Search london history from Roman times to modern day

176

It is sometimes said that one of the earliest acts of King Alfred in gaining possession of London was to build a fortress or tower within the City. The authority for this statement seems to be nothing more than a passage in the Chronicle, under the year 896. “Then on a certain day the king rode up along the river and observed where the river might be obstructed, so that the Danes would be unable to bring up their ships. And they then did thus. They constructed two fortresses on the two sides of the river.” This seems but a slender foundation for the assumption of Freeman that Alfred built a citadel for the defence of London. “The germ of that tower which was to be first the dwelling-place of kings and then the scene of the martyrdom of their victims.” I see no reason at all for the construction of any fortress within the City except the reason which impelled William to build the White Tower, viz. in order to keep a hold over the powerful City. And this reason certainly did not influence Alfred. It is quite possible that Alfred did strengthen the City by the construction of a fortress, though such a building was by no means in accordance with the Saxon practice. It is further quite possible that he built such a tower on the site where William’s tower stood later; but it seems to me almost inconceivable that Alfred, if he wanted to build a tower, should not have reconstructed and repaired the old Roman citadel, of which the foundations were still visible. I confess that I am doubtful about the fortress. What Alfred really did, as I read the Chronicle, was to construct two temporary forts near the mouth of the Thames, so as to prevent the Danish ships from getting out. He caught them in a trap.

Let us renew the course of the Danish invasions so far as they concern London. In 893 one army of Danes landed on the eastern shores of Kent and another at the mouth of the Thames. In 894 King Alfred fought them and defeated them, getting back the booty. Some of the Danes took to their ships and sailed round to the west, whither the King pursued them. Others fled to a place near Canvey Island called Bamfleet, where they fortified themselves. Then, for the first time after the Conquest, we find that London is once more powerful, and once more filled with valiant citizens. For the Londoners marched out under Ethelred, Earl of Mercia,177 their governor, attacked the Danes in their stronghold, took it, put the enemy to flight, and returned to London with all that was within the fort, including the women and the children. In 895 the Danes brought their ships up the Thames and towed them up the Lea to the town of Ware, but the year afterwards the Londoners made their ships useless: whereupon the Danes abandoned them, and the men of London took or destroyed them. Maitland says that “a few years ago”—he writes in 1786—“at the erection of Stanstead Bridge, remains of these ships were found.”

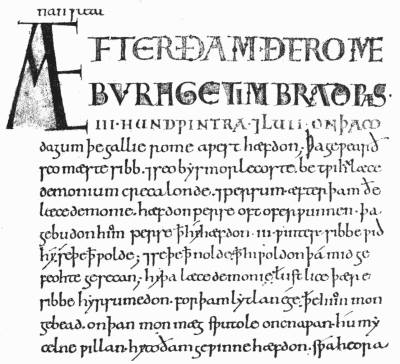

King Alfred was able to equip and to send out an efficient fleet. In the year 901, to accept the generally received date, which now appears, however, more than doubtful, the great King Alfred passed away. No king or captain, in the whole history of London, ever did so much for the City as Alfred. Circumstances, chance, geographical position, created London for the Romans, and restored it for the Saxons. Circumstances, not the wisdom of kings, gave London, in after ages, its charters and its liberties. It is the especial glory of Alfred that he discerned the importance of the City, not only for purposes of trade, but as a bulwark of national defence. He repaired the strong walls which, in a time when ladders and mines were not yet part of the equipment of war, made the City impregnable; he gave security to merchants; he offered a place of safety to princesses and great ladies; a treasure-house which could not be broken into and a rallying-place for fugitives. He gave the newly-born City a strong governor and a strong government; he made it possible, as was shown two hundred years later, to maintain the independence of the people even though the whole country except this one stronghold should be overrun. London continued under the rule of Ethelred, Earl of the Mercians, till178 his death in 912, when King Edward “took possession of London.” In 917 there was fighting with the Danes in Mercia, and in 918 about Hereford and Gloucester; from 919 till his death in 924, King Edward was continually occupied in fighting and in fortifying towns. By King Athelstan was fought and won the great battle of Brunanburgh, when there was slain five kings and seven earls. This victory, Maitland says, was “chiefly obtained by the bravery of the Londoners, who were the best troops in the army.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not say anything about the London troops.

