Search london history from Roman times to modern day

57

The second appearance of London in history springs out of the revolt of the Iceni under Boudicca, or, as her name is Latinised, Boadicea. She was the widow of Prasutagus, King of the Iceni, who bequeathed his kingdom, hoping thereby to make the possession safe, to the Roman Cæsar jointly with his wife and daughters. The precaution proved useless. His kingdom was pillaged by the captains, and his wife and daughters were dishonoured. With the swiftness of a summer storm, the Britons from Norfolk, from the fens, from the north, rose with one consent and poured down upon the Roman colony. The town of Camulodunum was unfortified; there were no troops except the veterans. Suetonius Paulinus was far away in North Wales when the great revolt broke out. The veterans fought for their lives: those were happy who fell in battle: the prisoners were tortured to death; the women and children were slaughtered like the rest; the 9th Legion, marching to relieve the colony, was cut to pieces, only the cavalry escaping.

Paulinus hastened to London—observe that on its first appearance in history London is a large town. But he judged it best not to make this place his seat of war, and marched out, in spite of the prayers of the inhabitants. He allowed, however, those who wished to follow with the army. As soon as the Roman army was out of the town, the Britons—there was clearly more than one army of rebels—entered it and slaughtered every man, woman, and child. At the same time they entered Verulam and murdered all the population. Over 70,000 people are said to have been massacred in the three towns of London, Camulodunum, and Verulam. We need not stop to examine into the figures. It is enough that the three towns were destroyed with, we are told, all their inhabitants. The battle at which Suetonius Paulinus defeated the rebels was decisive. The captive Queen killed herself; the tribes dispersed. Then followed a time of punishment; and, as regards London, some must have escaped, for those who still lived went back to the City, rebuilt their houses, and resumed their ordinary occupations.

The Roman conquest, however, was by no means complete. That remained to be accomplished by Agricola. There was continual trouble north of Hadrian’s Wall, but the rest of the island remained in peace for more than a hundred years after the58 defeat of Boadicea. As for London, the City increased every year in wealth and population. The southern part of the island became rapidly Romanised; tranquillity and order were followed by trade and wealth; the country was quickly covered with populous and prosperous towns; the Roman roads were completed; the Roman authority was everywhere accepted.

The distribution of the Roman legions after the defeat of the British Queen is significant. Five only remained: the 2nd, stationed at Isca Silurum—Caerleon; the 6th and 9th, at York; the 14th, at Colchester for a time until it was sent over to Germany; and the 20th, at Deva—Chester. There was no legion in the east—the country of Queen Boadicea; therefore there was no longer anything to fear from that quarter. There was none in London; there was none in the south country. In addition to the legions there were troops of auxiliaries stationed along the two walls of Antoninus and Hadrian, and probably along the Welsh frontier.

59

We may pass very briefly in review the leading incidents of the Roman occupation, all of which are more or less directly connected with London.

There can be little doubt that after the massacre by the troops of Boadicea the Romans built their great fortress on the east side of the Walbrook. Some of the foundations of the wall, of a most massive kind, have been found in five places. The fortress, which extended from the Walbrook to Mincing Lane, and from the river to Cornhill, occupied an area of 2250 by 1500 feet, which is very nearly the space then considered necessary in laying out a camp for the accommodation of a complete legion. It seems as if the Romans had a certain scale of construction, and laid out their camps according to the scale adopted.

Within this fortress were placed all the official courts and residences: here was the garrison; here were the courts of law; this was the city proper. I shall return to the aspect of the fort in another chapter.

We may safely conclude that the massacre of London by the troops of Boadicea would not have occurred had there been a bridge by which the people could escape. It is also safe to conclude that the construction of a bridge was resolved upon and carried out at the same time as that of the fortress. In another place will be found my theory as to the kind of bridge first constructed by the Roman engineers. In this place we need only call attention to the fact of the construction and to the gate which connected the fort with the bridge.

After the campaigns of Agricola, history speaks but little of Britain for more than half a century; though we hear of the spread of learning and eloquence in the north and west:—

And Martial says, with pride, that even the Britons read his verses:—

These, however, may be taken as poetic exaggerations.

The Romans, it is quite certain, were consolidating their power by building towns, making roads, spreading their circle of influence, and disarming the people. It has been remarked that the tessellated pavements found in such numbers frequently represent the legend of Orpheus taming the creatures—Orpheus was Rome; the creatures were her subjects.

The first half-century of occupation was by no means an unchequered period of success: the savage tribes of the north, the Caledonii, were constantly making raids and incursions into the country, rendered so much the easier by the new and excellent high roads.

60

In the year 120, Hadrian visited Britain, and marched in person to the north. As a contemporary poet said—

He built the great wall from the Solway to the Tyne: a wall 70 miles long, with an earthen vallum and a deep ditch on its southern side, and fortified by twenty-three stations, by castles, and wall towers.

Twenty years later, the Proprætor, Lollius Urbicus, drove the Caledonians northwards into the mountains, and connected the line of forts erected by Agricola from the Forth to the Clyde by a massive rampart of earth called the wall of Antoninus.

Again, after twenty years, the Caledonians gave fresh trouble, and were put down by Ulpius Marcellus under Commodus. On his recall there was a formidable mutiny of the troops. Pertinax, afterwards, for three short months, Emperor, was sent to quell the mutiny. He failed, and was recalled. Albinus, sent in his place, was one of the three generals who revolted against the merchant Didius Julianus, when that misguided person bought the throne.

At this time the Roman province of Britain had become extremely rich and populous. Multitudes of auxiliary troops had been transplanted into the island, and had settled down and married native women. The conscription dealt with equal rigour both with their children and the native Britons. Albinus, at the head of a great army, said to have consisted of 150,000 men, crossed over to Gaul and fought Severus, who had already defeated the third competitor, Niger, at Lyons, when he too met with defeat and death.

