Search london history from Roman times to modern day

17

It is due to the respect with which all writers upon London must regard the first surveyor and the collector of its traditions and histories that we should quote his words as to the origin and foundation of the City. He says (Strype’sStow, vol. i. book i.):—

“As the Roman Writers, to glorify the City of Rome, drew the Original thereof from Gods, and Demi-gods, so Geoffrey of Monmouth, the Welsh historian, deduceth the Foundation of this famous City of London, for the greater Glory thereof, and Emulation of Rome, from the very same original. For he reporteth, that Brute, lineally descended from the Demi-god Eneas, the son of Venus, Daughter of Jupiter, about the Year of the World 2855, and 1108 before the Nativity of Christ, builded the City near unto the River now called Thames, and named it Troynovant, or Trenovant. But herein, as Livy, the most famous Historiographer of the Romans, writeth, ‘Antiquity is pardonable, and hath an especial Privilege, by interlacing Divine Matters with Human, to make the first Foundations of Cities more honourable, more Sacred, and as it were of greater Majesty.’

This Tradition concerning the ancient Foundation of the City by Brute, was of such Credit, that it is asserted in an ancient Tract, preserved in the Archives of the Chamber of London; which is transcribed into the Liber Albus, and long before that by Horn, in his old Book of Laws and Customs, called Liber Horn. And a copy of this Tract was drawn out of the City Books by the Mayor and Aldermen’s special Order, and sent to King Henry the VI., in the Seventh year of his reign; which Copy yet remains among the Records of the Tower. The Tract is as followeth:—

18

‘Inter Nobiles Urbes Orbis, etc. 1. Among the noble Cities of the World which Fame cries up, the City of London, the only Seat of the Realm of England, is the principal, which widely spreads abroad the Rumour of its Name. It is happy for the Wholesomeness of the Air, for the Christian religion, for its most worthy Liberty, and most ancient Foundation. For according to the Credit of Chronicles, it is considerably older than Rome: and it is stated by the same Trojan Author that it was built by Brute, after the Likeness of Great Troy, before that built by Romulus and Remus. Whence to this Day it useth and enjoyeth the ancient City Troy’s Liberties, Rights, and Customs. For it hath a Senatorial Dignity and Lesser Magistrates. And it hath Annual Sheriffs instead of Consuls. For whosoever repair thither, of whatsoever condition they be, whether Free or Servants, they obtain there the refuge of Defence and Freedom. Almost all the Bishops, Abbots, and Nobles of England are as it were Citizens and Freemen of this City, having their noble Inns here.’

These and many more matters of remark, worthy to be remembered, concerning this most noble City, remain in a very old Book, called Recordatorium Civitatis; and in the Book called Speculum.

King Lud (as the same Geoffrey of Monmouth noteth) afterward (about 1060 Years after) not only repaired this City, but also increased the same with fair Buildings, Towers, and Walls; which after his own Name called it Caire-Lud, or Luds-Town. And the strong Gate which he builded in the west Part of the City, he likewise, for his own honour, named Ludgate.

And in Process of Time, by mollifying the Word, it took the Name of London, but some others will have it called Llongdin; a British word answering to the Saxon word Shipton, that is, a Town of Ships. And indeed none hath more Right to take unto itself that Name of Shipton, or Road of Ships, than this City, in regard of its commodious situation for shipping on so curious a navigable River as the Thames, which swelling at certain Hours with the Ocean Tides, by a deep and safe Channel, is sufficient to bring up ships of the greatest Burthen to her Sides, and thereby furnisheth her inhabitants with the Riches of the known World; so that as her just Right she claimeth Pre-eminency of all other Cities. And the shipping lying at Anchor by her Walls resembleth a Wood of Trees, disbranched of their Boughs.

This City was in no small Repute, being built by the first Founder of the British Empire, and honoured with the Sepulchre of divers of their Kings, as Brute, Locrine, Cunodagius, and Gurbodus, Father of Ferrex and Porrex, being the last of the Line of Brute.

Mulmutius Dunwallo, son of Cloton, Duke of Cornwall, having vanquished his Competitors, and settled the Land, caused to be erected on, or near the Place, where now Blackwell-Hall standeth (a Place made use of by the Clothiers for the sale of their Cloth every Thursday), a Temple called the Temple of Peace; and after his Death was there interred. And probably it was so ordered to gratify the Citizens, who favoured his Cause.

Belinus (by which Name Dunwallo’s Son was called) built an Haven in this Troynovant, with a Gate over it, which still bears the Name of Belingsgate [now Billingsgate]. And on the Pinnacle was a brazen Vessel erected, in which was put the ashes of his Body burnt after his Death.

