Search london history from Roman times to modern day

249

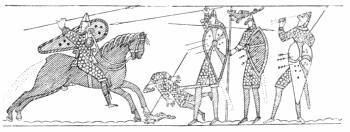

After Hastings William advanced upon the City, and finding his entrance barred, burned Southwark.

The historians commonly attribute this act, which they consider as the burning of a large and important suburb, to a threat of what the Norman would do to London herself, unless the City surrendered. This is the general interpretation of an act which I believe to have been simply the usual practice of William’s soldiers, without orders. They fired the fishermen’s huts because they always set fire to everything. Such was the way of war.

Historians, indeed, seem not to understand the position of London at this time, and the spirit of her citizens.

London, in a word, was not afraid of William. We have seen that the City had been able to beat off six successive sieges by Danes and Northmen; and this within the memory of men over forty. Are we to believe that a city with such a history of defiance and victory was going to surrender because Duke William had won a single battle? Why, King Cnut had won a dozen, yet the town would not surrender. Then, as to the burning of Southwark. That suburb was never more than one line of houses on an embankment and two along a causeway. In times of peace there stood upon the causeway certain inns for the reception of traders and250 their goods; and on the embankment certain cottages for the fishermen of the Thames and some of the river-side people, the stevedores, lightermen, and wharfmen. The inns were wooden shanties, they were mere shelters; the cottages were mere huts of wattle and daub. In time of war the inns were deserted. If there were no traders there could be no need of inns. William’s soldiers fired these deserted inns, and, at the same time, the thatch of the fishermen’s huts; not with any deep political object, but, as I have said, because they were Norman soldiers, on whose coming the villages burst into spontaneous combustion. As for the fishermen, they looked on, with their families, from a safe position in their boats in the middle of the river. When the soldiers had gone they returned and put on a new thatch. As for the City’s feeling the least alarm because these cottages were burned, nothing could be more absurd. The City looked on from the battlements of her river-wall and shouted defiance. Then William turned and rode away. He had no stomach for a long and doubtful siege of London while the new armies of the English were forming.

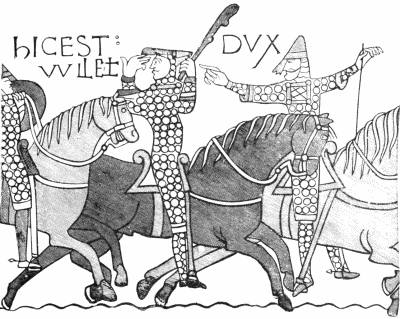

The Londoners took time to consider their next step. They had within their walls Edgar Atheling, grandson of Edmund Ironside; they had many of the Bishops; they were quite strong enough to refuse submission: but they had also among themselves many “men of Rouen”; they were already familiar with the Normans; their Bishop, William, was of French, if not of Norman, origin. They took time, then, to consider; there was no hurry; they could keep out William as long as they pleased, just as they had kept out Cnut. They began, probably on the advice of the two earls, by electing young Edgar Atheling as their king. Why, however, did William sit down at Berkhampstead? It has been suggested that he could thus cut off the earls from their earldoms. But when they wished to withdraw from London, they did so, and betook themselves to these earldoms without molestation, so that William did not cut them off. The reason for thus withdrawing is not apparent, though one can understand that the Atheling was unable to persuade or to command them to unite against the common enemy, and they retired to their own country, leaving the Londoners to themselves, seemingly without any promise or pledge to raise new armies in their own earldoms.

It is also suggested that, by harrying the country around, William was cutting off the City and depriving it of supplies. He certainly did harry the country, as is proved by the depreciation in the value of land wherever his footsteps had been (see English Historical Review, vol. xiii. No. 49). But, first of all, the harrying of the country was necessitated by the needs of the army which had to be fed; and secondly, London never was cut off: the river remained open, and Essex, once the garden of England, was not touched and still remained open.

In other words, neither the burning of Southwark, nor the harrying of the country, nor any threats of the Conqueror moved the proud City at all. She who251 had beaten off Cnut—still living in their memory as the great king—even when he had command of the river and had invaded the City by land, who had broken down six sieges of the Danes, was certainly not going to surrender at a word because the invader had won a single victory.