179

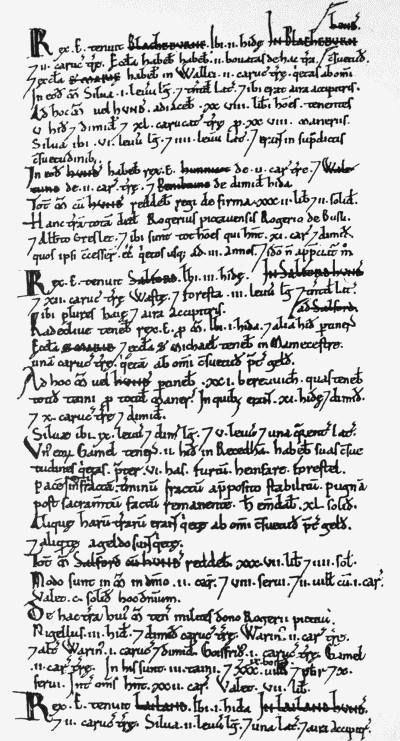

Maitland points out, as an indication that London was now in flourishing condition, the fact that Athelstan, in apportioning the number of coiners for each town, allotted to London and Canterbury the same number, and that the highest number. To consider this an indication of prosperity is indeed to be thankful for small mercies. To me it is a clear proof, on the other hand, of the comparative decline of London, since she was considered of no greater importance than Canterbury.

At this period, however, the cities of England, all of which without exception had been taken and devastated by the “army,” had sunk to a point of poverty as low as any touched even in the fifth and sixth century—those centuries of battle and disaster,—and perhaps lower, for the Saxons were slow in becoming residents180 in a walled city, and would be ready to return if possible to the old life in the open.

Let us go back to the Chronicle. In the year 945, King Edmund held a Witenagemot in London, chiefly occupied with ecclesiastical affairs.

During the reigns of Edmund and Edred (940-955) there was fighting in Northumberland, but no new incursions of the Danes. Under the powerful rule of Edgar there was an almost unbroken peace of seventeen years. In 979 began the disastrous reign of Ethelred, when the Danish incursions were renewed on a larger scale, and when the glory of England departed.

Let me here quote the opinion of Freeman as to the position of London at this time.

“The importance of that great city was daily growing throughout these times. We cannot as yet call it the capital of the kingdom, but its geographical position made it one of the chief bulwarks of the land, and there was no part of the realm whose people could outdo the patriotism and courage of its valiant citizens. London at this time fills much the same place in England which Paris filled in Northern Gaul a century earlier. The two cities, in their several lands, were two great fortresses, placed on the two great rivers of the country, the special objects of attack on the part of the invaders, and the special defence of the country against them. Each was, as it were, marked out by great public services to become the capital of the whole kingdom. But Paris became a national capital only because its local count grew into a national king. London, amidst all changes within and without, has always kept more or less of her ancient character as a free city. Paris was a military bulwark, the dwelling-place of a ducal or a royal sovereign; London, no less important as a military post, had also a greatness which rested on a surer foundation. London, like a few other of our great cities, is one of the ties which connect our Teutonic England with the Celtic and Roman Britain of earlier times. Her British name still lives on, unchanged by the Teutonic conquerors. Before we first hear of London as an English city she had cast away her Roman and Imperial title: she was no longer Augusta: she had taken again her ancient name, and through all changes she clave to her ancient character. The commercial fame of London dates from the early days of Roman dominion. The English Conquest may have caused an interruption for a while, but it was only for a while. As early as the days of Æthelberht the commerce of London was again renowned. Ælfred had rescued the city from the Dane; he had built a citadel for her defence, the germ of that Tower which was to be first the dwelling-place of kings, and then the scene of the martyrdom of their victims. Among the laws of Æthelstan none are more remarkable than those which deal with the internal affairs of London and with the regulation of her earliest commercial corporations. During the reign of Æthelred the merchant city again became the object of special and favourable181 legislation. His institutes speak of a commerce spread all over the lands that bordered on the western ocean. Flemings and Frenchmen, men of Ponthieu, of Brabant, and of Luttich, filled her markets with their wares and enriched the civic coffers with their toils. Thither, too, came the men of Rouen, whose descendants were, at no distant day, to form no small element among her own citizens. And worthy and favoured above all, came the seafaring men of the Old-Saxon brotherland, and pioneers of the mighty Hansa of the North, which was in days to come to knit together London and Novogorod in one bond of commerce, and to dictate laws and distribute crowns among the nations by whom London was now threatened. The demand for toll and tribute fell lightly on those whom English legislation distinguished as the men of the Emperor.”

