Search london history from Roman times to modern day

321

The City at this time occupied the same area as the Roman Augusta. The conditions of marsh and moor on all sides remained very little changed from the prehistoric days when London had not yet come into existence save for beaten paths or roads leading to north-west and east, and a causeway leading south. Right through the middle of the town flowed the Walbrook, which rose in the moor and ran into the river by means of a culvert. In the Norman time the Walbrook was one of the chief supplies of water that the town possessed. London relied for her water on the Fleet river on the west, on the Walbrook in the midst, on wells scattered here and there about the City, and upon certain springs, of which we know little. At this day, for instance, there is a spring of water under the south-west corner of the Bank of England, which still flows, as it always has done, along the channel of the ancient Walbrook. But as yet there were no conduits of water brought into the town.

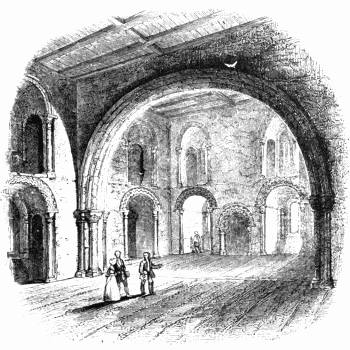

Within the town there were 126 parish churches, all of which belonged to Saxon London, a fact which is proved by the patron saints to whom they are dedicated. The Norman Conquest added nothing to the list of churches. Before the Conquest the only Religious House within the walls was that of St. Martin’s le Grand, which was a College of Canons (see p. 212). A legend describes the foundation of a small nunnery at the south end of the ferry over the river. There was also the Cathedral establishment. As yet there were no mendicant friars preaching in the street and begging in the houses, nor did any monastery rear its stately church or receive the offerings of the faithful. The parish church had no foundations or endowments of chantry, obit or day of memory. The Cathedral establishment was small and modest compared with that of the thirteenth century. The Bishop lived in his palace close to St. Paul’s. The Cathedral would be called a stately church even now; it was low with thick pillars and round arched windows, which were already filled with painted glass. The parish churches were quite small, and for the most part of wood: the name of All Hallows Staining, or All Hallows Stone, shows that it was an exceptional thing for a church to be built of stone.

There were two fortresses in the City, as we have seen, both belonging to the322 King. The modern idea of a street with its opposite row of houses all in line must be altogether laid aside when we go back to the eleventh century. It is, in fact, quite impossible to lay down a street as it actually existed at that time. The most important street in the City, Thames Street, did certainly possess a tolerably even line on its south side; the old course of the river wall and the quays compelled a certain amount of alignment; but on the north side the street was sometimes narrow, sometimes broad, because there was no such reason for an even line; sometimes a great house pushed out a gabled front into the street; sometimes a garden interposed or a warehouse stood back, leaving a broad space in front. As for regularity of alignment, no one thought of such a thing; even down to the reign of Queen Elizabeth only the main streets, such as Cheapside, possessed any such regularity. In one of the exhibitions, a few years since, there was a show which323 they called a street of Old London. The houses were represented as being all in line, as they would be to-day, or as they were in Cheapside in the time of Elizabeth. Considered as a street of Plantagenet London, the thing was absurd, but no one took the trouble to say so, and it pleased many.

