Search london history from Roman times to modern day

289

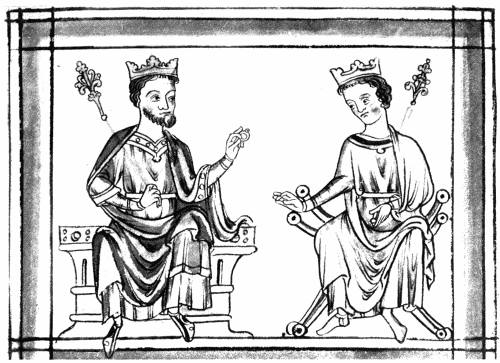

The election of Stephen by London is a fact the full importance of which, in the history of the City, was first brought out by the late J. R. Green. This importance signified, in fact, a great deal more than the election of a king by the City of London, a thing by no means new in the history of the City. First, we know that many Normans flocked over to London after the Conquest. Normans there were before that event, but their numbers rapidly increased in consequence. By this time we see that the immigrants no longer considered themselves Normans only, but Londoners as well. William’s Charter especially recognises and provides for this fusion when he “greets all the burgesses in London, Frenchmen and Englishmen, friendly.” The Normans were his subjects as well as the English: they were not, therefore, aliens in his English cities. For instance, Gilbert Becket, father of the Archbishop, was by birth a burgher of Rouen, and his wife was the daughter of a burgher of Caen. But his son Thomas was always an Englishman. The Normans in London, therefore, took their part without question in the election of a king of England. And they elected Stephen rather than Henry, the son of the Empress, because Henry was also the son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, and the hatred of Norman for Angevin was greater even than the hatred of Welshman for Englishman. It survived the immigration of the Norman into England; it found expression when King Henry died, and when his stepson Geoffrey of Anjou seemed likely to claim the throne of England, as he claimed the duchy of Normandy, in right of his wife. In Normandy, however, the people rose as one man, and chased him out of the dukedom. In London, the City seems to have assumed the power of electing the King of England, as in the case of Henry, and without consulting bishop, abbot, or noble, did elect Stephen, the nephew of King Henry, and crowned him in Westminster. There were, in fact, two forces working for Stephen. The first was this said Norman jealousy of Anjou. The second was perhaps stronger. The religious revival of which we spoke as belonging to the reign of Henry, was spreading over the whole of western Europe. Green calls it the first of the great religious movements which England was to experience. He seems to forget, however, that there was a much earlier religious movement, which filled290 the monasteries and weakened the country, by draining it of fighting-men, in the eighth century.

“Everywhere in town and country men banded themselves together for prayer, hermits flocked to the woods, noble and churl welcomed the austere Cistercians as they spread over the moors and forests of the North. A new spirit of enthusiastic devotion woke the slumber of the older orders, and penetrated alike to the home of the noble Walter d’Espec at Rievaulx, or of the trader Gilbert Becket in Cheapside. It is easy to be blinded in revolutionary times, such as those of Stephen, by the superficial aspects of the day; but, amidst the wars of the Succession, and the clash of arms, the real thought of England was busy with deeper things. We see the force of the movement in the new class of ecclesiastics that it forces on the stage. The worldliness that had been no scandal in Roger of Salisbury becomes a scandal in Henry of Winchester. The new men, Thurstan, and Ailred, and Theobald, and John of Salisbury—even Thomas himself—derive whatever weight they possess from sheer holiness of life or aim.”—Historical Studies.

The outward sign of this movement was the foundation of many religious houses, and the building of many churches. The number and importance of the foundations created in or about London, not taking into account those founded in the country, within a space of about twenty years, indicate in themselves a widespread, deep-rooted, religious feeling. It was an age of fervent faith; Stephen himself, rough soldier that he was, felt its influence.

