imports were, as before, wine from Germany and La Rochelle; spices, gums, cloth of gold, silk, and the finer weapons. New communications were opened up with the Continent, and England lost her ancient isolation, when her people could freely cross into Normandy, where their King was Duke. Trade was carried on by means of the tally. This was a piece of wood, generally willow wood, about nine inches long, cut into notches. Thus, a notch an inch and a half across at the widest or the outside part means £1000; an inch across £100; half an inch £20; and a long, narrow, sloping notch £10. Other convenient marks denoted single pounds, shillings, and pence.

The great fire of 1135 destroyed the whole of London from the Bridge to the Fleet river. It is sometimes said that this fire destroyed everything that was Saxon. Perhaps it did. But things moved very slowly in the eleventh century; we need not believe that there was any change at all in the buildings that succeeded Saxon London; the huts of the craftsmen, once burned down, were rebuilt on exactly the same plan, the frame houses of the merchant were rebuilt exactly as they had been before. What we may regret were the little Saxon churches—would that we had one or two of those left to us—and in addition, everything still remaining of Roman London. We shall never know what remains of Roman villas, temples, basilicas, baths, perished in this and other mediæval fires, of which there were so many.

It must have been mortifying to the English merchant that the whole of the foreign trade, the export and import trade, was carried on by strangers; the Port of London for a long time had no ships, or next to none, of her own. The Flemings and the German ships came and went in fleets too strong to be attacked; otherwise the narrow seas were swarming with pirates. There were English pirates, Norman pirates, and French pirates; none of them were anxious to respect a ship of their own nationality; it seemed as if by merely living in a seaport one became naturally a pirate. Our sailors were simply undisciplined pirates. When Henry the First raised a fleet, the men mutinied and half of them went over to the enemy. The only chance of the London merchants was to send out a fleet strong enough to fight and beat off these pirates. This, however, they could not do; therefore for many a year to come the foreign trade of London remained with the men of Hamburg, Cologne, and Bruges.

On the government of London at this period we have spoken fully in the second volume on Mediæval London, where will be found a chapter called “The Commune” (p. 11).

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content