Search london history from Roman times to modern day

95

If one stands in the Museum of the Guildhall and looks round upon the scanty remains of Roman London there exhibited, one feels a cold doubt as to the alleged wealth and greatness of the ancient city. Is this all that has to be shown after an occupation of nearly four hundred years? There is not much more: one may find a room at the British Museum devoted to this subject; and there are a few small private collections containing nothing of importance. Yet when we consider the length of time since Roman London fell; the long history of reconstruction, fire, and successive occupations; the fact that twice—once for more than a hundred years—London was entirely deserted, we must acknowledge that more remains of Roman London than might have been expected. What exists, for instance, of that other great Roman city now called Bordeaux? What, even, of Lutetia Parisiorum? What of Massilia, the most ancient of Gallic cities?

There are, however, many remains of Roman London which are not preserved in any collection. Some are above ground; some have been dug up and carried away; some have been disclosed, examined, sketched, and again covered up.

Antiquaries have been pleased to find traces of Roman relics of which no memory or tradition remains. Thus, we are assured that there was formerly a Campus Martius in London; its site is said to have been that of the Old Artillery Ground. A temple of Diana is said to have stood on the south side of St. Paul’s. There was a mysterious and extensive crypt called the Camera Dianæ, supposed to have been connected with the worship of that goddess; it was standing in the seventeenth century. Probably it was the crypt of some mediæval house. Stukeley persuaded himself that he found in Long Acre the “magnificent circus, or racecourse, founded by Eli, father of Casvelhun”; he also believed that he had found in Hedge Lane the survival of the agger or96 tumulus of King Eli’s grave. The same antiquary preferred to trace Julius Cæsar’s Camp in the Brill opposite old St. Pancras Church.

It is sometimes stated that excavations in London have been few and scattered over the whole area of the City; that there has been no systematic and scientific work carried on such as, for instance, was conducted, thirty years ago, at Jerusalem by Sir Charles Warren. But when we consider that there is no single house in the City which has not had half a dozen predecessors on the same site, whose foundations, therefore, have not been dug up over and over again, no one can form any estimate of the remains, Roman, British, and Saxon, which have been dug up, broken up, and carted away. During certain works at St. Mary Woolnoth, for instance, the men came upon vast remains of “rubbish,” consisting of broken pottery and other things, the whole of which were carried off to St. George’s Fields to mend or make the roads there. The only protection of the Roman remains, so long as there was no watch kept over the workmen, lay in the fact that the Roman level was in many places too deep for the ordinary foundations. Thus in Cheapside it was 18 feet below the present surface; in other places it was even more.

The collection of Roman antiquities seems to have been first undertaken by John Conyers, an apothecary, at the time of the Great Fire. The rebuilding of the City caused much digging for foundations, in the course of which a great many Roman things were brought to light. Most of these were unheeded. Conyers, however, collected many specimens, which were afterwards bought by Dr. John Woodward. After his death part of the collection was bought by the University of Cambridge; the rest was sold by auction “at Mr. Cooper’s in the Great Piazza, Covent Garden.” Three other early collectors were John Harwood, D.C.L.; John Bagford, a bookseller, who seems to have had some knowledge of coins; and Mr. Kemp, whose collection contained a few London things, especially the two terra-cotta lamps found on the site of St. Paul’s, which were supposed to prove the existence of a temple of Diana at that spot.

Burial-places and tombs have been unearthed in various parts of the City, but all outside the walls of the Roman fortress. Thus, they have been found on the site of St. Paul’s, in Bow Lane, Queen Street, Cornhill, St. Dunstan’s Hill, near Carpenter’s Hall, in Camomile Street near the west end of St. Helen’s Church, in King’s Street and Ken Street, Southwark—outside Bishopsgate in “Lollesworth,” afterwards called Spitalfields. The last named was the most extensive of the ancient cemeteries.

Stow thus describes it:—

“On the East Side of this Churchyard lyeth a large Field, of old time called Lolesworth, now Spittlefield, which about the Year 1576 was broken up for Clay to make Brick: In the digging whereof many earthen Pots called Urnæ were found full of Ashes, and burnt Bones of Men, to wit of the Romans that inhabited here.97 For it was the custom of the Romans, to burn their Dead, to put their Ashes in an Urn, and then to bury the same with certain Ceremonies, in some Field appointed for that purpose near unto their City.

