Search london history from Roman times to modern day

112

The most important of all the Roman remains in London are the ruins of the wall.

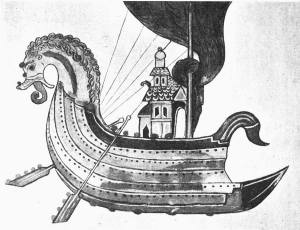

Under the protection of the Citadel the merchants first conducted their business; under its shadow the ships lay moored in the river, the bales lay on the quays, and the houses of the people, planted at first along the banks of the Walbrook, stretched out northwards to the moor and westwards as far as the river Fleet.

Then came the City wall.

It is strange that nothing should be said anywhere about so strong and important a piece of work as the wall. When was it built, and by whom? When was it destroyed, and by whom? Was it standing when the Saxons began their occupation? It appears not.

My theory is this:—According to the opinion of Sir William Tite, which now seems generally accepted (Archæologia, vol. xxxiii.), the wall of London—not the Citadel wall—was built somewhere about the year 360 A.D. There is no record of the building; yet it was a great and costly work. The date of the building is of some importance, because the wall itself was a sign of weakness. There was no need of such a wall in the second or third centuries: the Citadel and the power of the Roman name were enough. In the next century—a period of decay—this assistance failed, the inhabitants ceased to rely on the Roman name. Then they looked around. Augusta was a very large City; it had become rich; it was full of treasure; for want of a wall it might be taken at a rush. Moreover, not only was the Roman arm weakened, but the position of the City was far less secure than formerly. Of old the approaches were mere tracks through forest and over moor; now they were splendid roads. It was by means of these roads, constructed for the use of the legions, that the Picts and Scots were able to descend into the very heart of the country, even within a day or two of London; it was by these roads that the pirates from the east, landing in Essex, would some day swoop down upon the City. At the date suggested by Sir William Tite there was, one can see plainly, insecurity enough; though the people, from long habit, still relied on the legions and on the Roman peace. For nearly four hundred years, without113 any fighting of their own, the citizens had been safe, and had felt themselves safe. After the wholesale exportation of rebels from the Roman soldiery by Paulus Catena, when the invaders of the north came every day farther south and nearer London, it was borne in upon the citizens that the time of safety was over, that they must now defend themselves, and that the city of Augusta lay stretched out for a mile along the river and half a mile inland without a wall or any defence at all.

After the reprisals taken by Paulus Catena in 355 and his withdrawal, the country, nearly denuded of troops, lay open to invasion. But in the year 369 we have seen that Theodosius found the enemy ravaging the country round London, but they did not get in. The wall must have existed already. It was therefore between 355 and 369 that the wall was built. As I read history, it was built in a panic, all the people giving their aid, just as, in 1643, when there was a scare in the City because King Charles was reported to be marching upon it, all the people went out to fortify the avenues and approaches. Another reason for thinking114 this, apart from the general insecurity of the time, is the very significant fact that the wall is built not only with cut and squared stones, but with all kinds of material in fragments caught up from every quarter.

These fragments proclaim aloud that the construction of the wall was not a work resolved upon after careful consideration; that it was not taken in hand with the leisure due to so important a business; that the citizens could not wait for stone to be quarried and brought to London for the purpose; but that the wall was resolved upon, begun, and carried through with all the haste that such a work would allow, though with the thoroughness and strength which the Roman traditions enjoined.

In order to get stone enough for this great wall, the people not only sent to the quarries of Kent, whence came the “rag” and the sandstone, and to those of Sussex, where they obtained their chalk, but they also laid hands upon every building of stone within and without the City; they tore down the massive walls of the Citadel, leaving only the foundations; they used the walls and the columns and the statues of the forum and of the temple, and of all the official buildings; they took down the amphitheatre and used its stones; they even took the monuments from the cemeteries and built them up into the wall.

Fragments of pillars, altars, statues, capitals, and carved work of all kinds may be found embedded in the wall.

They took everything; and this fact is the chief reason why nothing of the Roman occupation—save the wall itself—remained above ground in Saxon times.

It is remarkable that the Roman walls of Sens, Dijon, Bordeaux, Bourges, Périgueux, and Narbonne are in the same way partly constructed of old materials, and that they contained the remains of temples, columns, pilasters, friezes, entablatures, sepulchral monuments, altars, and sculptures, all speaking of threatened danger, and the hasty building of a wall for which every piece of stone in the city was seized and used.

