Search london history from Roman times to modern day

135

We now come to the period about which, so far as London is concerned, there are no historians and there is no tradition. Yet what happened may be read with certainty. The Roman legions were at last withdrawn. Britain was left to defend herself. She had to defend herself against the Saxon pirates in the east; against the Picts and Scots in the north; and against the wild tribes of the mountains in the west. Happily we have not in these pages to attempt the history of the two centuries of continual battle and struggle which followed before the English conquest brought at last a time of rest and partial peace. But we must ascertain, if we can, how London fared during the long interval.

Let us take the evidence (I.) of History; (II.) of Excavation; (III.) of Site; (IV.) of Tradition.

I. Of History.

For more than 200 years London is mentioned once, and once only, by any history of the time. The reference is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. “This year”—A.D. 457—“Hengist and Æsc his son fought against the Britons at the place called Cregan Ford, and there slew four thousand men; and the Britons then forsook Kent and in great terror fled to London.” They sought safety beyond the bridge and within the walls.

Otherwise there is a dead silence in the Chronicle about London. We hear about this place and that place being attacked and destroyed, but not London. Now, had there been any great battle followed by such a slaughter as that of Anderida, it must certainly have been mentioned. There never was any such battle. London decayed, melted away, was starved into solitude, but not into submission.

London was founded as a commercial port. We have seen that at first the trade of the country passed to the south over Thorney Island; but that, after the convenience of London had been discovered, it went to London. As a trading centre London was founded, and as a trading centre it continued. The people were always as they are now, traders. It was not the military capital; it was not, until late in the Roman occupation, the head-quarters of the civil administration. It flourished or it decayed, consequently, with the prosperity or the decline of trade.

The Saxons did not love walled cities; the defence of so long a136 wall—nearly three miles round—required a much larger army than the East Saxons could ever raise. And as yet the Saxons had not learned to trade. Besides, they loved open fields; walls they thought were put up for purposes of magic. “Fly! Fly! Avoid the place lest some wizard still lingering among the ruins should arise and exercise his spells. Back to the freedom and the open expanse of the fields!” Therefore, when the people of London went out and gradually disappeared, the Saxons were not moved to take their places.

If they came within sight of the grey walls of London they felt no inclination to enter; if out of curiosity they did enter, they speedily left the silent streets and ruined houses to the evil spirits and witches who lurked among them. The empty warehouses, the deserted quays, the wrecked villas, the fragments of the columns, seized for the building of the wall, the roofless rooms, spoke to them of a conquered people, but offered no inducement to settle down.

The Romano-British fleet was no more—it disappeared when the last Count of the Saxon Shore resigned his office; the narrow seas lay open to the pirates; the seas immediately began to swarm with pirates; the merchantmen, therefore, had to fight their way with doubtful success. This fact enormously increased the ordinary risks of trade.

The whole country was in continual disorder; there was no part of it where a man might live in peace save within the walls of a city. Rich farms were destroyed; the splendid villas were plundered and burned; orchards and vineyards were broken down and deserted; brigands and marauders were out on every road; wealthy families were reduced to poverty. What concerned London in all this was that there was no more demand for imports, and there were no more of the former exports sent up to be shipped. The way was closed for shipping, the highroads were closed, no more exports arrived, no more imports were wanted, trade therefore was dead.

II. The evidence of Excavation.

The whole of Roman London is lost, except for the foundations, some of which still lie underground. All the churches, temples, theatres, official buildings, palaces, and villas are all gone. They were lost when the Saxons took possession of the town. The names of the streets are gone—their very tradition has perished. The course of the streets is lost and forgotten. This fact alone proves beyond a doubt that the occupation of London was not continuous.21 The Roman gate of Bishopsgate lay some distance to the east of the Saxon gate; the Roman gate in Watling Street lay some distance to the north of the later Newgate; the line of the Ermin Street did not anywhere coincide exactly with the Roman road; the new Watling Street of the Saxons actually crossed the old one. We may note, also, 137that an ancient causeway lies under the tower of St. Mary le Bow. How can these facts be reconciled with the theory of continuous occupation? The Saxons, again, did not come in as conquerors and settle down among the conquered. They cannot have done so; otherwise they would have acquired and preserved something of Roman London. And though we should not, at this day, after so many years and so many fires, expect to find Roman villas standing, we should have some of the old streets with Roman or at least British names. All that is left to us, by tradition, of Roman London is its British name.

