Search london history from Roman times to modern day

PLANTAGENET II. PRINCE AND MERCHANT

It is never safe to adopt in blind confidence the conclusions of the antiquary. He works with fragments; here it is a passage in an old deed; here a few lines of poetry; here a broken vase; here the capital of a column; here a drawing, cramped, and out of proportion, and dwarfed, from an illuminated manuscript. This kind of work tends to belittle everything; the splendid city becomes a mean, small town; King Solomon's Temple, glorious and vast, shrinks to the dimensions of a village conventicle; Behemoth himself becomes an alligator; Leviathan, a porpoise; history, read by this reducing lens, becomes a series of patriotic exaggerations. For instance, the late Dr. Brewer, a true antiquary, if ever there was one, could see in medi�val London nothing but a collection of mean and low tenements standing among squalid streets and filthy lanes. That this estimate of the City is wholly incorrect we shall now proceed to show. Any city, ancient or modern, might be described as consisting of mean and squalid houses, because in every city the poor outnumber the rich, and the small{156} houses of the poor are more frequent than the mansions of the wealthy.

When one who wishes to reconstruct a city of the past has obtained from the antiquary all he has discovered, and from the historian all he has to tell, there is yet another field of research open to him before he begins his task. It is the place itself—the terrain—the site of the town, or the modern town upon the site of the old. He must examine that; prowl about it; search into it; consider the neglected corners of it. I will give an example. Fifty years ago a certain learned antiquary and scholar visited the site of an ancient Syrian city, now sadly reduced, and little more than a village. He looked at the place—he did not explore it, he looked at it—he then read whatever history has found to say of it; he proceeded to prove that the place could never have been more than a small and insignificant town composed of huts and inhabited by fishermen. Those who spoke of it as a magnificent city he called enthusiasts or liars. Forty years passed; then another man came; he not only visited the site, but examined it, surveyed it, and explored it. This man discovered{157} that the place had formerly possessed a wall—the remains still existing—two miles and more in length; an acropolis, strong and well situated—the ruins still standing—protecting a noble city with splendid buildings. The antiquary, you see, dealing with little fragments, could not rise above them; his fragments seemed to belong to a whole which was puny and insignificant. This antiquary was Dr. Robinson, and the place was the once famous city of Tiberias, by the shores of the Galilean lake.

In exactly the same manner, he who would understand medi�val London must walk about modern London, but after he has read his historian and his antiquary, not before. Then he will be astonished to find how much is left, in spite of fires, reconstructions and demolitions, to illustrate the past.

Here a quaint little square, accessible only to foot-passengers, shut in, surrounded by merchants' offices, still preserves its ancient form of a court in a suppressed monastery. Since the church is close by, one ought to be able to assign the court to its proper purpose. The hall, the chapter-house, the kitchens and buttery, the abbot's residence, may have been built around this court.

Again, another little square set with trees, like a Place in Toulon or Marseilles, shows the former court of a royal palace. And here a venerable name survives telling what once stood on the site; here a dingy little church-yard marks the former position of a church as ancient as any in the City.

London is full of such survivals, which are known only to one who prowls about its streets, note-book in hand, remembering what he has read. Not one of{158} them can be got from the book antiquary, or from the guide-book. As one after the other is recovered the ancient city grows not only more vivid, but more picturesque and more splendid. London a city of low mean tenements? Dr. Brewer—Dr. Brewer! Why, I see great palaces along the river-bank between the quays and ports and warehouses. In the narrow lanes that rise steeply from the river I see other houses fair and stately, each with its gate-way, its square court, and its noble hall, high roofed, with its oriel-windows and its lantern. Beyond these narrow lanes, north of Watling Street and Budge Row, more of those houses—and still more, till we reach the northern part where the houses are nearly all small, because here the meaner sort and those who carry on the least desirable trades have those dwellings.

You have seen that London was full of rich monasteries, nunneries, colleges, and parish churches, in so much that it might be likened unto the Ile Sonnante of Rabelais. You have now to learn, what I believe no one has ever yet pointed out, that if it could be called a city of churches it was much more a city of palaces. This shall immediately be made clear. There were, in fact, in London itself more palaces than in Verona and Florence and Venice and Genoa all together. There was not, it is true, a line of marble palazzi along the banks of a Grande Canale; there was no Piazza della Signoria, no Piazza della Erbe to show these buildings. They were scattered about all over the City; they were built without regard to general effect and with no idea of decoration or picturesqueness; they lay hidden in narrow winding labyrinthine streets; the warehouses stood beside and between them; the common people dwelt in narrow courts around them; they faced each other on opposite sides of the lanes.

These palaces belonged to the great nobles and were their town houses; they were capacious enough to accommodate the whole of a baron's retinue, consisting sometimes of four, six, or even eight hundred men. Let us remark that the continual presence of these lords and their following did much more for the City than merely to add to its splendor by the erecting of great houses. By their residence they prevented the place from becoming merely a trading centre or an aggregate of merchants; they kept the citizens in touch with the rest of the kingdom; they made the people of London understand that they belonged to the Realm of England. When Warwick, the King-maker,{160} rode through the streets to his town-house, followed by five hundred retainers in his livery; when King Edward the Fourth brought wife and children to the City and left them there under the protection of the Londoners while he rode out to fight for his crown; when a royal tournament was held in Chepe—the Queen and her ladies looking on—then the very school-boys learned and understood that there was{161} more in the world than mere buying and selling, importing and exporting; that everything must not be measured by profit; that they were traders indeed, and yet subjects of an ancient crown; that their own prosperity stood or fell with the well-doing of the country. This it was which made the Londoners ardent politicians from very early times; they knew the party leaders who had lived among them; the City was compelled to take a side, and the citizens quickly perceived that their own side always won—a thing which gratified their pride. In a word, the presence in their midst of king and nobles made them look beyond their walls. London was never a Ghent; nor was it a Venice. It was never London for itself against the world, but always London for England first, and for its own interests next.

