Search london history from Roman times to modern day

161

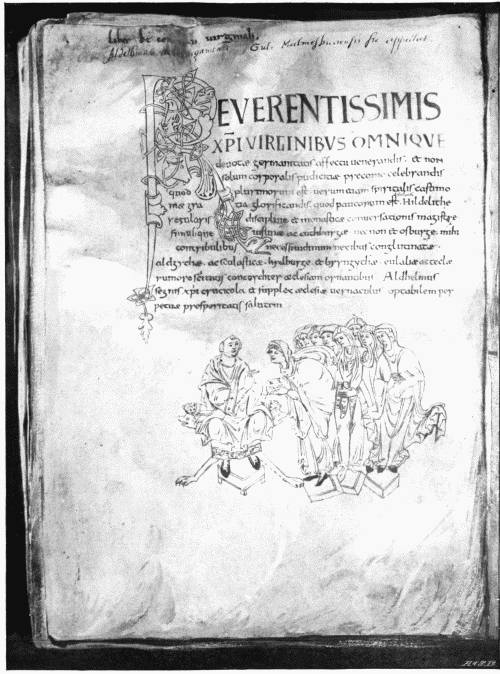

Let us return to the establishment of Christianity in London. It was in 604, as we have seen, that the East Saxons were baptized, their king, Sebert, being the nephew of Ethelbert, King of Kent, who was his overlord. It was Ethelbert, and not Sebert, who built St. Paul’s for Mellitus, the first Bishop of London. Christianity, however, is not implanted in the mind of man altogether by baptism. Mellitus was able to leave his diocese a few years after its creation in order to attend a synod at Rome, and to confer with the Pope on the affairs of the Church. This looks as if his infant Church was already in a healthy condition of stability. So long as Ethelbert lived, at least, there was the outward appearance of conformity; but when he died, in 616, his son Eadbald “refused to embrace the faith of Christ,” as Bede has it. Does this mean that he had not yet been baptized? In that case the “conversion” of the people can only mean the conversion of some among them. Perhaps, however, the words mean that he relapsed. In the next sentence we are told that his example was followed by many who, “under his father, had, either for favour, or through fear of the King, submitted to the laws of faith and chastity.” This king, Eadbald, took to wife his father’s widow—a crime for which, as the historian tells us, “he was troubled with frequent fits of madness, and was possessed by an evil spirit.”

However, his example was the signal for revolt. King Sebert died and was succeeded by his three sons, “still pagans.” Therefore the conversion of the East Saxons, at least, had not been complete. These princes “immediately began to profess idolatry, which during their father’s reign they had seemed a little to abandon”; they also granted liberty to the people to serve idols. Therefore the conversion had been by order of the King. The people, then, nothing loth, returned to their ancient gods and their old practices.

Some, however, remained faithful, and the services of the Church were still carried on at St. Paul’s, with sorrowful hearts.

We now chance upon a glimpse of the East Saxon mind, for the three princes,162 though they were no longer Christians, desired to get what they could for their own advantage out of the new religion. They observed that the most important part of the Christian ritual was the celebration of the Eucharist, in which the communicants received each a morsel of white bread. Clearly this was magic: the white bread was a charm: it protected those who received it from dangers of all kinds. They therefore called upon Mellitus to give them this charm, but without the profession of the Christian faith. In the words of Bede, they said, “Why do you not give us also that white bread, which you used to give to our father Saba (for so they used to call him), and which you still continue to give to the people in the church?” To whom he answered, “If you will be washed in that laver of salvation, in which your father was washed, you may also partake of the holy bread, of which he partook; but if you despise the laver of life, you may not receive the bread of life.” They replied, “We will not enter into that laver, because we do not know that we stand in need of it, and yet we will eat of that bread.” And being often earnestly admonished by him, that the same could not be done, nor any one admitted to partake of the sacred oblation without the holy cleansing, at last they said in anger, “If you will not comply with us in so small a matter as this, you shall not stay in our province”; and accordingly they obliged him and his followers to depart from their kingdom.

Mellitus, thus forced to abandon his work, retired to Canterbury, where he met Justus, Bishop of Rochester, also turned out of his diocese, and Laurentius, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was also meditating flight.