The destruction of a deserted city advances slowly at first, but always with acceleration. The woodwork of Roman London was carried off to build rude huts for the fisher-folk and the few slaves who stayed behind. They had at least their liberty, and lived on beside the deserted shore. The gentle action of rain and frost and sunshine contributed a never-ceasing process of disintegration; clogged watercourses undermined the foundations; trees sprang up amid the chambers and dropped their leaves and decayed and died; ivy pulled down the tiles and pushed between the bricks; new vegetation raised the level of the ground; the walls of the houses either fell or slowly disappeared. When, after a hundred years of desolation, the Saxon ventured to make his home within the ruined walls of the City, even if it were only to use the site after his manner at Silchester and Uriconium, as a place for the plough to be driven over and for the corn to grow, there was little indeed left of the splendour of the former Augusta.

Another argument in favour of the total desertion of London is derived from a consideration of the houses of a Roman city. The remains of Roman villas formed within the second and longer wall sufficiently prove that in all respects the city of Augusta was built in the same manner as other Roman cities; as Bordeaux, for instance, or Treves, or Marseilles. If, then, the conquerors had occupied London in the fifth century, they would have found, ready to their hand, hundreds of well-built and beautiful houses. It is true that the Saxon would not have cared for the pictures, statues, and works of art; but he would have perceived the enormous superiority of the buildings in material comfort over his own rude houses. It is absurd to suppose that any people, however fierce and savage, would prefer cold to warmth in a winter of ice and snow.

Again, it is not probable, not even possible, that in a city where such a construction was easy, owing to the lie of the ground, the Romans should have neglected to make a main sewer for the purpose for which the Cloaca Maxima was made, viz. to carry off the surface rainfall from the streets. Perhaps the Roman sewer may still be discovered. The outfall was certainly in the foreshore, between Walbrook and Mincing Lane; but the foreshore has long since been built upon and the sewer closed. It is reasonable to suppose that if the Saxons had found it they would have understood its manifold uses and would have maintained it.

138

It has pleased the antiquary to discover on the site of the Roman fort, or Citadel, the traces of the four broad streets at right angles which were commonly laid down in every Roman town. Indications of their arrangement, for instance, are still found at Dorchester, Chester, Lincoln, and other places. The antiquary may be right in his theory, but it must be acknowledged that the Roman streets in other parts of London have been built over and the old ways deflected. Surely if the Saxon occupation had taken place in the fifth century, the old arrangement of streets would have been retained on the simple principle that it entailed the least trouble.

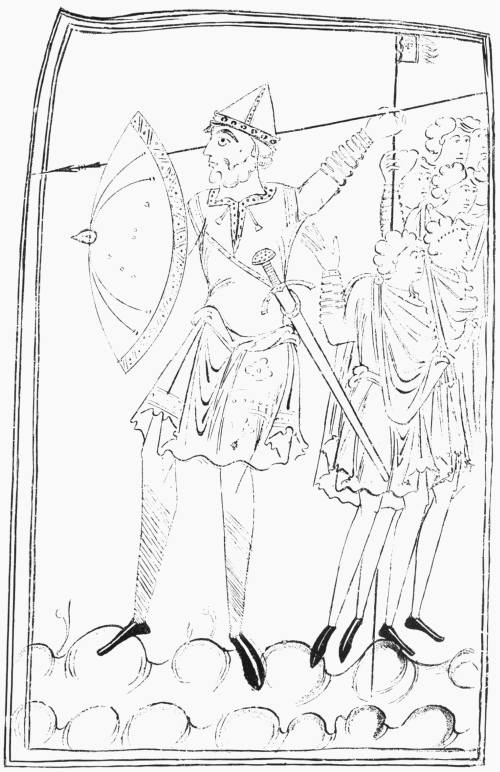

Consider, next, the Roman villa. “Their general plan is that of two or three courts open to the air, with open windows running round them, out of which lead small rooms of various kinds—the sleeping rooms and the women’s rooms generally being at the back, and the latter sometimes quite separated from the rest” (Hayter Lewis, Cities, Ancient and Mediæval). There is not in the accounts or pictures of any Anglo-Saxon house that we possess any similarity whatever to the Roman villa.139 If, however, the Saxon had occupied London in the fifth century, he would certainly have adopted the Roman house with its arrangements of separate rooms in preference to his own rude hall, in which all the household together slept on rushes round the central fire.

