Search london history from Roman times to modern day

243

As for the monuments which remain of Saxon London there are none; the Roman monuments are older, the mediæval monuments are later. There is not one single stone in the City of London which may be called Saxon. In Westminster the fire of 1835 swept away the buildings which belonged perhaps to Cnut; certainly, with alterations, to Edward the Confessor. Some of the bases of Edward’s columns still exist under the later pavement; the chapel of the Pyx, and portions of the domestic buildings appropriated to the use of the school, were built by Edward.

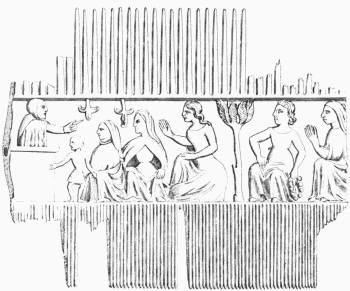

ANCIENT ENAMELLED OUCHE IN GOLD

DISCOVERED NEAR DOWGATE HILL; PROBABLY 9TH CENTURY

Roach Smith’s Catalogue of London Antiquities.

Of Saxon coins many have been found. Perhaps the most important find happened on June 24th, 1774, in clearing away the foundations of certain old houses near to the church of St. Mary at Hill, when a quantity of coins and other things placed in an earthen vessel eighteen or twenty inches beneath the brick pavement or cellar were dug up. The vessel was broken by the pickaxe and the coins fell out upon the ground. The workmen, thinking from their blackened appearance that they were worthless, threw them away, but a foreman, finding that they were silver, collected all he could, some three or four hundred pieces. Within the earthen vessel was a smaller one containing coins in a high state of preservation, together with a fibula of gold finely worked in filigree, with a sapphire set in the centre, and four pearls, of which one was lost. The coins consisted entirely of pennies of Edward the Confessor, Harold II., and William the Conqueror. They are stamped with the name of the Moneyer and the place where he kept his Mint. The Minters or Moneyers belonging to London were:—

(1) Under Edward the Confessor:

Durman, Edwin, Godwin, Wulfred, Sulfine, and Wulfgar.

244

(2) Under Harold:

Edwin, Gefric, Godric, Leofti, and Wulgar.

(3) Under William:

Ægelric, Ælffig, Godwine, Leofric, and Winted.

It is at first sight strange that so very little should survive of six hundred years’ occupation. Look, however, at other cities. Nothing survives except those buildings, like the pyramids, or King Herod’s temple, built of stones too huge to be carried off. What is there in Paris—in Marseilles—in Bordeaux—in any ancient city to mark the occupation of the city from the fifth to the eleventh century? Considering the character of the people; considering, too, the arts and architecture of the time; it would be strange indeed if Saxon London had left a single monument to mark its existence.

If, however, there are no buildings of Saxon origin, there are other remains. The names of streets proclaim everywhere the Saxon occupation. Thus, Chepe, Ludgate, Bishopsgate, Addle Street, Coleman Street, Garlickhithe, Edred’s Hithe (afterwards Queen’s Hithe), Lambeth Hill, Cornhill, Gracechurch Street, Billingsgate, Lothbury, Mincing Lane, Seething Lane, Aldermanbury, Watling Street, Size Lane, Walbrook, and many others, occur at once. Or, there are the churches whose dedications point to the Saxon period: as, St. Botolph, St. Osyth, St. Ethelburga, All Hallows, and others.

Streets within the City that are perhaps later than the Conquest are Fenchurch Street, Leadenhall Street, Lombard Street, Old Broad Street, Great Tower Street,245 and Tower Hill. Streets with trade names, such as Honey Lane, Wood Street, Friday Street, the Poultry, Bread Street, are almost certainly of Saxon origin.

Stow speaks of an ancient road or street running from Aldgate to Ludgate which was cut off by the enclosure of St. Paul’s Churchyard. A glance at the map will show that when West Chepe was an open market, a broad space, the way from east to west, may very well have struck across St. Paul’s Churchyard to Ludgate Hill, leaving the Cathedral, then much smaller than the Norman building, plenty of room on the south side. No traces of the Danish Conquest exist, but there are traces of Danish residence, first, in the names of the churches of St. Magnus and St. Olave, of the latter there were many; in the name of St. Clement Danes, which perhaps preserves the memory of a Danish quarter, but the subject is obscure; in the Court called the Hustings, held every Monday, the name of which is certainly derived from the Danes. The similarity, however, of Danish and Saxon institutions made the adoption of the latter easy. The absorption of the Danes by the Saxons was in a few years so complete that no memory was left to their descendants of their Scandinavian origin. In London the families of Danish descent were like those of Flemish or Norman descent: they saw no reason to remember their origin, and were English as well as London citizens.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content