Severus, the conqueror, came over to Britain in 208-209. His campaign in the north was terminated by his death in 212.

For fifty years the island appears to have enjoyed peace and prosperity. Then came new troubles. I quote Wright15 on this obscure period:—

61

“Amid the disorder and anarchy of the reign of Gallienus (260 to 268), a number of usurpers arose in different parts of the Empire, who were popularly called the thirty tyrants, of whom Lollianus, Victorinus, Postumus, the two Tetrici, and Marius are believed on good grounds to have assumed the sovereignty in Britain. Perhaps some of these rose up as rivals at the same time; and from the monuments bearing the name of Tetricus, found at Bittern, near Southampton, we are perhaps justified in supposing that the head-quarters of that commander lay at the station of Clausentum and along the neighbouring coasts. We have no information of the state of Britain at this time, but it must have been profoundly agitated by these conflicting claimants to empire. Yet, though so ready to rise in support of their own leaders, the troops in Britain seem to have turned a deaf ear to all solicitations from without. When an officer in the Roman army, named Bonosus, born in Spain, but descended of a family in Britain, proclaimed himself Emperor, in the reign of Aurelian, and appealed for support to the western provinces, he found no sympathy among the British troops. Another usurper, whose name has not been recorded, had taken advantage of his appointment to the government of the island by the Emperor Probus to assume the purple. The frequency of such usurpations within the island seem to show a desire among the inhabitants to erect themselves into an independent sovereignty. We are told that a favourite courtier of Probus, named Victorinus Maurusius, had recommended this usurper to the proprætorship, and that, when reproached on this account by the Emperor, Victorinus demanded permission to visit Britain. When he arrived there, he hastened to the Proprætor, and sought his protection as a victim who had narrowly escaped from the tyranny of the Emperor. The new sovereign of Britain received him with the greatest kindness, and in return was murdered in the night by his guest. Victorinus returned to Rome to give the Emperor this convincing proof of his ‘loyalty.’ Probus was succeeded in the Empire by Carus, and he was followed by Diocletian, who began his reign in the year 284, and who soon associated with himself in the Empire the joint Emperor Maximian. Their reign, as far as regards Britain, was rendered remarkable chiefly by the successful usurpation of Carausius.”

By far the most remarkable of the British usurpers whose history is connected with that of London was Carausius.

This successful adventurer belonged to a time when there sprang up every day gallant soldiers, men who had risen from the ranks, conspicuous by their valour, fortunate in their victories, beloved and trusted by their soldiers. The temptation to such an one to assume the purple was irresistible. Examples of such usurpation were to be found in every part of the unwieldy Empire. To be sure they ended, for the most part, in defeat and death. But, then, these men had been facing death ever since they could bear arms. On any day death might surprise them62 on the field. Surely it was more glorious to die as Imperator than as the mere captain of a cohort. Such usurpers, again, held the crown as they won it, by the sword. They were like the King of the Grove, who reigned until a stronger than he arose to kill him. Carausius was a King of the Grove.

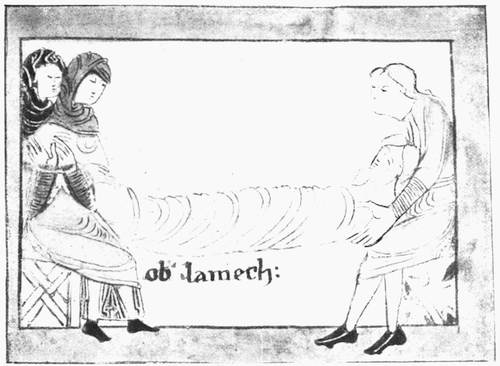

His history, so far as it has been told at all, is written by his enemies. But he was an important man. During his time of power he caused an immense number of coins to be struck, of which there remain some three hundred types. These were arranged about the year 1750 by that eminent antiquary Dr. Stukeley, who not only figured, described, and annotated them, but also endeavoured to restore from the coins the whole history of the successful usurper. Dr. Stukeley—a thing which is rare in his craft—possessed the imagination of a novelist as well as the antiquary’s passion for the chase of a fact.

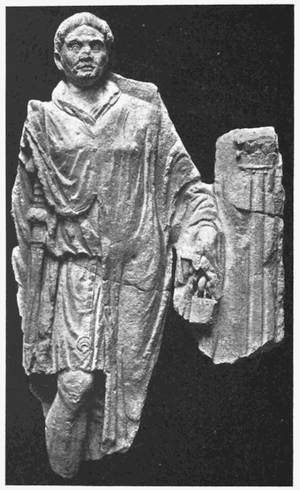

Carausius was a Briton, born in Wales, at the city now called St. David’s. He was of royal descent. He was of noble presence and great abilities. Maximian found it necessary to continue him in his commands, and bestowed upon him the distinction of a command in the Empress’s Regiment, the Ala Serena—Diocletian’s wife was named Eleutheria Alexandra Serena,—and committed to him the conduct of the expedition against the revolted Gauls. Carausius executed his trust faithfully and effectually. In reward for this service Maximian appointed him to the important dignity of Comes littoris Saxonici, with command of the fleet, whose duty it was to beat back the pirates always cruising about the narrow seas in search of booty. The head-quarters of the fleet were at Gesoriacum (Boulogne), a central position for operations in the Channel or the North Sea.