Again, had the Saxon occupied London in the fifth century, he would have found the houses provided with an apparatus for warming the rooms with hot air, both easy and simple, not at all likely to get out of gear, and intelligible to a child. Is it reasonable to suppose that he would have given up this arrangement in order to continue his own barbarous plan of making a great wasteful fire in the middle of the hall?

And he would have found pavements in the streets. Would he have taken them up and gone back to the primitive earth? Would he not rather have kept them in repair for his own convenience? And he would have found aqueducts and pipes for supplying conduits and private houses with water. Would he have destroyed them for mere mischief? One might mention the amphitheatre, which certainly stood outside the wall, but according to my opinion, as I have explained, the amphitheatre was destroyed in order to build the great wall, which was put up hurriedly and in a time of panic.

It may be objected that in later centuries the great house became somewhat like the Roman villa in being built round a court. The answer is that the mediæval court was not the Roman garden with a fountain and corridors; it was the place of exercise and drill for the castle. Even the country house built round its little court had its windows opening into the court, not looking out upon the country, thus showing something of a survival of the fortress. The mediæval court, of which so many instances are extant, belonged at first to the castle, and not to the villa.

III. The evidence of Site.

We must return to the position of London. We have seen that at the outset the City had in the north a wild and quaggy moor with an impenetrable forest beyond. On the east it had a marsh and a considerable stream flowing through that marsh; on the south a broad tidal river, and beyond that a vast marsh stretching a long way on both sides. On the west the City had a small stream in a marshy bed, and rising ground, which was probably in Roman times cleared and planted. Unlike any other town in the world, except Venice of later times, London had not an inch of land cultivated for her own food supplies, not a field for corn, not a meadow for hay, not an orchard or a vineyard or anything. She was dependent from the beginning, as she is still dependent, upon supplies brought in from the outside, except for the fish in the river. She was supplied by means of the Roman roads; by Watling Street and the Vicinal Road from Essex and from Kent; from the west by the highway of the Thames, and by ships that came up the Thames.

Now if a city wholly dependent upon trade experiences a total loss of trade,140 what must happen? First those who work for the merchants—the stevedores, lightermen, boatmen, porters, carriers, warehousemen, clerks, and accountants—are thrown out of work. They cannot be kept in idleness for ever. They must go—whither? To join the armies.

Next, the better class, the wealthier kind, the lawyers, priests, artists, there is no work for them. They too must go—whither? To the camp. Finally, when gold is no longer of any use because there is nothing to buy, the rich people themselves, with the officers of state, look round the decaying city and see no help for it but that they too must go. As for the slaves, they have long since broken away and fled; there was no longer any provision in the place; they had to go.

With bleeding hearts the rich men prepared to leave the place where they had been as luxurious as they could be in Rome itself when Rome was still at its best and proudest. They took with them only what each could carry. The tender girls carried household utensils, the boys carried arms, the parents carried the household gods—it is true that Christianity was the religion of the state, but their household gods had been in the house for long and had always hitherto brought good luck! Their sofas and tables, their rich plate and statues, their libraries, and their pictures, they left behind them; for these things could not be carried away. And so they went out through what their conquerors would in after-time call the New Gate, and by Watling Street, until they reached the city of Gloucester, where the girls remained to become the mothers and grandmothers of soldiers doomed to perish on the fields of disaster, and the boys went out to join the army and to fight until they fell. Thus was London left desolate and deserted. I suppose that a remnant remained, a few of the baser sort, who, finding themselves in charge of the City, closed the gates and then began to plunder. With the instinct of destruction they burned the houses after they had sacked them. Then, loaded with soft beds, cushions and pillows, and silk dresses, they sat down in their hovels. And what they did then and how they lived, and how they dropped back into a barbarism far worse than that from which they had sprung, we may leave to be imagined. The point is that London was absolutely deserted—as deserted as Baalbec or Tadmor in the wilderness,—and that she so continued for something like a hundred and fifty years.