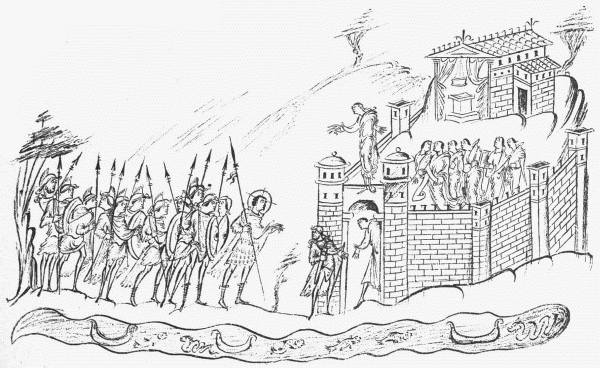

The part played by London in the country during the momentous hundred182 years following Ethelred’s accession shows the importance of the City. That Londoners fought at Maldon is not to be doubted. That year witnessed the shameful buying of peace from the pirates whom the English had been defeating and defying since the days of Alfred. It was hoped by the Danes to renew the bribe of 991 in the year following. They came up the Thames, but they were met by the Londoners with their fleet and defeated with great slaughter. In the following year Bamborough was taken by the Danes and the north country ravaged. In the year 994, after the news of the taking of Bamborough and the flight of the Thanes at Lindesey, encouraged by their successes, the Danes attempted an invasion on a far more serious scale. This time the leaders were Olaf, King of the Norwegians, and Swegen, King of the Danes. They sailed up the Thames with a fleet of ninety-four ships. The invaders arrived at London and delivered an assault upon the wall. It must be remembered that the river side of the wall was then standing. We are not informed whether the town was attacked from the land side or the river side. The attack was, however, repelled with so much determination, and with such loss to the besiegers, that the two kings abandoned the attempt that same day and sailed away. The victory and the safety of the City were attributed to the “mild-heartedness of the holy Mother of God.”

As for the Northmen, since they could not pillage London they would ravage the coast; and, taking horses, they rode through the eastern and southern shores, pillaging and ravaging and murdering man, woman, and child. These large words must not be taken to imply too much. When a band of marauders rode through the country, especially a country with only a few roads or tracks, they were limited in their field of robberies by the limited number of roads, by the distances between the settled places, by their own desire to return as quickly as possible, and by their inability to carry more than a certain amount of booty. Two or three small loops drawn inland from the anchorage of their ships would mark the extent of their forays from that part. However, they were bought off. In this case Olaf kept his word. He was a Christian already, but he received confirmation from Bishop Ælfreah, and on his return to his own country he spent the rest of his life in promoting Christianity. In St. Olave, Silver Street; St. Olave, Hart Street; St. Olave, Jewry; and St. Olave, Tooley Street, we have four churches erected to the memory of the saintly Northman who kept his word, and, having promised to return no more, stayed in his own country.

Swegen came back, though after some delay, to revenge the foulest treachery. It was that of England’s Bartholomew Day, when, by order of King Ethelred, certainly the very worst king who ever ruined his generation, all the Danes in the land were treacherously murdered at one time. Among those victims was Gunhilda, Swegen’s own sister, with her husband and her son. Swegen came over and landed at Sandwich. It was nine years since the payment of Olaf and himself.183 During these nine miserable years there had been an unbroken series of defeats and humiliations, with the treacheries and jealousies and quarrels which in rude times follow in the train of a weak king. Swegen made himself master of the whole kingdom except London. He attempted the siege of the City with a mighty host; he assaulted the walls; and he was beaten back. As ten years before, he wasted no time in trying to take a place too strongly fortified and defended. Ethelred, however, deserted the town, retiring to the Isle of Wight with his ships. Queen Emma went over to Normandy, taking her sons Edward and Alfred; and London, having no longer a king to fight for, opened her doors to the Danish conqueror.