Every of these pots had in them (with the Ashes of the Dead) one Piece of Copper Money, with the Inscription of the Emperour then reigning: Some of them were of Claudius, some of Vespasian, some of Nero, of Antoninus Pius, of Trajanus, and others. Besides those Urns, many other pots were found in the same place, made of a white Earth, with long Necks and Handles, like to our Stone Jugs: these were empty, but seemed to be buried full of some liquid Matter, long since consumed and soaked through. For there were found divers Phials, and other fashioned Glasses, some most cunningly wrought, such as I have not seen the like, and some of Crystal, all which had Water in them, nothing differing in clearness, taste, or savour from common Spring Water, whatsoever it was at the first. Some of these Glasses had Oil in them very thick, and earthy in savour. Some were supposed to have Balm in them, but had lost the Virtue: Many of these Pots and Glasses were broken in cutting of the Clay, so that few were taken up whole.98

There were also found divers dishes and cups of a fine red coloured Earth, which shewed outwardly such a shining smoothness, as if they had been of Coral. Those had (in the bottoms) Roman Letters printed, there were also Lamps of white Earth, and red artificially wrought with divers Antiques about them, some three or four Images, made of white earth, about a Span long each of them: One I remember was of Pallas, the rest I have forgotten. I myself have reserved (amongst divers of those Antiquities there found) one Urna, with the Ashes and Bones, and one Pot of white Earth very small, not exceeding the quantity of a quarter of a Wine Pint, made in shape of a Hare, squatted upon her Legs, and between her Ears is the mouth of the pot.

There hath also been found (in the same Field) divers Coffins of Stone, containing the Bones of Men: These I suppose to be the Burials of some special Persons, in time of the Britons, or Saxons, after the Romans had left to govern here. Moreover, there were also found the Skulls and Bones of Men, without Coffins, or rather whose Coffins (being of great Timber) were consumed.” (Strype, vol. i. bk. ii. chap. vi.)

The description of all the Roman remains found in London would take too long. Let us, however, mention some of the more important (see App. III.).

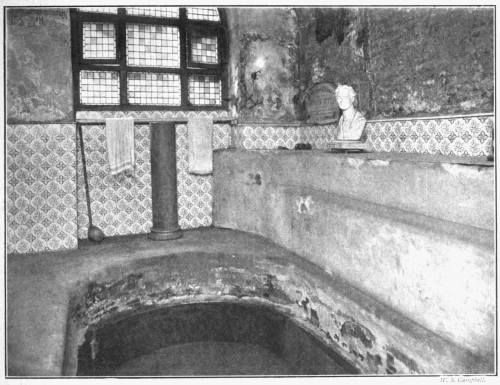

An undoubted piece of Roman work is the old bath still existing in Strand Lane. This bath is too small for public use: it belonged to a private house, built outside London, on the slope of the low hill, then a grassy field, traversed by half a dozen tiny streams. The bath has been often pictured.

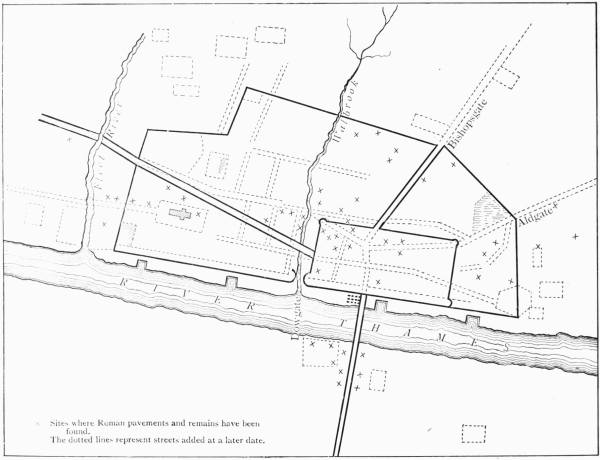

Many pavements, some of great length and breadth, have been discovered below the surface: of these some have been taken up; some have been drawn. More than forty pavements have been found north of the Thames. These were nearly all on the eastern side of the Walbrook, that side which has always been marked out as the original Roman settlement, and many of them were found within the assumed boundaries of the Roman Prætorium.19

Roman remains have been found under the Tower of Mary-le-Bow Church, where there was a Roman causeway; in Crooked Lane, in Clement’s Lane, in King William Street, in Lombard Street, in Warwick Square, on the site of Leadenhall Market, all along the High Street, Borough as far as St. George’s Church, in Threadneedle Street, Leadenhall Street, Fenchurch Street, Birchin Lane, Lime Street, Lothbury, Gracechurch Street, Eastcheap, Queen Street, Paternoster Row, Bishopsgate Street Within, and many other places.

