Search london history from Roman times to modern day

79

Such, then, was the condition and the government of Roman London-Augusta. It is a City of great trade when first we find it mentioned. The trade had been diverted by a new road, now called Oxford Street, from the old line which previously passed across the more ancient settlement in the Isle of Thorney. London had been at first a British fort on a hillock overhanging the river; then a long quay by the river-side; then a collection of villa residences built in gardens behind the quay. The whole was protected by a Roman fort. By the fourth century, practically the trade of the entire country passed through the port of London. The wealth of the merchants would have become very great but for the fluctuations of trade, caused first by the invasions of Picts, Scots, Welsh, Irish, and “Saxons,” which interfered with the exports and imports; and next by the civil wars, usurpations, and tumults, which marked the later years of the Roman occupation. London under the Romans never became so rich as Ephesus, for instance, or Alexandria.

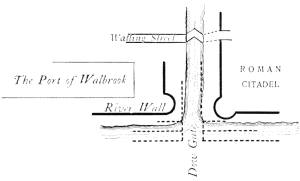

Let us next inquire what manner of city was this of London under the Romans. At the time of the Roman Conquest it was an unwalled village, protected partly by its situation, which was such as to leave it exposed to attack from one quarter only, before the construction of roads across the marsh; partly by its stockade fort between the Fleet and the Walbrook, and partly by the valour of its inhabitants—there are rumours of battles between the men of London and the men of Verulam. When Paulinus went out to meet Boadicea he left behind him a city without protection, either of walls or soldiers. Evidently there was then no Roman fort or citadel. That was built later. It was placed on that high ground already described, east of Walbrook; it had the advantage of a stream and a low80 cliff in the west, and a broad river and a low cliff on the south. This citadel was of extraordinary strength and solidity. Its foundations have been laid bare (1) at its south-west angle, under Cannon Street Railway Terminus; (2) at its east side, at Mincing Lane, twenty years ago; and (3) part of the north side was uncovered in 1892, on the south side of Cornhill. The wall of this fortress was, no doubt, much like the walls of Porchester and Pevensey which are still standing: it was quadrangular, and set with circular bastions. Its length was about 750 yards, its breadth about 500, so that the area enclosed must have been 375,000 square yards. There is no mention in history of this fortress; it was probably taken for granted by the historians that the castra stativa—the standing camp, the citadel—belonged to London in common with every other important town under Roman rule.

On the north side the wall of the fortress was protected by a ditch which ran from the eastern corner to the Walbrook. Traces of this ditch remained for a long time, and gave rise to the belief that there had been a stream running into the Walbrook; hence the name Langbourne. The main street of the fortress ran along the line of Cannon Street. London Stone, removed from its original position on the south side of the road, probably marked the site of the western gate.

As the town grew, houses, villas, streets arose all round the fortress and under its protection. Within the walls many remains have been found, but none of cemeteries. There were no interments within the walls, a fact which proves by itself the theory of the Roman fortress, if any further proof were needed. Outside the fort there is evidence of cemeteries that have been built over; pavements lie over forgotten graves. A bath has been found by the river-side: this was probably a public bath. When one reads of the general making London his head-quarters, it was in this walled place that his troops lay. In the enclosure were the offices of state, the mint, the treasury, the courts of justice, the arsenal, the record office, and the official residences. Here was the forum, though no remains have been discovered of this or any other public buildings. Here the civil administration was carried on; hither were brought the taxes, and here were written and received the dispatches and the reports.

This citadel was official London. If we wish to know what the City was like, we can understand by visiting Silchester, which was also a walled town. However, at Silchester as yet no citadel has been discovered. There are the foundations of a great hall larger than Westminster Hall. It had rooms and offices around it; it had a place of commerce where were the shops, the verandahs or cloisters in which the lawyers, the orators, the rhetoricians, and the poets walked and talked. Near at hand the guards of the Vicarius had their barracks.

Beneath and around the citadel of London the houses clustered in square insulæ; beyond, on the north side, stood the villas in their pretty gardens. The81 site of the great hall of the London citadel was perhaps discovered in 1666 after the Great Fire, when the workmen laid bare, east of what is now Cannon Street Railway Station, a splendid tessellated pavement.