On the north part of the City the manors, which were the original wards of the City, were still in the eleventh century held by families who had been possessed of them for many generations; even since the resettlement of the City by Alfred. The names of some of the old City families survive. For instance, Bukerel, Orgar, Aylwyn, Ansgar, Luard, Farringdon, Haverhill, Basing, Horne, Algar, and others. On the south part, along the river, it is probable that they had long since been sold and cut up, just as would happen in modern times, for building purposes. The northern quarter, however, was not so thickly built upon, and the manors still preserved something of a rural appearance with broad gardens and orchards. Therefore, in this quarter, the industries of the City found room to establish themselves. It must be remembered that a mediæval city made everything that was wanted for the daily life. In modern times we have separated the industries: for instance, the thousand and one things that are wanted in iron are made in Birmingham; our knives and cutlery are made in Sheffield; but in the eleventh century London made its own iron-work, its own steel-work, its own goldsmiths’ and silversmiths’ work, its saddlery, its leather-work, its furniture, everything. The craftsmen gathered together according to their trades: first, because the craft was hereditary by unwritten law and custom, so that the men of the same trade married in their trade, and formed a tribe apart; they were all one family; next, because there was but one market or place of sale for each trade, the saddlers having their own sheds or shops, the goldsmiths theirs, and so on; a separate324 craftsman, if it had been possible for such a man to exist, would have found it impossible to sell his wares, except at the appointed place. Of shops there were none except in the markets. Next, the workmen had to live together because they had in their own place their workshops and the use of common tools and appliances; and lastly, because a trade working for little more than the needs of the City must be careful not to produce too much, not to receive too many apprentices, and to watch over the standard of work. Every craft, therefore, lived together, under laws and regulations of its own, with a warden and a governing body. The men understood, long before the modern creation of trades unions, what was meant by a trades union; they formed these unions, not only because they were created in the interests of all, but because they were absolutely necessary for mere existence.

They lived, I say, together and close to each other; each craft with its own group of houses or cottages—perhaps mere huts of wattle and daub with thatched roofs and a hole in the roof for the smoke to go out. And they lived in the north part of London, because it was thinly populated and removed from those to whom the noise of their work might give offence. One proof of the comparative thinness of population in the north quarter is furnished by the fact that south of Cheapside there were more than twice as many churches as in the north.

Now, when these people began to cluster together, which was long before the Norman Conquest, in fact, soon after Alfred’s settlement, they built their cottages each to please himself. Thus it was that one house faced the east, another the south, another the north-west. The winding ways were not required for carts or vehicles, which could not be used in these narrow lanes; only for a means of communication by which the things the craftsmen made might be carried to Cheapside or Eastcheap or wherever their productions were exposed for sale. On the north side of Cheapside, therefore, London presented the appearance of a cluster of villages with their parish churches. Each village contained the craftsmen of some trade or mystery. Perhaps the same parish church served for two or more such villages. This part of London was extremely picturesque, according to our ideas. The parish churches were small, and, as I have already said, mostly built of wood; around them were the houses and workshops of the craftsmen; the green churchyard lay about the church; on the north between the houses and the wall were orchards and gardens. The lane from the village to West or East Chepe lay between the houses, winding and turning, sometimes narrow, sometimes broad; the prentices carried the wares, as they were made, to the market, where they were exposed for sale all day; from every one of these villages, from six in the morning till eight in the evening, the sounds of labour were heard: the clang of the hammer on the anvil, the roar of the furnace, the grating of the saw, and the multitudinous tapping, beating, and banging of work and industry; it was a busy and industrious place, where everything was made in the City that was wanted by the City.

325

We shall have to consider the gilds or guilds in connection with the rise of the Companies separately. It must be remembered, however, that guilds were already in existence, and that there were many of them. (See Mediæval London, vol. ii. p. 108.)

We have been speaking of the northern quarter of London. Let us turn next to that part which lay south of Cheapside. The removal of the river wall followed, but gradually, the reclaiming of the foreshore along the north bank.

LONDON WALL

LONDON WALL

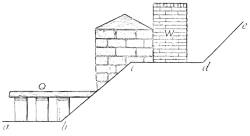

We have seen how the first ports of London—Walbrook and Billingsgate—were constructed. The former, a natural harbour but very small, was protected by towers or bastions on either side, and was provided with quays, resting on piles driven into the mud. The latter was simply cut out of the mud and shingle, kept in shape by piles driven close together and provided with quays laid upon the piles. As trade increased the quays increased, not only laterally, but by being advanced farther out into the foreshore. Consider that the process was going on continually, that not only did the quays extend, but that warehouses and houses of all kinds were built upon the sloping bank. The section shows what was going on. The quay (Q) resting on piles driven into the bed of the river (ab), in front of the sloping bank (bc); the warehouse erected behind it, resting against the wall: the level space (cd) cleared for the wall (W), where is now Thames Street: the low hill behind (de). The wall was in the way: without authority, without order, the people pierced it with posterns leading to quays and stairs; without authority they gradually pulled it down.