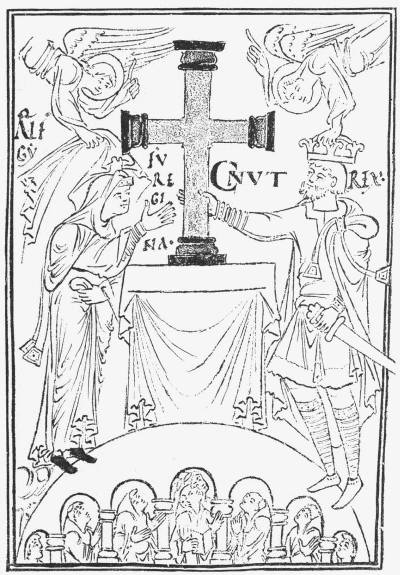

Swegen died immediately afterwards. He left two sons: Harold, who succeeded to the Danish kingdom, and Cnut, a youth of nineteen, who was proclaimed King by the Danish fleet. What follows was certainly done at London. “Then counselled all the Witan who were in England, clergy and laity, that they should send after King Ethelred: and they declared that no lord was dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would rule them better than he had before done. Then sent the King his son Edward hither with his messengers and ordered them to greet all his people: and to say that he would be to them a loving lord and amend all those things which they abhorred, and each of those things would be forgiven which had been done or said to him on condition that they all with one consent would be obedient to him without deceit. And they there established full friendship, by word and by pledge, on either hand.... Then during Lent King Ethelred came home to his own people: and he was gladly received by them all.” He also promised to govern by the advice of his Witan.

184

There followed the defeat of Cnut, who sailed away to Denmark; the marriage of Edmund Atheling with the widow of the murdered Segefrith; the return of Cnut; the treachery of Eadric; and the loss of southern England. Edmund, however, held out in the north for a time: finally, Cnut overran the north as well as the south, and all England, except London, was in his power. He proposed an expedition against London. While on his way thither he heard that King Ethelred was dead. He called a gemot of the Witan. All who were without the walls of London assembled at Southampton and chose Cnut as the lawful King of England. At the same time the smaller body which was within London chose Edmund king. He was crowned, not at Kingston in Surrey, the usual place for coronations, where still may be seen the sacred stone of record, but at St. Paul’s in London.

The history of the wonderful year that followed belongs to the country rather than to London. It was the year when one great and strong man restored their spirit to a disgraced and degraded people; won back a good half of the land; and, if he had lived, would have reconquered the rest—the year of Edmund Ironside. On St. Andrew’s Day, some months after his father, this great soldier died in London. They buried him in the Minster of Glastonbury, which held the bones of Edgar.

It was at the beginning of this short reign that Cnut commenced the famous siege of London. “The ships came to Greenwich at Rogation days. And within a little space they went to London and dug a great ditch on the south side and dragged their ships to the west side of the bridge; and then afterwards they ditched the city round, so that no one could go either in or out: and they repeatedly fought against the city; but the citizens strenuously withstood them. Then had King Edmund, before that, gone out: and then he overran Wessex and all the people submitted to him.” Thus the Chronicle. The siege was raised by the arrival of Edmund.

This is a very brief and bald account of a most memorable event. We learn two or three things from it—first, that in some way or other the citizens made the passage of the bridge impossible, yet twenty years later Earl Godwin’s ships passed through the southern arches. He, it is true, had previously secured the goodwill of the Londoners. It is possible that, in the case of Cnut, they may have barred the way by chains. It is, next, certain that the river wall was standing, otherwise an attack upon the south of the City would have been attempted. London was secure within its wall, which ran all round it. The Danes had no knowledge of sieges: they had neither battering rams, nor ladders, nor any means of attacking a wall: they never even thought of mining. It is, next, certain either that the population of London was so large as to man the whole wall, a thing difficult to believe, or that the Danish army was so small that it could only attack at certain points. And it is also certain that the Danes could not keep out supplies; the way was open either into Kent or into Essex or to the north. The account also makes it clear that the185 bridge had been repaired; that it was maintained in good order; and that it was strongly fortified. Cnut, it is evident, did not propose to attempt the City by means of the bridge.

Let us now go back a little in order to consider the condition of the bridge and the story of King Cnut’s trench. It is not certain whether the Saxons at the time of their first settlement kept the bridge in repair; the intercourse between the King of Kent and the King of the East Saxons may possibly have been carried on by a ferry. At the same time it was so easy to keep the bridge open that one feels confident that it was maintained. When the Danes got possession of London their movements are pretty closely followed, but no mention is made of the bridge. I am inclined to think that during their occupation the piles stood up across the river, partly stripped of their upper beams, and that it was Alfred who repaired the bridge when he repaired the wall. That the bridge was standing and in good repair in the time of King Edgar is proved by the curious story of the witch and her punishment which belongs to that time (see p. 222).