How was the City resettled? Some dim memory of the past doubtless survived the long wars in the island and fifteen generations—allowing only ten years for a short-lived generation—of pirates who swept the seas. Merchants across the Channel learned that there were signs of returning peace, although the former civilisation was destroyed and everything had to be built up again. It must not be supposed, however, that the island was ever wholly cut off from the outer world. Ships crossed over once more, laden with such things as might tempt these Angles and Saxons—glittering armour, swords of fine temper, helmets and corslets. They found deserted quays and a city in ruins; perhaps a handful of savages cowering in141 huts along the river-side; the wooden bridge dilapidated, the wooden gates hanging on their hinges, the streets overgrown; the villas destroyed, either from mischief or for the sake of the wood. Think, if you can, of a city built almost entirely of wood, left to itself for a hundred and fifty years, or left with a few settlers like the Arabs in Palmyra, who would take for fuel all the wood they could find. As for the once lovely villa, the grass was growing over the pavement in the court; the beams of the roof had fallen in and crushed the mosaics in the chambers; yellow stonecrop and mosses and wild-flowers covered the low foundation walls; the network of warming pipes stood up stark and broken round the débris of the chambers which once they warmed. The forum, the theatre, the amphitheatre, the residence of that vir spectabilis the Vicarius, were all in ruins, fallen down to the foundations. So with the churches. So with the warehouses by the river-side. As for the walls of the first Citadel, the Prætorium, they, as we have seen, had long since been removed to build the new wall of the City. This wall remained unbroken, save where here and there some of the facing stones had fallen out, leaving the hard core exposed. The river side of it, with its water gates and its bridge gate, remained as well as the land side.

IV. The evidence of Tradition is negative.

Of Augusta, of Roman London, not a fragment except the wall and the bridge remained above ground; the very streets were for the most part obliterated; not a tradition was left; not a memory survived of a single institution, of an Imperial office or a custom. I do not know whether any attempt has been made to trace Roman influences and customs in Wales, whither the new conquerors did not penetrate. Such an inquiry remains to be made, and it would be interesting if we could find such survivals. Perhaps, however, there are no such traces; and we must not forget that until the departure of the Romans the wild men of the mountains were the irreconcilable enemies of the people of the plains. Did the Britons when they slowly retreated fall back into the arms of their old enemies? Not always. In many cases it has been proved that they took refuge in the woods and wild places, as in Surrey, and Sussex, and in the Fens, until such time as they were able to live among their conquerors.

The passing of Roman into Saxon London is a point of so much importance that I may be excused for dwelling upon it.

I have given reasons for believing—to my own mind, for proving—that Roman London, for a hundred years, lay desolate and deserted, save for the humble fisher-folk. In addition to the reasons thus laid down, let me adduce the evidence of Mr. J. R. Green. He shows that, by the earlier conquests of the Saxon invaders, the connection of London with the Continent and with the inland country was entirely broken off.142 “The Conquest of Kent had broken its communications with the Continent; and whatever trade might struggle from the southern coast through the Weald had been cut off by the Conquest of Sussex. That of the Gwent about Winchester closed the road to the south-west; while the capture of Cunetio interrupted all communication with the valley of the Severn. And now the occupation of Hertfordshire cut off the city from northern and central Britain.” We must also remember that the swarms of pirates at the mouth of the Thames cut off communication by sea. How could a trading city survive the destruction of her trade?

The Saxons, when they were able to settle down at or near London, did so outside the old Roman wall; they formed clearings and made settlements at certain points which are now the suburbs of London. The antiquity of Hampstead, for instance, is proved by the existence of two charters of the tenth century (see paper by Prof. Hales, London and Middlesex Archæological Transactions, vol. vi. p. 560).

I have desired in these pages not to be controversial. It is, however, necessary to recognise the existence of some who believe that London preserved certain Roman customs on which was founded the early municipal constitution of London, and that there was at the same time an undercurrent of Teutonic customs which did not become law. I beg, therefore, to present this view ably advocated by Mr. G. L. Gomme in the same volume (p. 528), for he is an authority whose opinion and arguments one would not willingly ignore.

His view is as follows:—

143

1. He does not recognise the desertion of London.

2. He does recognise the fact that the A.S. did not occupy the walled city.

3. That the new-comers had at first no knowledge of trade.

4. That they formed village settlements dotted all round London.

5. That the trade of London, when it revived, was not a trade in food, but in slaves, horses, metals, etc.

6. That the villages were self-supporting communities, which neither exported nor imported corn either to or from abroad, or to and from each other.