William, for his part, did well to consider before attacking London. Thirty years before, as he knew perfectly well, another king had ridden to London like himself, only to find the gates shut. Cnut laid siege to London: he was beaten off: he had to divide the kingdom with Edmund Ironside. Not till London admitted him was he truly King of England. William certainly knew this episode in history very well, and understood what it meant. In the north there were Saxon lords who needed nothing more than the support and encouragement of London to raise an army equal to that of Harold’s, and to march south upon him. William, who had many friends in London, therefore waited.

In London there was much running to and fro; much excitement, with angry debates, in those days. The funeral procession, simple and plain, carrying the body of Harold from the field of battle to the Abbey of Waltham, had passed through the City. It must have passed through the City, because there was no other way. The King was dead; who was to succeed him? And some said Edgar Atheling; and252 some said nay, but William himself—strong as Cnut; just as Cnut; loyal to his people as Cnut.

First they chose the Atheling, but when the great bell of St. Paul’s rang for the Folkmote, to Paul’s Cross all flocked—the craftsmen in their leathern doublets, the merchants in their cloth. All assembled together; all the citizens and freemen of the City, according to a right extending beyond the memory of man, and a custom as old as the City itself, claiming for every man the right of a voice in the management of the City.

Standing above the rest was the Bishop; silent at first amid the uproar, silent and watchful, beside him the Atheling himself, a stripling unable to wield the battle-axe of Harold; beside him, also, the Portreeve, the chief civil officer of the City; behind the Bishop stood his clergy and the canons of St. Paul’s. Outside the throng stood the “men of Rouen” and the “men of Cologne,” who had no voice or vote, but looked on in the deepest anxiety to learn the will of the people.

Then arose an aged craftsman, and after him another, and yet a third, and the burden of their words was the same: “I remember how King Cnut besieged us, and behind our walls we laughed at him.”

And all the people cried, “Yea! yea!”

“And he drew his ships by the trench that he cut in the mud round the bridge, and we fought the ships and beat him off.”

And all the people cried, “Yea! yea!”

“And we would have none but our own king, Edmund Ironside.”

And all the people cried, “Yea! yea!”

Meantime the Bishop listened and bowed his head as if in assent. And when all had spoken, he said, “Fair citizens, it is true that King Cnut besieged you and that you beat him off, like valiant citizens. Remember, however, that in the end you made Cnut your king. Was he a just king—strong in battle and in peace merciful—was he, I say, a good king?”

And all the people lifted up their voices, “Yea, yea.” For the memory of King Cnut was more precious with them than that of any other king since the great King Alfred.

Much more the Bishop said. In the end, by order, as he said, of the253 Folkmote—whom he had persuaded to their good, he set off with the Portreeve and Edgar Atheling. He was ready to offer the submission of the City on conditions. What were those conditions? They were almost certainly similar to those which the city of Exeter afterwards proposed: viz. that William should promise to be a law-abiding king. He made that promise. He entered the City, whose gates were thrown open to him.

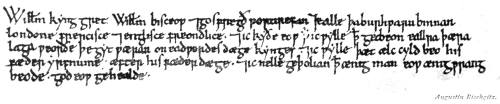

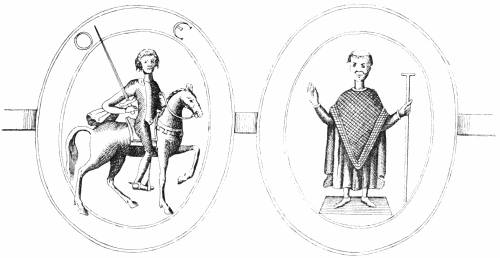

London made William king. What did William do for London in return? He gave her, probably soon after his coronation, his famous Charter. It could not have been before his coronation, because he describes himself as king, and from the nature of the contents it must have been given very shortly after his reign began. This document is written on a slip of parchment no more than six inches in length and one in breadth. It contains four lines and a quarter.

There are slight variations in the translation. The following is that of Bishop Stubbs:—

254

“William, King, greets William, Bishop, and Gosfrith, Portreeve, and all the burghers within London, French and English, friendly; and I do you to wit that I will that ye be all law worthy that were in King Edward’s day. And I will that every child be his father’s heir after his father’s day. And I will not endure that any man offer any wrong to you. God keep you.”

It is the first charter of the City.