Within the citadel was the forum, surrounded by lofty columns. One temple at least—probably more than one—lifted its columns into the air. One was to Fortune; another to Jupiter. In other parts of the town were temples to Cybele, to Apollo, to Baal or the sun god, to Mercury, to the Deæ Matres; to Bacchus, who stood for Osiris as well; and to Venus.

The character of the Roman remains dug up from time to time within these walls shows that it was formerly a place of great resort. Under the protection of this citadel, and later under the protection of the Pax Romana, villas were built up outside the walls for the residence of the better sort. All round the walls also sepulchral remains have been discovered; they were afterwards included in the larger wall of the city which was built towards the close of the fourth century.

London was then, and for many years afterwards, divided into London east and west of the Walbrook. On the western side was the quarter of the poorer sort; they had cottages on the foreshore—as yet there was no wall. The better class lived outside the fort, along the eastern side of Walbrook, and in Cornhill, Threadneedle Street, and Bishopsgate Street. Down below were the three Roman ports,82 afterwards called Billingsgate, Dowgate, and Queenhithe. Walking down Thames Street one finds here and there an old dock which looks as if it had been there from time immemorial.

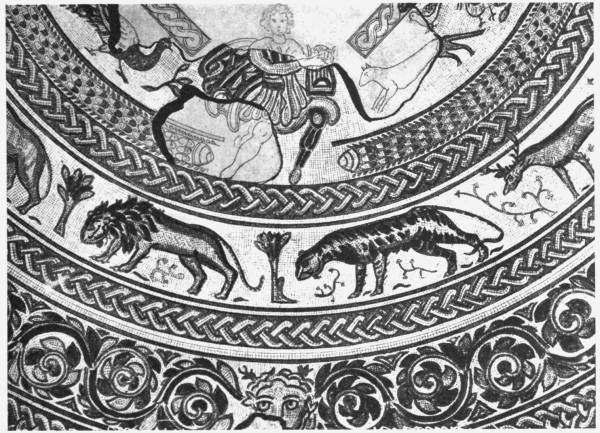

I have sometimes been tempted, when in Thames Street—that treasure-house of memories, survivals, and suggestions—to think that these narrow lanes sloping to the river are of Roman origin, left when all the rest was wrecked and lost, and that they are still of the same breadth as they were in the fourth century. This, however, is not the case. I shall show presently the origin and meaning of these narrow streets running up the hill from the river into Thames Street: they are all, in fact, connections of the quays on the foreshore with the merchants’ warehouses in Thames Street. Along the better streets, on the north of Thames Street, the traders put up their stalls and kept their shops; the stalls were at first mere temporary sheds resting against the walls of villas. These villas belonged, not to the millionaire Lucullus, for whose palace the whole world could be ransacked, but to the well-to-do merchant, whose taste was not much cultivated. He called in the best artist of the city. “Build me a villa,” he said, “as good as my neighbour’s. Let there be a fine mosaic pavement; let there be fountains; let there be paintings on the walls, lovely paintings—nymphs and fauns, nymphs bathing, plenty of nymphs, dancing girls, plenty of dancing girls; paint me Hercules drunk, Loves flying and playing tricks, warriors with shields, sea pieces, ships; paint me my own ships sailing. And take care of the hypocaust and the warming pipes, and see that the kitchen is suitably furnished.”

The earliest, the natural port of London was the mouth of the Walbrook, called afterwards Dowgate.

In the western wall of the Roman citadel was the gate which served at once for the road or street across the City to Newgate, and for that part of the trade which belonged to the citadel. The Walbrook at this time was a considerable stream. It was partly a tidal stream, but it was fed from above by many tributaries on the moorland. Here the ships first began to load and to unload. For their convenience quays were constructed on piles driven into the mud and shingle of the foreshore. As the trade increased, the piles were pushed out farther and the quays were broadened.

When trade increased and the difficulties of getting through the bridge were felt, another port was necessary. It was perfectly easy to construct one by cutting it out of the soft foreshore and then banking it up with strong piles of timber. Piles and beams were also driven in on either side for the support of quays, which could thus be extended indefinitely. The place chosen was what is now called Billingsgate. It was close to the bridge and the bridge gate; so that while goods could be landed here for the trade of the City—whence they could be easily distributed throughout the north and midland of the83 island,—communication was established with the south by means of the bridge (see Appendices I. and II.).