It is impossible to say when this demolition began; the river wall was standing in the time of Cnut: it appears no more. When Queen Hythe (Edred’s Hythe) was constructed, in size and shape like the port of Billingsgate, either a postern had to be made for it, or a postern already existed.

The reclaiming of the foreshore (see p. 125) was a very important addition to the area of London: it added a slip of ground 2200 yards in length by an average of 100 yards in breadth, i.e. about forty-five acres of ground, which was presently covered with narrow lanes between warehouses. The lanes, many of which remain and are curious places to visit, led to river stairs, and were the residences of the people employed in the service of the port.

As for the removal of the wall, exactly the same process was followed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the people began gradually to take down the City wall; they built against it, before it, and behind it; and, no one interfered.

326

The lower part of the town was by far the more crowded: if we take a map of London and count the churches immediately north and south of Cheapside and Cornhill, this fact comes home to us very clearly. Thus, there are north of that boundary, thirty-one; south of the boundary there are sixty-eight, counting roughly. The lower part of the town contained the wharves and the warehouses, the lodgings of the people employed in the work of loading and unloading the ships, the taverns and the places of refreshment for the sailors and such persons; the narrow lanes and the absence of any historical houses in the part south of Thames Street show that the place, after the reclaiming of the foreshore, was always what it is now, either a place for warehouses or for the residence of the service. A great many of the merchants lived on the rising ground north of Thames Street. Hence we find here a great many Companies’ Halls: here Whittington, later on, had his lordly house in which he interviewed kings; here, in the time we are considering, such Norman nobles and knights as had houses in the City all lived. Thus in Elbow Lane lived Pont de l’Arche, second founder of St. Mary Overies. The Earls of Arundel had a house in Botolph Lane, Billingsgate; Lord Beaumont—but this was later—lived beside Paul’s Wharf; Henry FitzAylwin, first Mayor of London, lived close beside London Stone.

I do not suppose that any of the houses in Norman London could compare with the palaces erected by the merchants of the fourteenth century,—there was no such place as Crosby Hall among them; but still they were good and stately houses. There was a large hall in which the whole family lived: the fire was made in a fire-place with open bars; the smoke ascended to the roof, where it found a way out by the lantern; the windows were perhaps glazed; certainly glass merchants appeared in the country in the eleventh century; if they were not glazed they were covered with a white cloth which admitted light; the two meals of the day were served on tables consisting of boards laid on trestles; the servants all slept on the floor on the rushes, each with a log of wood for a pillow, and wrapped in his blanket; the master of the house had one or more bedrooms over the kitchen called the Solar, where he slept in beds, he and his wife and family. At the other end of the hall was a room called the Ladies’ Bower, where the ladies of the house sat in the daytime with the maids. If you want to see an admirable specimen of the mediæval house with the Hall, the Solar, and the Bower, all complete, you may see it at Stokesay Castle, near Ludlow.

In the craftsmen’s cottages the people seem to have all slept on straw. In the fourteenth century, however, we find the craftsmen amply provided with blankets, pillows, and feather-beds.

We can, in fact, at this period, divide the City into parallel belts, according to the character and calling of the residents. Everything to do with the export, import, and wholesale trade was conducted in Thames Street, and on its wharves:327 the porters, stevedores, servants, and sailors lived in the narrow lanes about Puddle Dock at one end of Thames Street, and Tower Hill at the other. That is the first belt—the belt of the port. The rising ground on the north was the residence of the merchants and the better sort. That is the second belt. Next comes the breadth of land bounded by Watling Street and Eastcheap on the south, and by an imaginary line a little north of Cheapside on the north, this was mainly given over to retail trade, and it is the third belt. My theory is illustrated by the names. Thus I find in this retail belt all the names of streets indicating markets, not factories.