Again, the City palaces, the town-houses of the nobles, were at no time, it must be remembered, fortresses. The only fortress of the City was the White Tower. The houses were neither castellated nor fortified nor garrisoned. They were entered by a gate, but there was neither ditch nor portcullis. The gate—only a pair of wooden doors—led into an open court round which the buildings stood. Examples of this way of building may still be seen in London. For instance, Staple Inn, or Barnard's Inn, affords an excellent illustration of a medi�val mansion. There are in each two square courts with a gate-way leading from the road into the Inn. Between the courts is a hall with its kitchen and buttery. Clifford's Inn, Gray's Inn and Old Square, Lincoln's Inn are also good examples. Sion College, before they wickedly destroyed it, showed the hall and the court. Hampton{162} Court is a late example, the position of the Hall having been changed. Gresham House was built about a court. So was the Mansion House. Till a few years ago Northumberland House, at Charing Cross, illustrated the disposition of such mansions. Those who walk down Queen Victoria Street in the City pass on the north side a red brick house standing round three sides of a quadrangle. This is the Herald's College; a few years ago it preserved its fourth side with its gate-way. Four hundred years ago this was the town-house of the Earls of Derby. Restore the front and you have the size of a great noble's town palace, yet not one of the largest. If you wish to understand the disposition of such a building as a{163} nobleman's town-house, compare it with the Quadrangle of Clare, or that of Queens', Cambridge. Derby House was burned down in the Fire, and was rebuilt without its hall, kitchen, and butteries, for which there was no longer any use. As it was before the Fire, a broad and noble arch with a low tower, but showing no appearance of fortification, opened into the square court which was used as an exercising ground for the men at arms. In the rooms around the court was their sleeping accommodation; at the side or opposite the entrance stood the hall where the whole household took meals; opposite to the hall was the kitchen with its butteries; over the butteries was the room called the Solar, where the Earl and Countess slept; beyond the hall was another room called the Lady's Bower, where the ladies could retire from the rough talk of the followers. We have already spoken of this arrangement. The houses beside the river were provided with stairs, at the foot of which was the state barge in which my Lord and my Lady took the air on fine days, and were rowed to and from the Court at Westminster.

There remains nothing of these houses. They are, with one exception, all swept away. Yet the description of one or two, the site of others, and the actual remains of one sufficiently prove their magnificence. Let us take one or two about which something is known. For instance, there is Baynard's Castle, the name of which still survives in that of Baynard's Castle Ward, and in that of a wharf which is still called by the name of the old palace.

Baynard's Castle stood first on the river-bank close to the Fleet Tower and the western extremity of the{164} wall. The great house which afterwards bore this name was on the bank, but a little more to the east. There was no house in the City more interesting than this. Its history extends from the Norman Conquest to the Great Fire—exactly six hundred years; and during the whole of this long period it was a great palace. First it was built by one Baynard, follower of William. It was forfeited in A.D. 1111, and given to Robert Fitzwalter, son of Richard, Earl of Clare, in whose family the office of Castellan and Standard-bearer to the City of London became hereditary. His descendant, Robert, in revenge for private injuries, took part with the Barons against King John, for which the King ordered Baynard's Castle to be destroyed. Fitzwalter, however, becoming reconciled to the King, was permitted to rebuild his house. It was again destroyed, this time by fire, in 1428. It was rebuilt by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, on whose attainder it reverted to the crown. During one of these rebuildings it was somewhat shifted in position. Richard, Duke of York, next had it, and lived here with his following of four hundred gentlemen and men at arms. It was in the hall of Baynard's Castle that Edward IV. assumed the title of king, and summoned the bishops, peers, and judges to meet him{165} in council. Edward gave the house to his mother, and placed in it for safety his wife and children before going out to fight the battle of Barnet. Here Buckingham offered the crown to Richard.

Henry VIII. lived in this palace, which he almost entirely rebuilt. Prince Henry, after his marriage with Catherine of Aragon, was conducted in great{166} state up the river, from Baynard's Castle to Westminster, the Mayor and Commonalty of the City following in their barges. In the time of Edward VI. the Earl of Pembroke, whose wife was sister to Queen Catharine Parr, held great state in this house. Here he proclaimed Queen Mary. When Mary's first Parliament was held, he proceeded to Baynard's Castle, followed by "2000 horsemen in velvet coats with their laces of gold and gold chains, besides sixty gentlemen in blue coats with his badge of the green dragon." This powerful noble lived to entertain Queen Elizabeth at Baynard's Castle with a banquet, followed by fireworks. The last appearance of the place in history is when Charles II. took supper there just before the Fire swept over it and destroyed it.

Another house by the river was that called Cold Harborough, or Cold Inn.

This house stood to the west of the old Swan Stairs. It was built by a rich City merchant, Sir John Poultney, four times Mayor of London. At the end of the fourteenth century it belonged, however, to John Holland, Duke of Exeter, son of Thomas Holland, Duke of Kent, and Joan Plantagenet, the "Fair Maid of Kent." He was half-brother to King Richard II., whom here he entertained. Richard III. gave it to the Heralds for their college. They were turned out, however, by Henry VII., who gave the house to his mother, Margaret, Countess of Richmond. His son gave it to the Earl of Shrewsbury, by whose son it was taken down, one knows not why, and mean tenements erected in its place for the river-side working-men.

Another royal residence was the house called the{169} Erber. This house also has a long history. It is said to have been first built by the Knight Pont de l'Arche, founder of the Priory of St. Mary Overies. Edward III. gave it to Geoffrey le Scrope. It passed from him to John, Lord Neville, of Raby, and so to his son Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmoreland, the stanch supporter of Henry IV. From him the Erber passed into the hands of another branch of the Nevilles, the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick. The King-maker resided here, with a following so numerous that six oxen were daily consumed for breakfast alone, and any person who was allowed within the gates could take away as much meat, sodden and roast, as he could carry upon a long dagger. After his death, George, Duke of Clarence—"false, fleeting, perjured Clarence"—obtained a grant of the house, in right of his wife, Isabel, daughter of Warwick. Richard, Duke of Gloucester, succeeded, and called it the King's Palace during his brief reign. Edward, son of the Duke of Clarence, then obtained it. In the year 1584 the place, which seems to have fallen into decay, was rebuilt by Sir Thomas Pulsdon, Lord Mayor. Its last illustrious occupant, according to Stow, was Sir Francis Drake.

