Search london history from Roman times to modern day

169

The Danes, then, held London for twelve years. In after years, when the country was governed by Danish kings, large numbers of Danes settled in London, and, with the national readiness to adapt themselves to new conditions and new manners (compare the quick conversion of Normans to French language and manners), they speedily became merged in the general population. Very soon we hear no more of Danes and English as separate peoples, either in London or in the country. London, indeed, has always received all, absorbed all, and turned all into Londoners. During this first Danish occupation, of which we know nothing, one of two things happened: either the occupiers settled down among the citizens, leaving them to follow their trades and crafts in their own way; or they murdered and pillaged, drove away all who could fly, and then sat down quietly and remained, an army in occupation in a strong place. Everything points to the latter course, because the ferocity of the Danes at this time was a thing almost incredible. London was, for the moment, ruined. It was not deserted by the lowest class, for the simple reason that an army requires people for the service of providing its daily wants. Food—grain and cattle—was brought in from West and East Anglia; the river supplied fish and fowl—wildfowl—in abundance. But fishermen and fowlers were wanted; therefore these useful people would not be slain, except in the first rush and excitement of victory. In the same way armourers, smiths, makers of weapons, bakers, brewers, butchers, drovers, cooks, craftsmen, and servants of all kinds are wanted, even by the rudest soldiery. In the fifth century, when the trade of London deserted her, the people had to go because the food supplies also were cut off. Since the Danish army could winter in London for twelve years, it is certain that they had command of supplies. Therefore, after the first massacres and flight, the lower classes remained in the service of their new lords. Moreover, by this time, the enemy, having resolved to stay in the country, had doubtless made the discovery that it is the worst policy possible to kill the people who were wanted to bring them supplies, or to murder the farmers who were growing crops and keeping cattle for them to devour.

The Danes occupied London for twelve years. At the best it was a bad time170 for the people who remained with them. Rough as was the London craftsman of the ninth century, he was mild and gentle compared with his Danish conqueror and master.

If we inquire whether the trade of London vanished during these years, it may be argued, first, that the desire for gain is always stronger than the fear of danger; secondly, that merchant-ships were accustomed to fight their way; thirdly, that when a strong tide or current of trade has set steadily in one direction for many years, it is not easily stopped or diverted; fourthly, that when the first massacre was over, the Danes would perhaps see the advantage of encouraging merchants to bring things, if only for their own use; for they were ready to buy weapons and wine, if nothing else, and there were a great many things which they wanted and could not make for themselves. As for the interior, there could be no trade there during the disturbed condition of the country.

A note made a hundred and fifty years later shows that the Danes did at least consume the importations of foreign merchants. When they murdered Alphage, Archbishop of Canterbury, they were drunk with wine. We cannot suppose that an army whose soldiers regarded strong drink as the greatest joy of life did not perceive the advantages of procuring wine in abundance by means of the merchants who brought it from France and Spain.

I allow the weight of these reasons. I admit that there may have been still some trade carried on at the Port of London. I shall presently give reasons for supposing, on the other hand, that London was again ruined and deserted.

Let us see what manner of men were these soldiers who became owners of London for twelve years and afterwards furnished kings to England and law-abiding burghers to the City.

We may learn their manners from the pages of the historian Saxo Grammaticus.

To begin with, the Danes were a nation of warriors, as yet not Christians. And Christianity, when it came, brought at first little softening of manners. It presented much the same Devil to the popular imagination, but with a face and figure more clearly outlined; it localised Hell, which remained much the same for the Christian as for the pagan, only it furnished more exact details and left no doubt as to the treatment and sufferings of the lost. The only honour paid to any man was that due to valour; the only thing worthy of a man’s attention was the maintenance of his strength and the increase of his courage. The king must lead in battle; he must sometimes fight battles of wager; he had his following or court of lords, who were bound to fight beside him, and to die, if necessary, with him or for him. If he should by any lucky accident escape the accidents of battle, murder, and sudden death, and so enter upon old age, he must abdicate, for a king who could no longer fight was absurd.