Attempts have been made to show that the wall was built in later times. Cemeteries, it is stated, have been found here and there. We have already seen that there were burials in Bow Lane, in Queen Street, Cheapside, in Cornhill, north of Lombard Street, on St. Dunstan’s Hill, in Camomile Street, and at St. Helen’s Church, Bishopsgate. Now interment within the city was forbidden by law. Hence it is inferred that the wall could not have been Roman work. The answer to this inference is very simple. The City of London was the enclosed town or fort on the eastern hillock; all these places of burial lie without the wall of this Citadel—that is to say, without the town.

As for the wall, so many portions of it remained until this century, so many fragments still remain, it is laid down with so much precision on the older maps, and especially on those of Agas and Wyngaerde, that it is perfectly easy to follow115 it along its whole course. For instance, there were standing, a hundred years ago, in the street called London Wall, west of All Hallows on the Wall, large portions of the wall overlooking Finsbury Circus, with trees growing upon them—a picturesque old ruin which it was a shame to destroy. This part of the wall is shown, with a postern, in the 1754 edition of Stow and Strype. Indeed that edition shows the whole course of the wall very clearly, still standing in its entirety.

Starting from the Tower, it ran in a straight line a little west of north-west to Aldgate; then it bent more to the west and ran in a curve to Bishopsgate; thence nearly in a straight line west by north to St. Giles’s Churchyard, where it turned south; at Aldersgate it ran west again as far as a little north of Newgate, where it turned south once more, crossed Ludgate Hill, and in ancient times reached the river a little to the east of the Fleet, leaving a corner, formerly a swampy bank of the Fleet, which was afterwards occupied by the Dominicans. Fragments of the wall still exist at All Hallows Church, at St. Alphege Churchyard, in St. Giles’s Churchyard, and at the Post Office, St. Martin’s-le-Grand, while excavations have laid bare portions in many other places. For instance, in the year 1852 there was uncovered, in the corner of some building, a very large piece of the wall at Tower Hill. By the exertions of Mr. C. Roach Smith this fragment was saved from destruction, examined carefully and figured. A plate showing that part of it where the ancient facing had been preserved is given in his Illustrations of Roman London. “Upon the foundation was placed a set-off row of large square stones; upon these, four layers of smaller stones, regularly and neatly cut; then a bonding course of three rows of red tiles, above which are six layers of stones separated, by a bonding course of tiles as before, from a third division of five layers of stones; the bonding course of tiles above these is composed of two rows of tiles; and in like manner the facing was carried to the top. The tiles of the third row are red and yellow; and they extend through the entire width of the wall, which is about 10 feet, the height having been apparently 30 feet. The core of the wall is cemented together with concrete, in which lime predominates, as is usual in Roman mortar. Pounded tile is also used in the mortar which cements the facing. This gives it that peculiar red hue which led FitzStephen to imagine the cement of the foundations of the Tower to have been tempered with the blood of beasts.” In the year 1763 there was still standing in Houndsditch part of a Roman tower. It is figured in Roach Smith’sRoman London. The drawing shows that the towers are as square as those still to be traced at Richborough. They were built solid at the bottom, hollow in the middle, and solid again at the top. The middle part contained a room with loopholes for the discharge of missiles and arrows. In the Houndsditch tower a window has taken the place of the loophole. According to FitzStephen, the wall was strengthened by towers at intervals. At the angles, as appears from the bastion in St. Giles’s Churchyard, the towers were circular.

116

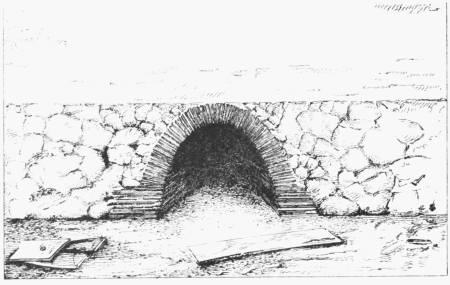

In 1857 excavations at the end of Aldermanbury laid open a remarkable portion of the wall; it was composed of a series of blind arches forming part of the solid masonry.