In the following year Carausius again fought loyally on the side of Maximian. But, says Stukeley, “in person, character, and behaviour he so outshone the Emperor that he exercised an inveterate envy against him.” Shortly afterwards Carausius, being informed that the Emperor’s purpose was to murder him, called his officers together, harangued them, gained them over, secured the fortifications of Boulogne, and awaited events. Maximian prepared to attack him, but was prevented by a mutiny of the troops. Carausius, who had now the 4th Legion and many other troops, was saluted Emperor, and in September A.D. 288 he crossed the Channel, bringing with him the whole of the fleet. It was the most serious rebellion possible, because it could not be put down so long as Carausius maintained by his fleet the command of the sea. It may be doubted whether the joy of London which Dr. Stukeley sees recorded on the coins in consequence of this arrival was real or only official. One thing is certain, there had been a revolt in Britain on account of the tyranny of the Roman Præfect. This was put down, but not by Carausius. He did not enter the country as its conqueror, in which case his welcome would not have been joyous: he was the enemy of the Emperor, as represented by the tyrannical Præfect; and he was a fellow-countryman. National pride was probably appealed to, and with success, and63 on these grounds a demonstration of joy was called for. The first coin struck by the usurper shows Britannia, with the staff emblematic of merchandise, grasping the hand of the Emperor in welcome, with the legend “Expectate veni”—“Come thou long desired.” Another coin shows Britannia with a cornucopia and a mercurial staff with the legend “Adventus Aug.” The words “Expectate veni” were used, Dr. Stukeley thinks, to flatter the British claim of Phrygian descent. They were taken from Æneas’s speech in Virgil:—

Perhaps the figure which we have called Britannia may have been meant for Augusta. It is hard to understand why the whole country should be represented by the symbol of trade. On another coin the Emperor’s public entry into London is celebrated. He is on horseback; a spear is in his left hand, and his right hand is raised to acknowledge the acclamations of the people.

Maximian lost no time in raising another fleet, with which, in September 289, a great naval battle was fought, somewhere in the Channel, with the result of Maximian’s complete defeat, and as a consequence the arrangement of terms by which Maximian and Diocletian agreed to acknowledge Carausius as associated with them in the Imperial dignity; it was further agreed that Carausius should defend Britain against the Scots and Picts, and that he should continue to act as Comes littoris Saxonici and should retain Boulogne—the head-quarters of the fleet. The full title of the associated Emperor thus became—

Imp. M. Aur. Val. Carausius Aug.

The name of Aurelius he took from Maximian and that of Valerius from Diocletian as adopted by them.

Coins celebrated the sea victory and the peace. Carausius is represented on horseback as at an ovation; not in a chariot, which would have signified triumph. The legend is “IO X”; that is to say, “Shout ten times.” This was the common cry at acclamations. Thus Martial says of Domitian—

Rursus IO magnos clamat tibi Roma triumphos.

In March 290, Carausius associates with himself his son Sylvius, then a youth of sixteen. A coin is struck to commemorate the event. The legend is “Providentia Aug.”—as shown in appointing a successor.

In the same year Carausius, whose head-quarters had been Clausentum (Bitterne), near Southampton, and London alternately, now marched north and took up his quarters at York, where he began by repairing and restoring the work now called the Cars Dyke.

64

On his return to London he celebrated his success with sports and gladiatorial contests. Coins were struck to commemorate the event. They bear the legend “Victoria Aug.”

In the year A.D. 291, Carausius appointed a British Senate, built many temples and public buildings, and, as usual, struck many coins. On some of these may be found the letters S.C. He completed the Cars Dyke and founded the city of Granta. He also named himself Consul for Britain.

In the year 293 the two Emperors, Diocletian and Maximian, met at Milan and created two Cæsars—Constantius Chlorus, father of Constantine the Great, and Galerius Armentarius. And now the pretence of peace with Carausius was thrown away. Chlorus began operations against him by attacking the Franks and Batavians, allies of Carausius. He also urged the Saxons and sea-board Germans to invade Britain. Carausius easily drove off the pirates, and addressed himself to the more formidable enemy. Chlorus laid siege to Boulogne, which was defended by Sylvius, son of Carausius. The British Emperor himself chased his assailant’s fleet triumphantly along the coasts of Gaul and Spain; he swept the seas; he even entered the Mediterranean, took a town, and struck Greek and Punic coins in celebration. He also struck coins with his wife as Victory sacrificing at an altar, “Victoria Augg.”—the two “g’s” meaning Carausius and his son Sylvius.

In May 295, while the Emperor was collecting troops and ships to meet Constantius Chlorus, he was treacherously murdered by his officer Allectus. Probably his son Sylvius was killed with him.

This is Dr. Stukeley’s account of a most remarkable man. A great deal is perhaps imaginary; on the other hand, the coins, read by one who knows how to interpret coins, undoubtedly tell something of the story as it is related.

The history of Carausius as gathered by other writers from such histories as remain differs entirely from Dr. Stukeley’s reading. It is as follows:—

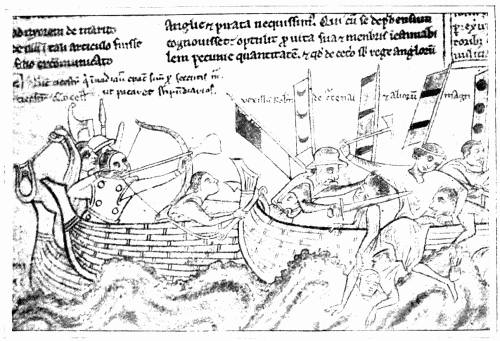

He was of obscure origin, belonged to the Batavian tribe of Menapii; and he began by entering, or being made to enter, the service of the British fleet. The people, afterwards called collectively Saxons, were already actively engaged in piratical descents upon the eastern and the southern coast of Britain. They came over in their galleys; they landed; they pillaged, destroyed, and murdered everywhere within their reach; then they returned, laden with their spoil, to their homes on the banks of the Elbe.

To meet these pirates, to destroy their ships, to make them disgorge their plunder, it was found necessary, in addition to constructing a line of fortresses along the shore—of which Richborough, Bradwell, Pevensey, and Porchester still remain,—to maintain a large and well-formed fleet always in readiness. This was done, and the British fleet, whose head-quarters were at Gesoriacum (Boulogne), was constantly engaged in chasing, attacking, and destroying the pirate vessels.65 It was a service of great danger, but also one which gave a brave man many opportunities of distinction. These opportunities were seized by Carausius, who obtained so great a reputation as a sailor that he was promoted grade after grade until he became Admiral, or Commander of the Fleet.