The Danes had troops of slaves: some born in slavery; some captives of171 war; the craftsmen of London were no doubt slaves because they were captives—they had survived the storm of the City. A slave had no rights at all; his master could do what he pleased with him; he was flogged, tortured, scorned, reviled, and brutally treated; it was a time when the joy of fighting was followed by the joy of revenge, when to make a captive noble eat the bread of servitude and drink the water of humiliation filled the victor with a savage joy. As for the women, they were reserved for the service and the lusts of the captors. It pleased the chivalry of the Dane to cast the daughters of kings into the brothel of the common soldier.

Of course they had the virtue of courage—it is, however, suspicious that, among the Danes, as in all savage nations, their courage had to be kept up by constant exhortations, charms, and songs. There were unexpected panics and routs and shameful flights of these invincible Danes as well as of the Saxons: this would seem to show that their vaunted courage was liable to occasions of failure. They were, however, marvellously free from fear of pain; they seem to have disregarded it altogether. Of one man it is related that rather than marry a certain princess who was offered him he chose to be burned to death; and in a poem it is told of another that, when he was wounded so grievously that his entrails were exposed, he refused the help of a slave because he was a slave, and the help of a woman because her birth was not noble, and so he remained till one of free and honourable birth came along, who tied him round with withies and carried him off to a house. Honour and loyalty were not so much admired as demanded. Treachery and rebellion were ruthlessly punished. In some cases the wretched criminal was tied by thongs passed under the sinews of his heels to the tails of wild bulls and then hunted to death by hounds. Other punishments there were. As for the women, those of free birth were modest172 and chaste: to be detected in an amour involved such a barbarous punishment as the cutting off of the nose.

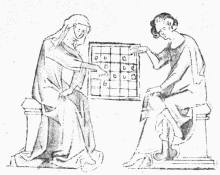

Their weapons were swords, clubs, axes, bows, slings, and stones. Those who could afford to buy them wore mail coats and helmets; they carried banners; they blew horns; they fought on foot; and the battle was decided by single combat, hand to hand, with great slaughter and prodigies of valour. Like the Red Indians, they were able to work themselves up into a kind of frenzy before fighting. Sometimes there were Amazons among them. They all messed together, king and nobles and soldiers. When at home they gathered in the great hall at night with fires blazing, with torches, and with hangings to keep out the draughts. Their food was for the most part simple—beef, mutton, pork, with huge quantities of bread. Their drink was chiefly ale, served in horns. After supper they played games. We must remember how long were the winter evenings which had to be got through. Games of some kind were necessary, and there were a great number of games. The minstrel played the harp and sang warlike songs of the deeds of great warriors. They “flyted” each other, i.e. endeavoured to reduce each other to silence by abuse and insult, a game which gave great opportunities to a man of imagination. Such specimens of173 “flyting” as remain show that it might be, and most likely was, coarse and obscene to the last degree. They told stories of their leaders and wove impossible fictions of their bravery, their endurance, and their generosity. They bragged over impossible deeds, a thing which we find the knights of the fourteenth century also doing in their game of gabe; they called in jugglers, tumblers, mimes, and singers of love-songs and drinking-songs. It is to be noted that, although they loved the acting and the singing, they held the calling of actors and minstrels in great contempt. Sometimes they tugged at a rope, as in our old game of French and English. Sometimes, when they were well drunken, they began a very favourite pastime, that of bone-throwing. It was in this way that St. Alphage was murdered. For the Danes sent for him and began to throw beef bones at him, perhaps in play, and expecting to see the Archbishop dodge the bones dexterously. He did not—one struck him on the head and he fell dead.

As for the religion of these people before and after their conversion, they believed boundlessly. They believed in giants and in dwarfs, in ghosts and in devils, in fate, in a whole array of gods and goddesses, in the Land of Undeath, in the Underground Land, in magic and sorcery, in charms and philtres, in ordeals. All these things, with modifications, they continued to believe long after they were received into the bosom of the Christian Church. And they were full of stories, legends, and traditions—a wild, imaginative people, with a limited horizon of knowledge, beyond and outside which all was blackness, with the terror of the unknown.