Nothing is left above ground of the Roman facing; what we see now is the old solid core with perhaps some of the mediæval facing. The uncovering of a large part of the wall at Aldersgate Street is thus described (Archæologia, vol. lii. 609):—

“The Government having determined to erect additional buildings to the General Post Office in St. Martin’s-le-Grand, certain steps were taken in order to ascertain the nature of the ground on which these buildings were to be placed. For this purpose, in the latter part of 1887, shafts were sunk along a line from Aldersgate Street to King Edward Street, some yards south of the old Money Order Office, and parallel to Bull and Mouth Street, a street now swept away. In sinking these pits the workmen came upon the Roman wall, and afterwards, as the process of preparing the site for the new buildings proceeded, a considerable fragment of it was unearthed running east and west, and extending from Aldersgate Street on the one side, to King Edward Street on the other. It was found that the line of buildings and walls forming the southern boundary of the churchyard of St. Botolph, Aldersgate Street, was based upon this wall, and it seems very probable that the churchyard and church above-named partly occupy the ground filling up the original ditch.

The portion of wall exposed, commencing near Aldersgate Street and running westwards, can be well seen for a length of upwards of 131 feet. A considerable length of this has been carefully underpinned, and, I am happy to say, will be preserved. The height remaining varies very considerably, but, measuring from the original ground level, at least eleven or twelve feet of masonry is still standing in places, not in any regular line at the top, but much broken into by the foundations of comparatively modern walls built upon it. Beyond the length named but little of the wall is to be seen, and as it approaches King Edward Street, just beneath the line of the houses in that street, on its eastern side, were discovered the foundations of a semicircular tower, or rather a tower semicircular in plan, with slightly prolonged straight sides. The foundations of this tower—and nothing but foundations remained—did not form any part of the structure of the Roman wall, but came with a butt-joint against it. They were 5 feet 3 inches wide, and composed of rubble-work of Kentish ragstone with some chalk, and a few fragments of old building materials bedded amongst the rubble. The internal measurements of this tower were 17 feet 3 inches by 16 feet, and the foundation of the Roman wall was seen to cross its base. The tower which stood on these foundations is probably an addition to the wall in the mediæval period. It was not Roman, and the foundations had no Roman character. Some pieces of worked stone discovered117 in them showed traces of Norman mouldings, and of foliage of the early English period. It is possible that the first tower west of Aldersgate, seen in Agas’s map of London 1560, may be the one the remains of which are here described.

Turning now to examine the construction of the Roman wall, it appears that it was built in the following manner:—A trench, from 10 feet 9 inches to 11 feet wide and 6 feet deep, was dug in the natural clay soil, the sides of the trench for a distance of 2 feet from the bottom sloping slightly outwards. The lower part of the trench for the depth of 2 feet was then filled in with puddled clay mixed with flints, and the whole well rammed down. Upon this came 4 feet of rubble foundation, lessening in some places to 2 feet, composed of masses of Kentish ragstone, laid in mortar, the larger pieces being placed with some care in the arrangement, so as to form a solid base for the superstructure of the wall itself.

This wall, between 8 and 9 feet thick, as far as could be ascertained, starts with a bonding course of three rows of tiles at the ancient ground level, which is 6 feet 9 inches below the level of Aldersgate Street. Above this course the body of the wall is composed throughout its height of masses of ragstone, with now and then a fragment of chalk bedded very roughly in mortar which has been pitched in, not run in, sometimes with so little care as to leave occasional empty spaces amongst the stones. The stones are often arranged in a rude herring-bone fashion, perhaps for greater convenience in packing them in, but the layers do not correspond in depth with the facing course.

The lowest band of tiles in the wall (at the ground level) is 8 inches high, and consists of three rows, the bed of mortar between them being often thicker than the tiles themselves. The vertical joints, however, are very close. The three bands of tiles above this lowest one are each 4½ inches high and of two rows. All these bands form bonding courses—layers, in fact, through the entire breadth of the wall, binding the rubble core together.

The tiles vary somewhat in size, but one perfect example which could be measured in every direction was 1 foot by 1 foot 4 inches, and from 1 inch to 1½ inches thick. They are set with their greatest length into the wall. Some yellowish tiles here and there form an exception to the great mass, which is red and well burnt.