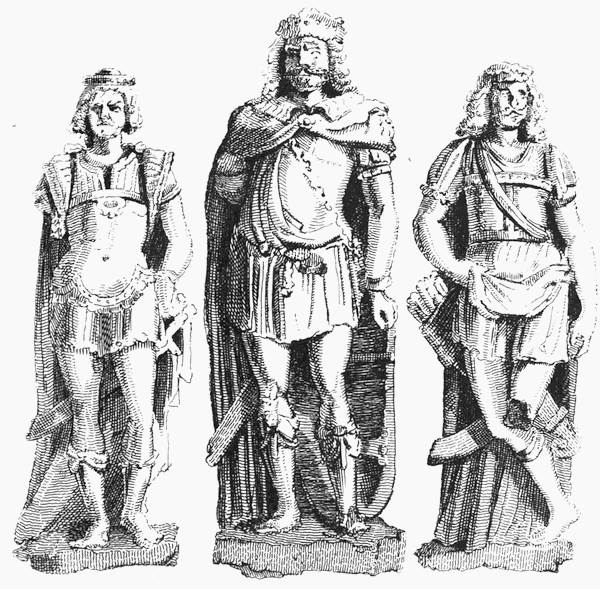

The said Belinus is supposed to have built the Tower of London, and to have19 appointed three Chief Pontiffs to superintend all Religious Affairs throughout Britain; whereof one had his See in London, and the other Sees were York and Carleon. But finding little on Record concerning the actions of those Princes, until we come to the reign of King Lud, it is thought unnecessary to take any further Notice of them. He was eldest son of Hely, who began his Reign about 69 years before the Birth of Jesus Christ. A Prince much praised by Historians for his great Valour, noble Deeds, and Liberality (for amending the Laws of the Country, and forming the State of his Common-weal). And in particular, for repairing this City, and erecting many fair Buildings, and encompassing it about with a strong stone Wall. In the west Part whereof he built a strong Gate, called Ludgate, as was shewed before, where are now standing in Niches, over the said Gate, the Statues of this good King, and his two Sons on each side of him, as a lasting Monument of his Memory, being, after an honourable Reign, near thereunto Buried, in a Temple of his own Building.

This Lud had two Sons, Androgeus and Theomantius [or Temanticus], who being not of age to govern at the death of their father, their Uncle Cassivelaune took upon him the Crown; about the eighth Year of whose reign, Julius Cæsar arrived in this Land, with a great power of Romans to conquer it. The Antiquity20 of which conquest, I will summarily set down out of his own Commentaries, which are of far better credit than the Relations of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The chief Government of the Britons, and Administration of War, was then by common advice committed to Cassivelaune, whose borders were divided from the Cities on the sea coast by a river called Thames, about fourscore miles from the sea. This Cassivelaune before had made continual Wars with the other Cities; but the Britons, moved with the coming of the Romans, had made him their Sovereign and General of their Wars (which continued hot between the Romans and them). [Cæsar having knowledge of their intent, marched with his army to the Thames into Cassivelaune’s Borders. This River can be passed but only in one place on Foot, and that with much difficulty. When he was come hither, he observed a great power of his enemies in Battle Array on the other side of the River. The Bank was fortified with sharp stakes fixed before them; and such kind of Stakes were also driven down under water, and covered with the river. Cæsar having understanding thereof by the Prisoners and Deserters, sent his Horse before, and commanded his Foot to follow immediately after. But the Roman Soldiers went on with such speed and force, their Heads only being above water, that the Enemy not being able to withstand the Legions, and the Horse, forsook the Bank and betook themselves to Flight. Cassivelaune despairing of Success by fighting in plain battle, sent away his greater forces, and keeping with him about Four Thousand Charioteers, watched which way the Romans went, and went a little out of the way, concealing himself in cumbersome and woody Places. And in those Parts where he knew the Romans would pass, he drove both Cattle and People out of the open Fields into the Woods. And when the Roman Horse ranged too freely abroad in the Fields for Forage and Spoil, he sent out his Charioteers out of the Woods by all the Ways and Passages well known to them, and encountered with the Horse to their great Prejudice. By the fear whereof he kept them from ranging too far; so that it came to this pass, that Cæsar would not suffer his Horse to stray any Distance from his main Battle of Foot, and no further to annoy the enemy, in wasting their Fields, and burning their Houses and Goods, than their Foot could effect by their Labour or March.]

But in the meanwhile, the Trinobants, in effect the strongest City of those Countries, and one of which Mandubrace, a young Gentleman, that had stuck to Cæsar’s Party, was come to him, being then in the Main Land [viz. Gaul], and thereby escaped Death, which he should have suffered at Cassivelaune’s Hands (as his Father Imanuence who reigned in that city had done). The Trinobants, I say, sent their Ambassadors, promising to yield themselves unto him, and to do what he should command them, instantly desiring him to protect Mandubrace from the furious tyranny of Cassivelaune, and to send some into the City, with authority to take the Government thereof. Cæsar accepted the offer and appointed them to21 give him forty Hostages, and to find him Grain for his Army, and so sent he Mandubrace to them. They speedily did according to the command, sent the number of Hostages, and the Bread-Corn.