Now this religious fervour was openly scorned and scoffed at and derided by the Angevins. Contempt for religion was hereditary with them. From father to son they gloried in deriding holy things. In the words of Green: “A lurid grandeur of evil, a cynical defiance of religious opinion, hung alike round Fulc Nerra, or Fulc Rechin, or Geoffrey Plantagenet. The murder of a priest by Henry Fitz-Empress, the brutal sarcasms of Richard, the embassy of John to the Moslems of Spain, were but the continuance of a series of outrages on the religious feelings of the age which had begun long ere the lords of Anjou became Kings of England.”

To the reasons why the City had taken upon itself to elect and to crown Stephen, viz. the Norman hatred of Anjou, and resentment against the man of no religion, must be added two more: the conviction that a strong armed man, and not a woman, was wanted for the country; and a general restlessness which, the moment the old king was dead, broke out everywhere in acts of lawlessness and robbery.

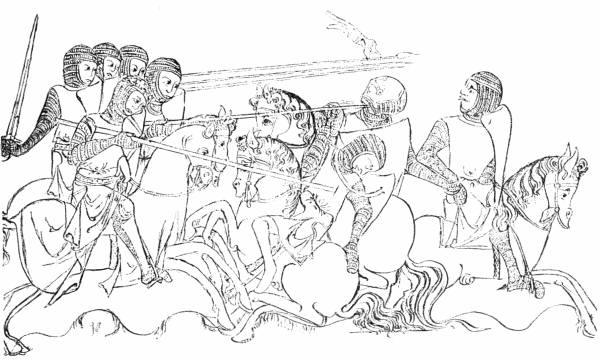

It was not yet a time when peace was possible, save at intervals; the barons and their following must needs be fighting, if not with the common enemy, then with each other. The burghers of London, as well as the barons, felt frequent attacks of those inward prickings which caused the fingers to close round the hilt and to draw the sword. Historians have not, perhaps, attached enough importance to the mediæval—is it only mediæval?—yearning for a fight. There is nothing said about it in any of the Chronicles, yet one recognises its recurrence. One feels it in the air. Only a strong king could keep down the fighting spirit, or make it find satisfaction and outlet in local brawls.

Never in this country, before or after, was there such an opportunity for291 gratifying this passion to be up and cutting throats. Historians, who were ecclesiastics, and therefore able to feel for and speak of the sufferings of the people, write of the horrors of war. The fighting-men themselves felt none of the horrors. Though the country-people starved, the men of war were well fed; though merchants were robbed and murdered, the men of war were not hanged for the crime; to die on the battlefield, even to die lingering with horrible wounds, had no terrors for these soldiers; nay, this kind of death seemed to them a far nobler lot than to die in a peaceful bed like a burgher. Dead bodies lay in heaps where there had been a village—dead bodies of men, women, and children, which corrupted the air. The shrieks of tortured men rang from the castles, and the despairing cries of outraged maidens from the farmhouse. The towns were laid in ruins, the cultivated lands were laid desolate, the country was deserted by the people, yet these things were not horrors to the men of war, they were daily sights. For nearly twenty years the battlefield was the universal death-bed of the Englishman; and since harvests were burned, cattle destroyed, rustics murdered, priests and merchants robbed, one wonders how, at the end of it, any one at all was left alive in England. As for the City of London, it paid dearly for the choice of a king; and in the long run it had to see the other side, the House of Anjou, come to reign over its people.

Henry died on the 1st of December 1135. Twenty-four days afterwards, Stephen received the crown from the hands of the Archbishop. During the interval the country had become, suddenly, a seething mass of anarchy and violence. A strong292 hand had held it down for more than thirty years—a period, one would think, long enough for a spirit of obedience to law and order to grow up in men’s minds. Not yet: the only obedience was that due to fear; the only respect for law was that inspired by the hardest and most inflexible of kings. The words used by the author of the Gesta Stephani were doubtless much exaggerated, but they point to an outbreak of lawlessness which was certainly made possible by the removal of Henry’s mailed hand.