One would remark on this point that while London was deserted the villages around might very well support themselves; but with London a large and increasing city, the villages could not possibly support its people as well as their own. The city was provided from Essex, from Kent, from Surrey, and from the inland counties by means of the river.

7. That everywhere in England one finds the Teutonic system.

8. That in London the Teutonic customs encountered older customs which they could not destroy, and that these older customs were due for the most part to Roman influence.

Observe that this theory supposes the survival of Roman merchants and their descendants throughout the complete destruction of trade and the desertion of the City, according to my view; or the neglect of London and its trade for a century and more after the Saxon Conquest, according to the views of those who do not admit the desertion. Mr. Gomme quotes Joseph Story on the Conflict of Laws, where he argues that wherever the conquerors in the fall of Rome settled themselves, they allowed the people to preserve their municipal customs. Possibly; but every city must present an independent case for investigation. Now, according to my view there were no people left to preserve the memory of the Roman municipality. 22 9. That the A.S. introduced the village system, viz. the village tenure, the communal lands around, the common pasture-land beyond these.

10. That the broad open spaces on the north of London could not be used for agricultural purposes, and “they became the means of starting in London the wide-reaching powers of economical laws which proclaim that private ownership, not collective ownership, is the means for national prosperity.”

11. That the proprietors who became the aldermen of wards “followed without a break the model of the Roman citizen.”

This statement assumes, it will be seen, the whole theory of continued occupation; that is to say, continued trade, for without their trade the Roman citizens could not live.

144

12. That the existence of public lands can be proved by many instances recorded in the Liber Custumarum and elsewhere.

13. That the management of the public lands was in the hands of the citizens.

14. That the Folkmote never wholly dominated the city; nor was it ever recognised as the supreme council, which was in the hands of the nobles.

15. That the ancient Teutonic custom of setting up a stone as a sign was observed in London.

16. That there are many other Teutonic customs which are not represented in any collections of city law and customs.

17. That there are customs which may be recognised as of Roman origin, e.g. the custom of the Roman lawyers meeting their clients in the Forum. In London the sergeants-at-law met their clients in the nave of St. Paul’s.

Surely, however, there is nothing Roman about this. There was then no Westminster Hall; there were no Inns of Court; the lawyers must have found some place wherein to meet their clients. What place more suitable than the only great hall of the city, the nave of the Cathedral?

18. That there was a time when London was supported by her agriculture and not by her commerce.

As I said above, the settlements round London could not, certainly, support much more than themselves; and if we consider the common lands of the city—moorland and marsh-land with uncleared forest,—these could certainly do little or nothing for a large population.

19. That FitzStephen speaks of arable lands and pastures as well as gardens.

Undoubtedly he does. At the same time, we must read him with understanding. We know perfectly well the only place where these arable lands could exist, viz. a comparatively narrow belt on the west: on the north was moorland till we come to the scattered hamlets in the forest—chiefly, I am convinced, the settlements of woodcutters, charcoal-burners, hunters, and trappers; on the south were swamps; Westminster and its neighbourhood were swamps; the east side was covered, save for the scattered settlements of Stepney, by a dense forest with swamps on the south and east.

20. That the common lands of the city were alienated freely, as is shown by the Liber Albus.

21. That Henry I. granted to the citizens the same right to hunt in Middlesex as their ancestors enjoyed.

22. That this privilege “may have been drawn from the rights of the Roman burghers.”

It may; but this seems no proof that it was.

23. That the “territorium of Roman London determined the limits of the wood and forest rights of Saxon and later London.”

Perhaps; but there seems no proof.

145

It appears to me, to sum up, that these arguments are most inconclusive. It needed no Roman occupation to give the hunting people the right to hunt; nor did it need a Roman occupation to make the better sort attempt to assume the government; nor did it need the example of Rome for the lawyers to assemble in a public place; nor, again, need we go to Rome for the cause of the breaking up of an archaic system which had outlived its usefulness. If there were Roman laws or Roman customs in the early history of London—a theory which I am not prepared to admit—we must seek for their origin, not in a supposed survival of the Roman merchant through a century of desertion and ruin, but in Roman books and in written Roman laws.