The height of the spaces of stone facing between each band of bonding tiles is as follows:—The first space counting from the lowest band, 2 feet 4 inches; the second, 2 feet 4 inches; the third, 2 feet 5 inches; and the fourth, 2 feet 10 inches; though these last dimensions are somewhat doubtful, on account of the ruined condition of the upper part of the wall. Each of these spaces, with the exception of the ruined topmost one, of which little can be made out, is divided into five rows of facing stones, in regular rows, all apparently much the same height, though118 the individual stones vary considerably in length. These stones are very irregular in the amount of their penetration into the core of the wall, and there is nothing resembling the method adopted in working the facing stones of the wall of Hadrian, where each stone is cut to a long wedge shape and set with the pointer end into the wall. On the face the stones average from 4 to 5 inches in height, laid in a mortar bed of another inch or more in depth, and their average depth into the wall may be about 9 or 10 inches. They therefore form a mere skin between the tile bonding courses to the thick irregular rubble core. The stones have been brought to a clean face by splitting off their rough surface by the process known as pitching, and have been roughly squared in bed and joints with a hammer. The mortar employed seems to have nothing unusual in its composition. The mortar in which pounded tile forms so large an ingredient is not to be found here.”

In preparing for the new buildings erected, in the summer of 1857, on the north side of the gaol of Newgate, in the Old Bailey, and very near to the site of the City gate which gave its name to the prison, the ground was excavated to a considerable depth, and thus the foundation of the City wall was cut through, and many vestiges of old London were discovered. Among these, Mr. G. R. Corner, F.S.A., obtained a fragment of a mortarium, with the potter’s mark very clearly and distinctly impressed on the rim, but the words singularly disposed within a twisted border.

It is remarkable that a similar fragment, bearing the same mark, was also found in Newgate Street, on the 23rd October 1835, and is now preserved in Mr. Charles Roach Smith’s Museum of London Antiquities at the British Museum.

During the 1857 excavations, abundance of Roman bond-tiles and building materials appeared in and about the City wall; and Mr. Corner observed under a stratum of pounded brick, which was the foundation of a coarse pavement, a layer of burnt wood, the evident remains of a fire during, or previous, to the Roman period. Many feet higher was a similar layer of wood-ashes, produced by the Fire of 1666, or some similar occurrence in later times.

The following letter to Sir Christopher Wren from J. Woodward (June 23, 1707) gives a detailed account of certain excavations in Camomile Street:—

“In April last, upon the pulling down some old Houses, adjoining to Bishops-Gate, in Camomile Street, in order to the building there anew, and digging, to make Cellars, about four Foot under Ground, was discovered a Pavement, consisting of Diced bricks, the most red, but some few black, and others yellow; of nearly of a size, and very small, hardly any exceeding an inch in thickness. The extent of the Pavement in length was uncertain; it running from Bishopsgate for sixty feet, quite under the Foundation of some houses not yet pulled down. Its Breadth was about ten Feet; terminating on that side at the distance of three feet and a half from the City wall.119

Sinking downwards, under the Pavement, only rubbish occurred for about two foot; and then the workmen came to a Stratum of Clay; in which, at the Depth of two feet more, they found several urns. Some of them were become so tender and rotten that they easily crumbled and fell to pieces. As to those that had the Fortune better to escape the injuries of Time, and the Strokes of the Workmen that rais’d the Earth, they were of different Forms; but all of very handsome make and contrivance; as indeed most of the Roman Vessels we find ever are. Which is but one of the many instances that are at this day extant of the art of that people; of the great exactness of their genius, and happiness of their fancy. These Urns were of various sizes; the largest capable of holding full three gallons, the least somewhat above a Quart. All of these had, in them, ashes, and Cinders of burned Bones.

Along with the urns were found various other earthen Vessels: as a Simpulum, a Patera of very fine red earth, and a blewish Glass Viol of that sort that is commonly call’d a Lachrimatory. These were all broke by the Carelessness of the Workmen. There were likewise found several Beads, one or two Copper Rings; a Fibula of the same Metall, but much impaired and decayed; as also a Coin of Antoninus Pius, exhibiting on one side, the Head of that Emperor, with a radiated Crown on, and this inscription, ANTONINUS AVG ... IMP. XVI. On the reverse was the Figure of a Woman, sitting, and holding in her right hand a Patera; in her left an hastapura. The inscription on this side was wholly obliterated and gone.

At about the same depth with the things before mentioned but nearer to the City Wall, and without the Verge of the Pavement, was digg’d up an Human Skull, with several Bones, that were whole, and had not passed the Fire, as those in the Urns had. Mr. Stow makes mention of Bones found in like manner not far off this place, and likewise of Urns with Ashes in them; as do also Mr. Weever after him, and Mr. Camden.