“Seized with a new fury, they began to run riot against each other; and the more a man injured the innocent, the higher he thought of himself. The sanctions of the law, which form the restraint of a rude population, were totally disregarded and set at naught; and men, giving the reins to all iniquity, plunged without hesitation into whatever crimes their inclinations prompted.... The people also turned to plundering each other without mercy, contriving schemes of craft and bloodshed against their neighbours; as it was said by the prophet, ‘Man rose up without mercy against man, and every one was set against his neighbour.’ For whatever the evil passions suggested in peaceable times, now that the opportunity of vengeance presented itself, was quickly executed. Secret grudgings burst forth, and dissembled malice was brought to light and openly avowed.” (Henry of Huntingdon.)

Then Stephen, crossing over from Ouissant (Ushant) with a fair wind, landed at Dover, and made haste to march to London, where he counted upon finding friends. His succession, indeed, was no new thing suddenly proposed; there had been grave discussions, prompted by the considerations above detailed, as to adopting Stephen as the successor. In addition to his reputation as a soldier, Stephen possessed the charm of personal attraction and generosity.

The City, however, as in the case of William the Conqueror and his son Henry, elected Stephen king after a solemn Covenant that, “So long as he lived, the citizens should aid him by their wealth and support him by their arms, and that he should bend all his energies to the pacification of the kingdom.”

Round (see below) discusses this covenant and the assertion in the Gesta that the Londoners claimed the right of electing the king. He compares the oath taken by king or overlord at certain towns in France, such as Bazas in Aquitaine, Issigeac in the Perigord, Bourg sur Mer in Gascony, and Bayonne. At all these places the oath was practically in the same form: the citizens swore obedience and fidelity to the king, while the king in return swore to be a good lord over them, to respect and preserve their customs, and to guard them from all injury. This oath was, in fact, William the Conqueror’s Charter. It was probably neither more nor less than this which the citizens of London exacted from Stephen. Six years later it was the same oath which they exacted from the Empress. Now, as the French towns referred to did not speak or act in the name of the whole kingdom or the province, may not the action of London in 1135 have been, not so much to assert their right to elect the293 king, as their resolution to make their recognition of a successor to the throne, when the succession was disputed, the subject of a separate negotiation?

At the first Easter after his coronation, Stephen held his Court at Westminster, where he assembled a National Council, to which were bidden the Bishops and Abbots and the Barons, “cum primis populi.” The Easter celebrations had been gloomy of late years, owing to the sadness which weighed down Henry after the death of his son. This function revived the memory of former splendours—“quâ nunquam fuerat splendidior vestibus.” That this Council was attended by the greatest barons of the realm, is proved by the fact that two Charters there granted are witnessed, one by fifty-five, and the other by thirty-six men, including thirty-four noblemen of the highest rank.

Geoffrey de Mandeville by Mr. J. H. Round is much more than a biography: it is a scholarly—a profound—inquiry into the history of England, and especially London, under King Stephen.

Geoffrey de Mandeville was the son of William de Mandeville, who was Constable of the Tower in 1101; and the grandson of Geoffrey de Mandeville, who appears to have come from the village of Mandeville near Trevières in the Bessin, the name being Latinised into “De Magna villâ.”

The elder Geoffrey founded a Benedictine priory at Hurley.

The younger Geoffrey appears at Stephen’s Court in 1136 as a witness to certain deeds. He was created Earl of Essex in 1140: the date being fixed by Round.

But the Empress was already in England: in 1141 (February 2) her great victory at Lincoln placed her for the time in command of the situation, and made Stephen a prisoner. She repaired to Winchester, where (March 2, 1141) she was elected “Domina Angliae.” She was received by the Legate, the clergy, and the people, the monks and nuns of the religious houses. She also took over the castle, with the crown and the royal treasures.