The fourth belt is that quarter where the industries were carried on: namely, the large part of the City lying north of Cheapside and Cornhill. Let me repeat that London was a hive of industries: I have counted belonging to the fourteenth century as many as 284 crafts mentioned in the books; and of course there must have been many others not mentioned.

I have called attention to the fact that in the eleventh century there was but one Religious House in the City of London. Considering the great number which sprang up in the next hundred years, this seems remarkable. Let us, however, remind ourselves of an important feature in the history of religion and of Religious Houses in this country. I mean the successive waves of religious enthusiasm which from time to time have passed over our people. In the eighth century there fell upon Saxon England one of these waves—a most curious and unexampled wave—of religious excitement. There appeared, over the whole country, just the328 same spirit of emotional religion which happens at an American camp-meeting or a Salvation Army assembly,—men and women, including kings and queens, earls and princesses, noble thanes and ladies, were alike seized with the idea that the only way to escape from the wrath to come was by way of the monastic life; they therefore crowded into the Religious Houses, and filled them all. After the long struggle with the Danes, for two hundred years there was no more enthusiasm for the religious life, for all the men were wanted for the army, and all the women were wanted to become mothers of more fighting men.

The coldness with which the religious life was viewed by the Londoners was therefore caused by the absolute necessity of fighting for their existence. One Religious House, and that not a monastery but a college, was enough for them: they wanted no more. But London was never irreligious; there was as yet no hatred of Church or priest; there was as yet no suspicion or distrust as to the doctrines taught by Mother Church. For three hundred years the citizens felt no call to the monastic life. In the reign of Henry the First a second wave of religion, of which I have already spoken twice, fell upon the people, and especially the people of London. It was the same wave that drove the French to the Crusades. Under the influence of this new enthusiasm, founders of Religious Houses sprang up in all directions. Already in 1086, Aylwin, a merchant of London, had founded St. Saviour’s Abbey, in Bermondsey. In Bermondsey Abbey it was intended to create a foundation exactly resembling that of St. Peter’s, Westminster. Like the latter House, Bermondsey Abbey was established upon a low-lying islet among the reeds of a broad marsh near the river. The House was destined to have a long and an interesting history, but to be in no way the rival, or the sister, of Westminster. Another Religious House was that of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and Priory, founded by Rahere, variously stated to have been a jester, a minstrel, a man of mean extraction, and a man of knightly parentage. His origin matters nothing; yet his Foundation exists still, and still confers every year the benefits of an hospital upon thousands of those who suffer and are sick. (See Mediæval London, vol. ii. p. 250.)

Every one knows the Church of St. Mary Overies, commonly called the Church of St. Saviour, across the river. That church belonged to the Religious House founded, or rebuilt and magnified, by two Norman knights. We have spoken of St. Giles in the Fields already. There was a Nunnery founded at Clerkenwell about the year 1100; there was also a House of St. John (see Mediæval London, vol. ii. p. 270). The last of the Houses due to this religious revival is the Priory of the Holy Trinity, Aldgate. This was founded by one Norman as a House of Augustinian Canons. The Queen, Henry the First’s Saxon Queen, Matilda, endowed it with land and with the revenues of Aldgate. It must be acknowledged that this religious revival was both of long continuance and of real depth, since so many were seized329 by it and moved either to found Houses of Religion, or to take upon them the vows of religion.

There is one more illustration of this religious revival of the twelfth century. This is the Cnihten Gild or Guild. One writer would see in this guild the lost Merchant Guild of the City, of which I have already spoken (see Mediæval London, vol. ii. p. 113), and in the action of the leaders the destruction of the Merchant Guild. Others would see in it a Guild for the defence of the City. I confess that I cannot understand why the Merchant Guild of the whole City should be destroyed by the action of fifteen leaders, nor how a commercial association for the good of all could be broken up by a few of its more important members. It would be also very difficult to make out that this Cnihten Gild did in any sense correspond to the Merchant Guild; and I would ask what a Merchant Guild had to do with fighting? Yet Stow undoubtedly preserves a tradition of battle about the Cnihten Gild. The theory that there was a Company or Guild whose duty it was to organise the defence of the City, to be the officers of a Militia containing every able-bodied man within the walls, seems to account for330 everything. Now this body of citizen soldiers had already six times beaten off the Danes; they therefore possessed an honourable record. When William took possession he was careful to disturb nothing; therefore he did not disturb the Cnihten Gild. If the object of their existence, however, was the defence of the City, they had nothing more to do; for when William built the White Tower in the east and Montfichet in the west, he said to the citizen soldiers, practically, “I will take care of your defence; your work is done.”