When others saw that Cæsar had not only defended the Trinobants against Cassivelaune, but had also saved them harmless from the Pillage of his own Soldiers, the Cenimagues, the Segontiacs, the Ancalites, the Bibrokes, and the Cassians, by their Ambassies, yield themselves to Cæsar. By these he came to know that Cassivelaune’s Town was not far from that Place, fortified with Woods and marshy Grounds; into the which a considerable number of Men and Cattle were gotten together. For the Britains call that a Town, saith Cæsar, when they have fortified cumbersome Woods, with a Ditch and a Rampire; and thither they are wont to resort, to abide the Invasion of their Enemies. Thither marched Cæsar with his Legions. He finds the Place notably fortified both by Nature and human Pains; nevertheless he strives to assault it on two sides. The Enemies, after a little stay, being not able longer to bear the Onset of the Roman Soldiers, rushed out at another Part, and left the Town unto him. Here was a great number of Cattle found, and many of the Britains were taken in the Chace, and many slain.

While these Things were doing in these Quarters, Cassivelaune sent Messengers to that Part of Kent, which, as we showed before, lyeth upon the Sea, over which Countries Four Kings, Cingetorix, Caruil, Taximagul, and Segorax, reigned, whom he commanded to raise all their Forces, and suddenly to set upon and assault their Enemies in their Naval Trenches. To which, when they were come, the Romans sallied out upon them, slew a great many of them, and took Cingetorix, an eminent Leader among them, Prisoner, and made a safe Retreat. Cassivelaune, hearing of this Battle, and having sustained so many Losses, and found his Territories wasted, and especially being disturbed at the Revolt of the Cities, sent Ambassadors along with Comius of Arras, to treat with Cæsar concerning his Submission. Which Cæsar, when he was resolved to Winter in the Continent, because of the sudden insurrection of the Gauls, and that not much of the Summer remained, and that it might easily be spent, accepted, and commands him Hostages, and appoints what Tribute Britain should yearly pay to the People of Rome, giving strait Charge to Cassivelaune, that he should do no Injury to Manubrace, nor the Trinobants. And so receiving the Hostages, withdrew his Army to the Sea again.

Thus far out of Cæsar’s Commentaries concerning this History, which happened in the year before Christ’s Nativity LIV. In all which Process, there is for this Purpose to be noted, that Cæsar nameth the City of the Trinobantes; which hath a Resemblance with Troynova or Trenovant; having no greater Difference in the Orthography than the changing of [b] into [v]. And yet maketh an Error, which I will not argue. Only this I will note, that divers learned Men do not think Civitas Trinobantum to be well and truly translated The City of the Trinobantes: but that22 it should rather be The State, Communalty, or Seignory of the Trinobants. For that Cæsar, in his Commentaries, useth the Word Civitas only for a People living under one and the self-same Prince and Law. But certain it is, that the Cities of the Britains were in those Days neither artificially builded with Houses, nor strongly walled with Stone, but were only thick and cumbersome Woods, plashed within and trenched about. And the like in effect do other the Roman and Greek authors directly affirm; as Strabo, Pomponius Mela, and Dion, a Senator at Rome (Writers that flourished in the several Reigns of the Roman Emperors, Tiberius, Claudius, Domitian, and Severus): to wit, that before the Arrival of the Romans, the Britains had no Towns, but called that a Town which had a thick entangled Wood, defended, as I said, with a Ditch and Bank; the like whereof the Irishmen, our next Neighbours, do at this day call Fastness. But after that these hither Parts of Britain were reduced into the Form of a Province by the Romans, who sowed the Seeds of Civility over all Europe, this our City, whatsoever it was before, began to be renowned, and of Fame.

For Tacitus, who first of all Authors nameth it Londinium, saith, that (in the 62nd year after Christ) it was, albeit, no Colony of the Romans; yet most famous for the great Multitude of Merchants, Provision and Intercourse. At which time, in that notable Revolt of the Britains from Nero, in which seventy thousand Romans and their Confederates were slain, this City, with Verulam, near St. Albans, and Maldon, then all famous, were ransacked and spoiled.

For Suetonius Paulinus, then Lieutenant for the Romans in this Isle, abandoned it, as not then fortified, and left it to the Spoil.

Shortly after, Julius Agricola, the Roman Lieutenant in the Time of Domitian, was the first that by exhorting the Britains publickly, and helping them privately, won them to build Houses for themselves, Temples for the Gods, and Courts for Justice, to bring up the Noblemen’s Children in good Letters and Humanity, and to apparel themselves Roman-like. Whereas before (for the most part) they went naked, painting their Bodies, etc., as all the Roman Writers have observed.