The two former resolved on passing over to France, there to await the event.

163

The three princes of the East Saxons, we are told, did not long survive their apostasy. For, marching out to battle with the West Saxons, they were all three slain and their army cut to pieces. Nevertheless, the people of London and Essex refused to acknowledge this correction and remained in their paganism.

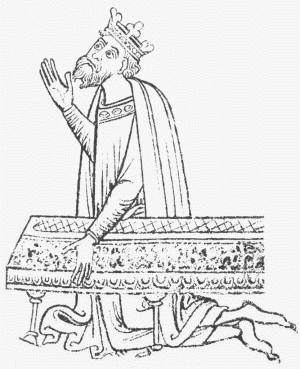

The story of Eadbald’s conversion and the restoration of Christianity to the kingdom of Kent is suspicious. It is as follows:—Laurentius, the Archbishop, appeared before the King one day, and taking off his shirt, showed his shoulders red and bleeding, as if with a grievous flagellation. He told the King that he had received this “Apostolical” scourging from St. Peter himself, as a punishment for thinking of deserting his flock. “Why,” asked the Apostle, “wouldest thou forsake the flock which I committed to you? To what shepherds wouldest thou commit Christ’s sheep which are in the midst of wolves? Hast thou forgotten my example, who, for the sake of those little ones, whom Christ recommended to me in token of His affection, underwent, at the hands of infidels and enemies of Christ, bonds, stripes, imprisonment, afflictions, and, lastly, the death of the cross, that I might at last be crowned with Him?”

King Eadbald accepted this miracle as a warning: he abjured the worship of idols, renounced his unlawful marriage, and embraced the faith of Christ. Laurentius, on this happy turn of events, sent for Mellitus and Justus to return. The latter was restored to his see of Rochester; the former, however, found his Londoners obstinate in their relapse. Unfortunately, Eadbald, the penitent, had not the same power that his father had enjoyed. It took nearly half a century to get Christianity firmly established in London.

About the year 635, thirty years after their defeat by the men of Wessex, the East Saxons returned to the faith. Their conversion was due in the first instance to the persuasion and arguments of Oswy, King of Northumbria, with his “friend”—as Bede calls him—his subject King, Sigebert of the East Saxons. When these arguments had prevailed, Sigebert, having been baptized, asked for priests to preach to his people. Cedda, afterwards Bishop of London, undertook the task, with such success that the whole people embraced Christianity. Again, however, they fell away, led by Sighere, one of the two Kings of the East Saxons. Their defection was caused by a pestilence, which was interpreted to mean the wrath of their former gods. It was in the year 665. The two Kings of the East Saxons were no longer “friends” of Northumbria, but of Mercia; and the King of the Mercians sent Jarumnan, Bishop of Lichfield, to bring the people back again. The Bishop was aided in his efforts by Osyth, queen of the apostate Sighere, afterwards known as St. Osyth. There was as little difficulty in securing a return as a relapse: Essex once more became Christian, and this time remained so. The missionary Bishop, Erkenwald, the Great Bishop, who remained in the memory of London until the Reformation, was the chief cause of the complete conversion of the people. He did not rest satisfied with the baptism of kings and thanes: he went himself among the rude and ignorant164 folk; he preached to the charcoal-burners of the forest and to the rustics of the clearing; he founded Religious Houses in the midst of the country people; he became, in life and after death, the protector of the people. He made it impossible for the old faith to be any longer regarded with regret. To the time of Erkenwald belong not only St. Osyth (her name survives in Size Lane) and St. Ethelburga, whose church is still standing beside Bishopsgate, but also St. Botolph, to whom five churches were dedicated.

St. Osyth was the mother of Offa, whose memory is preserved by Bede. He succeeded his father Sighere as one of the Kings of Essex, then subject to Mercia. He accompanied Coinred, King of the Mercians, ingoing to Rome, and in surrendering everything in order to become a monk.