This may be theory and imagination. To me it seems to account for the Cnihten Gild more naturally than the supposition of a Merchant Guild. For one does understand the coming of a time when it was no longer necessary to have such a Guild of defence; but one does not understand how any time, or any combination of circumstances, would make it necessary, or even permissible, for the leaders to surrender or to destroy the Merchant Guild, which regulated the whole trade of the City and was above and before all other Guilds.

The facts of the case are as follows: their meaning and importance have been misunderstood until they were explained by Mr. J. H. Round. In the year 1881, however, a paper on the subject was read before the London and Middlesex Archæological Society by Mr. H. C. Coote. They are, briefly, as follows:—

The land which now forms the Ward of Portsoken, i.e. the “Soc” or “Socn” of the City, was in the hands of a certain body known as the Cnihten Gild. There were fifteen of them whose names have been preserved. They were Raulf, son of Algod; Wulward le Doverisshe; Orgar le Prude; Edward Upcornhill; Blackstan, and Alwyn his cousin; Ailwin, and Robert his brother, sons of Leofstan; another Leofstan, the Goldsmith, and Wyzo his son; Hugh, son of Wulgar; Orgar, son of Dereman; Algar Fecusenne; Osbert Drinchewyn, and Adelard Hornewitesume. These men, all London citizens of position, held the lands on trust as members of the Gild.

It was called the Cnihten Gild: the Soldiers’ Guild. They possessed, among other things, a Charter of King Edward the Confessor. It ran as follows:—

“Eadward the King greeteth Ælfward the bishop and Wulfgar the portreeve and all the burgesses of London as a friend. And I make known to you that I will that my men in the English Gild of Knights retain their manorial rights within the city and without over their men; and I will that they retain the good laws (i.e. the privileges) which they had in King Eadgar’s day and in my father’s and Cnut’s day; and I will also (?)27 with God and also man and I will not permit that any man wrong them but they shall all be in peace and God preserve you all.”

There had been Charters, therefore, of Edgar, Ethelred, and Cnut. The Charter of Edward presupposes the existence of the Gild in the time of Edgar. Now, under the Saxon customs a Gild was legally constituted when the members331 created it; the consent of the King was an invention of Norman times. Yet it seems probable that the Gild was first founded in the reign of Edgar for reasons advanced by Coote.

“Immediately before that King’s accession to the throne there had arisen a very cogent necessity for the City to look out for increased protection—for some regular and settled means which should ensure her citizens against sudden and stealthy attacks during that chronic warfare to which the age had been for some time tending. There had been a civil war caused by the disgust of a part of the nation at King Eadwig’s unparallelled profligacy, and in that war, as it is expressly stated by historians, the outskirts of London had suffered much. During its pendency there had been fighting and devastation on both sides of the Thames in the immediate vicinity of the City.”

The Cnihten Gild, therefore, appears to have been an association founded for the purpose of providing for every occasion a permanent standing garrison of defence. The ruling body contained a certain number of leading London citizens: they were the officers of the Gild. They administered the funds and property belonging to the Gild, and were useful in repairing the wall and gates, and in providing arms. It was only by means of the Gild, in which the members were under oath of obedience, that such a garrison could be got together and maintained. How many members the Gild at first contained is not known. It is, however, probable that by the year 1125, when the fifteen named above are described as “of the ancient stock of noble English soldiers,” the Gild had become a small survival still owning property; though, as we have seem, they could have had no duties to perform.

William, however, recognised the existence of the Gild and granted them a Charter. This is lost, but the Charter of William Rufus, which remains, refers to it.