True it is, I confess, that afterward, many Cities and Towns in Britain, under the Government of the Romans, were walled with Stone and baked Bricks or Tiles; as Richborough, or Rickborough-Ryptacester in the Isle of Thanet, till the Channel altered his Course, besides Sandwich in Kent, Verulamium besides St. Albans in Hertfordshire, Cilcester in Hampshire, Wroxcester in Shropshire, Kencester in Herefordshire, three Miles from Hereford Town; Ribchester, seven Miles above Preston, on the Water of Rible; Aldeburg, a Mile from Boroughbridge, on Watheling-Street, on Ure River, and others. And no doubt but this our City of London was also walled with Stone in the Time of the Roman Government here; but yet very latewardly; for it seemeth not to have been walled in the Year of our Lord 296. Because in that Year, when Alectus the Tyrant was slain in the Field,23 the Franks easily entered London, and had sacked the same, had not God of his great Favour at that very Instant brought along the River of Thames certain Bands of Roman Soldiers, who slew those Franks in every Street of the City.”

We need not pursue Stow in the legendary history which follows. Let us next turn to the evidence of ancient writers. Cæsar sailed for his first invasion of Britain on the 26th of August B.C. 55. He took with him two legions, the 7th and the 10th. He had previously caused a part of the coast to be surveyed, and had inquired of the merchants and traders concerning the natives of the island. He landed, fought one or two battles with the Britons, and after a stay of three weeks he retired.

The year after he returned with a larger army—an army of five legions and 2000 cavalry. On this occasion he remained four months. We need not here inquire into his line of march, which cannot be laid down with exactness. After his withdrawal certain British Princes, when civil wars drove them out, sought protection of Augustus. Strabo says that the island paid moderate duties; that the people imported ivory necklaces and bracelets, amber, and glass; that they exported corn, cattle, gold and silver, iron, skins, slaves, and hunting-dogs. He also says that there were four places of transit from the coast of Gaul to that of Britain, viz. the mouths of the Rhine, the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne.

The point that concerns us is that there was before the arrival of the Romans already a considerable trade with the island.

Nearly a hundred years later—A.D. 43—the third Roman invasion took place in the reign of the Emperor Claudius under the general Aulus Plautius. The Roman fleet sailed from Gesoriacum (Boulogne), the terminus of the Roman military road across Gaul, and carried an army of four legions with cavalry and auxiliaries, about 50,000 in all, to the landing-places of Dover, Hythe, and Richborough.

No mention of London is made in the history of this campaign. Colchester and Gloucester were the principal Roman strongholds.

Writing in the year A.D. 61, Tacitus gives us the first mention of London. He says, “At Suetonius mirâ constantiâ medios inter hostes Londinium perrexit cognomento quidem coloniâ non insigne sed copiâ negotiatorum et commeatuum maxime celebre.”

This is all that we know. There is no mention of London in either of Cæsar’s invasions; none in that of Aulus Plautius. When we do hear of it, the place is full of merchants, and had been so far a centre of trade. The inference would seem to be, not that London was not in existence in the years 55 B.C. or 43 A.D., or that neither Cæsar nor Aulus Plautius heard of it, but simply that they did not see the town and so did not think it of consequence.

If we consider a map showing the original lie of the ground on and about the site of any great city, we shall presently understand not only the reasons why the24 city was founded on that spot, but also how the position of the city has from the beginning exercised a very important influence on its history and its fortunes. Position affects the question of defence or of offence. Position affects the plenty or the scarcity of supplies. The prosperity of the city is hindered or advanced by the presence or the absence of bridges, fords, rivers, seas, mountains, plains, marshes, pastures, or arable fields. Distance from the frontier, the proximity of hostile tribes and powers, climate—a seaport closed with ice for six months in the year is severely handicapped against one that is open all the year—these and many other considerations enter into the question of position. They are elementary, but they are important.

We have already in the first chapter considered this important question under the guidance of Professor T. G. Bonney, F.R.S. Let us sum up the conclusions, and from his facts try to picture the site of London before the city was built.

Here we have before us, first, a city of great antiquity and importance; beside it a smaller city, practically absorbed in the greater, but, as I shall presently prove, the more ancient; thirdly, certain suburbs which in course of time grew up and clustered round the city wall, and are now also practically part of the city; lastly, a collection of villages and hamlets which, by reason of their proximity to the city, have grown into cities which anywhere else would be accounted great, rich, and powerful. The area over which we have to conduct our survey is of irregular shape, its boundaries following those of the electoral districts. It includes Wormwood Scrubbs on the west and Plaistow on the east. It reaches from Hampstead in the north to Penge and Streatham in the south. Roughly speaking, it is an area seventeen miles in breadth from east to west, and eleven from north to south. There runs through it from west to east, dividing the area into two unequal parts, a broad river, pursuing a serpentine course of loops and bends, winding curves and straight reaches; a tidal river which, but for the embankments and wharves which line it on each side, would overflow at every high tide into the streets and lanes abutting on it. Streams run into the river from the north and from the south: these we will treat separately. At present they are, with one or two exceptions, all covered over and hidden.