We are fortunate in having left one house at least, or a fragment of one, out of the many London palaces. The Fire of 1666 spared Crosby Place, and though most of the old mansion has been pulled down, there yet remains the Hall, the so-called Throne Room, and the so-called Council Room. The mansion formerly covered the greater part of what is now called Crosby Square. It was built by a simple citizen, a grocer and Lord Mayor, Sir John Crosby, in the fifteenth century; a man of great wealth and great position;{170} a merchant, diplomatist, and ambassador. He rode north to welcome Edward IV. when he landed at Ravenspur; he was sent by the King on a mission to the Duke of Burgundy and to the Duke of Brittany. Shakespeare makes Richard of Gloucester living in this house as early as 1471, four years before the death of Sir John Crosby, a thing not likely. But he was living here at the death of Edward IV., and here he held his lev�es before his usurpation of the crown. In this hall, where now the City clerks snatch a hasty dinner, sat the last and worst of the Plantagenets, thinking of the two boys who stood between him and the crown. Here he received the news of their murder. Here he feasted with his friends. The place is charged with the memory of Richard Plantagenet. Early in the next century another Lord Mayor obtained it, and lent it to the ambassador of the Emperor Maximilian. It passed next into the hands of a third citizen, also Lord Mayor, and was bought in 1516 by Sir Thomas More, who lived here for seven years, and wrote in this house his Utopia and his Life of Richard the Third. His friend, Antonio Bonvici, a merchant of Lucca, next lived in the house. To him More wrote his well-known letter from the Tower. William Roper, More's son-in-law, and William Rustill, his nephew; Sir Thomas d'Arcy; William Bond, Alderman and Sheriff, and merchant adventurer; Sir John Spencer, ancestor of Lord Northampton; Mary, Countess of Pembroke, and sister of Sir Philip Sidney—

the Earl of Northampton, who accompanied Charles I. to Madrid on his romantic journey; Sir Stephen Langham—were successive owners or occupants of this house. It was partly destroyed by fire—not the Great Fire—in the reign of Charles II. The Hall, which escaped, was for seventy years a Presbyterian meeting-house; it then became a packer's warehouse. Sixty years ago it was partly restored, and became a literary institution. It is now a restaurant, gaudy with color and gilding. The Duc de Biron, ambassador from France in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, was lodged here, with four hundred noblemen and gentlemen in his train. And here also was lodged the Duc de Sully.

In a narrow street in the City, called Tower Royal—Tour De La Reole, built by merchants from Bordeaux—survives the name of a house where King{174} Stephen lived in the short intervals when he was not fighting; King Richard II. gave it to his mother, and called it the Queen's Wardrobe; he afterwards assigned it to Leon III., King of Armenia, who had been dispossessed by the Turks. Richard III. gave it to John, Duke of Norfolk, who lived here until his death at the battle of Bosworth Field. There is no description of the house, which must have had a tower of some kind, and there is no record of its demolition: Stow only says that "of late times it has been neglected and turned into stabling for the king's horses, and is now let out to divers men, and is divided into tenements."

The Heralds' College in Queen Victoria Street, already mentioned, stands on the site of Derby House. Here the first Earl, who married the mother of Henry VII., lived. Here the Princess Elizabeth of York was the guest of the Earl during the usurpation of Richard. The house was destroyed in the Fire and rebuilt in a quadrangle, of which the front portion was removed to make room for the new street.

Half a dozen great houses do not make a city of palaces. That is true. Let us find others. Here, then, is a list, by no means exhaustive, drawn up from the pages of Stow. The Fitz Alans, Earls of Arundel, had their town house in Botolph Lane, Billingsgate, down to the end of the sixteenth century. The street is and always has been narrow, and, from its proximity to the fish-market, is and always has been unsavory. The Earls of Northumberland had town houses successively in Crutched Friars, Fenchurch Street, and Aldersgate Street. The Earls of Worcester lived in Worcester Lane, on the river-bank;{177} the Duke of Buckingham on College Hill: observe how the nobles, like the merchants, built their houses in the most busy part of the town. The Beaumonts and the Huntingdons lived beside Paul's Wharf; the Lords of Berkeley had a house near Blackfriars; Doctor's Commons was the town house of the Blounts, Lords Mountjoy. Close to Paul's Wharf stood the mansion once occupied by the widow of Richard, Duke of York, mother of Edward IV., Clarence, and Richard III. Edward the Black Prince lived on Fish Street Hill; the house was afterwards turned into an inn. The De la Poles had a house in Lombard Street. The De Veres, Earls of Oxford, lived first in St. Mary Axe, and afterwards in Oxford Court, St. Swithin's Lane; Cromwell, Earl of Essex, had a house in Throgmorton Street. The Barons Fitzwalter had a house where now stands Grocers' Hall, Poultry. In Aldersgate Street were houses of the Earl of Westmoreland, the Earl of Northumberland, and the Earl of Thanet, Lord Percie, and the Marquis of Dorchester. Suffolk Lane marks the site of the "Manor of the Rose," belonging successively to the Suffolks and the Buckinghams; Lovell's Court, Paternoster Row, marks the site of the Lovells' mansion; between Amen Corner and Ludgate Street stood Abergavenny House, where lived in the reign of Edward II. the Earl of Richmond and Duke of Brittany, grandson of Henry III. Afterwards it became the house of John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, who married Lady Margaret, daughter of Edward III. It passed to the Nevilles, Earls of Abergavenny, and from them to the Stationers' Company. Warwick Lane runs over Warwick House. The Sidneys, Earls of Leicester, lived in the Old Bailey.{178} The Staffords, Dukes of Buckingham, lived in Milk Street.

Such a list, numbering no fewer than thirty-five palaces—which is not exhaustive and does not include the town houses of the Bishops and great Abbots, nor the halls of the companies, many of them very noble, nor the houses used for the business of the City, as Blackwell Hall and Guildhall—is, I think, sufficient{179} to prove my statement that London was a city of palaces.

Nothing, again, has been said about the houses of the rich merchants, some of which were much finer than those of the nobles. Crosby Hall, as has been seen, was built by a merchant. In Basing Lane (now swallowed up by those greedy devourers of old houses, Cannon Street and Queen Victoria Street), stood Gerrard's Hall, with a Norman Crypt and a high-roofed Hall, where once they kept a Maypole and called it Giant Gerrard's staff. This was the hall of the house built by John Gisors, Mayor in the year 1305. The Vintners' Hall stands on the site of a great house built by Sir John Stodie, Mayor in 1357. In the house called the Vintry, Sir Henry Picard, Mayor, once entertained a very noble company indeed. Among them were King Edward III., King John of France, King David of Scotland, the King of Cyprus, and the Black Prince. After the banquet they gambled, the Lord Mayor defending the bank against all comers with dice and hazard. The King of Cyprus lost his money, and, unfortunately, his Royal temper as well. To lose the latter was a common infirmity among the kings of those ages. The Royal Rage of the proverb is one of those subjects which the essayist enters in his notes and never finds the time to treat. Then up spake Sir Henry, with admonition in his voice: Did his Highness of Cyprus really believe that the Lord Mayor, a merchant adventurer of London, whose ships rode at anchor in the Cyprian King's port of Famagusta, should seek to win the money of him or of any other king? "My Lord and King," he said, "be not aggrieved. I court not your gold, but your play; for I{180} have not bidden you hither that you might grieve." And so gave the king his money back. But John, King of France, and David, King of Scotland, and the Black Prince murmured and whispered that it was not fitting for a king to take back money lost at play. And the good old King Edward stroked his gray beard, but refrained from words.