This charter conveys in the fewest possible words the largest possible rights and privileges. It is so clear and distinct that it was certainly drawn up by the citizens themselves, who knew then—they have always known ever since—what they wanted. We can read between the lines. The citizens are saying: “Promise to grant us three points, these three points, and we will be your loyal subjects. Refuse them, and we will close our gates.” Had the points been put into words by the keenest of modern lawyers, by the most far-seeing lawyer of any time, they could not have been clearer or plainer. They leave no room at all for evasion or misconception, and they have the strength and capability of a young oak sapling.

The points were these: Every man was to have the rights of a freeman, as those rights were then understood, and according to the Saxon customs.

Secondly, every man was to inherit his father’s estate.

Thirdly, the King would suffer no man to do them wrong.

Consider what has grown out of these three clauses. From the first we have derived the right, among other things, for which every man of our race would fight to the death—the right of trial by our fellow-citizens, i.e. by jury. I do not say that the citizens understood what we call Trial by Jury, but I do say that without this clause, trial by jury could not have grown up. London did not invent the popular method of getting justice; but she did preserve the rights of the freeman, as understood by Angle, Saxon, and Jute alike, and by that act preserved for all her children developments yet to come; among others, this method of trial, which has always impressed our people with the belief that it is the best way of getting justice that has yet been invented.

As for the second, the right of inheritance. This right, which includes the right of bequest, carries with it the chief spring of enterprise, industry, invention, and courage. Who would work if the fruits of his work were to be taken from his children at his death by a feudal lord? The freeman works with all his heart for himself and his family; the slave works as little as he can for his master. The bestowal of this right was actually equivalent to a grant—a grant by charter—to the City—of the spirit of enterprise and courage. Who would venture into hostile seas, and run the gauntlet of pirates, and risk storm and shipwreck, if his gains were to be swept into the treasury of a feudal lord?

As for the third point, the promise of personal protection, London was left with no one to stand between the City and the King. There never has been any one between the King and the City. In other cities there were actually three255 over-lords—king, bishop, earl,—and the rights of each one had to be separately considered. The citizens of London have always claimed, and have always enjoyed, the privilege of direct communication with the sovereign. No one, neither earl nor bishop, has stood between them and their King, or claimed any rights over the City.

Now these liberties, and others that have sprung from them, we have enjoyed so long that they have become part of ourselves. They are like the air we breathe. When an Australian or an American builds a new town, he brings with him, without thinking of it, the rights of the freeman, the right of inheritance, the right of owning no master but the State. We cannot understand a condition of society in which these rights could be withheld. Picture to yourself, if you can, a country in which256 the king imposed his own judges upon the people; a king who could order them as he pleased; could sentence, fine, banish, imprison or hang without any power of appeal; who could make in his own interest his own laws without consulting any one; who could seize estates at their owner’s death and could give the heirs what he pleased, as much or as little; who could hand these heirs over to be the prey of a feudal lord, who only suffered them to live in order that he might rob them. That was the position of a city under a feudal lord, but it was never the position of London.

It must be added that William’s Charter conferred no new liberties or privileges upon the City. London asked for none: the City was content with what it had. William surrendered none of the power or authority of the sovereign. London asked for no such surrender. We shall see, in the charters which followed, how jealously the royal authority was guarded.

From a modern point of view it would seem an unpatriotic thing for the City to throw over the Saxon heir; but we must remember that Cnut, the best and strongest king they had had since Alfred, was a Dane, that the City was full of Normans, and that the memory of the Saxon Ethelred was still rankling among them. What better argument could the Bishop advance than the fact that William was known everywhere to be a just man, faithful to his word, and strong—the strongest man in western Europe? Above all things the country desired in a king, then and always, so long as kings ruled and after kings began to reign, was that he should be strong and faithful to his word.

The principal citizens24—among them Edgar Atheling himself—rode forth, met William, and giving hostages, made their submission, and he “concluded a treaty with them,” that is, he promised to respect their laws. According to the A.S. Chronicle, William “vowed that he would be a loving lord” to the City.

William was crowned at Westminster. It is uncertain whether the rival whom he had slain had been crowned at Westminster or at St. Paul’s—probably the latter, as the cathedral church of London. William, in that case, was the first of our kings to be crowned at Westminster. The place was chosen because it contained the tomb of the Confessor, to whom William claimed to succeed by right.