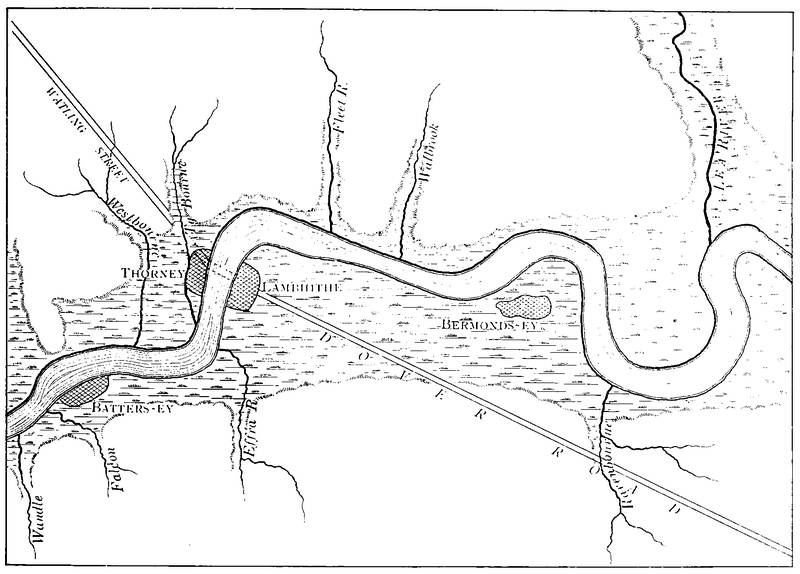

Remove from this area every house, road, bridge, and all cultivated ground, every trace of occupation by man. What do we find? First, a broad marsh. In the marsh there are here and there low-lying islets raised a foot or two above high tide; they are covered with rushes, reeds, brambles, and coarse sedge; some of them are deltas of small affluents caused by the deposit of branches, leaves, and earth brought down by the stream and gradually accumulating till an island has been formed; some are islands formed in the shallows of the river by the same process. These islands are the haunt of innumerable wild birds. The river, which now runs between strong and high embankments, ran through this vast marsh.25 The marsh extended from Fulham at least, to go no farther west, as far as Greenwich, to go no farther east; from west to east it was in some places two miles and a half broad. The map shows that the marsh included those districts which are now called Fulham, West Kensington, Pimlico, Battersea, Kennington, Lambeth, Stockwell, Southwark, Newington, Bermondsey, Rotherhithe, Deptford, Blackwall, Wapping, Poplar, the Isle of Dogs. In other words, the half at least of modern London is built upon this marsh. At high tide the whole of this vast expanse was covered with water, forming exactly such a lovely lake as one may now see, standing at the water-gate of Porchester Castle and looking across the upper stretches of Portsmouth harbour, or as one may see from any point in Poole harbour when the tide is high. It was a lake bright and clear; here and there lay the islets, green in summer, brown in winter; there were wild duck, wild geese, herons, and a thousand other birds flying over it in myriads with never-ending cries. At low tide the marsh was black mud, and on a day cloudy and overcast a dreary and desolate place. How came a city to be founded on a marsh? That we shall presently understand.

Many names still survive to show the presence of the islets I have mentioned.26 For instance, Chelsea is Chesil-ey—the Isle of Shingle (so also Winchelsea). Battersea has been commonly, but I believe erroneously, supposed to be Peter’s Isle; Thorney is the Isle of Bramble; Tothill means the Hill of the Hill; Lambeth is the “place of mud,” though it has been interpreted as the place where lambs play; Bermondsey is the Isle of Bermond. Doubtless there are many others, but their names, if they had names, and their sites have long since been forgotten.

Several streams fell into the river. Those on the north were afterwards called Bridge Creek, the Westbourne, the Tybourne, the Fleet or Wells River, the Walbrook, and the Lea. Those on the south were the Wandle, the Falcon, the Effra, the Ravensbourne, and other brooks without names. Of the northern streams the first and last concern us little. The Bridge Creek rose near Wormwood Scrubbs, and running along the western slope of Notting Hill, fell into the Thames a little higher up than Battersea Bridge. The Westbourne, a larger stream, is remarkable for the fact that it remains in the Serpentine. Four or five rills flowing from Telegraph Hill, at Hampstead, unite, and after running through West Hampstead receive the waters of another stream formed of two or three rills rising at Frognal. The junction is at Kilburn. The stream, thus increased in volume, runs south and enters Kensington Gardens at the head of the Serpentine, into which it flows, passing out at the south end. It crosses Knightsbridge at Albert Gate, passes along Cadogan Place, and finally falls into the Thames at Chelsea Embankment. Of the places which it passed, especially Kilburn Priory, we shall have more to say later on. Meantime we gather that Kilburn, Westbourne Terrace, Knightsbridge, and Westbourne Street, Chelsea, owe their names to this little stream.