Another entertainer of kings was Whittington. What sayeth the wise man?

"Seest thou a man diligent in his business? He shall stand before kings."

They used to show an old house in Hart Lane,{181} rich with carved wood, as Whittington's, but he must have lived in his own parish of St. Michael's Paternoster Royal, and, one is pretty certain, on the spot where was afterwards built his college, which stood on the north side of the church. Here he entertained Henry of Agincourt and Katherine, his bride, with a magnificence which astonished the king. But Whittington knew what he was doing; the banquet was not ostentation and display; its cost was far more than repaid by the respect for the wealth and power of the city which it nourished and maintained in the kingly mind. The memory of this and other such feasts, we may be very sure, had its after effect even upon those most masterful of sovereigns, Henry VIII. and Queen Bess. On this occasion it was nothing that the tables groaned with good things, and glittered with gold and silver plate; it was nothing that the fires were fed with cedar and perfumed wood. For this princely Mayor fed these fires after dinner with nothing less than the king's bonds to the amount of �60,000. In purchasing power that sum would now be represented by a million and a quarter.

A truly royal gift.

It was not given to many merchants, "sounding always the increase of their winning," thus to thrive and prosper. Most of them lived in more modest dwellings. All of them lived in comparative discomfort, according to modern ideas. When we read of medi�val magnificence we must remember that the standard of what we call comfort was much lower in most respects than at present. In the matter of furniture, for instance, though the house was splendid inside and out with carvings, coats of arms painted and gilt, there{182} were but two or three beds in it, the servants sleeping on the floor; the bedrooms were small and dark; the tables were still laid on trestles, and removed when the meal was finished; there were benches where we have chairs; and for carpet they had rushes or mats of plaited straw; and though the tapestry was costly, the windows were draughty, and the doors ill-fitting. When, with the great commercial advance of the fourteenth century, space by the river became more valuable, the disposition of the Hall, with its little court, became necessarily modified. The house, which was warehouse as well as residence, ran up into several stories high—the earliest maps of London show many such houses beside Queenhithe, and in the busiest and most crowded parts of the City; on every story there was a wide door for the reception of bales and crates; a rope and pulley were fixed to a beam at the highest gable for hoisting and lowering the goods. The front of the house was finely ornamented with carved wood-work. One may still see such houses—streets full of them—in the ancient City of Hildesheim, near Hanover.

On the river-bank, exactly under what is now Cannon Street Railway Station, stood the Steelyard, Guild� Aula Teutonicorum. In appearance it was a house of stone, with a quay towards the river, a square court, a noble Hall, and three arched gates towards Thames Street. This was the house of the Hanseatic League, whose merchants for three hundred years and more enjoyed the monopoly of importing hemp, corn, wax, steel, linen cloths, and, in fact, carried on the whole trade with Germany and the Baltic, so that until the London merchants pushed out their ships{183} into the Mediterranean and the Levant their foreign trade was small, and their power of gaining wealth small in proportion. This strange privilege granted to foreigners grew by degrees. At first, unless the{184} foreign merchants of the Hanse towns and of Flanders and of France had not brought over their wares they could not have sold them, because there were no London merchants to import them. Therefore they came, and they came to stay. They gradually obtained privileges; they were careful to obey the laws, and give no cause for jealousy or offence; and they kept their privileges, living apart in their own college, till Edward VI. at last took them away. In memory of their long residence in the city, the merchants of Hamburg in the reign of Queen Anne presented the church where they had worshipped, All Hallows the Great, with a magnificent screen of carved wood. The church, built by Wren after the Fire, is a square box of no architectural pretensions, but is glorified by this screen.

The great (comparative) wealth of the City is shown by the proportion it was called upon to pay towards the king's loans. In 1397, for instance, London was assessed at �6,666 13s. 4d., while Bristol, which came next, was called upon for �800 only; Norwich for �333, Boston for �300, and Plymouth for no more than �20. And in the graduated poll tax of 1379, the Lord Mayor of London had to pay �4—the same as an Earl, a Bishop, or a mitred Abbot, while the Aldermen were regarded as on the same line with Barons, and paid �2 each.

Between the merchant adventurers, who sometimes entertained kings and had a fleet of ships always on the sea, and the retail trader there was as great a gulf then as at any after-time. Between the retail trader, who was an employer of labor, and the craftsman there was a still greater gulf. The former lived in{185} plenty and in comfort. His house was provided with a spacious hearth, and windows, of which the upper part, at least, was of glass. The latter lived in one of the mean and low tenements, which, according to Dr. Brewer, made up the whole of London. There were a great many of those, because there are always a great many poor in a large town. Nay, there were narrow lanes and filthy courts where there were nothing but one-storied hovels, built of wattle and clay, the roof thatched with reeds, the fire burning in the middle of the room, the occupants sleeping in old Saxon fashion, wrapped in rugs around the central fire. The lanes and courts were narrow and unpaved, and filthy with every kind of refuse. In those crowded and fetid streets the plague broke out, fevers always lingered, the children died of putrid throat, and in these places began the devastating fires that from time to time swept the City.