Inscribed stones have also been found in Church Street, Whitechapel, in the99 Tenter Ground, Goodman’s Fields, Minories, in the Tower of London, at London Wall near Finsbury Circus, in Playhouse Yard, Blackfriars, at Pentonville, on Tower Hill, in Nicholas Lane, Lombard Street, in Hart Street, Crutched Friars.

A figure of a youth carrying a bow was found at Bevis Marks. A small altar was dug up in making excavations for Goldsmiths’ Hall.

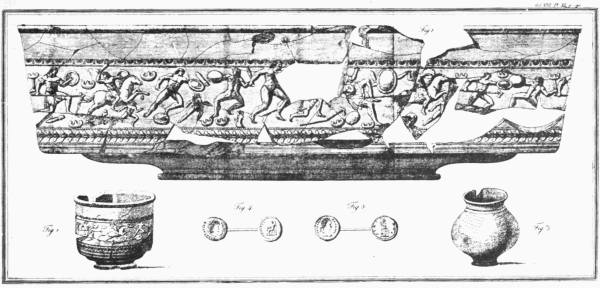

A large number of objects were found in 1837 by dredging the Thames near London Bridge. They were engraved by the Society of Antiquaries, and published by Mr. C. Roach Smith in his Illustrations of Roman London.

Among other objects which he has used in illustration of his book are pottery, lamps, bronzes, glass, coins, and utensils of various kinds.

A very interesting figure was discovered in Queen Street in 1842. It is described by Mr. W. Chaffers in Archæologia, vol. xxx. p. 543:—

“While watching the progress of the excavations recently made in Queen Street, Cheapside (for the formation of a sewer), I was fortunately enabled to obtain possession of several rare and curious specimens of Roman art. A short distance from Watling Street, a fine piece of Roman wall, running directly across the street, was exposed to view in a remarkably perfect condition, built of flat red tiles embedded in solid and compact mortar. Several others, lower down the street, were also discovered. Within a few yards of the wall, one of the bricklayers, removing some earth, struck his trowel against something which he conjectured to be a brass tap; but, on clearing further, he found it was the right heel of the figure, which lay upon its face. The height of the figure, if standing erect, would be 15 inches; but in its stooping posture, the perpendicular height from the base to the crown of the head is only 11 inches. It is evidently intended to represent a person in the attitude of shooting an arrow from a bow. The bow and arrow were probably of richer metal than the figure itself; but no vestiges of them were discovered. The aperture for the bow is seen in the closed left hand, which held it, and the bent fingers of the right appear in the act of drawing the arrow to its full extent previous to its evolation. The eyes are of silver, with the pupils open; the hair disposed in graceful curls on the head, as well as on the chin and upper lip. The left hand, which grasped the bow and sustained the arrow, is so placed as to bring the latter to a level with the eye; and the steadfast look and determined expression of the whole face are much heightened by the silver eyes. It was found at about the depth of between twelve and thirteen feet.”

In 1825 a small silver figure of Harpocrates was found in the Thames. It is now in the British Museum.

“Early in December 1877 considerable excavations were made at Pie Corner,20 over a space about a 100 feet long and 40 feet broad. At a depth of 11 feet, and at a spot 150 feet, measuring along the houses, from the middle of the great100 gateway of the hospital, the workmen came upon what they took for two great blocks of stone, which lay half inside the front line of the new building and half under the footway of the street. Continuing their excavation they found that the stones were two great coffins lying side by side, close together. A piece was broken off the lid of each, and in this state, before their contents had been disturbed at all, they were seen by Dr. Dyce Duckworth. In the southern sarcophagus was a leaden case containing a woman’s skeleton. This was disturbed hastily, the workmen being anxious to secure the lead. The other sarcophagus contained two skeletons, a man’s and a woman’s. As these had been somewhat displaced when I saw them half an hour later, I will quote a note which Dr. Duckworth has kindly written to me as to their exact position—‘The female faced west (the mediæval ecclesiastical position), the male faced east (layman’s position).’ The sarcophagi lay very nearly, but not precisely, east and west.”

A great many Roman remains were found in 1840 on digging for the foundations of the new Royal Exchange. On the east side of the area there were fragments showing that older buildings had been taken away. In the middle there were found thirty-two cesspools, in some of which were ancient objects. These were cleared out and filled up with concrete. The soil consisted of vegetable earth, accumulation and broken remains of various kinds with gravel at the depth of 16 feet 6 inches. At the western end, however, the workmen came upon the remains of a small building in situ resting on the gravel. The walls of the Old Exchange stood upon this building. When it ceased, oak piles had been driven down and sleepers laid upon the heads of these piles; a rubble wall was discovered below the piles, and under the wall was an ancient pit, sunk 13 feet through the gravel down to the clay.