The Tyburn, a smaller stream, but not without its importance, took its rise from a spring called the Shepherd’s Well, which formed a small pool in the midst of the fields called variously the Shepherd’s Fields, or the Conduit Fields, but later on the Swiss Cottage Fields. The site is marked by a drinking-fountain on the right hand rather more than half way up FitzJohn’s Avenue. The water was remarkable for its purity, and as late as fifty or sixty years ago water-carts came every morning to carry off a supply for those who would drink no other. The stream ran down the hill a little to the east of FitzJohn’s Avenue, crossed Belsize Lane, flowed south as far as the west end of King Henry’s Road, then turning west, crossed Avenue Road, and flowed south again till it came to Acacia Road. Here it received an affluent from the gardens and fields of Belsize Manor and Park. Thence south again with occasional deflections, east and west, across the north-west corner of Regent’s Park, receiving another little affluent in the Park; then down a part of Upper Baker Street, Gloucester Road, taking a south-easterly course from Dorset Street to Great Marylebone Lane. It crossed Oxford Street at the east corner of James Street, ran along the west side of South Molton Street, turned again to the south-west, crossed Piccadilly at Brick Street, and running across Green Park it27 passed in front of Buckingham Palace. Here the stream entered upon the marsh, which at high tide was covered with water. Then, as sometimes happens with marshes, the stream divided. One—the larger part—ran down College Street into the Thames; the other, not so large, turned to the north-east and presently flowed down Gardener’s Lane and across King’s Street to the river.

The principal interest attaching to this little river is that it actually created the island which we now call Westminster. The island was formed by the detritus of the Tyburn. How many centuries it took to grow one need not stop to inquire: it is enough to mark that Thorney Island, like the Camargue, or the delta of the Nile, was created by the deposit of a stream.

The Fleet River—otherwise called the River of Wells, or Turnmill Brook, or Holebourne—the fourth of the northern streams, was formerly, near its approach to London, a very considerable stream. Its most ancient name was the “Holebourne,” i.e. the stream that flows in a hollow. It was called the River of Wells on account of the great number of wells or springs whose waters it received; and the “Fleet,” because at its mouth it was a “fleet,” or channel covered with shallow water at high tide. The stream was formed by the junction of two main branches, one of which rose in the Vale of Health, Hampstead, and the other in Ken Wood between Hampstead and Highgate. There were several small affluents along the whole course of the stream. The spot where the two branches united was in a place now called Hawley Road, Kentish Town Road. Its course then led past old St. Pancras Church, on the west, between St. Pancras and King’s Cross Stations on the east side of Gray’s Inn Road, down Farringdon Road, Farringdon Street, and New Bridge Street, into the Thames. The wells which gave the stream one of its names were—Clerkenwell, Skinnerswell, Fagswell, Godwell (sometimes incorrectly spelt Todwell), Loderswell, Radwell, Bridewell, St. Chad’s Well. At its mouth the stream was broad enough and deep enough to be navigable for a short distance. It became, however, in later times nothing better than an open pestilential sewer. Attempts were made from time to time to cleanse the stream, but without success. All attempts failed, for the simple reason that Acts of Parliament without an executive police and the goodwill of the people always do fail. Three hundred years later Ben Jonson describes its condition:—

The banks continued to be encumbered with tenements, lay-stalls, and “houses of office,” until the Fire swept all away. After this they were enclosed by a stone28 embankment on either side, and the lower part of the river became a canal forty feet wide, and, at the upper end, five feet deep, with wharves on both sides. Four bridges were built over the canal—viz. at Bridewell, at Fleet Street, at Fleet Lane, and at Holborn. But the canal proved unsuccessful, the stream became choked again and resumed its old function as a sewer. Everybody remembers the Fleet in connection with the Dunciad—

In the year 1737 the canal between Holborn and Fleet Street was covered over, and in 1765 the lower part between Fleet Street and the Thames was also covered.

So much for the history of the stream. Its importance to the city was very great. It formed a natural ditch on the western side. Its eastern bank rose steeply, much more steeply than at present, forming originally a low cliff; its western bank was not so steep. Between what is now Fleet Lane and the Thames there was originally a small marsh covered with water at high tide, part, in fact, of the great Thames marsh; above Fleet Lane the stream became a pleasant country brook meandering among the fields and moors of the north. The Fleet determined the western boundary, and protected the city on that side.