The City Wall being, upon this occasion, to make way for these new buildings, broke up and beat to pieces, from Bishopsgate onwards, S. so far as they extend, an opportunity was given of observing the Fabrick and Composition of it. From the foundation, which lay eight Foot below the present surface, quite up to the Top, which was, in all, near Ten Foot, ’twas compil’d alternately of Layers of broad flat bricks; and of Rag Stone. The bricks lay in double ranges; and, each brick being but one inch and three-tenths in thickness, the whole layer, with the Mortar interpos’d, exceeded not three inches. The Layers of Stone were not quite two feet thick, of our measure. ’Tis probable they were intended for two of the Roman, their rule being somewhat shorter than ours. To this height the workmanship was after the Roman manner; and these were the Remains of the antient wall, supposed to be built by Constantine the Great. In this ’twas very observable that the Mortar was, as usually in the Roman Works, so very firm and hard, that the120 stone itself is easily broke, and gave way, as that. ’Twas thus far, from the Foundation upwards, nine Foot in Thickness, and yet so vast a bulk and strength had not been able to secure it from being beat down in former Ages, and near levell’d with the Ground.

The Broad thin Bricks, above mention’d, were all of Roman make; and of the very sort which, we learn from Pliny, were of common use among the Romans; being in Length a Foot and half, of their Standard, and in breadth a Foot. Measuring some of these very carefully, I found them 17 inches 4/10 in Length, 11 inches 6/10 in breadth, and 1 inch 3/10 in thickness of our Measure. This may afford some light towards the settling and adjusting the Dimensions of the Roman Foot; and shewing the Proportion that it bears to the English; a Thing of so great use, that one of the most accomplished and judicious writers of the last Century endeavour’d to compass it with a great deal of Travel and Pains. Indeed ’tis very remarkable, that the Foot-Rule follow’d up by the Makers of these Bricks was nearly the same with that exhibited on the Monument of Cossutius in the Colotian Gardens at Rome, which that admirable mathematician has, with great reason, pitched upon as the true Roman foot. Hence likewise appears, what indeed was very probable without this confirmation, that the standard foot in Rome was followed in the Colonies, and Provinces, to the very remotest parts of the Empire; and that too, quite down even to the Time of Constantine; in case this was the wall that was built by his appointment.

The old wall having been demolished, as has been intimated above, was afterwards repaired again, and carry’d up, of the same thickness, to eight or nine feet in height. Or if higher, there was no more of that work now standing. All this was apparently additional, and of a make later than the other part underneath. That was levell’d at top and brought to a Plane, in order to the raising this new Work upon it. The outside, or that towards the suburbs, was faced with a coarse sort of stone; not compil’d with any great care or skill, or disposed into a regular method. But, on the inside, there appear’d more marks of workmanship and Art. At the Bottom were five Layers, compos’d of Squares of Flint, and of Free-stone, tho’ they were not so in all parts, yet in some the squares were near equal, about five inches in Diameter; and ranged in a Quincunx order. Over these was a layer of brick; then of hew’n free-stone; and so alternately, brick and stone, to the top. There were of the bricks in all, six layers, each consisting only of a double course; except that which lay above all, in which there were four Courses of Bricks, where the layer was intire. These bricks were of the shape of those now in use; but much larger; being near 11 inches in length, 5 in breadth, and somewhat above 2½ in thickness. Of the stone there were five layers and each of equal thickness in all parts, for its whole length. The highest, and the lowest of these, were somewhat above a foot in thickness, the three middle layers each five inches. So that the whole height of121 this additional work was near nine foot. As to the interior parts or the main bulk of the wall, ’twas made up of Pieces of rubble-stone; with a few bricks, of the same sort of those us’d in the inner facing of the wall, laid uncertainly, as they happen’d to come to hand, and not in any stated method. There was not one of the broad thin Roman bricks, mentioned above, in all this part; nor was the mortar here near so hard as in that below. But, from the description, it may easily be recollected that this part, when first made, and intire, with so various and orderly a disposition of the Materials, Flint, Stone, Bricks, could not but carry a very elegant and handsome aspect. Whether this was done at the expense of the Barons, in the reign of K. John; or of the Citizens in the reign of K. Henry III.; or of K. Richard II.; or at what other time, I cannot take upon me to ascertain from accounts so defective and obscure, as are those which at this day remain of this affair. Upon the additional work, now described, was raised a wall wholly of brick; only that it terminating in battlements, these are top’d with Copings of Stone. ’Tis two feet four inches in thickness and somewhat above eight feet in height. The bricks of this are of the same Moduls, and size, with those of the Part underneath. How long they had been in use is uncertain. But there can be no doubt but this is the wall that was built in the year 1477 in the reign of King Edward IV. Mr. Stow informs us that that was compil’d of bricks made of clay got in Moorfields; and mentions two Coats of Arms fixt in it near Moorgate; one of which is extant to this day, tho’ the stone, whereon it was ingrav’d, be somewhat worn and defaced. Bishopsgate itself was built two years after this wall, in the form it still retains. The workmen lately employed there sunk considerably lower than the Foundations of this Gate; and, by that means, learned they lay not so deep as those of the old Roman Wall by four or five feet.”