“The pit was irregular in shape, but it measured about 50 feet from north to south, and 34 from east to west, and was filled with hardened mud, in which were contained considerable quantities of animal and vegetable remains, apparently the discarded refuse of the inhabitants of the vicinity. In the same depository were also found very numerous fragments of the red Roman pottery, usually called Samian ware, pieces of glass vessels, broken terra-cotta lamps, parts of amphoræ, mortaria, and other articles made of earth, and all the rubbish which might naturally become accumulated in a pond in the course of years. In this mass likewise occurred a number of Imperial Roman coins, several bronze and iron styles, parts of writing-tables, a bather’s strigil, a large quantity of caliga-soles, sandals, and remains of leather.” (Sir William Tite.)

The objects taken out of this pit are catalogued and described by Tite in his volume called Antiquities discovered in Excavating for the Foundations of the New Royal Exchange.

Roman pottery, found in Ivy Lane and in St. Paul’s Churchyard, was exhibited at the evening meeting of the L. and Midd. Arch. Soc., Sept. 18, 1860.

101

Roman keys have been found near St. Swithin’s Church, Cannon Street, at Charing Cross beside the statue of Charles I., beneath Gerard’s Hall Crypt, and in the Crypt of St. Paul’s while preparing for the interment of the Duke of Wellington.

102

“An important discovery was made in the year 1835 on the Coleman Street side near the public-house called the Swan’s Nest; here was laid open a pit or well containing a store of earthen vessels of various patterns and capacities. This well had been carefully planked over with thick boards, and at first exhibited no signs of containing anything besides the native gravelly soil, but at a considerable depth other contents were revealed. The vases were placed on their sides longitudinally, and presented the appearance of having been regularly packed or embedded in the mud or sand, which had settled so closely round them that a great number were broken or damaged in being extricated. But those preserved entire, or nearly so, are of the same material as the handles, necks, and pieces of the light-brown coloured vessels met with in such profusion throughout the Roman level in London. Some are of a darker clay approaching to a bluish black, with borders of reticulated work running round the upper part, and one of a singularly elegant form is of a pale-bluish colour with a broad black border at the bottom. Some are without handles, others have either one or two. Their capacity for liquids may be stated as varying from one quart to two gallons, though some that were broken were of much larger dimensions. A small Samian patera, with the ivy-leaf border, and a few figured pieces of the same, were found near the bottom of this well, and also a small brass coin of Allectus, with reverse of the galley, Virtus Aug., and moreover two iron implements resembling a boat-hook and a bucket-handle. The latter of these carries such a homely and modern look, that, had I no further evidence of its history than the mere assurance of the excavators, I should have instantly rejected it, from suspicion of its having been brought to the spot to be palmed off on the unwary; but the fact of these articles being disinterred in the presence of a trustworthy person in my employ disarms all doubt of their authenticity. The dimensions of the pit or well were about 2 feet 9 inches or 3 feet square, and it was boarded on each side with narrow planks about 2 feet long, and 1½ to 2 inches thick, placed upright, but which framework was discontinued towards the bottom of the pit, which merged from a square into an oval form.” (C. Roach Smith in Archæologia, vol. xxix.)

The following is a list of the more important tessellated pavements which have been discovered in the City:—

103

| 1661. | In Scot’s Yard, Bush Lane, with the remains of a large building. This is supposed to have been an official residence in the Prætorium. Sent to Gresham College. |

| 1681. | Near St. Andrew’s, Holborn—deep down. |

| ” | Bush Lane, Cannon Street—deep down. |

| 1707. | In Camomile Street—5 feet below the surface, with stone walls. |

| 1785, | 1786. Sherborne Lane. Four pavements were found here. |

| 1786. | Birchin Lane, with remains of walls and pottery, at depth of 9 feet, 12 feet, and 13 feet. |

| 1787. | Northumberland Avenue and Crutched Friars—12 feet deep. Society of Antiquaries. |

| 1792. | At Poulett House, behind the Navy Pay Office, Great Winchester Street. |

| 1794. | Pancras Lane—11 feet deep. |

| 1803. | Leadenhall Street—at depth of 9 feet 6 inches. British Museum. |

| 1805. | Bank of England, the north-west corner. British Museum. |

| 1805. | St. Clement’s Church. |

| 1835. | Bank of England, opposite Founders’ Court, and St. Margaret, Lothbury. |