Later on, but one knows not when, the port of Queen Hythe, formerly Edred’s Hythe, was similarly constructed. I am inclined to believe also that Puddle Dock represents another ancient port; but whether Roman or Saxon, it is now impossible to decide.

The poorer part of the City was that part lying between Puddle Dock and Dowgate: we do not find tessellated pavements here, nor remains of great buildings. The houses which stood upon the pavements were modest compared with the villas of the Roman millionaire; but they were splendid compared with other houses of the City.

For the convenience of the better sort there was the bath, in which everybody spent a part of the day; for the merchants there were the quays; there was the theatre; and there was the amphitheatre. It is true that no trace has ever been found of theatre or of amphitheatre; but it is also true that until recently no trace was found of the Roman citadel, and, as I have said, no trace has ever been found of forum or of temples. We will return to this subject later.

To one standing at the south end of the narrow wooden bridge across the Thames, Augusta, even before the building of the wall, appears a busy and important place. Exactly opposite the bridge, on a low eminence, was a wall, strong though low, and provided with rounded bastions. Above the wall were seen the columns of the forum and of two temples, the roofs of the great hall of justice and of the official offices and residences.

Along the quays were moored the ships. On the quay stood sheds for warehouses in a line. Behind these warehouses were barracoons for the reception of the slaves waiting to be transported to some other part of the Empire, there to await what Fortune had in store for them—perhaps death in a gladiatorial fight, perhaps service on a farm, perhaps the greatest gifts of Fortune, viz. a place in a Roman cohort, opportunities for showing valour and ability, an officer’s commission, the command of a company, then of a legion, then of a victorious army; finally, perhaps the Purple itself and absolute rule over all the civilised world. The streets behind the warehouses were narrow and steep, the houses in them were mean. Everywhere within the area afterwards enclosed by the wall were villas, some small, some large and stately. It was a noisy city, always a noisy city—nothing can be done with ships without making a noise. The sailors and the stevedores and the porters sang in chorus as they worked; the carts rolled slowly and noisily along the few streets broad enough to let them pass; mules in single file carried bales in and out of the city; slaves marched in bound and fettered; in the smaller houses or in workshops every kind of trade was carried on noisily. Smoke, but not coal smoke, hung over all like a canopy.

84

In such a restoration of a Roman provincial town one seems to restore so much, yet to leave so much more. Religion, education, literature, the standard of necessities and of luxury, the daily food, the ideas of the better classes, the extent, methods, and nature of their trade, the language, the foreign element—none of these things can be really restored.

Under the protection of the citadel the merchants conducted their business; under its protection the ships lay moored in the river; the bales lay on the quays; and the houses of the people, planted at first along the banks of the Walbrook, stretched out northwards towards the moor, and westwards as far as the river Fleet.

It is strange that nothing should be said anywhere about so strong and important a place as the citadel. When was it built, and by whom? When was it destroyed, and by whom? Were the walls standing when the Saxons began their occupation? It appears not, because, had there been anything left, any remains or buildings standing, any tradition of a fortress even, it would have been carried on. The citadel disappeared and was forgotten until its foundations were found in our time. How did this happen? Its disappearance can be explained, according to my theory, by the history of the wall (see p. 112): all the stones above ground, whether of citadel, temple, church, or cemetery, were seized upon to build the wall.

Across the river stood the suburb we now call Southwark, a double line of villas beside a causeway. It has been suggested that Southwark was older than London, and that it was once walled in. The only reasons for this theory are: that Ptolemy places London in Kent—in which he was clearly wrong; that the name of Walworth might indicate a city wall; that remains of villas have been found in Southwark; and that a Roman cemetery has been found in the Old Kent Road. But the remains of houses have only been found beside the high road leading from the bridge. They were built on piles driven into the marsh. Up till quite recent times the whole south of London remained a marsh with buildings here and there; they were erected on a bank or river wall, on the Isle of Bermond, on the Isle of Peter, beside the high road. And there has never been found any trace of a wall round Southwark, which was in Roman times, and has always been, the inferior suburb—outside the place of business and the centre of society. Every town on a river has an inferior suburb on the other side—London, Paris, Liverpool, Tours, Florence: all busy towns have inferior transpontine suburbs. Southwark was always a marsh. When the river-bank was constructed the marsh became a spongy field covered with ponds and ditches; when the causeway and bridge were built, people came over and put up villas for residence. In the Middle Ages there were many great houses here, and the place was by some esteemed for its quiet compared with the noise of London, but Southwark was never London.