“A portion of the ancient wall of London was discovered in Cooper’s Row, Crutched Friars, while preparing for the erection of a warehouse there. The length of this piece of wall is 106 feet 6 inches. The lower part is Roman, and the upper part mediæval. The latter consists of rubble, chalk, and flints, and is 17 feet 4 inches high to the foot face, which is 2 feet wide, and has a parapet or breast wall 5 feet high and 2 feet thick. It is much defaced by holes cut for the insertion of timbers of modern buildings, and is cased in parts with brickwork. On the west side are two semicircular arched recesses. This mediæval wall is set back and battered at the lower part on both sides, until it reaches the thickness of the Roman wall on which it is built. The Roman wall remains in its primitive state to a depth of 5 feet 7 inches, and in this part is faced with Kentish rag in courses, and has two double rows of tiles. The first course is 2 feet 8 inches from the top, and 4 inches thick. The second is 2 feet 2½ inches lower down, and 4½ inches thick. The tiles are from 1¼ inches to 1¾ inches thick, and of the size called sesquipedales, viz., a Roman foot wide, and 1½ feet long. They are laid, some lengthwise and others122 crosswise, as headers and stretchers. At the level of the upper course of tiles is a set-off of half a Roman foot. Below the second course the wall is cased with brickwork forming a modern vault, but at the foot of the brick casing a double row of Roman tiles is again visible 3 feet 9½ inches below the last-mentioned course, and these two courses are 4½ inches thick. These tiles come out to the face of the modern brickwork, which is about 5 inches in advance of the wall above it, so that there would seem to be a second set-off in the wall. One course of ragstone facing is seen below these tile-courses, but the excavation has not yet reached the foundation of the wall. The total height of Roman wall discovered is 10 feet 3 inches. The upper part of the Roman wall is 8 or 9 feet thick.” (L. and M. Arch. vol. iii. p. 52.)

In the autumn of 1874 were discovered the foundations of an old wall supposed to be those of the Roman wall. These remains were examined by Mr. J. E. Price, F.S.A., who thus described them:—

123

“The excavations were situate at the western end of Newgate Street, at the corner adjoining Giltspur Street, and at but a short distance from the site of the old ‘Compter,’ removed a few years since. The remains were first observed in clearing away the cellars of the houses which separated this building from Newgate Street and covered a considerable area. They were on the north side of the street, and appeared at a short distance from the surface. The City wall ran behind the houses, forming at this point an angle, whence it branched off beneath Christ’s Hospital in the direction of Aldersgate. Adjoining the wall was a long arched vault or passage, and upon the City side of this, a well, approached by a doorway leading to a flight of perhaps a dozen steps. This staircase was arched over, being covered by what is technically termed a bonnet arch. In addition, there were walls and cross walls several feet in thickness, all extremely massive, and with foundations of great strength and durability. These walls were chiefly composed of ragstone, oolite, chalk, and firestone, with an occasional brick or tile, and the vaulted passage of two rings of stonework formed by squared blocks of large dimensions. The width of the passage was from 7 to 8 feet, the stones composing the arch measuring from 2 to 3 feet wide, and nearly 2 feet high. The side walls of the passage were faced with carefully squared blocks laid in little, if any, mortar, and of immense size, some of them being from 4 to 5 feet long by 2 in height, and all such as would be selected in the construction of a building devoted to uses requiring more than ordinary strength. At the junction of the passage with the external wall, the outer facing of the arch was visible; it had been carefully worked, and upon it appeared a hollow chamfer of a decided mediæval type, a circumstance which alone strongly militates against the Roman theory. The mortar also was such as may be usually found in mediæval buildings, but presented none of the characteristics either of Roman mortar or Roman concrete. Nor were there any such unmistakable substances found attached to the tiles, the rubble, or the stonework which made up the section of the City wall. Roman mortar is not easily mistaken; so hard and so durable is it that it is frequently easier to break the stones themselves than the cement which holds them together. In the Roman walls found at the erection of the Cannon Street Railway Station, so solid was the masonry that it was with the greatest difficulty that sufficient could be removed for the introduction of the new brickwork, and much of that enormous building rests upon foundations such as no modern architect could improve.” (Arch. vol. v. pp. 404-405.)