His courage, which had been shown in a thousand dare-devil, reckless acts, was known to all who manned the galleys; every captain and every cabin-boy could rehearse the exploits of Carausius. Moreover, he had in his hands the power and authority of promotion; he was affable and kindly in his manner; he was, in his way, considerate of the men, whom he rewarded generously for bravery; he was eloquent, too, and understood how to move the hearts of men; his portrait can be seen both full face and profile on his coins, and we can judge that he was a handsome man: in short, he possessed all the gifts wanted to win the confidence, the affection, and the loyalty of soldiers and sailors. With an army—for the service of the fleet was nothing less—at his command, with the example of other usurpers before him, and with the rich and fertile province of Britannia in his power, it is not astonishing that this strong, able man should dream of the Purple.

But first it was necessary to become rich. Without a Treasury the army would melt away. How could Carausius grow rich? By seizing London and pillaging the City? But then he would make the whole island his enemy. There was a better way, a more secret way. He redoubled his vigilance over the coasts, but he did not attack the pirates till they were returning laden with their plunder. He then fell upon them and recaptured the whole. But he did not restore the spoils to their owners: he kept them, and in this way became very quickly wealthy. Presently the peculiar methods of the Admiral began to be talked about; people began to murmur; complaints were sent to Rome. Then Carausius learned that he was condemned to death. He was therefore forced to instant action. He proclaimed himself Emperor with Maximian and Diocletian, and he made an alliance with the Franks.

So long as he could rely on his troops, so long as he was victorious, he was safe; and for a long time there could be no opposition. Britain and the legions then in the island acknowledged him. He crossed over and made his head-quarters at Clausentum (Bitterne), near Southampton. He was certainly some time at London, where he had a mint; and he ruled the country undisturbed for some years.

We know nothing whatever about his rule, but there is probably very little to learn. He kept back the Picts and Scots; he kept back the pirates—that is clear from his coins, which speak of victory. We must remember that the reign of a usurper differed very little from that of a recognised Emperor. He preserved the same administration conducted by the same officers; it was only66 a change of name. Just as the government of France under the Republic is practically the same as that under the Empire, so the province of Britain under Maximian knew no change except a change of proprietor when it passed to Carausius.

But the end came. Carausius had to fight when he was challenged, or die.

The two Emperors appointed two Cæsars. To one, Constantius, was given the Empire of the West. He began his reign by attempting to reduce the usurper. With a large army he advanced north and invested Gesoriacum, where Carausius was lying; next, because the port was then, as it is now, small and narrow and impossible of entrance, except at high tide, he blocked it with stones and piles, so that the fleet could not enter to support him.

It is impossible to know why Carausius did not fight. Perhaps he proposed to gather his troops in Britain and to meet Constantius on British soil. Perhaps he reckoned on Constantius being unable to collect ships in sufficient number to cross the Channel. Whatever his reasons, he embarked and sailed away. The King of the Grove had run away. Therefore his reign was over.

In such cases there is always among the officers one who perceives the opportunity and seizes it. The name of the officer swift to discern and swift to act in this case was Allectus. He murdered the man who had run away, and became himself the King of the Grove.

Very little is known about Allectus or about his rule. Historians speak of him contemptuously as one who did not possess the abilities of Carausius; perhaps, but I cannot find any authority for the opinion. The facts point rather in the opposite direction. At least he commanded the allegiance and the loyalty of the67 soldiers, as Carausius had done; he seems to have kept order in Britain; as nothing is said to the contrary, he must have kept back the Caledonians and Saxons for four years; he maintained the Frankish alliance; and when his time came, his men went out with him to fight, and with him, fighting, fell. In this brief story there is no touch of weakness. One would like to know more about Allectus. Like Carausius, he was a great coiner. Forty of his coins are described by Roach Smith. They represent a manly face of strength and resolution crowned with a coronet of spikes. On the other side is a female figure with the legend “Pax Aug.” Other coins bear the legends “Pietas Aug.,” “Providentia Aug.,” “Temporum felicitas,” and “Virtus Aug.”

He was left undisturbed for nearly four years. Constantius employed this time in collecting ships and men. It is rather surprising that Allectus did not endeavour to attack and destroy those ships in port. When at last the army was in readiness Constantius crossed the Channel, his principal force, under Asclepiodotus, landing on the coast of Sussex. It was said that he crossed with a side wind, which was thought daring, and by the help of a thick fog eluded the fleet of Allectus, which was off the Isle of Wight on the look-out for him.

Allectus was in London: he expected the landing would be on the Kentish coast, and awaited the enemy, not with the view of sheltering himself behind the river, but in order, it would seem, to choose his own place and time for battle.68 Asclepiodotus, however, pushed on, and Allectus, crossing the bridge with his legions, his Frankish allies, and his auxiliaries, went out to meet the enemy. Where did they fight? It has been suggested that Wimbledon was the most likely place. Perhaps. It is quite certain that the battle was very near London, from what followed. I would suggest Clapham Common; but as the whole of that part of London was a barren moorland, flat, overgrown with brushwood, the battle may have taken place anywhere south of Kensington, where the ground begins to rise out of the marsh. We have no details of the battle, which was as important to Britain as that of Senlac later on, for the invader was successful. The battle went against Allectus, who was slain in the field. His routed soldiers fled to London, and there began to sack the City and to murder the people. Constantius himself at this moment arrived with his fleet, landed his troops, and carried on a street fight with the Franks until every man was massacred. Two facts come out clearly: that the battle was fought very near to London; and that when Allectus fell there was left neither order nor authority.