Such were the people who came every year with their army, harrying and plundering, murdering and destroying, till they found it more convenient to winter in the country, which they did, occupying the islands of Thanet. Such were the people who obtained possession of London; such were the people who afterwards flocked to the City in the days of King Cnut and settled down among the rest of the heterogeneous London folk.

There are no traces of this first Danish occupation. The churches dedicated to Danish saints, Magnus and Olaf, were erected afterwards. Probably the Danes at this time left not one church standing.

In 883 Alfred obtained possession of the City—“after a short siege”—the historians write. The only authority for this short siege is the paragraph in the A.S. Chronicle already quoted. “They sat down against the army of London; and there they largely obtained the object of their prayer.” After the battle of Ethandun, the Danes retired from Cirencester to Chippenham, and there wintered. In the same year another body of them collected and wintered at Fulham on the Thames. This fact makes me ask why, when London was theirs, the Danes should winter at Fulham instead of at the City itself. Surely London offered winter quarters174 superior to those of Fulham, that little village in a marsh. There seems to me no explanation except one, namely, that the City was once more deserted. The same thing which happened to Augusta may have happened also to Saxon London. The whole of its trade was destroyed; the river and the channel were in the hands of the Northmen; the City had been taken with the customary massacres and plunder; it was no longer possible to live in the place; no supplies could be taken there because there were no longer any means of buying for them or paying for them. Therefore, save for the wretched remnant of fishermen and slaves, the streets were desolate and the port was deserted. We may draw a picture of burned houses and roofless churches; of broken doors and narrow lanes, cumbered with useless plunder dragged from the houses and left in the streets because it could not be carried away; of dead bodies left unburied where they fell in defence or in flight along the streets and in the houses; of City gates lying open to any who chose to enter; of the City wall broken away, having never been repaired since the Britons fled before the Saxons came. This ruined and deserted city Alfred recovered. How? By a siege? What kind of siege would it be when there were no walls to defend; not enough men to man the walls, and not enough of the besiegers to attack them?

| From Strutt’s Sports and Pastimes. | From Luttrell’s Psalter. |

Does not the Chronicle answer these questions?

In A.D. 880. The “Army”—i.e. the Danes—“which had sat down at Fulham, went over sea to Ghent, and sat there one year.”

In A.D. 881. The “army went farther into France.”

In A.D. 882. “The army went far into France and there sat one year.”

In that year Alfred fought a sea-battle against “four Danish ships”—only four—took two, and received the surrender of the other two. But it was not with “four” ships that Cnut and Sweyn proposed to attack London.

In A.D. 883. “The army went up the Scheldt and sat there one year.”

This was the same year that Alfred “sat down against the army of London.”

The main body of the Danes was lying up the Scheldt; the Danish fleets were represented by four vessels; what kind of army was that before which Alfred sat down?

My own reading of the story is that the small force of Danes in, or near, London, retired without fighting, and that Alfred, meeting with no opposition, marched into the City and began at once, understanding the enormous advantage of possessing the place, to consider steps in order to secure that possession. He seems to have had a whole year during which he was left in peace, or comparative175 peace, in order to consider the position. Meantime, there was more fighting to be done before these measures could be fairly taken in hand. The Danes, retiring from London, divided into two parts: one division went into Essex; the other crossed the river and fell upon Rochester. Here Alfred met them and put them to flight; they escaped across the seas to their own country. Alfred’s fleet defeated the Danish fleet at the mouth of the Stour, but were themselves defeated in their turn.

The following year, 886, was again a year of peace, according to the Chronicle. The “Army” wintered in France near Paris. Alfred received the “submission of all the English except those who were under the bondage of the Danishmen.” This passage, if we were considering the history of the country, should set us thinking. In this place it is enough to note that Alfred took advantage of the respite to repair London. And he placed the City under the charge of Ethelred his son-in-law. So, whether by siege or by battle, or, as I rather believe, by the retirement of the enemy, Alfred recovered London, and, as soon as the condition of his affairs allowed, he repaired it and rebuilt it, and made it once more habitable and secure for the resort of merchants and the safeguarding of fugitives, of women, and of treasure.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content