“In the year 993,” says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “came Olaf with 90 ships to Staines and ravaged thereabouts; and went thence to Sandwich, and so thence to Ipswich, and that all overran, and so to Maldon.” How, it is asked, would Olaf sail past the bridge? There can be two answers to this question. It looks, to begin with, considering that Sandwich, Ipswich, and Maldon all lie close together,186 near or on the coast, as if Olaf had no business at Staines at all. Why, Staines is 120 miles from the North Foreland, round which the fleet must sail. And the answer to the question is, therefore, that some other place is intended. If, however, Olaf did really sail up the river to Staines, then the bridge must have been in a ruinous condition. But the stout piles remained, or at least as many of them as were wanted to show how the work could be restored or rebuilt. Snorri Sturlason, the Icelander, who wrote in the thirteenth century, has preserved a curious account of the bridge (Chronicles of London Bridge, p. 16).

“They—that is, the Danish forces—first came to shore at London, where their ships were to remain, and the City was taken by the Danes. Upon the other side of the River is situate a great market called Southwark—Sudurvirke in the original—which the Danes fortified with many defences; framing, for instance, a high and broad ditch, having a pile or rampart within it, formed of wood, stone, and turf, with a large garrison placed there to strengthen it. This the King Ethelred—his name, you know, is Adalradr in the original—attacked and forcibly fought against; but by the resistance of the Danes it proved but a vain endeavour. There was, at that time, a Bridge erected over the River between the city and Southwark, so wide, that if two carriages met they could pass each other. At the sides of the Bridge, at those parts which looked upon the River, were erected Ramparts and Castles that were defended on the top by pent-house bulwarks and sheltered turrets, covering to the breasts those who were fighting in them; the Bridge itself was also sustained by piles which were fixed in the bed of the River. An attack, therefore, being made, the forces occupying the Bridge fully defended it. King Ethelred being thereby enraged, yet anxiously desirous of finding out some means by which he might gain the Bridge, at once assembled the Chiefs of the army to a conference on the best method of destroying it. Upon this, King Olaf engaged—for you will remember he was an ally of Ethelred—that if the Chiefs of the army would support him with their forces, he would make an attack upon it with his ships. It being ordained then in187 council that the army should be marched against the Bridge, each one made himself ready for a simultaneous movement both of the ships and of the land forces.”

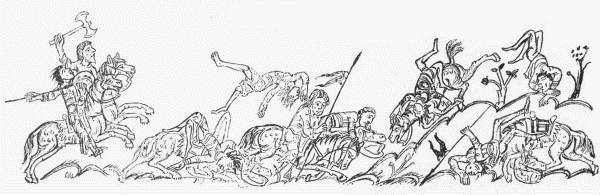

King Olaf then constructed a kind of raft or scaffold which he placed round his ships so that his men could stand upon them and work. As soon as they reached the bridge they were assailed by a hail-storm of missiles, which broke their shields, and forced many of the ships to retire. Those that remained, however, made fast the ships with ropes and cables. Then the rowers tugged their hardest; the tide turned in their favour; and crash! down fell that part of the bridge and all the people who were on it into the river. Thus Ethelred was restored. In memory of this exploit the Norse Bard sang:—

“And thou hast overthrown their Bridges, Oh thou Storm of the Sons of Odin; skilful and foremost in the Battle! For thee was it happily reserved to possess the land of London’s winding City. Many were the shields which were grasped sword in hand, to the mighty increase of the conflict; but by thee were the iron-banded coats of mail broken and destroyed....

Thou, thou hast come, Defender of the Earth, and hast restored into his kingdom the exiled Ethelred. By thine aid is he advantaged, and made strong by thy valour and prowess; Bitterest was that Battle in which thou didst engage. Now in the presence of thy kindred the adjacent lands are at rest, where Edmund, the relation of the country and the people, formerly governed.”

There is nothing about all this in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It may have happened; but it could not have been invented with a stone bridge in view, the piers of which all King Olaf’s ships together could not move. Of a wooden bridge constructed in the way described above the thing seems quite possible.

The next event in the history of the bridge is the unsuccessful siege by Cnut. In the course of this siege the besiegers dug the trench round the south end of the bridge and dragged their ships through it, so as to attack London all along the river face. Maitland, the historian, pleased himself by thinking that he had discovered vestiges of the trench all the way round. In his time (circa 1740) there were meadows and pastures and orchards over the whole of south London.