This is the third appearance of London in history. In the first, A.D. 61, Tacitus speaks of it, as we have seen, as a City of considerable trade; in the second, the rebellion of Boadicea, it furnishes the third part of the alleged tale of 70,000 victims; at this, the third, the defeated troops are ravaging and plundering the helpless City. In all three appearances London is rich and thickly populated.

We may also remark that we have now arrived at the close of the third century, and that, so far, there has been very little rest or repose for the people, but rather continued fighting from the invasion of Aulus Plautius to the defeat of Allectus.

It is true that the conscription of the British youth carried them out of the country to serve in other parts of the Roman Empire; it is also true that the fighting in Britain was carried on by the legions and the auxiliaries, and that the Lex Julia Majestatis disarmed the people subject to Roman rule. Looking, however, to the continual fighting on the frontier and the fighting in the Channel, and the incursions of the Scots and Picts, one cannot believe that none of the British were permitted to fight in defence of their own land, or to man the fleet which repelled the pirate. Those who speak of the enervating effects of the long peace under the Roman rule—the Pax Romana—would do well to examine for themselves into the area covered by this long peace and its duration.

It was not in London, but at York, that Constantius fixed his residence, in order to restrain the Picts and Scots. The importance attached to Britain may be inferred from the fact that the Emperor remained at York until his death in A.D. 306, when his son, Constantine the Great, succeeded him, and continued in the island, probably at York, for six years. Coins of Constantine and also of his mother, Helena, have been found in London.

69

In the year 310, Constantine quitted the island. A period of nearly forty years, concerning which history is silent, followed. This time may have been one of peace and prosperity.

The government of the country had been completely changed by the scheme of defence introduced by Diocletian and modified by Constantine. Under that scheme the Roman world was to be governed by two Emperors—one on the Danube, and the other in the united region of Spain, Gaul, and Britain. The island was divided into five provinces of Britannia Prima and Britannia Secunda; Lower Britain became Flavia Cæsariensis and Maxima Cæsariensis; between the walls of Hadrian and Antoninus was the Province of Valentia. Each province had its own Vicarius or Governor, who administered his province in all civil matters.

The Civil Governor of Britain was subject to the Præfectus of Gaul, who resided at Treviri (Treves) or Arelate (Arles). He was called Vicarius, and had the title Vir Spectabilis (your Excellency). His head-quarters were at York. The “Civil Service,” whose officers lived also in the fort, consisted of a Chief Officer (Princeps), a Chief Secretary (Cornicularis), Auditors (Numerarii), a Commissioner of Prisons (Commentariensis), Judges, Clerks, Serjeants, and other officers. For the revenues there were a Collector (Rationalis summarum Britanniarum), an Overseer of Treasure (Præpositus Thesaurorum). In the hunting establishment there were Procuratores Cynegiorum. The military affairs of the state were directly under the control of the Præfect of Gaul. The Vicarius had no authority in things military. We have seen also how one general after another fixed his head-quarters, not in London, but at York, or elsewhere. London played a much less important part than York in the military disposition of the island. There were three principal officers: the Count of the Saxon Shore (Comes littoris Saxonici), the Count of Britain, and the Duke of Britain. The first of these had the command of the fleet—Carausius, we have seen, was Comes littoris Saxonici—with the charge of the nine great fortresses established along the coast from Porchester to Brancaster. The Duke of Britain had his head-quarters at York, with the command of the 6th Legion and charge of the wall. It is not certain where were the head-quarters of the Count of Britain. Each of these officers, like the Vicarius, had his own establishment. The permanent forces in Great Britain were estimated at four, afterwards two, legions with auxiliaries, the whole amounting to 19,200 infantry and 1700 cavalry. Surely a force capable of repelling the incursions of Irish, Scots, and Saxons all together!

It is not possible to estimate the effect upon the country of these military settlements; we do not know either the extent of the territory they occupied or the number of the settlers at any colony. Britannia is a large island, and many such settlements may have been made without any effect upon the country. One thing, however, is certain, that foreign settlers when they marry women belong70ing to their new country very speedily adopt the manners and the language of that country, and their children belong wholly to their mother’s race. Thus Germans and Scandinavians settling in America and marrying American women adapt themselves to American manners and learn the English tongue, while their children, taught in the public schools, are in no respect to be accounted different from the children of pure American parentage. Even the most marked and most bigoted difference of religion does not prevent this fusion. The Polish Jew becomes in the second generation an Englishman in England, or an American in America. And in Ireland, when the soldiers of Cromwell settled in County Kerry and married women of the country, their children became Irish in manners and in thought. The descendants of those soldiers have nothing left from their great-grandfathers—not religion, not manners, not Puritan ideas—nothing but their courage.

So that one can neither affirm nor deny that these settlers in any way influenced or changed the general character of the people. Religion would be no hindrance, because all the ancient religions admitted the gods of all people. It is sufficient to note the fact, and to remember that the people so called Britons were after four hundred years of Roman rule as mixed a race as could well be found. In London the mixture was still greater, because the trade of Roman London at its best was carried on with the whole habitable world.

The language spoken among the better sort—the language of the Court, the Forum, and the Port—was undoubtedly Latin. All the inscriptions are in Latin; none are in Celtic. The language of the common people of London was like that of the modern pidgin-English, a patois composed of Latin without its trappings of inflexions and declensions—such a patois as that from which sprang Mediæval French and Provençal, mixed with words from every language under the sun: words brought to the Port by sailors who still preserved the Phœnician tongue; by Greeks from Massilia; by Italians from Ostia and Brundusium; by Norsemen from Gotland and the Baltic; by Flemings, Saxons, and Germans.

The legionaries contributed their share to the patois as spoken by the country folk. But there were few soldiers in the fort of Augusta; the London dialect, except among the slaves working at the Port or waiting in their barracoons to be exported for the gladiatorial contests, was pidgin-Latin.