| 1836. | Crosby Square—40 feet long, and 12 feet 1 inch deep. |

| 1839. | Bishopsgate Within. |

| 1840. | Excise Office Yard, Bishopsgate Street—13 feet deep. |

| 1841. | The French Protestant Church, Threadneedle Street—14 feet 2 inches deep. |

| Two other pavements also found in this street. | |

| ” | West of the Royal Exchange—at the depth of 16 feet 6 inches. |

| ” | Paternoster Row. |

| ” | Sherborne Lane, with amphoræ, etc. 104 |

| 1843. | Wood Street. |

| ” | King’s Arms Yard, Moorgate Street. |

| ” | Coleman Street—buildings at a depth of 20 feet, with pottery, sandals, etc. |

| ” | M. Garnet’s, Fenchurch Street. |

| 1844. | Threadneedle Street, near Merchant Taylors’ Hall—at depth of 12 feet. |

| 1847. | Threadneedle Street, with the hypocaust and foundation of a house. |

| 1848. | Coal Exchange—at depth of 12 feet. Baths or villa with mosaic. |

| 1854. | The Old Excise Office, Old Broad Street—at the depth of 13 feet. |

| ” | Bishopsgate Street—at the depth of 13 feet. |

| 1857. | Birchin Lane. |

| 1859. | Fenchurch Street, opposite Cullum Street—11 feet 6 inches deep. |

| ” | On the site of Honey Lane Market, while making trenches for new walls, at a depth of 17 feet the workmen came upon a tessellated pavement; the portion uncovered was 6 or 7 feet long, and 4 feet wide. Some 30 feet north of this pavement, and adjoining a spring of clear water, was found a thick wall which had the appearance of a Roman wall. In the earth were found many skulls and human bones. |

| ” | Paternoster Row—40 feet long. |

| ” | East India House—19 feet 6 inches deep. Another pavement found here. |

| 1864. | Paternoster Row—9 feet 6 inches deep. |

| ” | St. Paul’s Churchyard—18 feet deep. |

| 1867. | Union Bank of London, St. Mildred’s Court. |

| 1869. | Poultry. |

| ” | Tottenham Yard. |

| ” | Lothbury. |

| ” | Bush Lane. |

| ” | S.E. Railway Terminus. |

| ” | Cornhill, with the foundations of walls. |

| ” | Bucklersbury—19 feet deep. |

| 1867-1871. | Queen Victoria Street. Roman pavement in the middle of the roadway, Mansion House end. Close beside the pavement was found an ancient well, and a passage ran between. |

The things that have been found are all pagan: pottery with the well-known Roman figures upon it, figures certainly not Christian; statues and statuettes of Harpocrates, Atys, Mercury, Apollo, the Deæ Matres; tessellated pavements of which the figures and designs contain no reference to Christianity.

As we have seen, tiles have been found inscribed with the letters PRB. Lon. or PRBR. Lon. (see p. 74).

105

It is on symbolical monuments that we expect to find evidence of the religion of a people. It is therefore strange that in Roman London, where undoubtedly Christianity was planted very early, we find no trace of the Christian religion. Gildas, who is supposed to have lived in the latter part of the sixth century, refers to the first preaching of Christianity as having taken place soon after the defeat of Boadicea, but reliance cannot be placed on the few historical statements which we find in the midst of his ravings; and he says that the Church was spread all over the country, with churches and altars, the three orders of priesthood, and monasteries. The persecution of Diocletian was felt in Britannia, where there were many martyrs, with the destruction of the churches, and a great falling from the faith. When the persecutions ceased, Gildas goes on, the churches were rebuilt. Tertullian says in A.D. 208, “Britannica inaccessa Romanis loca, Christo vero subdita.” At the Council of Arles, A.D. 314, as we have seen, three British Bishops were present. At later councils British Bishops were always present. Yet no ruins remain in London of a Roman British Church. No monuments, no literature, no traditions remain; only here and there a word—here and there a monogram.

In the year 1813, in the excavations made for the new Custom-House, three lines of wooden embankments were laid bare at the distances of 53, 86, and 103 feet within the range of the existing wharf. At the same time, about 50 feet from the outer edge of the wharf, a wall was discovered running east and west, built with chalk rubble and faced with Purbeck stone, which was probably part of the old river-side wall. No trace of any important buildings was found in the whole of the area thus laid open, but between the embankments there were the remains of buildings interspersed with pits and layers of rushes in different stages of decomposition.