“William, King of England, to Bishop M. and G. de Magnaville and R. Delpare and his lieges of London, Greeting. Know ye that I have granted to the men of the cnihtene gild their gild and the land which belong to them, with all customs, as they were in the time of King Edward and my father. Witness, Henry de Both, at Rethyng.”

And Henry I. also granted them a Charter in which he refers to those of his father and his brother:—

“Henry, King of England, to Bishop M., to the gerefa of London, and to all his Barons and lieges of London, French and English, Greeting. Know ye that I have granted to all the men of the cnihtene gild their gild and land which belong to them, with all customs, as were better in the time of King Edward and my father, and as my brother granted to them by writ and his seal, and I forbid upon pain of forfeiture to me that any man dare do them an injury in respect of this. Witness, R. de Mountford and R. Bigot and H. de Booth, at Westminster.” (London and Middlesex, 1881, vol. v. p. 488.)

332

Sixty years after the Conquest, the Gild, realising that the original reason for their association no longer remained in existence, proposed to dissolve. What were they to do with the property for which they were trustees? It was the property of the City: it had to be used for the benefit of the City. What better, according to the light of the time, could they do with it than hand it over to the Church and to ask for the prayers of holy men? Accordingly they asked permission of the King to convey the property to the Priory of the Holy Trinity. His consent was obtained. The King appointed as Commissioners for the conveyance Aubrey de Vere (who was afterwards killed in a street riot) and Gervase of Cornhill, and the document was signed by the members of the Gild whose names have been already set forth.

The following document is quoted by Mr. Coote from the records of the Hustings Court at Guildhall:—

333

“Anno ab incarnacione domini Millesimo centissimo octauo et Anno regni gloriosi Regis Henrici octauo fundata est ecclesia Sancte Trinitatis infra Algate Londoñ per venerabilem Reginam Matildam uxorem Regis predicti, et Consilio sancti Archipresulis Anselmi data est dicta ecclesia Normanno Priori primo tocius regni Canonico. A quo tota Anglia Sancti Augustini Regula ornatur et habitu canonicali vestitur et congregatis ibidem fratribus augebatur in dicta ecclesia multitudo laudancium deum die ac nocte ita quod tota ciuitas delectabatur in aspectu eorum. In tantum quod anno ab incarnacione domini millesimo centesimo vicesimo quinto quidam burgenses Londonie ex illa antiqua nobilium militum Anglorum progenie, scilicet Radulfus filius Algodi Wulwardus le Doverisshe, Orgarus le Prude, Edwardus Upcornhill, Blackstanus et Alwynus cognatus eius, Ailwinus et Robertus fratur eius filii Leostani, Leostanus Aurifaber, et Wyzo filius eius, Hugo filius Wulgari, Algarus fecusenne (sic) Orgarus filius Deremanni, Osbertus Drinchewyn, Adelardus Hornewitesume (sic) conuenientes in capitulo ecclesie Christi que sita est infra muros eiusdem ciuitatis iuxta portam que nuncupatur Algata dederunt ipsi ecclesie et canonicis Deo seruientibus in ea totam terram et socam que dicebatur de Anglissh Cnithegilda urbis que muro adiacet foras eandem portam et protenditur usque in fluuium Thamesiam. Dederunt inquam suscipientes fraternitatem et participium beneficiorum loci illius per manum Normanni Prioris qui eos et predecessores suos in societatem super textum evangelii recepit. Et ut firma et inconutta (sic for inconcussa) staret hec eorum donacio cartam sancti Edwardi cum aliis cartis prescriptis quas inde habebant super altare optulerunt. Et deinde super ipsam terram seisiuerunt predictum priorem per ecclesiam sancti Botulphi que edificata est super eam et est ut aiunt capud ipsius terre. Hec omnia facta sunt coram hiis testibus Bernardo Priore de Dunstap’l, etc. etc. Miserunt ergo predicti donatores quendam exseipsis, Ordgarum scilicet le Prude, ad regem Henricum petentes ut ipse donacionem eorum concederet et confirmaret. Rex vero libenter concessit predictam socam et terram prefate ecclesie liberam et quietam ab omni servicio sicut elemosinam decet et cartam suam sequentem confirmauit.” (London and Middlesex, 1881, vol. v. pp. 477-478.)