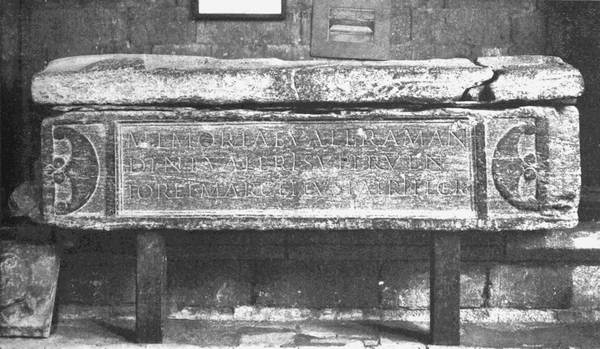

The Emperor Constans came over in 347. He was murdered, three years after leaving this country, by Magnentius, a native of Britain. The rise and fall of this pretender involved the ruin of many of his own countrymen and the soldiers of the Roman occupation. One Paulus, surnamed Catena, was sent to London in order to punish the adherents of Magnentius. Then follows a very singular story. The cruelties of Paulus excited the deepest indignation, insomuch that the Civil Governor of the province, the “Vicarius,” Martinus by name, endeavoured to interpose on71 behalf of the victims. Failing to move the judge to mercy, he tried to save his friends by murdering him. When this attempt also failed, he committed suicide. Paulus returned to Rome, carrying with him a multitude of prisoners, who were tortured, imprisoned, executed, or exiled.

The Picts and Scots took advantage of the disorder to invade the country after the departure of Paulus. It is evident that the regular troops had been withdrawn or were in confusion, because troops were brought over from Gaul to drive back the invaders.

Some ten years later the Picts and Scots renewed their attacks. They defeated and slew the Count of the Saxon Shore, and they defeated the Duke of Britain. The Emperor Valentinian therefore sent Theodosius with a very large force into the island. He found the enemy ravaging the country round London—it was probably at this period, and in consequence of the repeated invasions from the north, that the wall of London was built. In another place will be found an account of the wall. It is sufficient to state here, that it was most certainly built in a great hurry and apparently at a time of panic, because stones in the City—from public buildings, the temples, the churches, and cemeteries—were seized wherever possible and built up in the wall.

72

However, Theodosius drove back the invaders with great slaughter. He found that there were many of the native population with the enemy. He adopted a policy of conciliation: he relieved the people of their heavy taxation, and rebuilt their cities and fortresses.

Here follows an incident which illustrates at once the dangers of the time and the wisdom of Theodosius. I quote it from Wright (The Celt, the Roman, and the Saxon, 1852 edition, p. 378):—

“There was in Britain at this time a man named Valentinus, a native of Valeria, in Pannonia, notorious for his intrigues and ambition, who had been sent as an exile to Britain in expiation of some heavy crime. This practice of banishing political offenders to Britain appears to have been, at the time of which we are now speaking, very prevalent; for we learn from the same annalist, that a citizen of Rome, named Frontinus, was at the time of the revolt just described sent into exile in Britain for a similar cause. Men like these no sooner arrived in the island than they took an active part in its divisions, and brought the talent for political intrigue which had been fostered in Italy to act upon the agitation already existing in the distant province. Such was the case with Valentinus, who, as the brother-in-law of one of the deepest agitators of Rome, the vicar Maximinus (described by Ammianus as ille exitialis vicarius), had no doubt been well trained for the part he was now acting. As far as we can gather from the brief notices of the historian, this individual seems, when Theodosius arrived in Britain, to have been actively engaged in some ambitious designs, which the arrival of that great and upright commander rendered hopeless. Theodosius had not been long in Londinium when he received private information that Valentinus was engaged with the other exiles in a formidable conspiracy, and that even many of the military had been secretly corrupted by his promises. With the vigour which characterised all his actions, Theodosius caused the arch-conspirator and his principal accomplices to be seized suddenly, at the moment when their designs were on the point of being carried into execution, and they were delivered over to Duke Dulcitius, to receive the punishment due to their crimes; but, aware of the extensive ramifications of the plot in which they had been engaged, and believing that it had been sufficiently crushed, Theodosius wisely put a stop to all further inquiries, fearing lest by prosecuting them he might excite an alarm which would only bring a renewal of the scenes of turbulence and outrage which his presence had already in a great measure appeased. The prudence as well as the valour of Theodosius were thus united in restoring Britain to peace and tranquillity; and we are assured that when, in 369, he quitted the island, he was accompanied to the port where he embarked by crowds of grateful provincials.”

In the year 383 Britain furnished another usurper or claimant of the people, in the person of Magnus Maximus. He was a native of Spain, who had served in Britain with great distinction, and was a favourite with the soldiers. Now the73 troops then stationed in Britain are stated by the historian to have been the most arrogant and turbulent of all the Imperial troops.

The career of Maximus, and his ultimate defeat and death at Aquileia, belong to the history of the Roman Empire.

One of the officers of Theodosius, named Chrysanthus, who afterwards became a bishop at Constantinople, pacified Britain—one hopes by methods less brutal than those of Paulus Catena.

The people, however, had little to congratulate themselves upon. Their country with its five provinces was regarded as a department of the Court of Treves. When there was any trouble in the Empire of the West, the legions of Great Britain were withdrawn without the least regard for the defence of the country against the Picts and Scots; and the division into provinces was a source of weakness. Moreover, the general decay of the Empire was accompanied by the usual signs of anarchy, lawlessness, and oppression. The troops were unruly and mutinous; time after time, as we have seen, they set up one usurper and murdered another; they were robbed by their officers; their pay was irregular. The complexity of the new system added to the opportunities of the taxing authorities and the tax-collector. The visit of the Imperial tax-gatherers was worse than the sack of a town by the enemy. Torture was freely used to force the people to confess their wealth; son informed against father, and father against son; they were taxed according to confessions extorted under torture.