Sir William Tite (Catalogue of Antiquities) speaks of other discoveries along the river:—

“The excavations for sewers, constructed along this part of the boundary of London, appear satisfactorily to have ascertained that nearly the whole south side of the road forming the line from Lower Thames Street to Temple Street has been gained from the river by a series of strong embankments. At the making of the sewer at Wool Quay, the soil turned up was similar to that discovered at the Custom-House; and the mouth of an ancient channel of timber was found under the street. The ground also contained large quantities of bone skewers about 10 inches in length, perforated with holes in the thicker ends, recalling the bone skates employed by the youths of London about the end of the twelfth century, as described by FitzStephen. Between Billingsgate and Fish-street Hill the whole street was found to be filled with piling, and especially at the gateway leading to Botolph Wharf—which, it will be remembered, was the head of the oldest known London Bridge,—where the piles were placed as closely together as they could be driven, as well as106 for some distance on each side. In certain parts of the line the embankment was formed by substantial walling, as at the foot of Fish-street Hill, where a strong body of clear water gushed out from beneath it. At the end of Queen Street also, and stretching along the front of Vintners’ Hall, a considerable piece of thick walling was encountered; and another interesting specimen was taken up, extending from Broken Wharf to Lambeth Hill. At Old Fish-street Hill this embankment was found to be 18 feet in thickness; and it returned a considerable distance up Lambeth Hill, gradually becoming less substantial as it receded inland. Both of these walls were constructed of the remains of other works, comprising blocks of stone, rough, squared, and wrought and moulded, together with roofing-tiles, rubble, and a variety of different materials run together with grout.” (Pp. xxiv.-xxv.)

Again, on the construction of the new London Bridge it was found necessary to take down St. Michael’s, Crooked Lane, and to construct a large and deep sewer under the line of approach. Three distinct lines of embankment were discovered marking as many bulwarks by which ground was gained for the wharves. One of these lines, lying 20 feet under the south abutment of the Thames Street landmark, was made by the trunks of oak trees squared with the axe. Quantities of Roman things were found 100 feet north of the river.

During the demolition of houses for the construction of the new Coal Exchange opposite Billingsgate Market in 1847, the workmen came upon extensive remains of a Roman building. They lay about 60 feet behind the line of Thames Street, and about 14 feet below the level of the pavement. On its western side was a thick brick wall; the foundations were piles of black oak, showing that the building stood upon the Thames mud outside and below the Roman fort; next to the pavement, but without communication, was a chamber, which was believed by those who saw it to be a portion of the “laconicum” or sweating-room of a Roman bath, of which the hypocaust was also found. These interesting investigations could not be continued except by working under the warehouses beyond. They were therefore all covered over, and will probably never again be brought to light.

The sarcophagi which have been found are few in number (see App. IV.). The most important are—(1) that which was found at Clapton, (2) that found within the precincts of Westminster Abbey, and (3) that found in Haydon Square, Minories. The first was found in the natural gravel 2 feet 6 inches below the surface, lying due south-east and west; it is of white coarse-grained marble and is cut from a solid block. It is 6 feet 3 inches long, 1 foot 3 inches wide, and 1 foot 6 inches deep; the thickness is about 3½ inches. The inner surface is smooth, with a rise of half an inch as a rest for the head. No lid or covering was found. It is plain on all sides but the front, which is ornamented with a fluted pattern. In the centre is a medallion, about 12 inches in diameter, containing a bust of the person interred. There is a name, but it cannot be deciphered. The Westminster sarcophagus is107 preserved in the approach to the Chapter-House. That which was discovered at Clapton was of marble. Two, containing enriched leaden coffins, have been found at Bartholomew’s Hospital; and another on the banks of the Fleet River, near to Seacoal Lane. The position of some of these, distant from any cemetery, shows that the Roman custom of making tombs serve as landmarks or monuments of boundaries was followed in Roman London. In making the excavations for the railway station at Cannon Street, there was found across Thames Street a complete network of piles and transverse beams; this was traced for a considerable distance along the river bank and in an upward direction towards Cannon Street. These beams indicate, first, that the ground here—below the hillocks, beside the Walbrook—was marshy and yielding; and, next, that very considerable buildings were raised upon so solid and so costly a foundation.

The following are the most important of the Inscriptions and Sculptures:—

1. A tombstone found by Sir Christopher Wren in Ludgate Hill while digging the foundation of St. Martin’s Church. It is now among the Arundel Marbles at Oxford. The following is the inscription:—“D. M. VIVIO MARCIANO M LEG. II AUG. IANUARIA MARINA CONJUNX PIENTISSIMA POSUIT MEMORIAM.” Which is in full:—“Diis Manibus. Vivio Marciano militi legionis secundae Augustae. Januaria Marina conjunx pientissima posuit memoriam.”