85

Besides the bridge, there was a ferry—perhaps two ferries. The name of St. Mary Overies preserves the tradition. There are two very ancient docks, one beside the site of the House of St. Mary Overies, and one opposite, near Walbrook. In these two docks I am pleased to imagine that we see the ancient docks of London ferry to which belongs the legend of the foundation of the House.

Let us return to the question of amphitheatre and theatre. There must have been both. It is quite certain that wherever a Roman town grew up an amphitheatre grew up with it. The amphitheatre was as necessary to a Roman town as the daily paper is to an American town.

It has been suggested that there was no amphitheatre, because the city was Christian. There may have been Christians in the city from the second century; everything points to the fact that there were. It is impossible, however, to find the slightest trace of Christian influence on the history of the city down to the fourth century. W. J. Loftie thinks that the dedication of the churches in the lower and poorer parts of the town—viz. to SS. Peter, Michael, James, and All Saints—shows that there were Christian churches on those sites at a very early period. This may be true, but it is pure conjecture. It is absurd to suppose that a city, certainly of much greater importance than Nîmes or Arles—where were both theatre and amphitheatre,—and of far greater importance than Richborough—where there was one,—should have no trace of either. Since Bordeaux, Marseilles, Alexandria, and other cities of the Roman Empire were not Christian in the second and third centuries, why should London be? Or if there were Christians here in quite early times, theirs was not the dominant religion, as is clearly shown by the Roman remains. There must have been an amphitheatre—where was it? To begin with, it was outside the City. Gladiators and slaves reserved for mock battles which were to them as real as death could make them, wild beasts, the company of ribalds who gathered about and around the amphitheatre, would not be permitted within the City. Where, then, was the amphitheatre of London?

At first one turns to the north, with its gardens and villas and sparse population. The existence of the villas will not allow us to place the amphitheatre anywhere in the north near the Walbrook.

When the modern traveller in London stands in the churchyard of St. Giles’s, Cripplegate, he looks upon a bastion of the Roman wall where the wall itself took a sudden bend to the south. It ran south till it came to a point in a line with the south side of St. Botolph’s Churchyard (the “Postmen’s Park”), where it again turned west as far as Newgate.

It thus formed nearly a right angle—Why? There is nothing in the lie of the ground to account for this deviation. No such angle is found in the eastern part of the wall. There must have been some good reason for this regular feature in the wall. Was the ground marshy? Not more so than the moorland through which the86 rest of the wall was driven. Can any reason be assigned or conjectured? I venture to suggest, as a thing which seems to account for the change in the direction of the wall, that this angle contained the amphitheatre, the theatre, and all the buildings and places, such as the barracks, the prisons, the dens and cages, and the storehouse, required for the gladiatorial shows. I think that those who built the wall, as I shall presently show, were Christians; that they were also, as we know from Gildas, superstitious; that they regarded the amphitheatre, and all that belonged to it, as accursed; and that they would not allow the ill-omened place of blood and slaughter and execution to be admitted within the walls. It may be that a tradition of infamy clung to the place after the Roman occupation: this tradition justifies and explains the allocation to the Jews of the site as their cemetery. The disappearance of the amphitheatre can be fully explained by the seizure of the stones in order to build the wall.

Mr. C. Roach Smith, however, has proposed another site for the theatre, for which he tenders reasons which appear to me not, certainly, to prove his theory, but to make it very possible and even probable. Many Roman theatres in France and elsewhere are built into a hill, as the rising ground afforded a foundation for the seats. That of Treves, for instance, will occur to every one who has visited that place. Mr. Roach Smith observed a precipitous descent from Green Arbour Court into Seacoal Lane—a descent difficult to account for, save by the theory that it was constructed artificially. This indeed must have been the case, because there was nothing in the shape of a cliff along the banks of the Fleet River. Then why was the bank cut away? Observe that the site of the Fleet Prison was not on a slope at all, but on a large level space. We have therefore to account for a large level space backed by an artificial cliff. Is it not extremely probable that this points out the site of the Roman theatre, the seats of which were placed upon the artificial slope which still remains in Green Arbour Court?