The main streets of the City were not mean at all; they were broad, well built, picturesque. If here and there a small tenement reared its timbered and plastered front among the tall gables, it added to the beauty of the street; it broke the line. Take Chepe, for instance, the principal seat of retail trade. At the western end stood the Church of St. Michael le Quern where Paternoster Row begins. On the north side were the churches of St. Peter West Chepe, St. Thomas Acon, St. Mary Cole Church, and St. Mildred. On the south side were the churches of St. Mary le Bow and St. Mary Woolchurch. In the streets running north and south rose the spires of twenty other churches. On the west side of St. Mary le Bow stood a long stone gallery, from which the Queen and her{186} ladies could witness the tournaments and the ridings. In the middle was the "Standard," with a conduit of fresh-water; there were two crosses, one being that erected by Edward I., to mark a resting-place of his dead Queen. Round the "Standard" were booths. At the west end of Chepe were selds, which are believed to have been open bazaars for the sale of goods. Another cross stood at the west end, close to St. Michael le Quern. Here executions of citizens were held; on its broad road the knights rode in tilt on great days; the stalls were crowded with those who came to look on and to buy, the street was noisy with the voices of those who displayed their wares and called upon the folk to buy—buy—buy. You may hear the butchers in Clare Market or the costers in Whitecross Street keeping up the custom to the present day. The citizens walked and talked; the Alderman went along in state, accompanied by his officers; they brought out prisoners and put them into the pillory; the church bells clashed, and chimed, and tolled; bright cloth of scarlet hung from the upper windows if it was a feast day, or if the Mayor and Aldermen had a riding; the streets were bright with the colors of that many-colored time, when the men vied with the women in bravery of attire, and when all classes spent upon raiment sums of money, in proportion to the rest of their expenditure, which sober nineteenth-century folk can hardly believe. Chaucer is full of the extravagance in dress. There is the young squire—

Or the carpenter's wife—

Or the wife of Bath, with her scarlet stockings and her fine kerchiefs. And the knights decked their horses as gayly as themselves. And the city notables went clad in gowns of velvet or silk lined with fur; their hats were of velvet with gold lace; their doublets were of rich silk; they carried thick gold chains about their necks, and massive gold rings upon their fingers.

With all this outward show, this magnificence of raiment, these evidences of wealth, would one mark the small tenements which here and there, even in Chepe, stood between the churches and the substantial merchants' houses? We measure the splendors of a city by its best, and not by its worst.

The magnates of London, from generation to generation, showed far more wisdom, tenacity, and clearness of vision than can be found in the annals of Venice, Genoa, or any other medi�val city. Above all things, they maintained the city liberties and the rights obtained from successive kings; yet they were always loyal so long as loyalty was possible; when that was no longer possible, as in the case of Richard II., they threw the whole weight of their wealth and influence into the other side. If fighting was wanted, they were ready to send out their youths to fight—nay, to join the army themselves; witness the story{190} of Sir John Philpot, Mayor in 1378. There was a certain Scottish adventurer named Mercer. This man had gotten together a small fleet of ships, with which he harassed the North Sea and did great havoc among the English merchantmen. Nor could any remonstrance addressed to the Crown effect any redress. What was to be done? Clearly, if trade was to be carried on at all, this enemy must be put down. Therefore, without much ado, the gallant Mayor gathered together at his own expense a company of a thousand stout fellows, put them on board, and sallied forth, himself their admiral, to fight this piratical Scot. He found him, in fact, in Scarborough Bay with his prizes. Sir John fell upon him at once, slew him and most of his men, took all his ships, including the prizes, and returned to the port of London with his spoils, including fifteen Spanish ships which had joined the Scotchman. Next year the king was in want of other help. The arms and armor of a thousand men were in pawn. Sir John took them out. And because the king wanted as many ships as he could get for his expedition into France, Sir John gave him all his own, with Mercer's ships and the Spanish prizes.

To treat adequately of the foreign trade of the city during these centuries would require a volume. It has, in fact, received more than a single volume.[12] The English merchantman sailed everywhere. There were commercial treaties with Brittany, Burgundy, Portugal, Castile, Genoa, and Venice. English merchants who traded with Prussia were empowered by Henry IV. to meet together and elect a governor for the adjustment{191} of quarrels and the reparation of injuries. The same privilege was extended to those who traded with Holland, Zealand, Brabant, Flanders, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. The Hanseatic merchants enjoyed the privileges on the condition—not always obtained—that English merchants should have the same rights as the Hanseatic League. It is easy to understand what commodities were imported from these countries. The trade was carried on under the conditions of continued fighting. First the seas swarmed with Scotch; French and Flemish ships were always on the lookout for English merchant vessels—there was no peace on the water. Then there were English pirates known as rovers of the sea, who sailed about, landing on the coasts, pillaging small towns, and robbing farms. Sandwich was burned, Southampton was burned. London protected herself with booms and chains. The merchant vessels for safety sailed in{192} fleets. Again, it was sometimes dangerous to be resident in a foreign town in time of war; in 1429 Bergen was destroyed by the Danes, and the English merchants were massacred; about the same time English seamen ravaged Ireland and murdered the Royal Bailiff; reprisals and quarrels and claims were constantly going on. Yet trade increased, and wealth with it. Other foreign merchants settled in London besides the Hansards. Florentines came to buy wool, and to lend money, and to sell chains and rings and jewelled work. Genoese came to buy alum and woad and to sell weapons. Venetians came to sell spices, drugs, and fine manufactured things.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century began the first grumblings of the great religious storm that was to burst upon the world a hundred years later. The common sort of Londoners, attached to their Church and to its services, were as yet profoundly orthodox and unquestioning. But it is certain that in the year 1393 the Archbishop of York complained formally to the king of the Mayor, Aldermen, and Sheriffs—Whittington was then one of the Sheriffs—that they were male creduli, that is, of little faith; upholders{193} of Lollards, detractors of religious persons, detainers of tithes, and defrauders of the poor. When persecutions, however, began in earnest, not a single citizen of position was charged with heresy. Probably the Archbishop's charge was based upon some quarrel over tithes and Church dues. At the same time, no one who has read Chaucer can fail to understand that men's minds were made uneasy by the scandals of religion, the contrast between profession and practice. It required no knowledge of theology to remark that the monk who kept the best of horses in his stable and the best of hounds in his kennel, and rode to the chase as gallantly attired as any young knight, was a strange follower of the Benedictine rule. Nor was it necessary to be a divine in order to compare the lives of the Franciscans with their vows. Yet the authority of the Church seemed undiminished, while its wealth, its estates, its rank, and its privileges gave it enormous power. It is not pretended that the merchants of London were desirous of new doctrines, or of any tampering with the mass, or any lowering of sacerdotal pretensions. Yet there can be no doubt that they desired reform in some shape, and it seems as if they saw the best hope of reform in raising the standard of education. Probably the old monastery schools had fallen into decay. We find, for instance, a simultaneous movement in this direction long before Henry VI. began to found and to endow his schools. Whittington bequeathed a sum of money to create a library for the Grey Friars; his close friend and one of his executors, John Carpenter, Rector of St. Mary Magdalen, founded the City of London School, now more flourishing and of greater{194} use than ever; another friend of Whittington, Sir John Nicol, Master of the College of St. Thomas Acon, petitioned the Parliament for leave to establish four schools; Whittington's own company, the Mercers, founded a school—which still exists—upon his death. The merchants rebuilt churches, bought advowsons and gave them to the corporation, founded charities, and left doctrine to scholars. Yet the century which contains such men as Wycliff, Chaucer, Gower, Occleve, William of Wykeham, Fabian, and others, was not altogether one of blind and unquestioning obedience. And it is worthy of remark that the first Master of Whittington's Hospital was that Reginald Pecock who afterwards, as Bishop of Chichester, was charged with Lollardism, and imprisoned for life as a punishment. He was kept in a single closed chamber in Thorney Abbey, Isle of Ely. He was never allowed out of this room; no one was to speak with him except the man who waited upon him; he was to have neither paper, pen, ink, or books, except a Bible, a mass-book, a psalter, and a legendary.