What follows is a remarkable illustration of the power of London. It is thus described by Sharpe (London and the Kingdom, vol. i. p. 48):—

294

“But there was another element to be considered before Matilda’s new title could be assured. What would the Londoners, who had taken the initiative in setting Stephen on the throne, and still owed to him their allegiance, say to it? The Legate had foreseen the difficulty that might arise if the citizens, whom he described as very princes of the realm by reason of the greatness of their City (qui sunt quasi optimates pro magnitudine civitatis in Angliâ), could not be won over. He had therefore sent a special safe conduct for their attendance, so he informed the meeting after the applause which followed his speech had died away, and he expected them to arrive on the following day. If they pleased they would adjourn till then. The next day (April 9) the Londoners arrived, as the Legate had foretold, and were ushered before the Council. They had been sent, they said, by the so-called ‘commune’ of London; and their purpose was not to enter into debate, but only to beg for the release of their lord the King. This statement was supported by all the barons then present who had entered the commune of the City, and met with the approval of the archbishop and all the clergy in attendance. Their solicitations, however, proved of no avail. The Legate replied with the same arguments he had used the day before, adding that it ill became the Londoners, who were regarded as nobles (quasi proceres) in the land, to foster those who had basely deserted their King on the field of battle, and who only curried favour with the citizens in order to fleece them of their money. Here an interruption took place. A messenger presented to the Legate a paper from Stephen’s Queen to read to the Council. Henry took the paper, and after scanning its contents, refused to communicate them to the meeting. The messenger, however, not to be thus foiled, himself made known the contents of the paper. These were, in effect, an exhortation by the Queen to the clergy, and more especially to the Legate himself, to restore Stephen to liberty. The Legate, however, returned the same answer as before, and the meeting broke up, the Londoners promising to communicate the decision of the Council to their brethren at home, and to do their best to obtain their support.”

The negotiations dragged on. There are clear indications of tumults and dissensions in the City: Geoffrey de Mandeville strengthened the Tower; Aubrey de Vere, his father-in-law, formerly Sheriff and Royal Chamberlain to Henry I., was slain in the streets; the Norman party were not likely to yield without a struggle. However, in June 1141, a deputation of citizens was sent to the Empress, who waited for them at St. Albans. She made one promise, presumably the same made by William her grandfather, by Henry her father, and by Stephen, that she would respect the rights and privileges of the City; she was then formally received by the notables, who rode out to meet her, according to custom, at Knightsbridge.

295

“Having now obtained26 the submission of the greatest part of the kingdom, taken hostages and received homage, and being, as I have just said, elated to the highest pitch of arrogance, she came with vast military display to London, at the humble request of the citizens. They fancied that they had now arrived at happy days, when peace and tranquillity would prevail.... She, however, sent for some of the more wealthy, and demanded of them, not with gentle courtesy, but in an imperious tone, an immense sum of money. Upon this they made complaints that their former wealth had been diminished by the troubled state of the kingdom, that they had liberally contributed to the relief of the indigent against the severe famine which was impending, and that they had subsidised the King to their last farthing: they therefore humbly implored her clemency that in pity for their losses and distresses she would show some moderation in levying money from them.... When the citizens had addressed her in this manner, she, without any of the gentleness of her sex, broke out into insufferable rage, while she replied to them with a stern eye and frowning brow, ‘that the Londoners had often paid large sums to the King; that they had opened their purse-strings wide to strengthen him and weaken her; that they had been long in confederacy with her enemies for her injury; and that they had no claim to be spared, and to have the smallest part of the fine remitted.’ On hearing this, the citizens departed to their homes, sorrowful and unsatisfied.”

The Empress came to London because she desired above all things to be crowned at Westminster. This was impossible, or useless, without the previous submission of London, and she did not gain her desire. It is readily understood that there were malcontents enough in the City. Her imperious bearing increased the number. Moreover, at this juncture, Stephen’s Queen, Maud, arrived at Southwark with a large army and began, not only to burn and to ravage the cultivated parts of south London, but sent her troops across the river to ravage the north bank. The Empress felt that she was safe within the walls. But suddenly, at the hour of dinner, the great bell of St. Paul’s rang out, and the citizens, obedient to the call, clutched their arms and rushed to Paul’s Cross. The Empress was not296 in the Tower, but in a house or palace near Ludgate. With her followers she had just time to gallop through the gate and escape: her barons deserted her, each making for his own estates; and the London mob pillaged everything they could find in the deserted quarters. Then they threw open the gates of London Bridge and admitted Stephen’s Queen; this done, they besieged the Tower, which was commanded by Geoffrey de Mandeville.