The end of the Roman occupation, however, was rapidly approaching. Theodosius died in 395, and left his Western dominions to Honorius. There were still two legions in Britain: the 6th, at Eboracum (York); and the 2nd, at Rutupiæ (Richborough). There were also numerous bodies of auxiliaries. Early in the fifth century these soldiers revolted and set up an Emperor of their own, one Marcus. They murdered him in 407, and set up another named Gratian, whom they also murdered after a few months, when they chose an obscure soldier on account of his name, Constantine.

He at once collected his army and crossed over to Gaul. His subsequent career, like that of Maximus, belongs to the history of Rome.

It would appear that the withdrawal of the legions by Constantine was the actual end of the Roman occupation. The cities of Britain took up arms to repel invasion from the north and the descent of the pirates in the west, and in 410 received letters from Honorius telling them to defend themselves.

The story told by Gildas is to the effect that Maximus took away all the men capable of bearing arms; that the cities of Britain suffered for many years under the oppression of the Picts and Scots; that they implored the Romans for help; and that Roman legions came over, defeated the Picts and Scots, and taught the Britons how to build a wall. This is all pure legend.

74

The commonly received history of the coming of the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons is chiefly legendary. It is impossible to arrive at the truth, save by conjecture from a very few facts ascertained. Thus it is supposed that the Saxons began, just as the Danes did four hundred years afterwards, by practical incursions leading to permanent settlements; that the words littus Saxonicum signified, not the shore exposed to Saxon pirates, but the shore already settled by Saxons; that in some parts the transition from Roman to Saxon was gradual; that the two races mixed together—at Canterbury, Colchester, Rochester, and other places we find Roman and Saxon interments in the same cemetery; that the Saxons had gained a footing in the island long before the grand invasions of which the Saxon Chronicle preserves the tradition.

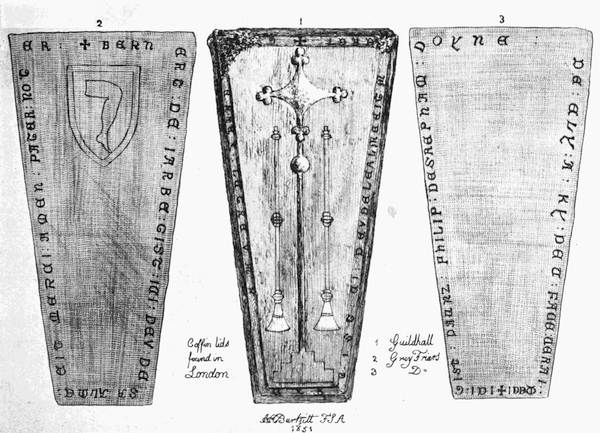

This long history of warfare, of civil commotion, of mutiny and usurpation, of conscription and taxation, is not a pleasant picture of Britain under the famous Pax Romana. How did the City of London fare? It was the residence of the Proprætor before the new scheme of Diocletian. This is proved by the discovery of certain inscribed tiles. These tiles record the legions or the officers stationed in various places. At Chester they bear the name of the 20th Legion; at York, those of the 6th and the 9th. At Lymne and Dover the usual inscription is Cl.Br., supposed to mean Classiarii Britannici. Some of the tiles above referred to are inscribed PRB. Lon., or PPBR. Lon., or P.PR.BR. Roach Smith reads these letters Prima Cohors Britanniæ Londinii, and assumes that the first British Cohort was once stationed in London. Wright, however, reads Proprætor Britanniæ Londinii, thus showing that London was the seat of government. As there is no hint elsewhere that the first British Cohort served in Britain, but plenty of evidence as to its being elsewhere, as in Egypt and Germany, Wright’s interpretation is probably the correct one.

Except for the attempted sack of the City after the defeat of Allectus and for the sanguinary revenge by Paulus Catena, London seems to have been but little disturbed by the invasions and the mutinies and the usurpations. Her trade went on. In bad times, as when Magnentius or Maximus drew off the soldiers, and the invaders fell upon the country on the north, the east, and the west, destroying the towns and laying waste the country, London suffered. In the intervals of peace her wharves were crowded with merchandise and her port with ships.

The introduction of Christianity into London, as into Britain generally, began, there can be little doubt, in the second century. The new religion, however, made very slow progress. The first missionaries, believed to have been St. Paul or St. Joseph of Arimathæa, with Lazarus and his two sisters, were probably converts from Gaul who came to Britain in pursuit of their ordinary business. In the year 208 Tertullian mentions the existence of Christians in Britain. Early in the fourth century there were British Bishops at the Council of Arles.

75

In 324 Christianity was recognised as the religion of the State.

In the year 325 the British Church assented to the conclusions of the Council of Nicæa. In 386 there was an Established Christian Church in Britain, in habitual intercourse with Rome. As to the reality of the Christianity of the people and how far it was mixed up with remains of Mithraism and the ancient faiths of Rome and Gallia, we have no means of judging.