The “soc” thus transferred was the right to administer justice, civil or criminal, to, and in respect of, the men or under-tenants of the Gild. The right, therefore, belonged henceforth to the Prior of the Convent who, when Portsoken became a Ward, was, ex officio, Alderman of that Ward.

It is very remarkable that writers on this conveyance have always, down to Mr. Round, assumed that the fifteen who constituted the Gild entered the Priory and assumed the vows of the Order.

The Latin words are, however, quite clear. I repeat them: “Dederunt, inquam, suscipientes fraternitatem et participium beneficiorum loci illius per manum Normanni Prioris qui eos et predecessores suos in societatem super textum evangelii recepit.”

That is:—

“Taking up the fraternity and share in the benefits of that place by the hand of Norman the Prior, who received them and their predecessors into the Society on the text of the Gospels.”

There was attached to every monastery a fraternity whose numbers were not limited: their duties were not defined: probably there were no duties except attendance once a year or so, and gifts to the House according to the power and means of the giver. At the hour of death the members put on the robe of the Order. The Gild, therefore, entered the Fraternity and obtained, by their gift of this land, all the benefits that the Fraternity would claim from its connection with the House for themselves and their predecessors.

Their predecessors could not enter the House; nor could they, since they were on exactly the same footing as their predecessors.

Round illustrates the point by a note:—

334

“Good instances in point are found in the Ramsey Cartulary where, in 1081, a benefactor to the abbey ‘suscepit e contra a domino abbate et ab omnibus fratribus plenam fraternitatem pro rēge Willelmo, et pro regina Matilda, et pro comite Roberto, et pro semetipso, et uxore sua, et filio qui ejus erit heres, et pro patre et matre ejus, ut sunt participes orationum, elemosinarum, et omnium beneficiorum ipsorum, sed et omnium fratrum sive monasteriorum a quibus societatem susceperunt in omnibus sicut ex ipsis.’ Better still is this parallel: ‘Reynaldus abbas, et totus fratrum conventus de Rameseya cunctis fratribus qui sunt apud Ferefeld in gilda, salutem in Christo. Volumus ut sciatis quod vobis nostram fraternitatem concessimus et communionem beneficii quam pro nobismet ipsis quotidie agimus, per Serlonem, qui vester fuit legatus ad nos, ut sitis participes in hoc et in futuro saeculo.’ The date of this transaction was about the same as that of the admission of the Cnihten Gild to a share in the ‘benefits’ of Holy Trinity; and the grant was similarly made in return for an endowment.” (The Commune of London.)

But he proves the point still more clearly when he traces the subsequent history of the fifteen for many years after the conveyance in act and deed outside the Priory.

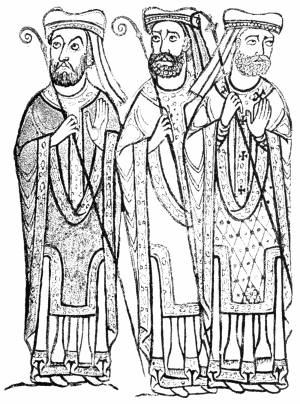

The marriage of priests was a burning subject of the day. Practically, priests in England were as much married then as the Anglican clergy are now; they married, as will be shown presently, into families of good position, and occupied much the same position as they do at present. But it was resolved at Rome that celibacy should be enforced among the clergy. The evidence of the Chronicles is somewhat conflicting. There were two important Synods on ecclesiastical affairs—the first held in 1102, and the second in 1108. The celibacy of the clergy appears to the historian a smaller matter than the investiture of any ecclesiastical dignity by the hand of a layman.

Florence of Worcester (circa 1118) mentions the Synod of 1102, and says nothing about the question of celibacy, but refers the decrees on the subject to the year 1108. He also gives in full seventeen canons passed at the Synod of 1125 held at Westminster, by John de Cremona. He says nothing about the Cardinal’s confusion and shame. He also quotes the decrees of the Synod of 1127.