The Empress had stayed in London no more than three or four days. During this time, or perhaps before her entry into the City, she granted a Charter to Geoffrey de Mandeville, in which she recognised him as Earl of Essex—“concedo ut sit comes de Essex”—she also recognised him as hereditary Constable of the Tower, and gave him certain lands.

A Charter, or letter, from the Archbishop of Rouen to the citizens of London, quoted by Round, also belongs, it would seem, though he does not give the date, to this time:—

“Hugo D. G. Rothomagensis archiepiscopus senatoribus inclitis civibus honoratis et omnibus commune London concordie gratiam, salutem eternam. Deo et vobis agimus gratias pro vestra fidelitate stabili et certa domino nostro regi Stephano jugiter impensa. Inde per regiones notae vestra nobilitas virtus et potestas.”

The Normans of Normandy, then, were watching the struggle of Norman v. Angevin in England with the greatest anxiety. The situation was changed; Stephen’s Queen was in London: but the earl was still in the Tower. It was necessary to gain him over. For this purpose she bribed him with terms which were good enough to detach him from the side of the Empress. This Charter is lost, but it is referred to by Stephen six months later as “Carta Reginæ.” There remains only one “Carta Reginæ,” which is, however, important to us because it names Gervase as the Justiciar of London (see p. 285).

Geoffrey meanwhile proved his newly-bought adherence to the King by seizing the Bishop of London in his palace at Fulham, and holding him as a prisoner. A few weeks later, Geoffrey, with a large contingent of a thousand Londoners, fully armed, was assisting at the rout of Winchester.

On the 1st of November the King was exchanged for the Earl of Gloucester. The importance of the event, as it was regarded by the City of London, is curiously proved by the date of a private London deed (Round, G. de M., p. 136): “Anno MCXLI., Id est in exitu regis Stephani de captione Roberti filii regis Henrici.”

At Christmas 1141 the King was crowned a second time, just as, fifty years later, after his captivity, Richard was crowned a second time. Round ascribes Stephen’s second Charter to Geoffrey to the same date. This Charter gave Geoffrey even better terms than he had received from the Empress. He was confirmed as Earl of Essex and as Constable of the Tower: he was made Justiciar and Sheriff of London and Middlesex: and he was confirmed as Justiciar and Sheriff of the counties of Essex297 and Hertford. The Charter acknowledges that Geoffrey was Constable of the Tower by inheritance.

In a few months, Stephen being dead, and his troops dispersed, Geoffrey went over again to the side of the Empress, and once more was rewarded by a Charter, the full meaning of which will be found in Round. It was the last of his many bargains. Matilda’s cause was lost with the fall of Oxford (December 1142).

It would seem that the first care of Stephen was to conciliate the Church, which had grievous cause for complaint. In the words of the Gesta Stephani: “because there was nothing left anywhere whole and undamaged, they had recourse to the possessions of the monasteries, or the neighbouring municipalities, or any others which they could send forth troops enough to infest. At one time they loaded their victims with false accusations and virulent abuse; at another they ground them down with vexatious claims and extortions; some they stripped of their property, either by open robbery or secret contrivance, and others they reduced to complete subjection in the most shameless manner. If any one of the reverend monks, or of the secular clergy, came to complain of the exactions laid on Church property, he was met with abuse, and abruptly silenced with outrageous threats; the servants who attended him on his journey were often severely scourged before his face, and he himself, whatever his rank and order might be, was shamefully stripped of his effects, and even his garments, and driven away or left helpless, from the severe beating to which he was subjected. These unhappy spectacles, these lamentable tragedies, as they were common throughout England, could not escape the observation of the Bishops.”