Bede:—

“With him went the son of Sighere, King of the East Saxons above-mentioned, whose name was Offa, a youth of most lovely age and beauty, and most earnestly desired by all his nation to be their King. He, with like devotion, quitted his wife, lands, kindred, and country, for Christ and for the Gospel, that he might receive an hundredfold in this life, and in the world to come life everlasting. He also, when they came to the holy places at Rome, receiving the tonsure, and adopting a monastic life, attained the long-wished-for sight of the blessed apostles in heaven.” (Giles’s Trans. vol. iii. p. 237.)

His memory was preserved in London long after his death—even, indeed, until recent times—on account of this wonderful example of piety at first, and afterwards by the tradition which ascribed the site of St. Alban’s Church, Wood Street, in the City, to that of the chapel of King Offa’s palace. That tradition is gravely considered by Maitland, who decides against it. This Offa must not be confounded with the much greater Offa, King of the Mercians.

Documents relating to London are few in these centuries. The earliest notice of London among those collected and published in J. M. Kemble’sCodex Diplomaticus Aevi Saxonici, and in Benjamin Thorpe’sDiplomatarium, dates as far back as the year 695, if it is genuine; but it is said to be an early forgery. The document professes to be Bishop Erkenwald’s Charter of Barking Abbey. Reciting the lands given to the Abbey, it says, “Sexta juxta Lundoniam unius manentis data a Uulfhario rege. Septima supra vicum Lundoniae data Quoenguyda uxore.” What street is here intended? There is a deed by which Ethelbald, King of the Mercians, gives to165 Aldwulf, Bishop of Rochester, the right of sending one ship to the port of London without paying taxes or dues. It is dated 734.

In 734, King Ethelbald grants to the Bishop of Rochester leave to pass one ship without toll into the Port of London. In another charter the same King speaks of “Lundon tune’s hythe.” King Canulf of Mercia speaks of a Witenagemot in London—“loco praeclaro oppidoque regale.” In 833 there was another Council held in London by Egbert, presumably after his defeat at Charmouth.

The same King (743 or 745) allows to the venerable Bishop Mildred of Worcester all the rights and dues of two ships which may be demanded of them in the hythe of London town.

In the year 857, King Burgred of Mercia assigns to Bishop Alhune “aliquam parvam portionem libertatis, cum consensu consiliatorum meorum, gaziferi agelluli in vico Lundonioe: hoc est, ubi nominatur. Ceol-munding-chaga, qui est non longe from Westgetum positus.” Where was Ceol-munding-chaga? Where was Westgetum? And is the English preposition a mistake of Kemble’s?

In the year 889, “Alfred rex Anglorum et Saxonum et Aethelred sub regulus et patricius Merciorum ... Uuaerfrido, eximio Huicciorum antistiti, ad aecclesiam Weo-gernensem in Lundonia unam curtem quae verbotenus ad antiquum petrosum aedificium, id est, aet Hwaetmundes stane a civibus apellatur, a strata publica usque in murum ejusdem civitatis, cujus longitudo est perticarum xxvi et latitudo in superiori parte perticarum xiii et pedum vii et in inferiori loco perticarum xi et vi pedum, ad plenam libertatem infra totius rei sempiternaliter possidendum, in aecclesiasticum jus conscribimus et concedentes donamus.”

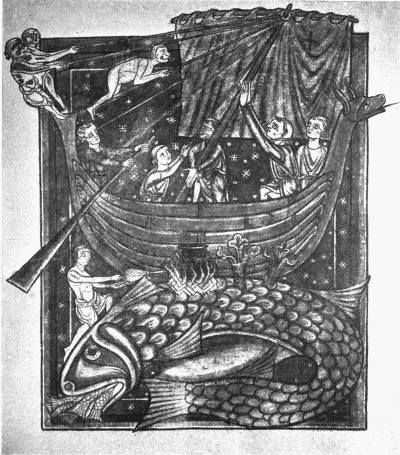

We have now arrived at the coming of the Danes. It seems a just retribution that the Saxons should in their turn suffer exactly the same miseries by robbery and murder as they had themselves inflicted upon the Britons. One knows not when the Northmen first tasted the fierce joy of piracy and marauding on the English coast; probably they began as soon as the farms and settlements of the English were worth plundering. It must be remembered that as yet there was little cohesion or joint action among the “kingdoms,” and that war was incessant between them. Read, for instance, the following passage from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It relates the wars of one year only, the year 823. Think of the condition of the country when all these battles and all this slaughter were crammed into one year only:—