The Walbrook, like the Westbourne, was formed by the confluence of several rills; its two main branches rose respectively in Hoxton and in Moorfields. It entered the city through a culvert a little to the west of Little Bell Alley, London Wall. It ran along the course of that alley; crossed Lothbury exactly east of St. Margaret’s Church; passed under the present Bank of England into Princes Street; and next under what is now the Joint Stock Bank, down St. Mildred’s Court, and so across the Poultry. It did not run down the street called “Walbrook,” but on the west side of it, past two churches which have now vanished—St. Stephen’s, which formerly stood exactly opposite its present site; and St. John, Walbrook, on the north-east corner of Cloak Lane,—and it made its way into the river between the lanes called Friars’ Alley and Joiners’ Hall. The outfall has been changed, and the stream now runs under Walbrook, finding its way into the Thames at Dowgate Dock.

When the City wall was built the water was conducted through it by means of a culvert; when the City ditch was constructed the water ceased, or only flowed after a downfall of heavy rain. But the Walbrook did not altogether cease; it continued as a much smaller stream from a former affluent rising under the south-east angle of the Bank of England. The banks of the Walbrook were a favourite place for the villas of the wealthier people in Roman London; many Roman remains have been found there; and piles of timber have been uncovered. A fragment of a bridge over the stream has also been found, and is in the Guildhall Museum.

It has been generally believed that the Walbrook was at no time other than a very small stream. The following passage, then, by Sir William Tite (Antiquities29 found in the Royal Exchange) will perhaps be received with some surprise. The fact of this unexpected discovery seems to have been neglected or disbelieved, because recent antiquaries make no reference to it. Any statement, however, bearing the name of Sir William Tite deserves at least to be placed on record.

“With respect to the width of the Walbrook, the sewerage excavations in the streets called Tower-Royal and Little St. Thomas Apostle, and also in Cloak Lane, discovered the channel of the river to be 248 feet wide, filled with made-earth and mud, placed in horizontal layers, and containing a quantity of black timber of small scantling. The form of the banks was likewise perfectly to be traced, covered with rank grass and weeds. The digging varied from 18 feet 9 inches in depth, but the bottom of the Walbrook was of course never reached in those parts, as even in Princes Street it is upwards of 30 feet below the present surface. A record cited by Stow proves that this river was crossed by several stone bridges, for which especial keepers were appointed; as also that the parish of St. Stephen-upon-Walbrook ought of right to scour the course of the said brook. That the river was navigable up to the City wall on the north is said to have been confirmed by the finding of a keel and some other parts of a boat, afterwards carried away with the rubbish, in digging the foundations of a house at the south-east corner of Moorgate Street. But whether such a discovery were really made or not, the excavations referred to appear at least to remove all the improbability of the tradition that ‘when the Walbrook did lie open barges were rowed out of the Thames or towed up to Barge yard.’ As the Church of St. Stephen-upon-Walbrook was removed to the present site in the year 1429, it is probable that the river was ‘vaulted over with brick and paved level with the streets and lanes through which it passed’ about the same period; the continual accumulation of mud in the channel, and the value of the space which it occupied, then rapidly increasing, equally contributing to such an improvement.”

Whether Sir William’s inference is correct or no, the river in early times, like the Fleet, partook of the tidal nature of the Thames.

Attempts have been made to prove that a stream or a rivulet at some time flowed along Cheapside and fell into the Walbrook. It is by no means impossible that there were springs in this place, just as there is, or was, a spring under what is now the site of the Bank of England. The argument, or the suggestion, is as follows:—

Under the tower of St. Mary-le-Bow were found the walls and pavement of an ancient Roman building, together with a Roman causeway four feet in thickness. The land on the north side of London was all moorish, with frequent springs and ponds. The causeway may have been conducted over or beside such a moorish piece of ground. Of course, in speaking of Roman London we must put aside altogether West Chepe as a street or as a market. Now it is stated that in the year30 1090, when the roof of Bow Church was blown off by a hurricane, the rafters, which were 26 feet long, penetrated more than 20 feet into the soft soil of Cheapside. The difficulty of believing this statement is very great. For if the soil was so soft it must have been little better than a quagmire, impossible for a foot-passenger to walk upon, and it would have been beyond the power of the time to build upon it. But if the rafters were hurled through the air for 400 feet or so, they might fall into the muddy banks of the Walbrook.14 A strange story is told by Maitland:—

“At Bread Street Corner, the North-east End, in 1595, one Thomas Tomlinson causing in the High Street of Cheap a Vault to be digged and made, there was found, at 15 feet deep, a fair Pavement, like that above Ground. And at the further End, at the Channel, was found a Tree, sawed into five Steps, which was to step over some Brook running out of the West, towards Walbrook. And upon the Edge of the said Brook, as it seemeth, there were found lying along the Bodies of two great Trees, the Ends whereof were then sawed off; and firm Timber, as at the first when they fell: Part of the said Trees remain yet in the Ground undigged. It was all forced Ground, until they went past the Trees aforesaid; which was about seventeen Feet deep, or better. Thus much hath the Ground of this City (in that Place) been raised from the Main.” (Maitland, vol. ii. pp. 826-827.)