A Council was held in London as soon as the King’s cause seemed secure. It was there decreed that “any one who violated a church or churchyard, or laid violent hands on a clerk or other religious person, should be incapable of receiving absolution except from the Pope himself. It was also decreed that ploughs in the fields, and the rustics who worked at them, should be sacred, just as much as if they were in a churchyard. They also excommunicated with lighted candles all who should contravene this decree, and so the rapacity of these human kites was a little checked.” (Roger of Wendover.)

It is significant, however, that in the Gesta Stephani some of the Bishops—“not all of them, but several”—assumed arms, rode on war-horses, received their share of the booty, and imprisoned or tortured soldiers and men of wealth who fell into their hands, wherever they could.

In September 1148, after this Council, Stephen held a Court at St. Albans. Among the nobles who attended was the great earl, Geoffrey de Mandeville, a man, says Henry of Huntingdon, more regarded than the King himself. His enemies, however, calling on the King to remember his past treacheries, easily persuaded him that new treacheries were in contemplation. Perhaps the King understood that here was a subject too powerful, one who, like the Earl of Warwick later, was veritably a298 king-maker, and was readily convinced that the wisest thing would be to take a strong step and arrest him. This, in fact, he did.

Geoffrey was conveyed to London and confined in his own Tower, whither a message was brought him that he must either surrender all his castles to the King, or be hanged. He chose the former. So far as London is concerned he vanishes at this point. It is not, however, without interest to note that on his release he broke into open revolt. Like Hereward, he betook himself to the fens and the country adjacent. He seized upon Ramsey Abbey; he turned out the monks, and converted the House into a fortified post; he stabled his horses in the cloisters; he gave its manors to his followers; he ravaged the country in all directions. He was joined by large numbers of the mercenaries then in the country. He occupied a formidable position protected by the fens; he held the castle of Ely; he held strong places at Fordham, Benwick, and Wood Walton. He sacked and burned Cambridge and St. Ives, robbing even the churches of their plate and treasures: all the horrors of Stephen’s long civil wars were doubled in the ferocious career of this wild beast; the country was wasted; there was not even a plough left; no man tilled the land; every lord had his castle; every castle was a robber’s nest.

“Some, for whom their country had lost its charms, chose rather to make their home in foreign lands; others drew to the churches for protection, and constructing mean hovels in their precincts, passed their days in fear and trouble. Food being scarce, for there was a dreadful famine throughout England, some of the people disgustingly devoured the flesh of dogs and horses; others appeased their insatiable hunger with the garbage of uncooked herbs and roots; many, in all parts, sunk under the severity of the famine and died in heaps; others with their whole families went sorrowfully into voluntary banishment and disappeared. Then were seen famous cities deserted and depopulated by the death of the inhabitants of every age and sex, and fields white for the harvest, for it was near the season of autumn, but none to gather it, all having been struck down by the famine. Thus the whole aspect of England presented a scene of calamity and sorrow, misery and oppression. It tended to increase the evil, that a crowd of fierce strangers who had flocked to England in bands to take service in the wars, and who were devoid of all bowels of mercy and feelings of humanity, were scattered among the people thus suffering.”—Gesta Stephani.

Miracles were observed testifying to the wrath of God. The walls of Ramsey Abbey sweated blood. Men said that Christ and His saints slept. Yet, for their comfort, it was reported that the Lord was still watchful, because, when Geoffrey lay down to rest in the shade, behold! the grass withered away beneath him.

The end came. Happily before long Geoffrey was wounded fighting on the land of the Abbey which he had robbed; he treated his wound lightly; he rode off through Fordham to Mildenhall, and there he lay down and died. He had been299 excommunicated: he died without absolution; there was no priest among his wild soldiery, and men said openly that no one but the Pope could absolve so great a sinner. His body, enclosed in a leaden coffin, was brought to London by some Templars: they carried it to their orchard in the old Temple (at the north-east corner of Chancery Lane) and there hung it up, so that it should not pollute the ground. And the citizens of London came out to gibe at their dead foe. After twenty years Pope Alexander III. granted absolution, and the body of the great traitor at last found rest. It may be remarked, as regards the lasting hatred of the Londoners, that their enemy, whose unburied body they thus insulted, was only justiciar over them for two years or so. Great must have been his tyranny, many his iniquities, for his memory to stink for more than twenty years.