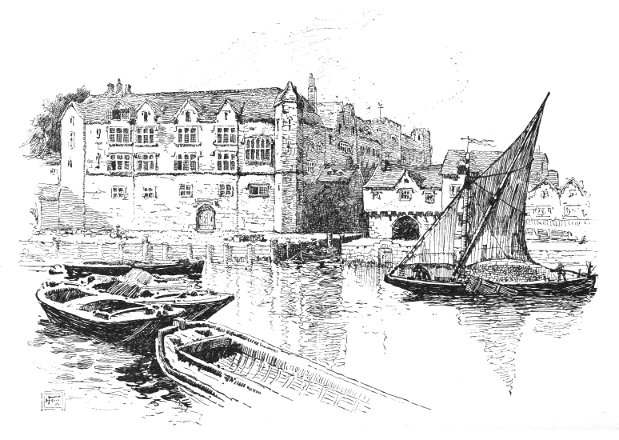

BRIDEWELL PALACE, ABOUT 1660, WITH THE ENTRANCE TO THE FLEET RIVER, PART OF THE BLACK FRIARS, ETC.

BRIDEWELL PALACE, ABOUT 1660, WITH THE ENTRANCE TO THE FLEET RIVER, PART OF THE BLACK FRIARS, ETC.

Among the city worthies of that time may be introduced Sir William Walworth, the slayer of Jack Cade; Sir William Sevenoke, the first known instance of the poor country lad of humble birth working his way to the front; he was also the first to found and endow a grammar-school for his native town; Sir Robert Chichele, whose brother Henry was Archbishop of Canterbury and founder of All Souls', Oxford; this Robert, whose house was on the site of Bakers' Hall in Harp Lane, provided by his will that on his commemoration day two thousand four hundred poor householders of the city should be regaled with a dinner{197} and have twopence in money; Sir John Rainwell, who left houses and lands to discharge the tax called the Fifteenth in three parishes; Sir John Wells, who brought water from Tyburn; and Sir William Estfield, who brought water from Highbury. Other examples show that the time for endowing monasteries had passed away. When William Elsing, early in the fourteenth century, thought of doing something with his money, he did not leave it to the Franciscans for masses, but he endowed a hospital for a hundred blind men; and a few years later John Barnes gave the city a strong box with three locks, containing a thousand marks, which were to be lent to young men beginning business—an excellent gift. When there was a great dearth of grain, it was the Lord Mayor who fitted out ships at his own expense and brought corn from Prussia, which lowered the price of flour by one-half. In the acts of these grave magistrates one can read the deep love they bore to the City, their earnest striving for the administration with justice of just laws, for the maintenance of good work, for the relief of the poor, for the provision of water, and for{198} education. Lollardism was nothing to them. What concerned them in religion was the luxury, the sloth, and the scandalous lives of the religious. Order they loved, because it is only by the maintenance of order that a city can flourish. Honesty in work of all kinds they loved, so that while they hated the man who pretended to do true work and proffered false work, it grieved and shamed them to see one who professed the life of purity wallow in wickedness, like a hog in mud. Obedience they required, because without obedience there is no government. As for the working-man, the producer, the servant, having any share in the profits or any claim to payment beyond his wage, such a thought never entered the head of Whittington or Sevenoke. They were rulers; they were masters; they paid the wage; they laid their hands upon the profits.

Tradition—which is always on the side of the weak—maintains that the great merchants of the past, for the most part, made their way upward from the poorest and most penniless conditions. They came from the plough-tail or from the mechanic's shop; they entered the city paved with gold, friendless, with no more than twopence, if so much, in their pockets; they received scant favor and put up with rough fare. Then tradition makes a jump, and shows them, on the next lifting of the curtain, prosperous, rich, and in great honor. The typical London merchant is Dick Whittington, whose history was blazoned in the cheap books for all to read. One is loath to disturb venerable beliefs, but the facts of history are exactly the opposite. The merchant adventurer, diligent in his business, and therefore rewarded, as the wise man{199} prophesied for him, by standing before princes, though he began life as a prentice, also began it as a gentleman. He belonged, at the outset, to a good family, and had good friends both in the country and the town. Piers Plowman never could and never did rise to great eminence in the city. The exceptions, which are few indeed, prove the rule. Against such a case as Sevenoke, the son of poor parents, who rose to be Lord Mayor, we have a hundred others in which the successful merchant starts with the advantage of gentle birth. Take, for example, the case of Whittington himself.

He was the younger son of a Gloucestershire country gentleman, Sir William Whittington, a knight who was outlawed for some offence. His estate was at a village called Pauntley. In the church may still be seen the shield of Whittington impaling Fitzwarren—Richard's wife was Alice Fitzwarren. His mother belonged to the well-known Devonshire family of Mansell, and was a cousin of the Fitzwarrens. The Whittingtons were thus people of position and consideration, of knightly rank, armigeri, living on their own estates, which were sufficient but not large.

For a younger son in the fourteenth century the choice of a career was limited. He might enter the service of a great lord and follow his fortunes. In that turbulent time there was fighting to be had at home as well as in France, and honor to be acquired, with rank and lands, by those who were fortunate. He might join the livery of the king. He might enter the Church: but youths of gentle blood did not in the fourteenth century flock readily to the Church. He might remain on the family estate and become a{200} bailiff. He might go up to London and become a lawyer. There were none of the modern professions—no engineers, architects, bankers, journalists, painters, novelists, or dramatists; but there was trade.