Henry of Huntingdon (circa 1154) says:—

“At the feast of St. Michael, the same year—1102—Anselm, the archbishop, held a synod at London, in which he prohibited the English priests from living with concubines, a thing not before forbidden. Some thought it would greatly promote purity; while others saw the danger in a strictness which, requiring a continence above their strength, might lead them to fall into horrible uncleanness, to the great disgrace of their Christian profession. In this synod several abbots, who had acquired their preferment by means contrary to the will of God, lost them by a sentence conformable to his will.”

And under the year 1125, he describes the visit of John de Cremona, with the discovery which brought his mission to a hurried conclusion.

“At Easter, John of Cremona, Cardinal of Rome, came into England, and visited all the bishoprics and abbeys, not without having many gifts made him.”

“This Cardinal, who in the council bitterly inveighed against the concubines of priests, saying that it was a great scandal that they should rise from the side of a harlot to make Christ’s body, was the same night surprised in company with a prostitute, though he had that very day consecrated the host. The fact was so notorious that it could not be denied, and it is not proper that it should be concealed. The high honour with which the cardinal had been everywhere received was now converted to disgrace, and, by the judgment of God, he turned his steps homewards in confusion and dishonour.”

335

Roger of Wendover (d. 1256) says that in 1102 Anselm excommunicated priests who had concubines. He says that the Council of 1108 was occupied with the question of investiture. As to the affair of 1125, he simply copies Henry of Huntingdon.

Matthew of Westminster (circa 1320) says that in 1102 Anselm, at a Synod held in St. Paul’s, excommunicated priests who kept concubines—or, in plain words, were married.

The Synod of 1108, he says, was occupied by the question of investiture. About the Cardinal, John of Cremona, he merely says:—

“The said John, who in the council had most especially condemned all priests who kept concubines, being detected himself in the same vice, excused the vice because he said that he was not himself a priest, but a reprover of priests.”

The three strenuous efforts made in 1102, 1108, and in 1125, show the importance attached to the question of priests’ marriages by the Church of Rome.

The deans of 1102, the canons of 1125, and the statutes of 1127 are a revelation of the abuses which were then prevalent in the Church. It would be interesting to compare these ordinances with the condition of the Church in the following centuries. The canons (see Appendix) declared the whole of the Church offices except marriage, viz., chrism, oil, baptism, penance, visitation of the sick, Holy Communion and burial, open to all without fee; they forbade the inheritance of Church patronage; they ordered clerks holding benefices to be ordained priests without delay; that the office of Dean or Prior should be held by a priest; and that of Archdeacon by a deacon at least; that the Bishop alone should have the power of ejecting any person from a benefice; that an excommunicated person should not receive communion from any; that pluralists should be made illegal; that priests should have no women in their houses except such as were free from suspicion; that marriage should be prohibited; that sorcerers should be excommunicated; that priests who kept their concubines should be deprived of their benefice; that the concubines should be expelled the parish; that priests should not hold farms; that tithes be paid honestly; that no abbess or nun was to wear garments more costly than lamb’s wool or cat’s skin.

These regulations were stringent in the highest degree. Nevertheless they appear to have been totally disregarded. A hundred years later, when the Interdict was laid upon England, we find that the priests’ concubines throughout the country had to pay ransom.

For the priests did not give up their wives: they continued to marry; they also continued to present their sons to benefices. In a word, the law became, like most of the mediæval laws, ineffectual, because there was no means of enforcing it and the opinion of the people was against it. On the one hand, there was the danger of the priesthood becoming an hereditary caste, and of benefices descending as by right336 from father to son—a danger which the subsequent history of the Anglican Church shows to have been imaginary or exaggerated; on the other hand, there were the great dangers resulting from the enforced suppression of the most powerful passion, the most overwhelming of all passions, in some men simply irresistible, by denying the natural custom of wedlock. And as history abundantly proves, these dangers were not imaginary.

As to the quarrel between Henry and Anselm, that belongs to the history of the country rather than to that of London.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content