2. Another was found in 1806 behind the London Coffee House, Ludgate Hill, with a woman’s head in stone and the trunk of a statue of Hercules. The following is the inscription:—D. M. CL. MARTINAE AN XIX ANENCLETUS PROVINC CONJUGI PIENTISSIMAE H. S. E.—“Diis Manibus. Claudiae Martinae annorum novendecim Anencletus Provincialis conjugi pientissimae hoc sepulchrum erexit.”

3. Found in Church Street, Whitechapel, about the year 1779:—D. M. JUL. VALIUS. MIL. LEG. XX. V. V. AN. XL. H. S. E. CA. FLAVIO. ATTIO. HER.—“Diis Manibus. Julius Valius miles legionis vicesimae Valerianae victricis annorum quadraginta hic situs est, Caio Flavio Attio herede.”

4. Found in the Tenter Ground, Goodman’s Fields, in 1787; 15 in. by 12 in., and 3 in. thick—of native green marble:—D. M. FL. AGRICOLA. MIL. LEG. VI. VICT.108 V. AN. XLII. DX ALBIA FAUSTINA CONJUGI INCOMPARABILI F. C.—“Diis Manibus. Flavius Agricola miles legionis sextae victricis vixit annos quadraginta duos dies decem Albia Faustina Conjugi incomparabili faciendum curavit.”

5. Found within the Tower, 1778; 2 ft. 8 in., by 2 ft. 4 in.:—DIS MANIB. T. LICINI ASCANIUS. F.—“Diis Manibus. Tito Licinio, Ascanius fecit.”

6. Found outside London wall near Finsbury Circus—now in the Guildhall Library:—D. M. GRATA DAGOBITI FIL AN XL SOLINUS CONJUGI KAR F C.—“Diis Manibus. Grata Dagobiti Filia annorum quadraginta Solinus conjugi karissimae fieri curavit.”

7. Found in Playhouse Yard, Blackfriars—formerly outside the City wall, now in the British Museum:—“Diis Manibus ... R. L. F. C. Celsus ... Speculator Legionis Secundae Augustae annorum ... natione Dardanus Gu ... Valerius Pudens et ... Probus Speculatores Leg. II. fieri curaverunt.”

8. Found on Tower Hill, 1852; 6 ft. 4 in., by 2 ft. 6 in.:—A ALFID. POMPO. JUSSA EX TESTAMENT ... HER. POS. ANNOR. LXX. NA AELINI H. S. EST.—“A Alfidio Pompo (Pomponio?) jussa ex testamento heres posuit, annorum septuaginta (Na Aelini?), hic situs est.”

9. Found also on Tower Hill; 5 ft. 4 in., by 2 ft. 6 in.:—“DIS ANIBUS ABALPINICLASSICIANI.”

10. Found at Pentonville, serving as a paving-stone before the door of a cottage:— “... URNI ... LEGXX GAC ... M ...”

11. Found in Nicholas Lane, near Cannon Street, June 1850, at the depth of 11 or 12 feet, lying close to a wall 2 feet in width. It is only a fragment:—“NUMC ... PROV ... BRITA ...”

12. Found on an ingot of silver within the Tower of London in 1777: “EX OFFI. HONORIM”—i.e. Ex officinâ—from the workshop of Honorinus.

As we have already said, the things that have been found are nearly all pagan. Only on two Roman pavements have been found the Christian symbols, on one coin, and on one stone in the Roman wall. This silence proves, to my mind, that the Christian religion, down to the middle of the fourth century, held a very obscure place among the many religions followed and professed by the people. Except in times of persecution, everybody worshipped any god he pleased—Christ, or Apollo, or the109 Sun, or the Mother. But those who followed the Christian faith were not the soldiers, or their captains, or the Imperial officers, or the rich merchants: they were the lower class, the craftsmen of the cities, and the slaves among whom the Christian hope prevailed.