Young Dick Whittington therefore chose to follow trade; rather that line of life was chosen for him. He was sent to London under charge of carriers, and placed in the house of his cousin, Sir John Fitzwarren, also a gentleman before he was a merchant, as an apprentice. As he married his master's daughter, it is reasonable to suppose that he inherited a business, which he subsequently improved and developed enormously. If we suppose a single man to be the owner of the Cunard Line of steamers, running the cargoes on his own venture and for his own profit, we may understand something of Whittington's position in the city. The story of the cat is persistently attached to his name; it begins immediately after his death; it was figured on the buildings which his executors erected; it formed part of the decorations of the family mansion at Gloucester. It is therefore impossible to avoid the conclusion that he did himself associate the sale of a cat—then a creature of some value and rarity—with the foundation of his fortunes. Here, however, we have only to do with the fact that Whittington was of gentle birth, and that he was apprenticed to a man also of gentle birth.

Here, again, is another proof of my assertion that the London merchant was generally a gentleman. That good old antiquary, Stow, to whom we owe so much, not only gives an account of all the monuments in the city churches, with the inscriptions and verses which were graven upon them, but he also describes{203} the shields of all those who were armigeri—entitled to carry arms. Remember that a shield was not a thing which could in those days be assumed at pleasure. The Heralds made visitations of the counties, and examined into the pretensions of every man who bore a coat of arms. You were either entitled to a coat of arms or you were not. To parade a shield without a proper title was much as if a man should in these days pretend to be an Earl or a Baronet. If one wants a shield it is only necessary now to invent one; or the Heralds' College will with great readiness connect a man with some knightly family and so confer a title: formerly the Herald could only invent or find a coat of arms by order of the Sovereign, the Fountain of Honor. By granting a shield, let us remember, the king admitted another family into the first rank of gentlehood. For instance, when the news of Captain Cook's death reached England, King George III. granted a coat of arms to his family, who were thereby promoted to the first stage of nobility. This, however, seems to have been the last occasion of such a grant.

What do we find, then? This very remarkable fact. The churches are full of monuments to dead citizens who are armigeri. Take two churches at hazard. The first is St. Leonard's, Milk Street. Here were buried, among others, John Johnson, citizen and butcher, died 1282, his coat of arms displayed upon his tomb; also, with his family shield, Richard Ruyener, citizen and fish-monger, died 1361. The second church is St. Peter's, Cornhill. Here the following monuments have their shields: that of Thomas Lorimer, citizen and mercer; of Thomas Born, citizen and{204} draper; of Henry Acle, citizen and grocer; of Henry Palmer, citizen and pannarius; of Henry Aubertner, citizen and tailor; and of Timothy Westrow, citizen and grocer. In short, I do not say that the retail traders were of knightly family, but that the great merchants, the mercers, adventurers, and leaders of the Companies were gentlemen by descent, and admitted to their close society only their own friends, cousins, and sons.

The residence and yearly influx of the Barons and their followers into London not only, as we have seen, kept the city in touch with the country, and prevented it from becoming a mere centre of trade, but it also kept the country in touch with the City. The livery of the great Lords compared their own lot, at best an honorable servitude, with that of the free and independent merchants who had no over-lord but the King, and were themselves as rich as any of the greatest Barons in the country. They saw among them many from their own country, lads whom they remembered in the hunting-field, or playing in the garden before the timbered old house in the country, of gentle birth and breeding; once, like themselves, poor younger sons, now rich and of great respect. When they went home they talked of this, and fired the blood of the boys, so that while some stayed at home and some put on the livery of a Baron, others went up to London and served their time. So that, when we assign a city origin to the families of Coventry, Leigh, Ducie, Pole, Bouverie, Boleyn, Legge, Capel, Osborne, Craven, and Ward, it would be well to inquire, if possible, to what stock belonged the original citizen, the founder of each. Trade in the{205} fourteenth century, and long afterwards, did not degrade a gentleman. That idea was of an earlier and of a later date. It became a law during the last century, when the county families began to grow rich and the value of land increased. It is fast disappearing again, and the city is once more receiving the sons of noble and gentle. The change should be welcomed as helping to destroy the German notions of caste and class and the hereditary superiority of the ennobled House.

As for the political power of London under the Plantagenets, it will be sufficient to refer to Froissart. "The English," says the chronicler, unkindly, "are the worst people in the world, the most obstinate, and the most presumptuous, and of all England the Londoners are the leaders; for, to say the truth, they are very powerful in men and in wealth. In the city and neighborhood there are 25,000 men, completely armed from head to foot, and full 30,000 archers. This is a great force, and they are bold and courageous, and the more blood is spilled the greater is their courage." The deposition of King Edward II. and that of King Richard II. illustrate at once the "presumption and obstinacy" and the power of the citizens. Later on, the depositions of Charles I. and of James II. were also largely assisted by these presumptuous citizens.

The first case, that of Edward II., is thus summed up by Froissart:

When the Londoners perceived King Edward so besotted with the Despencers, they provided a remedy, by sending secretly to Queen Isabella information, that if she would collect a body of 300 armed men, and land with them in England, she would find the citizens of London and the majority of the nobles{206} and commonalty ready to join her and place her on the throne. The Queen found a friend in Sir John of Hainault, Lord of Beaumont and Chimay, and brother to Count William of Hainault, who undertook, through affection and pity, to carry her and her son back to England. He exerted himself so much in her service with knights and squires, that he collected a body of 400 and landed them in England, to the great comfort of the Londoners. The citizens joined them, for, without their assistance, they would never have accomplished the enterprise. King Edward was made prisoner at Bristol, and carried to Berkeley Castle, where he died. His advisers were all put to death with much cruelty, and the same day King Edward III. was crowned King of England in the Palace of Westminster.

When, in the case of Richard II., the time of expostulation had passed, and that for armed resistance or passive submission had arrived, the Londoners remembered their action in the reign of Edward II., and perceived that if they did not move they would be all ruined and destroyed. They therefore resolved upon bringing over from France, Henry, Earl of Derby, and entreated the Archbishop of Canterbury to go over secretly and invite him, promising the whole strength of London for his service. As we know, Henry accepted and came over. On his landing he sent a special messenger to ride post haste to London with the news. The journey was performed in less than twenty-four hours. The Lord Mayor sent the news about in all directions, and the Londoners prepared to give their future king a right joyous welcome. They poured out along the roads to meet him, and all men, women, and children clad in their best clothes. "The Mayor of London rode by the side of the Earl, and said, 'See, my Lord, how much the people are{207} rejoiced at your arrival.' As the Earl advanced, he bowed his head to the right and left, and noticed all comers with kindness.... The whole town was so rejoiced at the Earl's return that every shop was shut and no more work done than if it had been Easter Day."