Neither does the theory against the desertion of London seem borne out by the histories of Matthew of Westminster, Roger of Wendover, Nennius, Ethelwerd, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and Henry of Huntingdon. Let us examine into these statements, taking the latest first and working backwards.

I. Matthew of Westminster (circa 1320).

Matthew says that when the Romans finally left the island the Archbishop of London, named Guithelin (A.D. 435), went over to Lesser Britain, previously called Armorica, then peopled by Britons, and implored the help of Aldrœnus, fourth successor of King Conan, who gave them his brother Constantine and two thousand valiant men. Accordingly, Constantine crossed over, gathered an army, defeated the enemy, and became King of Britain. He married a lady of noble Roman descent, by whom he had three sons: Constans, whom he made a monk at Winchester; Aurelius and Uther Pendragon, who were educated by the Archbishop of London—presumably, therefore, in London.

In the year 445 Constantine was murdered. Vortigern, the “Consul of the Genvisei,” thereupon went to Winchester and took Constans from the cloister, and crowned him with his own hands, Guithelin being dead. The two brothers of Constans had been sent to Brittany.

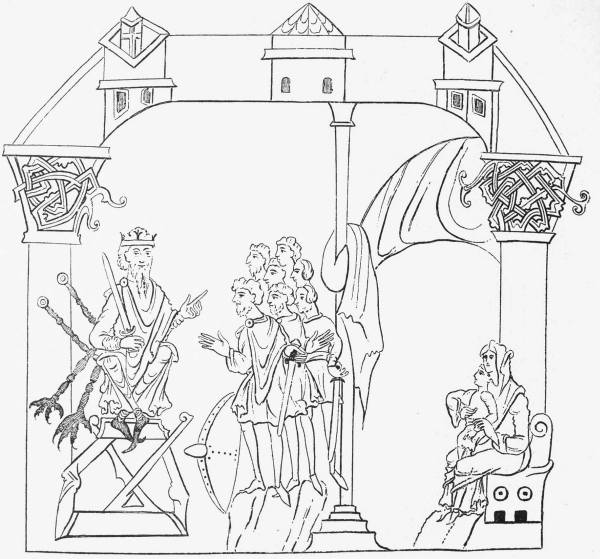

Vortigern then began to compass the destruction of the King, for his own purposes; he took the treasury into his own custody; he raised a bodyguard for the King of 100 Picts, whom he lavishly paid and maintained; he filled them with suspicions that if he were gone they would lose their pay. One evening, therefore, they rose—this bodyguard of Picts,—seized the King and beheaded him. This was in London. Vortigern, pretending great grief, called together the citizens of London and told them what had been done. As no one of the royal House was at hand, he elected himself and crowned himself King.

In 447 the country was overrun by Picts and Scots; there was also a famine followed by a pestilence. In 448 Germanus, a holy priest, led the Britons out to fight, and gave them a splendid victory over the enemy. But when Germanus went away the Picts and Scots came back again.

146

Vortigern invited the Saxons, the Angles, and the Jutes to come over and settle. They came; Hengist led them: they defeated the Picts and Scots: they invited more of their own people. Vortigern, who already had a wife and children, fell in love with Rowena, daughter of Hengist, and married her, to the disgust of the people.

Vortigern was deserted by the nobles, who made his son Vortimer King; but he was poisoned in the year 460 and died in London, where he was buried.

In 461 occurred the great slaughter of Britons by Hengist at Amesbury.

In 462, the Saxons imprisoned Vortigern until he gave up all his cities in ransom. They seized on London, York, Winchester, and Lincoln, destroying churches and murdering priests.

147

Then the Britons sent ambassadors to Brittany, entreating Aurelius and Uther Pendragon to come over.

The Prophecy of Merlin, which is attached to the year 465, is clearly a late production: it foretells, for instance—being wise after the event,—that the dignity of London shall be transferred to Canterbury; it also speaks of the gates of London, which are to be kept by a brazen man mounted on a brazen horse.

Aurelius, with his brother Uther Pendragon, came over from Brittany; they began by setting fire to the Citadel, in a tower of which Vortigern was lying, and so destroyed him.

In 473, Aurelius gained a great victory over Hengist. This was followed by other successes. The victories of Aurelius were frequent and overwhelming. Yet the Saxons, somehow, in spite of their decisive defeats, were strengthening and extending their hold rapidly and surely.