Mr. Price concluded that the foundations thus disclosed were not Roman at all, but of much later date. He thought that they were the foundations of a gate and gaol erected after the Conquest. His view appears to be well founded. And yet the foundations may have been on the site of the Roman wall. He seems to have supposed that the Roman wall did not extend so far west and north, on account of the great area enclosed. But he does not state at what period this great area could have been more fitly enclosed. If we consider that a large part of the City consisted of gardens and villas, there is a reason for the enclosure; while the argument that the wall could not have been defended throughout its length is also met by the fact that it could not be easily attacked because of its length; that the scientific methods of sieges were not invented till much later; that in order to meet them the moat was constructed; and that the wall alone was sufficient for the assailants its builders had in view when it was first erected.

I must reserve the consideration of the mediæval gates for a later time. Meanwhile, it must be noted that neither the Bishopsgate nor Newgate of the later period stood upon the original Roman site.

The Roman foundations of Bishopsgate have been discovered in Camomile124 Street, south-east of the later Bishopsgate; and those of the old gate of Watling Street have been found north of the later Newgate.

There were fifteen bastions, according to Maitland. Of these there are shown on the maps three between the Tower and Aldgate, one at Cripplegate, two in Monkwell Street, one at Christ’s Hospital, and another near the corner of Giltspur Street, 100 feet from Newgate. On the occasion of a fire at Ludgate in 1792, portions of an ancient watch-tower were discovered.

Briefly, therefore, fragments of the wall can be seen on Tower Hill, where there is a splendid piece 250 feet long; at All Hallows on the Wall, where a part was taken down about 1800 in the street called London Wall; at St. Alphege Churchyard, at Cripplegate, and in the Old Bailey. Add to these the discoveries in Camomile Street in 1874, those in Bull and Mouth Street, in Giltspur Street, north of Christ’s Hospital, south of Ludgate, and the foundations in Thames Street.

Between Blackfriars and the Tower ran the old river-side wall. This had been pulled down before the reign of Henry II., but the foundations remain to this day, and have been uncovered in one place at least. The wall ran along the middle of Thames Street. The portion discovered was at the angle where the wall met the river at the foot of Lambeth Hill. It was when works connected with the sewage were being executed that the wall was found nine feet below the surface.

Mr. C. Roach Smith thus describes the finding of the river wall:—

125

“The workmen employed in excavating for sewerage in Upper Thames Street advanced without impediment from Blackfriars to the foot of Lambeth Hill, where they were obstructed by the remains of a wall of extraordinary strength, which formed an angle at Lambeth Hill and Thames Street. Upon this wall the contractor for the sewer was obliged to excavate to the depth of about 20 feet, and the consequent labour and delay afforded me an opportunity of examining the construction and course of the wall. The upper part was generally met with at the depth of about 9 feet from the level of the present street, and 6 from that which marks the period of the great fire of London, and, as the sewer was constructed to the depth of 20 feet, 8 feet of the wall in height had to be removed. In thickness it measured from 8 to 10 feet. It was built upon oaken piles, over which was laid a stratum of chalk and stone, and upon this a course of hewn sandstones, each measuring from 3 to 4 feet by 2 and 2½ feet, cemented with the well-known compound of quicklime, sand, and pounded tile. Upon this solid substructure was laid the body of the wall, formed of ragstone, flint, and lime, bonded at intervals with courses of plain and curved-edged tiles. This wall continued with occasional breaks, where at some remote time it had been broken down, from Lambeth Hill as far as Queenhithe. On a previous occasion I had noticed a wall precisely similar in character in Thames Street, opposite Queen Street.

One of the most remarkable features of this southern wall remains to be described. Many of the large stones which formed the lower part were sculptured and ornamented with mouldings denoting their use in the friezes or entablatures of edifices at some period antecedent to the construction of the wall. Fragments of sculptured marble, which had also decorated buildings, and part of the foliage and trellis-work of an altar or tomb, of good workmanship, had also been used as building materials. In this respect the wall resembles many of those of the ancient towns on the Continent, which were partly built out of the ruins of public edifices, of broken altars, sepulchral monuments, and such materials, proving their comparatively late origin, and showing that even the ancients did not at all times respect the memorials of their ancestors and predecessors, and that our modern vandalism sprang from an old stock.” (Illustrations of Roman London.)