We know very little of the condition of London at this time: its trade, both export and import, must have been greatly damaged; when the Empress made her demands for money, the citizens had to assure her of their poverty and inability to comply with them; the fire of 1136, which destroyed nearly the whole City, must have involved thousands in ruin; there were factions and parties within the walls. At the same time the City possessed men and arms. London, we have seen, could send out a splendid regiment of a thousand men: not ragamuffins in leathern doublets and armed with pikes, but men in full armour completely equipped.

As regards the power of Geoffrey, it is certain that the free, proud, and independent City, the maker of kings, the possessor of charters which secured all that freemen could desire, must have been deeply humiliated at its new position of dependence upon the caprice of a soldier without honour and without loyalty: but it was only temporary. And yet we find that the City was represented at the Convention of Winchester. It is therefore certain that though London might be stripped of its charters, it had to be reckoned with. At any moment the citizens might close their gates, and then, even if the enemy garrisoned the Tower, it was doubtful whether the whole force that Matilda could command could compel the opening of their gates.

It will be shown immediately that part of Henry’s Charter, that of the possession, at least, of a City justiciar, remained in force during Stephen’s reign. It cannot be proved that the other part of the Charter, which conferred upon the City the right of electing the justiciar and the sheriffs, was also observed. Maitland says that in the year 1139 the citizens bought the right of electing their sheriffs for the sum of one hundred marks of silver. He gives no authority for the statement, of which I find no mention in Stow, Holinshed, Round or Sharpe. It would seem possible in this time of general confusion and continual war for the right to be claimed and exercised without question. It would also seem possible, for exactly the same cause, that the King would sell the right, year by year, or for the whole of his reign.

There is an episode passed over by historians which seems singularly out of300 place in a time of continual civil war. It is strange that in the year 1147, when all men’s minds in London were presumably watching the uncertain way of war, there should be found citizens who could neglect the anxieties of the time and go off crusading. This, however, actually happened. A small army—say, rather, a reinforcement, of Crusaders, consisting of Englishmen, Germans, and Flemings, sailed in company, bound for Palestine. They were led by Count Arnold of Aerschot, Christian Ghestell, Andrew of London, Vernon of Dover, and Henry Glenville. They put in at Lisbon, and instead of fighting the Saracens in Palestine, joined the Portuguese and fought the Moors at Lisbon. By their aid the city was taken, lost, and retaken. Roger de Hoveden thus comments on the expedition:—

“In the meantime a naval force, headed by no influential men, and relying upon no mighty chieftain, but only on Almighty God, inasmuch as it had set out in a humble spirit, earned the favour of God and manifested great prowess. For, though but few in number, by arms they obtained possession of a famous city of Spain, Lisbon by name, and another, called Almeida, together with the parts adjacent. How true is it that God opposes the proud, but to the humble shows grace! For the army of the king of the Franks and of the emperor was larger and better equipped than the former one, which had gained possession of Jerusalem: and yet they were crushed by a very few, and routed and demolished like webs of spiders: whereas these other poor people, whom I have just mentioned, no multitude could resist, but the greater the numbers that made head against them, the more helpless were they rendered. The greatest part of them had come from England.”

At last, after nineteen years of fighting, peace was made. Stephen was to reign as long as he lived: he was then to be succeeded by Henry. Henry of Huntingdon does justice to the general rejoicing that followed:—

“What boundless joy, what a day of rejoicing, when the king himself led the illustrious young prince through the streets of Winchester, with a splendid procession of bishops and nobles, and amidst the acclamations of the thronging people: for the king received him as his son by adoption, and acknowledged him heir to the crown. From thence he accompanied the king to London, where he was received with no less joy by the people assembled in countless numbers, and by brilliant processions, as was fitting for so great a prince. Thus, through God’s mercy, after a night of misery, peace dawned on the ruined realm of England.”

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content