It would seem as if at some remote period there had been at this spot either a marsh, or a pond, or a stream. If a stream, when was it diverted, and how? Or when did it dry up, and why? And did the stream, if there was one, run north, west, south, or east? There is no doubt that the ground has been raised some 18 feet since Roman times, for not only were the buildings under Bow Church at that depth, but opposite, under Honey Lane Market, Milk Street, and Mercers’ Hall, Roman remains have been found at the same depth.

In any case, West Chepe could not have come into existence as a market on the site of a running stream or on a quagmire, and the diversion or the digging up of the stream, if there was one, must have taken place before the settlement by the Saxons.

The Lea can hardly be considered as belonging to London. It is within the memory of men still living that suburbs of London have grown up upon its banks. But the marshes which still remain formed anciently an important defence of the City. They were as extensive, and, except in one or two places, without fords. The river which ran through them was broad and deep. It was probably in these marshes that the Roman legions on one occasion fell into difficulties. And except for the fords the Lea remained impassable for a long way north—nearly as far as Ware.

As regards the streams of the south, they have little bearing upon the history of the City. The essential point about the south was the vast extent of the marsh31 spread out before the newly founded town. Until the causeway from Stonegate Lambeth to the rising ground at Deptford was constructed these marshes were absolutely impassable. Four or five streams crossed them. The most westerly of these, the Wandle, discharges its waters opposite to Fulham; it is a considerable stream, and above Wandsworth is still dear to anglers. At its mouth a delta was formed exactly like that at Thorney; this was called afterwards Wandsworth Island. The Falcon Brook ran into the Thames above Battersea; it seems to have been an inconsiderable brook. No antiquary, so far as I know, has ever explored its course. The Effra is an interesting stream, because until quite recently—that is, within the last fifty years—it ran, an open, clear, and very beautiful brook, through the Dulwich Fields and down the Brixton Road past Kennington Church. In Rocque’s map it is made to rise about half a mile west of Dulwich College, near a spot called Island Green, which now appears as Knights’ Hill; but I am informed by a correspondent that this is wrong, and that it really rose in the hills of Norwood. It was a pretty stream flowing in front of cottages to which access was gained by little wooden bridges. The stream was overhung by laburnums, hawthorns, and chestnut trees. I myself remember seeing it as a boy in Dulwich Fields, but it was by that time already arched over lower down. There was a tradition that ships could formerly sail up the Effra as far as Kennington Church. It falls into the Thames nearly opposite Pimlico Pier. Had it kept its course without turning to the west it might have formed part of King Cnut’s trench, which would have accounted for the tradition of the ships. Another and a nameless stream is represented on old maps as flowing through the marsh into the Thames opposite the Isle of Dogs. The most easterly stream is the Ravensbourne, which at its mouth becomes Deptford Creek. This, like the Wandle and the Lea, was higher up a beautiful stream with many smaller affluents.

As for the land north and south of this marsh, it rises out of the marsh as a low cliff from twenty to forty feet high. On the south side this cliff is a mile, two miles, and even three miles from the river. On the north side, while there are very extensive marshes where now are Fulham, South and West Kensington, the Isle of Dogs, and the Valley of the Lea, further eastward the cliff approaches the river, touches it and overhangs it at one point near Dowgate, and runs close beside it as far as Charing Cross, whence it continues in a westerly direction, while the river turns south.

Behind the cliff on the south rose in long lines, one behind the other, a range of gentle hills. They were covered with wood. Between them, on high plateaux, extended heaths of great beauty clothed with gorse, heather and broom, bramble and wild flowers.

On the north the ground also rose beyond the first ridge of cliff, but slowly, till32 it met the range of hills now known as Hampstead and Highgate. All the ground was moorland waste and forest, intersected with rivulets, covered with dark ponds and quagmires: a country dangerous at all times, and sometimes quite impassable. On the northern part was the great forest called afterwards the Middlesex Forest.

Such in prehistoric days was the site of London. A more unpromising place for the situation of a great city can hardly be imagined. Marsh in front, and moor behind; marsh to right, and marsh to left; barren heath on the south to balance waste moorland on the north. A river filled with fish; islets covered with wild birds; a forest containing wild cattle, bear, and wolf; but of arable land, not an acre. A town does not live by hunting; it cannot live upon game alone; and yet on this forbidding spot was London founded; and, in spite of these unpromising conditions, London prospered.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content