On the reclaiming of the foreshore I have already (p. 105) given Sir William Tite’s evidence. I here return to the subject, which is closely connected with the river-side wall. Behind the river wall the gentle slope continued until the ground rose from 26 feet above the river to 50 feet. Now, if the theory which considers the dedicating of the churches here shows the extreme antiquity of the town is correct, this ought to have been the most densely populated part of the City in the fourth century. I do not know why it should have been so. The ports of Roman London were, as I have already advanced, two—Walbrook and Billingsgate: the first a natural port; the second an artificial port constructed for convenience close to Bridge Gate. There was no port along the south front of London between the Fleet and the Walbrook; there was no reason why this part should have been crowded. The wall was not built on the edge of the cliff (if there were a cliff) for very good reasons; the slope, more likely, was levelled for a space on both sides the wall. When, for instance, in King John’s reign, the town ditch was constructed, a ledge of 10 feet was left between the foot of the wall and the beginning of the slope of the moat. The same rule must have been observed in the construction of this wall.

This wall was constructed as far as Walbrook, where the stream and the banks were 230 feet wide. Here was the earliest port of London. What happened next is matter of conjecture, but it seems quite certain that the wall would end with a round bastion or tower protecting the entrance; that the mouth of the port was further protected by a stout chain capable of resisting the strongest ships; that within, on the banks of the stream, were many quays with vessels moored alongside; that on the opposite bank stood the west side of the Citadel, with its gate, whence, perhaps, we get the name of Dowgate.

The south wall of the Citadel, which extended as far as Mincing Lane,126 served as the river-side wall for that distance. It was continued from that point to the present site of the Tower—a distance of 450 yards—with a new wall. No remains, I believe, have yet been found of that last piece of work. Between the old river wall and the river is now a long and narrow strip of land of varying breadths, but generally 300 feet. It contains a series of parallel streets, narrow and short, running down to the water; these streets are now lined with tall warehouses, except in one or two places, where they still contain small houses for the residence of boatmen, lightermen, porters, and servants. The history of this strip of land is very curious. Remark that when the wall was built the whole foreshore lay below it without any quays or buildings on piles—a slope of grass above a stretch of mud at low water. The first port of London was Walbrook. Within the stream ships were moored and quays were built for the reception of the cargoes. During the Roman occupation there were no water-gates, no quays, and no ports west of Walbrook.

The Roman name of the second port, which was later called Billingsgate, is not known. Observe, however, that there was no necessity for a break in the wall at this place, because the port was only a few yards east of the first London Bridge with its bridge gate in the wall of the Citadel. A quay, then, was constructed on the foreshore between the port and the bridge. Everything, therefore, unloaded upon this quay was carried up to the head of the bridge, and through the bridge gate into London.

Later on, when the third port was constructed at Queenhithe, the builders must have made an opening in the wall. Now, at Walbrook, at Billingsgate,127 and at Queenhithe the same process went on. The people redeemed the foreshore under the wall by constructing quays and wharves; they carried this process farther out into the bed of the river, and they extended it east and west. At last, before the river wall was taken down as useless and cumbersome, the whole of this narrow strip, a mile long and 300 feet broad, had been reclaimed, and was filled with warehouses and thickly populated by the people of the port, watermen, stevedores, lightermen, boat-builders, makers of ships’ gear, sails, cordage, etc., with the eating-houses and taverns necessary for their wants.

This process, first of building upon piles, then of forming an embankment, was illustrated by the excavations conducted for the construction of London Bridge in 1825-35. There were found, one behind the other, three such lines of piles forming embankments. The earliest of these was at the south end of Crooked Lane; the second was 60 feet south of the first; the third was 200 feet farther south.

The sixteenth-century maps of London may also be consulted for the manner in which the quays were built out upon piles. It is obvious that more and more space would be required, and that it would become more and more necessary to conduct the business of loading and unloading at any time, regardless of tide.

These considerations strengthen the evidence of Sir William Tite and his opinion that the whole of the streets south of Thames Street must have been reclaimed from the foreshore of the bank by this process of building quays and creating water-gates for the convenience of trade.

The destruction of the wall, which had vanished so early as the twelfth century, is thus easily accounted for. Its purpose was gone. The long lines of quays and warehouses were themselves a sufficient protection. The people pulled down bits of it for their own convenience, and without interference; they ran passages through it and built against it.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content