Mr. Roach Smith read a paper (Jan. 1886) placing this discovery—it is nothing less—on record before the London and Middlesex Archæological Association. The remarkable thing is that no one seems to have taken the least notice of it.

Assuming that he has proved his case, I do not believe that he is right as to the houses being built upon the foundations of the theatre, for the simple reason that, as I read the history of the wall in the stones, every available stone in London and around it was wanted for the building of the wall. It was built in haste: it was built with stones from the cemeteries, from the temples, from the churches, from the old fortress, and from the theatre and the amphitheatre outside the wall. As regards the latter, my own view remains unaltered; I still think that the angle in the wall was caused by the desire to keep outside the amphitheatre with all its memories of rascality and brutality.

Treves (Colonia Augusta Treverorum) and Roman London have many points in87 common, as may be apprehended most readily from the accompanying comparison in which Roman Treves and Roman London are placed side by side. We may compare the first citadel of London on the right bank of the Walbrook with Treves; or we may compare the later London of the latter part of the fourth century, the wall of which was built about A.D. 360-390, with Treves.

1. The citadel of London had its western side protected by a valley and a stream whose mouth formed a natural port. The valley was about 140 feet across; the stream was tidal up to the rising ground, with banks of mud as far, at least, as the north wall of the citadel. On the south was a broad river spanned by a bridge. There were three gates: that of the north, that of the west, and that of the bridge on the south. Within the citadel were the official buildings, barracks, residences, and offices. Two main streets crossed at right angles. About half a mile to the north-west (according to my theory) was the amphitheatre. On the north and east was an open moor. On the south a marsh, with rising ground beyond. By the river-side, near the bridge, were the baths.

2. Colonia Augusta Treverorum.—These details are almost exactly reproduced in Treves. We have a broad river in front. On one side a stream which perhaps branched off into two. The gate which remains (the Porta Nigra) shows the direction of the wall on the north from the river. A long boulevard, called at present the Ost Allee, marks the line of the eastern wall, which, like that of London, occupied the site of the Roman wall. A bend at right angles at the end of this boulevard includes the Palace and other buildings. It therefore represents the site of the ancient wall or that of a mediæval wall. It is quite possible that the mediæval wall of the city included a smaller area than the Roman wall, and that the two round towers, here standing in position with part of the wall, represent the mediæval wall. It is also possible, and even probable, that they stand on the site of the Roman wall, which just below the second, or at the second, bent round again to the south as far as the stream called the Altbach, and so to the west as far as the river. That this, and not the continuation of the line of towers, was the course of the Roman wall, is shown by the fact that the baths, the remains of which stand beside the bridge, must have been within, and not outside, the wall. The river wall, just like that of London, ran along the bank to the bridge, and was stopped by the outfall of a small stream. The ground behind the river wall gradually rose. On the other side was a low-lying marsh, beyond which were lofty hills—not gradually rising hills as on the Surrey side of the Thames. The city was crossed by two main arteries, which may still be traced. An extensive system of baths was placed near the bridge on the east side. Within the wall were the Palace of the Governor or of the Emperor, and a great building now called the Basilica; and between them, the remains now entirely cleared away for the exercise ground, once the garden of the barracks. There were three gates, perhaps four. One of them, a most noble monument, still survives. A Roman cemetery has been found88 beyond the Altbach in the south, and another in the north, outside the Porta Nigra.

3. The comparison of Roman Treves with the later Roman London is most curious, and brings out very unexpectedly the fact that in many respects the latter was an enlargement of the citadel. We know that the wall was constructed hastily, and that all the stonework in the City was used in making it. Like the citadel, however, and like Treves, it had a stream on one side, baths and a bridge and a port within the walls; while the official buildings, as at Treves, were all collected together in one spot. We also find the curious angle, which at Treves may be accounted for by an enlargement of the wall, and at London by the custom of keeping the amphitheatre outside the City as a place foul with associations of battle, murder, massacre, and the ribald company of gladiators, retiarii, prisoners waiting the time of combat and of death, wild beasts and their keepers, and the rabble rout which belonged to this savage and reckless company.