In 498, Aurelius died.

Uther Pendragon succeeded him and was crowned at Winchester. After another glorious victory Uther brought his prisoners to London, where he kept Easter exactly like a Norman king, surrounded by the nobles of the land.

In 516, Uther Pendragon, grown old and infirm, was poisoned at Verulam. His son Arthur succeeded him, being elected by Dubritius, Archbishop of London, and all the bishops and nobles of the land.

In 517, Arthur went out to besiege York, but was compelled to fall back upon London.

In 542, Arthur, after an unparalleled career of glory, died of his wounds in Avalon, and was succeeded by his cousin Constantine, who pursued the sons of Modred, and finding one concealed in a monastery of London, “put him to a cruel death.”

Under the date 585, London is mentioned as then being the capital of the kingdom of Essex.

In 586, Theonus, Archbishop of London, fled into Wales, seeing all the churches destroyed. He took with him those of the priests who had survived the massacres, and the sacred relics.

London, therefore, according to the story, was deserted, but not until the year 586.

In 596, Augustine landed on the Isle of Thanet and converted many.

In 600, the Pope sent the pallium to Augustine of London.

In 604, Mellitus was consecrated Bishop of London.

The writer then proceeds with the history as we have it in other chronicles.

II. Roger of Wendover (d. 1256).

A.D. 460. He says that Vortimer was buried in London.

462. Roger mentions London as one of the cities taken.

148

473. Roger mentions the great victory of Aurelius in Kent.

498. Roger makes the statement that Uther kept his Easter in London.

517. Arthur falls back upon London.

542. Constantine kills Modred’s son in London.

586. Flight of Theonus, Bishop of London.

It seems thus that Matthew of Westminster followed Roger of Wendover, who died A.D. 1237, so that even he wrote of these events 650 years after the alleged flight of the Bishop.

III. Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, who died some time in the latter half of the twelfth century—he was made Bishop of St. Asaph in 1152—provides the materials especially for the romance of King Arthur, for the story of King Lear, and other delightful inventions and traditions.

By Geoffrey we find it stated (1) that Vortimer was buried in London; (2) that the Saxons took London—A.D. 462 (?); that Aurelius, after his great victory, restored London, “which had not escaped the fury of the enemy”; that Uther Pendragon kept his Easter in London; that Arthur retired upon London; that Modred’s son seized upon London and Winchester; that Theonus was Archbishop of London; that Constantine captured one of Modred’s sons in a monastery of London; that Theonus fled from London with the surviving clergy.

IV. Nennius.

Nennius contains none of these statements or stories, but he says that Vortimer was buried in Lincoln.

V. Ethelwerd.

Ethelwerd says that in 457 the Britons, being defeated in a battle in Kent, “fled to London.” He says no more about London.

VI. Henry of Huntingdon (circa 1154).

He mentions the Battle of Creganford or Crayford, which, as we have already seen (p. 135), is recorded in the A.S. Chronicle, with the retreat to London. He makes no mention at all of London after that event till after the conversion and the arrival of Mellitus. Not a word is said about the events alleged by the later Chroniclers, while the great achievements of Arthur are shown to have been battles fought and victories won in the west country. Since, however, he mentions the massacre at Anderida, is it conceivable that he would have passed over any such event had it happened in London? And is it conceivable that, had London continued to be a city of trade and wealth, the Saxon would not have attacked it?

To sum up this evidence, we find that writers most nearly contemporary make no mention of London at all for a hundred and fifty years. We find Chroniclers six hundred years later mentioning certain events of no importance, and agreeing in149 the desertion of London, which they place about the year 586. The date signifies little, but the reference shows that there was certainly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries a tradition which pointed to a period of ruin and desertion. Geoffrey of Monmouth seems to have furnished most of the victories and great doings of the Britons, who were so victorious that they were continually driven back into the forests and into the mountains. When a traditional king succeeds, or holds his court, or dies, it is natural to provide him with a city, and there was London ready to hand. At the same time there was the tradition that at one time London was deserted. And so the whole matter is explained, and fits into the only working theory which accounts for the almost complete silence of the A.S. Chronicle as to the once great and glorious and wealthy city of Augusta.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content