166

“This year there was a battle between the Welsh and the men of Devon and Camelford; and the same year Egbert, King of the West Saxons, and Bernulf, King of the Mercians, fought at Wilton, and Egbert got the victory, and there was great slaughter made. He then sent from the army his son Ethelwulf, and Ealston his bishop, and Wulfherd his ealdorman, into Kent with a large force, and they drove Baldred the King northwards over the Thames. And the men of Kent, and the men of Surrey, and the South Saxons, and the East Saxons submitted to him; for formerly they had been unjustly forced from his kin. And the same year the King of the East Angles and the people sought the alliance and protection of King Egbert for dread of the Mercians; and the same year the East Angles slew Barnulf, King of Mercia.”

Attempts were made at combined action. In the year 833, for instance, as we have seen, King Egbert called a Witenagemot at London. This was attended by the King of Mercia and the bishops. The deliberations, however, of this Parliament did nothing to prevent the disasters that followed.

The share which fell to London of all the pillage and massacre was less than might have been expected. Thus, in 832 the Danes ravaged Sheppey; in 833 Dorsetshire. In 835 they were defeated in Cornwall; in 837 at Southampton and Portland; in 838 in Lindsey, in East Anglia, and in Kent. In 839 “there was great slaughter at London, at Canterbury, and at Rochester.” In 840 the Danes landed at Charmouth; in 845 at the mouth of the Parrett in Somersetshire; in 851 at Plymouth; in the same year the Saxons got some ships and met the enemy on the sea, taking nine ships and putting the rest to flight, but, which is significant, the Danes wintered that year on Thanet. “And the same year there came 350 ships to the mouth of the Thames, and the crews landed and took Canterbury and London by storm, and put to flight Berthwulf, King of the Mercians, with his army, and then went south over the Thames into Surrey.” King Ethelwulf with the men of Wessex met them at Ockley, and defeated them with great slaughter. In the same year the Saxons met them on the sea in ships and beat them off. They seem to have been driven out of the country by these reverses, for in 854 we read of battles fought in Thanet, which looks like an attempt to settle there again; and in 855 they succeeded in wintering on that island. In 860 they stormed and burned167 Winchester, and were then driven off by the men of Hampshire. In 865 they sat down in Thanet and made peace with the men of Kent for a price; but they broke their word. In 866 the Danes took up their winter quarters with the East Angles and made peace with them. In 867 there was fighting in Northumbria, the kings were slain, and the people made peace with the Danes; in 868 the Mercians made peace with them. In 870 the “army” marched into East Anglia from York and there defeated King Edmund (St. Edmund) and destroyed all the churches and the great and rich monastery of Medehamstede (Peterborough)—“at that time,” says the Chronicle, “the land was much distressed by frequent battles ... there was warfare and sorrow over England.” Both in 870 and in 871 there was fighting all the summer at and near Reading. In 872 “the army went from Reading to London and there took up their winter quarters”; in 874 they wintered at Repton; in 875 some marched north, and some south, wintering at Cambridge. In that year Alfred, now King, obtained a fleet and fought seven Danish ships successfully. In168 876 the Danes were at Wareham; in 877 their fleet was cast away and the army fled to the “fortress” of Exeter. In 878 there was fighting in the west country; in 879 the Danes were at Fulham on the Thames. Some of the Danes then crossed the Channel and visited France, leaving a part of the army in England. In 882 King Alfred fought them on the sea. The chronicle of 883 is brief, but extremely important: “That same year Sighelm and Athelstan carried to Rome the arms which the King had vowed to send thither, and also to India, to St. Thomas, and to St. Bartholomew, when they sat down against the army at London; and there, thanks be to God, they largely obtained the object of their prayer.”

If this brief chronicle be followed on the map, it will be perceived that, although fighting went on year after year in various parts of the country, London was in the grasp of the Danes for no more than twelve years. The area of the battlefield into which the Danes had converted England extended year by year, but always included London.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content