That part of London lying to the west of Walbrook was crowded with the houses of the lower classes, and with the warehouses and stores of the merchants. These extended, as they do to this day, all the way from the Tower to Blackfriars. On the rising ground above were the villas of the better class, some of them luxurious, ample, decorated with the highest art, and provided with large gardens. These villas extended northwards along the banks of the little Walbrook. They are also found on the south side in Southwark, and on the west side on Holborn Hill. The principal street of Augusta was that afterwards called Watling Street, which, diverted from the old Watling Street where Marble Arch now stands, carried all the trade of the country through London by way of Newgate, over the present site of St. Paul’s, and so through the citadel, to the market-place and to the port. Another street led out by way of Bishopsgate to the north; and a third, the Vicinal Way, to the eastern counties. The bridge led to a road running south to Dover. There was also a long street, with probably many side streets out of it, as there are at this day, along the Thames.

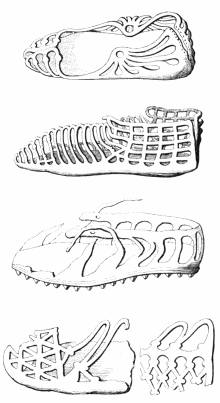

The things which remain of Roman London and may be seen in our museums are meagre, but they yield a good deal of information as to the condition and the civilisation of the City. The foundation of large villas, the rich mosaics and pavements, the remains of statues, the capitals of pillars, the coins, and the foundations of massive walls, clearly indicate the existence of much wealth and considerable comfort. The smaller things in the glass cases, the keys, the hairpins, the glass bottles, the statuettes, the bells, the tools, the steelyards, the mirrors, all point to a civilisation closely imitating that of the capital itself.

It is not to a native of London that we must turn for the life of the better class89 in a provincial city of the fourth century, but to a native of Gaul. Ausonius is a writer whose works reveal the daily life of a great city in Gaul. He was born of good family on both sides. His father was a physician; his grandfather a so-called “Mathematician,” in reality one who still practised the forbidden mystery of astrology. Ausonius himself was educated at Toulouse, and he opened a school of rhetoric at Bordeaux. The rhetoricians not only taught, but also practised, the art of oratory. Whether all rhetoricians were also poets is uncertain: the mere making of verse is no more difficult to acquire than the composition of oratory. There were two classes of teachers: the grammarian, of whom there were subdivisions—the Latin grammarian, skilled in Latin antiquities, and the Greek grammarian, who had studied Greek antiquities; and, above the grammarian, the rhetorician. In every important town over the whole Empire were found the rhetorician and the grammarian; they exchanged letters, verses, compliments, and presents. In a time of universal decay, when no one had anything new to say, when there was nothing to stimulate or inspire nobler things, the language of compliment, the language of exaggeration, and the language of conceit filled all compositions. At such a time the orator is held in greater respect even than the soldier. In the latter the townsman saw the preserver of order, the guardian of the frontier, the slayer of the barbarians who were always pressing into the Empire. He himself carried no arms: he represented learning, law, literature, and medicine. Ausonius himself, in being elevated to the rank of consul, betrays this feeling. He compares himself with the consuls of old: he is superior, it is evident, to them all, save in one respect, the warlike qualities. These virtues existed no longer: the citizen was a man of peace; the soldier was a policeman. If this was true of Bordeaux, then far from the seat of any war, it was much more true in London, which every day saw the arrival and the dispatch of slaves captured in some new border fray, while the people themselves never heard the clash of weapons or faced the invader with a sword.

Another profession held greatly in honour was that of the lawyer. The young90 lawyer had a five years’ course of study. There were schools of law in various parts of the Empire which attracted students from all quarters, just as in later times the universities attracted young men from every country. From these lawyers were chosen the magistrates.

Medicine was also held greatly in honour; it was carefully taught, especially in southern Gaul.

The learned class was a separate caste: with merchants and soldiers, the lawyers, orators, grammarians, and physicians had nothing to do. They kept up among themselves a great deal of the old pagan forms. If they could no longer worship Venus, they could write verses in the old pagan style about her. Probably a great many continued, if only from habit, the pagan customs and the pagan manner of thought. The Church had not yet given to the world a crowd of saints to take the place of the gods, goddesses, nymphs, satyrs, and sprites which watched over everything, from the Roman Empire itself down to a plain citizen’s garden.