During an excavation at Hart Street, Crutched Friars, there was found at a considerable depth below the surface a fragment of a group representing the Deæ Matres—the Three Mothers. The fragment measures 2 ft. 8 in. in length, 1 ft. 5 in. in width, and 1 ft. 8 in. in depth. The sculpture represented three female figures fully clothed with flowing draperies, each bearing in her lap a basket of fruit. Perhaps their sacellum or temple was close by, but no search for it seems to have been made. This is not the place for enlarging upon the worship of these strange goddesses. Their figures have been found at Winchester, at York, and along the Roman wall; but they were essentially German deities. That they have been found in this country side by side with the classical gods shows that here, as in all other Roman provinces, the people received a great mixture of gods from all parts of the world among their original gods. The Three Mothers represented the productive power of Nature: the fruits signify the annual harvest. It is easy to understand how, starting with this idea, the whole of life—birth, growth, strength, decay, and death—may be connected with the Mothers of all. We may worship the Sun as the creator, or the Deæ Matres as the producers. We may have Baal, Apollo, the Sun—the Father; or we may have Venus, Osiris, or the Matres—the Mothers. A port which was a place of resort for merchants of all nations would, in those days of universal respect and toleration of all gods, offer a strange collection of gods. Long before Christianity was established there were Christians in the City side by side with those who110 worshipped Nature as creator or producer—those who adopted the gods of the Romans and those who preserved the memory and the teaching of the Druids. But, whatever be said or conjectured, nothing can be more remarkable than the absence of Christian symbols.

Returning to the Roman remains found in London, we come to the wall paintings, of which a considerable number have been recovered—“cart-loads,” according to Roach Smith. “In some localities I have seen them carried away by cart-loads. Enough has been preserved of them to decide that the rooms of the house were usually painted in square panels or compartments, the prevailing colours of which were bright red, dark grey, and black, with borders of various colours.”

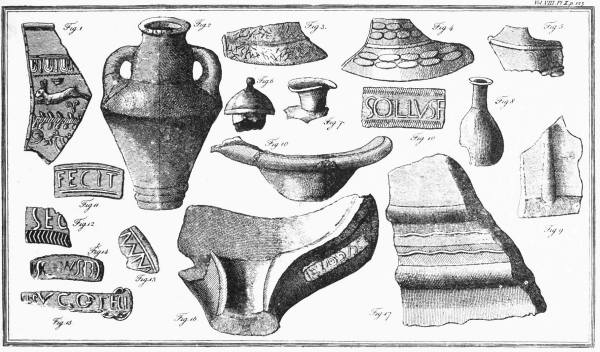

A quantity of pottery has also been found. Here, in fact, was an extensive industry in the making of fictile vessels. In the year 1677, on the north-west of St. Paul’s Cathedral, were discovered remains of Roman kilns: they were found and sketched by John Conyers. He says that there were four of them lying in the sandy loam from which they were constructed. The one he sketched was 5 feet deep, and the same in breadth. The kiln was full of the coarser kind of pottery. The figures show the form of the vessels. The potters’ marks are very numerous. Some show that the vessels were brought from abroad, but these are comparatively few; the remainder testify to the fact that London was largely engaged in this industry. The red glazed pottery, of which such quantity is found wherever there has been a Roman settlement, is clearly proved to have been made in Gaul and Germany and to have been imported. It was probably superior to the home-made ware. The designs with which the pottery is ornamented are executed with great skill and beauty. Mythological stories are represented, as that of Actæon and Diana, the labours of Hercules, and Bacchanalian processions. There are representations of flowers, fruits, and foliage, field sports, and the contests in the amphitheatre.

Of tiles, whether for roofing, for bonding, for the hypocaust, or other purposes, numbers have been dug up.

Were the windows in the houses of London glazed? Lactantius shows clearly that in his time there were glass windows. “Verius et manifestius est mentem esse quae per oculos ea, quae sunt opposita, transpiciat quasi per fenestras lucente vitro aut speculari lapide obductas.” And Seneca, much earlier, speaks of chambers covered with glass. In Pompeii both glass and the lapis specularis of Lactantius have been found in their window-frames. This should be quite conclusive. The enormous convenience of a window which would admit light and keep out the cold, especially in such a climate as ours, and the fact that in Italy such windows were in common use, are enough to show that these windows were used, because all the luxuries and conveniences of Rome were introduced here, if not by the natives, at least by the Roman officials. Pieces of glass, flat and semi-transparent, of a greenish hue, have111 been found in excavations, and are considered to be window glass. Indeed it would seem absolutely impossible to live in anything but a hut with a fire in the middle and an open door at the side without some such contrivance. There are many days in the year when it is impossible to work in the open air or in rooms exposed to the outer air. As soon as a house was constructed the glazed window—glazed with horn, or glass, or talc—must have followed.

Of coins a very large number have been dug up in excavations. These have been classified and described by Mr. C. Roach Smith in his book on Roman London.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content