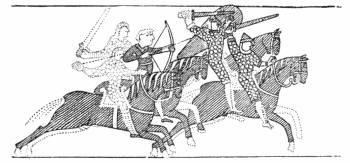

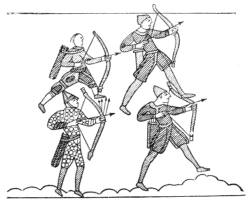

Dean Stanley has told the story of this memorable coronation with graphic hand. It was on Christmas Day. The vast Cathedral, which, newly built, was filled with the burgesses of London—sturdy craftsmen for the most part—“lithsmen” or sailors, merchants—anxious to know whether the old custom would be observed of recognising the voice of the people. It would: every old custom would be jealously observed. But there was suspicion: outside, the Cathedral was guarded by companies of Norman horse. Two prelates performed the ceremony: for the Normans, Godfrey, Bishop of Coutances; for the English, Aldred, Archbishop of257 York. Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury, had fled into Scotland. When the time came for the popular acclamation, both Bishops addressed the people. Then came the old Saxon shout of election, “Yea—yea.” The Norman soldiers, thinking this to be an outbreak of rebellion, set fire to the Abbey Gates—why did they fire the Gates?—upon which the whole multitude, Saxon and Norman together, poured out in terror, leaving William alone in the church with the two Bishops and the Benedictine monks of St. Peter’s. A stranger coronation was never seen!

Stanley points out the connection, which was kept up, of the Regalia with King Edward the Confessor.

“The Regalia were strictly Anglo-Saxon, by their traditional names: the crown of Alfred, or of St. Edward, for the King; the crown of Edith, wife of the Confessor, for the Queen. The sceptre with the dove was the reminiscence of Edward’s peaceful days after the expulsion of the Danes. The gloves were a perpetual reminder of his abolition of the Danegelt—a token that the King’s hands should be moderate in taking taxes. The ring with which, as the Doge to the Adriatic, so the King to his people was wedded, was the ring of the pilgrim. The coronation robe of Edward was solemnly exhibited in the Abbey twice a year, at Christmas and on the festival of its patron saints, St. Peter and St. Paul. The ‘great stone chalice,’ which was borne by the Chancellor to the altar, out of which the Abbot of Westminster administered the sacramental wine, was believed to have been prized at a high sum ‘in Saint Edward’s days.’ If after the anointing the King’s hair was not smooth, there was King Edward’s ‘ivory comb for that end.’ The form of the258 oath, retained till the time of James II., was to observe ‘the laws of the glorious Confessor.’ A copy of the Gospels, purporting to have belonged to Athelstane, was the book which was handed down as that on which, for centuries, the coronation oath had been taken. On the arras hung round the choir, at least from the thirteenth century, was the representation of the ceremony, with words which remind us of the analogous inscription in St. John Lateran, expressive of the peculiar privileges of the place:—

The Church of Westminster was called, in consequence, ‘the head, crown, and diadem of the kingdom.’

The Abbot of Westminster was the authorised instructor to prepare each new king for the solemnities of the coronation, as if for confirmation; visiting him two days before, to inform him of the observances, and to warn him to shrive and cleanse his conscience before the holy anointing. If he was ill, the Prior (as now the Subdean) took his place. He was also charged with the singular office of administering the chalice to the King and Queen, as a sign of their conjugal unity, after their reception of the sacrament from the Archbishop. The Convent on that day was to be provided, at the royal expense, with 100 simnels (that is, cakes) of the best bread, a gallon of wine, and as many fish as became the royal dignity.”

259

The coronation happily over, William began to build his Tower. The City should be fortified against an enemy by its strong wall—the stronger the better—but he was not going to allow it to be fortified against himself. Therefore he would build one Tower on the east and another on the west of the City wall, so that he could command ingress or egress, and also the river above or below the bridge. The Tower on the east became the great White Tower, that in the west was the Castle Montfichet. He was, however, in no hurry to build the greater fortress: the City was loyal and well disposed, he would wait: besides, he had already one foot in the City in Montfichet Tower. So it was not until eleven years after Hastings that he commanded Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester, to undertake the work. The history of the Tower will be found in its place. It took more than thirty years to build.

One of the many great fires which have from time to time ravaged London occurred in 1077, and another in 1087 or 1088; this burned St. Paul’s. Maurice, Bishop of London, began at once to rebuild it. Matthew of Westminster, writing at the beginning of the fourteenth century, says “necdum perfectum est.”