The theatre was entirely given over to mimes and pantomimes: comedy and91 tragedy were dead. The pieces performed in dumb show were scenes from classical mythology. They were presented with a great deal of dancing. Everybody danced. Daphne danced while she fled; and Niobe, dancing, dissolved into tears. The circus had its races; the amphitheatre its mimic contests and its gladiatorial displays.

These things were done at Bordeaux; it is therefore pretty certain that they were also done in London, whose civilisation was equally Gallo-Roman. London was a place of importance equal with Bordeaux; a place with a greater trade; the seat of a Vicarius Spectabilis, a Right Honourable Lieutenant-Governor; one of the thirteen capitals of the thirteen Dioceses of the Roman Empire.

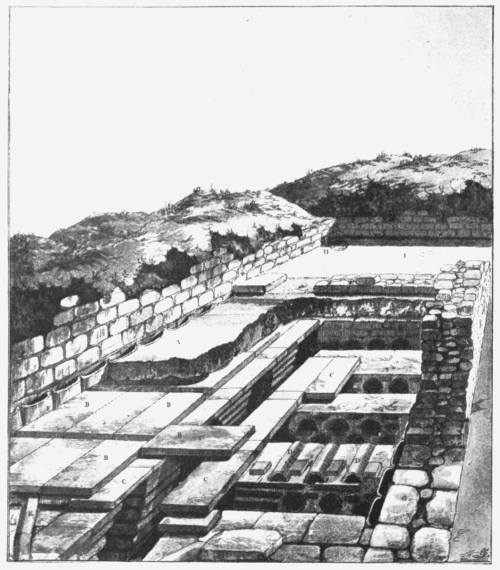

Any account of Roman London must include a description and plan of a Roman villa. The one I have chosen is the palatial villa which was recovered by Samuel Lysons exactly a hundred years ago at Woodchester. The plan is given in his book, An Account of Roman Antiquities discovered at Woodchester; it shows the arrangement of the rooms and the courts.

“The visitor approaching this villa when it was standing observed before him a long low wall with an entrance arch. The wall was probably intended as some kind of fortification; the people in the house numbered enough to defend it against any wandering company of marauders. Within the entrance, where he was received by a porter or guard, the visitor found himself in a large square court, the sides of which were 150 feet. On either side, to east and west, were build92ings entered from the great court: in one there were twelve rooms; in the other a curious arrangement of rooms communicating with each other which were thought to be the baths. The rooms on the west side were perhaps the chambers and workshops of the slaves and servants.

On the north side a smaller gateway gave access to a court not so large as the first, but still a good-sized court, 90 feet square; it was surrounded on three sides by a gallery, which was closed in winter, as the hypocaust under it indicates. From this court access was obtained to a lovely hall, decorated with a mosaic pavement of great artistic value, with sculptures, paintings, vases, and glass. On either side of this hall were chambers, also decorated in the same way. Under the floors of the chambers was the hypocaust, where were kindled the fires whose hot air passed through pipes warming all the chambers. Fragments of statues, of which one was of Magnentius the usurper, also glass, pottery, marble, horns, coins. The building covered an area of 550 feet by 300 feet, and it is by no means certain that the whole of it has been uncovered.

It is interesting to note that on one of the mosaics found at this place is the injunction ‘... B][N][C ...’18—that is, Bonum Eventum Bene Colite—Do not forget to worship Good Luck. To this god, who should surely be worshipped by all the world, there was a temple in Rome.

The Roman Briton, if he lived in such state as this, was fortunate above his fellows. But in the smaller villas the same plan of an open court, square, and built upon one, two, or more sides, prevailed. The walls were made of stone up to a certain height, when wood took the place of stone; the uprights were placed near together, and the interstices made air-tight and water-tight with clay and straw; the roof was of shingles or stone tiles. Wall paintings have been found everywhere, as we have already seen; the pavements were in many cases most elaborate mosaics.”