What was the government of London itself at this time? We can find an answer in the constitution of other Roman towns. London never became a municipium—a town considered by the Imperial authorities as of the first importance. There were only two towns of this rank in Britain, viz. Eboracum (York) and Verulam (St. Alban’s). It was, with eight other towns, a colonia. Wright16 is of opinion that there was very little difference in later times between the colonia and the municipium. These towns enjoyed the civitas or rights of Roman citizens; they consisted of the town and certain lands round it; and they had their own government exempt from the control of the Imperial officers. In that case the forum would not necessarily be placed in the fort or citadel, which was the residence of the Vicarius when he was in London with his Court and establishment. At the same time this citadel occupied an extensive area, and the City being without walls till the year 360 or thereabouts, all the public buildings were within that area. The governing body of the City was called the curia, and its members were curiales, decuriones, or senators; the rank was hereditary, but, like every hereditary house, it received accessions from below. The two magistrates, the duumviri, were chosen yearly by the curia from their own body. A town council, or administrative body, was also elected for a period of fifteen years by the curiales from their own body; the members were called principales. The curia appointed, also, all the less important officers; in fact it controlled the whole municipality. The people were only represented by one officer, the defensor civitatis, whose duty it was to protect his class against tyrannical or unjust usurpations of power by the curiales. No one could be called upon to serve as a soldier except in defence of his own town. The defence of the Empire was supposed to be taken over by the Emperor himself. Let every man, he said, rest in peace and carry on his trade in security. But when the Emperor’s hands grew weak, what had become of the martial spirit? The existence of this theory explains also how the later history of the Roman Empire is filled with risings and mutinies and usurpations, not of cities and tribes, but of76 soldiers. At the same time, since we read of the British youth going off to fight in Germany and elsewhere, the country lads had not lost their spirit.17 The people of London itself, however, may have become, like those of Rome, unused to military exercises. Probably there was no fear of any rising in London, and there was not a large garrison in the citadel. The citizens followed their own trade, unarmed, like the rest of the world; even their young men were not necessarily trained to sports and military exercises. Their occupations were very much the same as those of later times: there were merchants, foreign and native, ship-builders and ship-owners, sailors, stevedores and porters, warehousemen, clerks, shopmen, lawyers, priests, doctors, scribes, professors and teachers, and craftsmen of all kinds. These last had their collegia or guilds, each with a curialis for a patron. The institution is singularly like the later trade guilds, each with a patron saint. One would like to think that a craft company, such as the blacksmiths’, has a lineal descent from the Collegium Fabrorum of Augusta. But as will be proved later on, that is impossible. London was a city of trade, devoted wholly to trade. The more wealthy sort emulated the luxury and effeminacy of the Roman senators—but only so long as the Empire remained strong. When one had to fight or be robbed, to fight or to be carried off in slavery, to fight or to die, there was an end, I believe, of the effeminacy of the London citizens.

Let us consider this question of the alleged British effeminacy. We have to collect the facts, as far as we can get at them, which is a very little way, and the opinion of historians belonging to the time.

Gildas, called Sapiens, the Sage—in his Book of Exclamations,—speaks thus contemptuously of his own people:—

1. The Romans, he says, on going away, told the people that “inuring themselves to warlike weapons, and bravely fighting, they should valiantly protect their country, their property, wives and children, and what is dearer than these, their liberty and lives; that they should not suffer their hands to be tied behind their backs by a nation which, unless they were enervated by idleness and sloth, was not more powerful than themselves, but that they should arm those hands with buckler, sword, and spear, ready for the field of battle.

2. He says: “The Britons are impotent in repelling foreign foes, but bold and invincible in raising civil war, and bearing the burdens of their offences; they are impotent, I say, in following the standard of peace and truth, but bold in wickedness and falsehood.”

3. He says: “To this day”—many years after the coming of the Saxons—“the cities of our country are not inhabited as before, but being forsaken and overthrown, lie desolate, our foreign wars having ceased, but our civil troubles still remaining.”

Bede, who writes much later, thus speaks, perhaps having read the evidence77 of Gildas: “With plenty, luxury increased, and this was immediately attended with all sorts of crimes: in particular, cruelty, hatred of truth, and love of falsehood: insomuch that if any one among them happened to be milder than the rest, and inclined to truth, all the rest abhorred and persecuted him, as if he had been the enemy of his country. Nor were the laity only guilty of these things, but even our Lord’s own flock and His pastors also addicted themselves to drunkenness, animosity, litigiousness, contention, envy, and other such-like crimes, and casting off the light yoke of Christ. In the meantime, on a sudden, a severe plague fell upon that corrupt generation, which soon destroyed such numbers of them that the living were scarcely sufficient to bury the dead; yet those who survived could not be drawn from the spiritual death which their sins had incurred either by the death of their friends or the fear of their own.” This declaration of wickedness is written, one observes, ecclesiastically—that is, in general terms.

The opinion of an ecclesiastic who, like Gildas, connects morals and bravery,

and finds in a king’s alleged incontinence the cause of internal disasters, may be

taken for what it is worth. One undeniable fact remains, that for two hundred

years this effeminate people fought without cessation or intermission for their lives

and their liberties. Two hundred years, if you think of it, is a long time for an

effeminate folk to fight. Deprived of their Roman garrison, they armed themselves;

deprived of a government which had kept order for four hundred years, they

elected their own governors; unfortunately their cities were separate, each with

its own mayor (comes civitatis). They fought against the wild Highlander from

the north; against the wild mountain man from the west; against the wild Irish78

from over the western sea; against the wild Saxon and Dane from the east. They

were attacked on all sides; they were driven back slowly: they did nothing but

fight during the whole of that most wretched period while the Roman Empire

fell to pieces. When all was over, some of the survivors were found in the Welsh

mountains; some in the Cumbrian Hills; some in the Fens; some beyond the

great moor of Devon; some in the thick forests of Nottingham, of Middlesex, of

Surrey, and of Sussex. Most sad and sorrowful spectacle of all that sad and

sorrowful time is one picture—it stands out clear and distinct. I see a summer day

upon the southern shore and in the west of England; I think that the place is

Falmouth. There are assembling on the sea-shore a multitude of men, women,

and children. Some of them are slaves; they are tied together. It is a host of

many thousands. Close to the shore are anchored or tied up a vast number of ships

rudely and hastily constructed, the frame and seats of wood, the sides made out of

skins of creatures sewn together and daubed with grease to keep out the water.

The ships are laden with provisions; some of them are so small as to be little

better than coracles. And while the people wait, lo! there rises the sound of far-off

voices which chant the Lamentation of the Psalmist. These are monks who

are flying from the monastery, taking with them only their relics and their treasures.

See! they march along bearing the Cross and their sacred vessels, singing as they

go. So they get on board; and then the people after them climb into their vessels.

They set their sails; they float down the estuary and out into the haze beyond

and are lost. In this

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content