“By a diligent search of several days,” Maitland says, “I discovered the vestigia and length of this artificial water-course: its outflux from the river Thames was where the Great Wet Dock below Rotherhithe is situate: whence, running due west by the seven houses in Rotherhithe Fields, it continues its course by a gentle winding to the Drain Windmill: and, with a west-north-west course passing St. Thomas of Watering’s, by an easy turning it crosses the Deptford Road, a little to the south-east of the Lock-Hospital, at the lower end of Kent Street; and, proceeding to Newington Butts, intersects the road a little south of the turnpike; whence, continuing its course by the Black Prince in Lambeth Road, on the north of Kennington, it runs west-and-by-south, through the Spring garden at Vauxhall, to its influx into the Thames at the lower end of Chelsea Reach.”

The position of this trench has been the subject of much discussion. I submit the following as a reasonable solution of the question:—

188

Why should it have been a long canal? The conditions of the work were exactly the same whatever place should be selected, viz. the Danes would have to dig through the river embankment on both sides of the bridge. They would also have to dig through the causeway. In the latter part of the work certainly, and in the former part probably, they would have to remove buildings of some kind. The continual wars (800-1000) with the Danes make it quite certain that Southwark must then have been in a very deserted and ruinous condition.

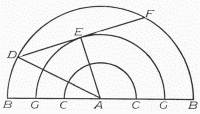

Why should Cnut make his canal a single foot longer than was necessary? We may assume that he was not so foolish. Now the shortest canal possible would be that in which he could just drag his vessels round. In other words, if a circular canal began at CB, and if we draw an imaginary circle GEG round the middle of the canal, it is evident that the chord DF, forming a tangent to the middle circle, should be at least as long as the longest vessel. I take the middle of the canal as the deepest part: there would be no time to construct a canal with vertical sides.

Now (see diagram)

If r is the radius AB or AD and 2a the breadth of the canal and 2b the length of the chord DF,

r2 = (r - a)2 + b2;

[therefore] 2ar = a2 + b2;

[therefore] r = (a2 + b2)/2a.

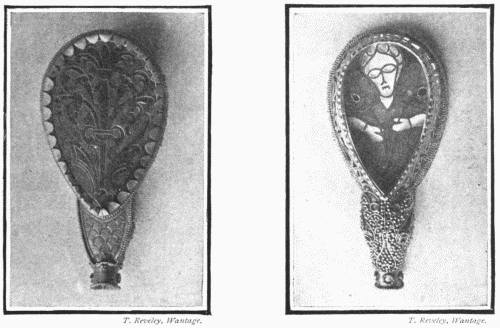

This represents the length of the radius in terms of the length of the largest vessel and the breadth of the canal, and is therefore the smallest radius possible for getting the ships through. Now the great ship found in Norway in the year 1880 is undoubtedly one of the finest of the vessels used by Danes and Norsemen. The poets speak of larger ships, but as a marvel. Nothing is said about Cnut having ships of very great size. This vessel was 68 feet in length, 16 feet in breadth, and 4 feet in depth. She drew very little water; therefore a breadth of canal equal to the breadth of the vessel would be more than enough. Let us make the chord 70 feet in length, and the breadth of the canal 16 feet. Then

2b = 70, or b = 35,

and

2a = 16; [therefore] a = 8; [therefore] r = (352 + 82)/16 = 80 (very nearly).

So that AE in this radius of the inner circle is 64 feet in length.

189

But it was by no means necessary to form a semicircle. Any canal formed in two parallel circles whose radii are 64 to 80 feet would be sufficient for the purpose. Nor would it matter how short the canal was made: a hundred feet probably represented the whole of this mighty work of Cnut, and this cutting, after breaking down the embankment and the causeway, was excavated in the soft mould of the reclaimed marsh. Where, then, are Maitland’s four miles or so?

As soon as the siege was raised and the Danes departed, the embankment was repaired; the broken causeway was filled up again; the soft earth and mud left by the short canal and the encroachments of the tide through the broken bank were speedily levelled, and all traces of the work disappeared.

This bridge was carried away by the tide in 1091. In 1097, according to the A.S. Chronicler, either the bridge had not yet been repaired, or it had again suffered. He says, “in repairing the Bridge that was nearly washed away.” The maintenance of the bridge at this time was provided for by an assessment levied on the counties of Surrey and Middlesex. It was burned down in the destructive fire of 1136. Again it was rebuilt in wood. But in the year 1176 began the building of the long-lived and illustrious bridge of stone, constructed by that great Pontifex, Peter of Colechurch. The new stone bridge was built a little to the west of the wooden bridge.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content