It is a great pity that William’s Domesday Book does not include London. Had it done so, we should have had a Directory, a Survey, of the Norman City. We should have known the extent of the population, the actual trades, the wealth, the civic offices, the markets, motes, hustings, all. What we know, it is true, amounts to a good deal; it seems as if we know all; only those who try to restore the life of early London can understand the gaps in our knowledge, and the many dark places into which we vainly try to peer.

260

A second Charter granted by William the Conqueror is also preserved at the Guildhall. It is translated as follows:—

“William the King friendly, salutes William the Bishop and Sweyn the Sheriff, and all my Thanes in East Saxony, whom I hereby acquaint that I have granted to Deorman my man, the hide of land at Geddesdune, of which he was deprived. And I will not suffer either the French or the English to hurt them in anything.”

Of this Deorman or Derman, Round (Commune of London, p. 106) makes mention. Among the witnesses to a Charter by Geoffrey de Mandeville, occurs the name of “Thierri son of Deorman.” It is impossible not to suppose that this “Deorman” is the same as William’s “man” of the Charter. Thierri belonged to a rich and prosperous family; his son Bertram held his grandfather’s property at Navington Barrow in Islington, and was a benefactor to the nuns of Clerkenwell. Bertram’s son Thomas bestowed a serf upon St. Paul’s about the beginning of the thirteenth century.

It has always been stated that William the Conqueror brought Jews over with him. But Mr. Joseph Jacobs (Jews of Angevin England), investigating this tradition, inclines to believe that there were no Jews in England before the year 1073 or thereabouts, when there is evidence of their residence in London, Oxford, and Cambridge. Their appointed residence in London was Old Jewry, north of Cheapside.

Stanley recalls the memory of one of those mediæval miracles which seem invented in a spirit of allegory in order to teach or to illustrate some great truth. It was a miracle performed at the tomb of Edward the Confessor:—

“When, after the revolution of the Norman Conquest, a French and foreign hierarchy was substituted for the native prelates, one Saxon bishop alone remained—Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester. A Council was summoned to Westminster, over which the Norman king and the Norman primate presided, and Wulfstan was declared incapable of holding his office because he could not speak French. The old man, down to this moment compliant even to excess, was inspired with unusual energy. He walked from St. Catherine’s Chapel, where the Council was held, straight into the Abbey. The King and the prelates followed. He laid his pastoral staff on the Confessor’s tomb before the high altar. First he spoke in Saxon to the dead king: ‘Edward, thou gavest me the staff: to thee I return it.’ Then, with the best Norman words that he could command, he turned to the living king: ‘A better than thou gave it to me—take it if thou canst.’ It remained fixed in the solid stone, and Wulfstan was left at peace in his see. Long afterwards King John, in arguing for the supremacy of the Crown of England in matters ecclesiastical, urged this story at length in answer to the claims of the Papal Legate. Pandulf answered, with a sneer, that John was more like the Conqueror than the261 Confessor. But, in fact, John had rightly discerned the principle at stake, and the legend expressed the deep-seated feeling of the English people, that in the English Crown and Law lies the true safeguard of the rights of the English clergy. Edward the Confessor’s tomb thus, like the Abbey which incases it, contains an aspect of the complex union of Church and State, of which all English history is a practical fulfilment.” (Westminster Abbey, p. 35.)

The City already contained a mixed population of Saxons, Danes, Normans—“men of Rouen,” and Germans—“men of the Emperor.” There were also Norwegians, Flemings, Gascons, and others of foreign descent in the City when William succeeded. Without insisting too strongly on the actual magnitude of the trade, small indeed compared with that which was to follow, we may point to this gathering of various peoples as a proof that the trade of London was already considered by the whole of western Europe as considerable, and, indeed, of the highest importance. Many more Normans came over after the Conquest. It is said that they chose London in preference to Rouen, because it was “fitter for their trade, and better stored with the merchandise in which they were wont to traffic.” There was also a large settlement of craftsmen in London and in other towns; among them, especially, were weavers and builders. Of these the weavers became, and remained for many generations, extremely unpopular. Cunningham (Growth of English Industry and Commerce, p. 179) suggests an explanation for the otherwise unintelligible hostility of the people towards the weavers. He thinks that before the Conquest weaving was not a national industry; that weavers were brought over by William and remained foreigners, not as taking “scot and lot” with the people.

William appears to have been true to his word as regards the City: he neither oppressed the people himself, nor did he suffer others to do them any harm.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content