The construction of a villa for a wealthy Roman Briton is easy to be understood. As to the question of the smaller houses, it is not so easy to answer. A small house, detached, has been found at Lympne. It was about 50 feet long and 30 feet broad. The plan shows that it was divided into four chambers, one of which had a circular apse. The rooms were all about the same size, namely, above 22 feet by 14 feet. A row of still smaller houses has been found at Aldborough. Almost all the streets in London stand upon masses of buried Roman houses. If we wish to reconstruct the city, we must consider not only the villas in the more open spaces as the official residences in the citadel, but also the streets and alleys of the poorer sort. Now at Pompeii the streets are narrow; they are arranged irregularly; there are only one or two in which any93 kind of carriage could pass. The same thing has been observed at Cilirnum (Chesters), in Northumberland, and at Maryport in Cumberland. Very likely the narrow streets leading north of Thames Street are on the same sites as the ancient Roman streets of London in its poorer and more crowded parts. It stands to reason that the houses of the working people and the slaves could not be built of stone.

The nature of the trade of London is arrived at by considering—(1) What people wanted; (2) what they made, produced, and grew for their own use; and (3) what they exported.

To take the third point first. Britain was a country already rich. The south part of the island, which is all that has to be considered, produced iron, tin, lead, and copper; coal was dug up and used for fuel when it was near the surface; skins were exported; and the continual fighting on the march produced a never-failing supply of slaves for the gladiatorial contests. Wheat and grain of all kinds were also largely grown and exported.

As for manufactures, pottery was made in great quantities, but not of the finer kinds. Glass was made. The art of weaving was understood. The arts of painting, mosaic work, and building had arrived at some excellence. There were workmen in gold and other metals.

As for what people wanted. Those who were poor among them wanted nothing but what the country gave them; for instance, the river was teeming with fish of all kinds, and the vast marshes stretching out to the mouth of the Thames were the homes of innumerable birds. No one need starve who could fish in the river or trap birds in the marsh. In this respect they were like the94 common sort, who lived entirely on the produce of their own lands and their own handiwork till tea, tobacco, and sugar became articles of daily use. The better class, however, demanded more than this. They wanted wine, to begin with; this was their chief want. They wanted, besides, silks for hangings and for dress, fine stuffs, statues, lamps, mirrors, furniture, costly arms, books, parchment, musical instruments, spices, oil, perfumes, gems, fine pottery.

The merchants of London received all these things, sent back the ships laden with the produce of the country, and dispatched these imported goods along the high roads to the cities of the interior and to the lords of the villas.

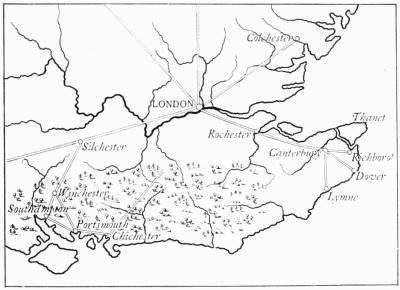

London was the centre of at least five great high roads. In this respect it was alone among the towns of Roman Britannia. These highways are laid down in Guest’sOrigines Celticæ. They connect the City with every part of the island: on the north-east with Colchester; on the north with Lincoln and York; on the north-west with Uriconium (Wroxeter), for Shrewsbury and Wales and Ireland; on the west with Silchester, for Winchester and Salisbury; on the south-east with Richborough, Dover, and Lympne or Lymne; and on the south with Regnum (Chichester)—if we may fill in the part between London and Dorking which Guest has not indicated.

This fact is by itself a conclusive proof that London was the great commercial centre of the island, even if no other proofs existed. And since the whole of the trade was in the hands of the London merchants, we can understand that in times when there was a reasonable amount of security on the road and on the Channel, when the Count of the Saxon Shore patrolled the high seas with his fleet, and the Duke of Britain kept back the Scot and the Pict, the city of Augusta became very wealthy indeed. There were, we have seen, times when there was no safety, times when the pirate did what he pleased and the marauder from the north roamed unmolested about the country. Then the London merchants suffered and trade declined. Thus, when Queen Boadicea’s men massacred the people of London, when the soldiers revolted in the reign of Commodus, when the pirates began their incursions before the establishment of the British fleet, when Carausius used the fleet for his own purposes, and in the troubles which preceded and followed the departure of the legion, there were anxious times for those engaged in trade. But, on the whole, the prosperity of London was continuous for three hundred and fifty years.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content