The army which Henry led to the west was an army of Londoners, twelve thousand strong. It was to the Tower of London that the fallen King was brought; and it was in the Guildhall that the articles drawn up against the King were publicly read; and it was in Cheapside that the four knights, Richard's principal advisers, were beheaded. At the Coronation feast the King sat at the first table, having with him the two archbishops and seventeen bishops. At the second table sat the five great peers of England. At the third were the principal citizens of London; below them sat the knights. The place assigned to the city is significant. But London had not yet done enough for Henry of Lancaster. The Earls of Huntingdon and Salisbury attempted a rebellion against him. Said the Mayor, "Sire, we have made you king, and king you shall be." And King he remained.

It was in this fourteenth century that the city experienced the most important change in the whole history of her constitution, more important than the substitution of the Mayor and Aldermen for the port-reeve and sheriff, though that was nothing less than the passage from the feudal county to the civic community. The new thing was the formation of the city companies, which incorporated each trade formally, and gave the fullest powers to the governing body over wages, hours of labor, output, and everything which concerned the welfare of each craft.{208}

There had been many attempts made at combination. Men at all times have been sensible of the advantages of combining; at all times and in every trade there is the same difficulty, that of persuading everybody to forego an apparent present advantage for a certain benefit in the future; there are always black-legs, yet the cause of combination advances.

The history of the city companies is that of combination so successfully carried out that it became part of the constitution and government of the city; but, which was not foreseen at the outset, combination in the interests of the masters, not of the men.

The trades had long formed associations which they called guilds. These, for some appearance of independence, began to arouse suspicion. Kings have never regarded any combination of their subjects with approbation. The guilds were ostensibly religious; they had each a patron saint—St. Martin, for instance, protected the saddlers; St. Anthony, the grocers—and they held an annual festival on their saint's day. But they must be licensed; eighteen such guilds were fined for establishing themselves without a license. Those which were licensed paid for the privilege. The most important of them was the Guild of Weavers, which was authorized by Henry II. to regulate the trades of cloth-workers, drapers, tailors, and all the various crafts and "mysteries" that belong to clothes. This guild became so powerful that it threatened to rival in authority the governing body. It was therefore suppressed by King John, the different trades afterwards combining separately to form their own companies.

We are not writing a history of London, otherwise{209} the rise and growth of the City companies would form a most interesting chapter. It has been done in a brief and convenient form by Loftie, in his little book on London (Historic Towns Series). Very curious and suggestive reading it is. At the period with which we are now concerned, the end of the fourteenth century, the companies were rapidly forming and presenting regulations for the approval and license of the Mayor and Aldermen. By the year 1363 there were thirty-two companies already formed whose laws and regulations had received the approbation of the King. Let us take those of the Company of Glovers. They are briefly as follows:

(1) None but a freeman of the City shall make or sell gloves.

(2) No glover shall be admitted to the freedom of the City unless with the assent of the Wardens of the trade.

(3) No one shall entice away the servant of another.

(4) If a servant in the trade shall make away with his master's chattels to the value of twelvepence, the Wardens shall make good the loss; and if the servant refuse to be adjudged upon by the Wardens, he shall be taken before the Mayor and Aldermen.

(5) No one shall sell his goods by candlelight.

(6) Any false work found shall be taken before the Mayor and Aldermen by the Wardens.

(7) All things touching the trade within the City between those who are not freemen shall be forfeited.

(8) Journeymen shall be paid their present rate of wages.

(9) Persons who entice away journeymen glovers to{210} make gloves in their own houses shall be brought before the Mayor and Aldermen.

(10) Any one of the trade who refuses to obey these regulations shall be brought before the Mayor and Aldermen.

Observe, upon these laws, first, that the fourth simply transfers the master's right to chastise his servant to the governing body of the company. This seems to put the craftsmen in a better position. Here, apparently, is combination carried to the fullest. All the glovers in the City unite; no one shall make or sell gloves except their own members; the company shall order the rate of wages and the admission of apprentices; no glover shall work for private persons, or for any one, except by order of the company. Here is absolute protection of trade and absolute command of trade. Unfortunately, the Wardens and court were not the craftsmen, but the masters. Therefore the regulations of trade were very quickly found to serve the enrichment of the masters and the repression of the craftsmen. And if the latter formed "covins" or conspiracies for the improvement of wages, they very soon found out that such associations were put down with the firmest hand. To be brought before the Mayor and Aldermen meant, unless submission was made and accepted, expulsion from the City. So long as the conditions of the time allowed, the companies created a Paradise for the master. The workman was suppressed; he could not combine; he could not live except on the terms imposed by his company: if he rebelled he was thrust out of the City gates. The jurisdiction of the City, however, ceased at the walls; when a greater London began to grow{211} outside Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, and Aldgate, and on the reclaimed marshes of Westminster and along the river-bank, craftsmen not of any company could settle down and work as they please. But they had to find a market, which might be impossible except within the City, where they were not admitted. Therefore the companies, as active guardians and jealous promoters of their trades, fulfilled their original purposes a long while, and enabled many generations of masters to grow rich upon the work of their servants.

Every company was governed by its Wardens. The Warden had great powers; he proved the quality, weight, or length of the goods exposed for sale; the members were bound to obey the Warden; to prevent bad blood, every man called upon to serve his time as Warden had to undertake the office. The Warden also looked after the poor of the craft, assisted the old and infirm, the widows and the orphans. He had also to watch over the fraternity, to take care that there should be no underselling, no infringement of the rate of wage, no overreaching of one by the other. He was, in short, to maintain the common interest of the trade. It was a despotism, but, on the whole, a benevolent despotism. The Englishman was not yet ready for popular rule; doubtless the jealousies of the sovereign were allayed by the discovery that the association of a trade was a potent engine for the maintenance of order and the repression of the turbulent craftsman. How turbulent they could be was proved by the troubles which arose in the reign of Henry III.

The great companies were always separate and distinct from the smaller companies. For a long time{212} the Mayor was exclusively elected from the former. Even at the present day, unless the Mayor belongs to one of the great companies, he labors under certain disadvantages. He cannot, for instance, become President of the Irish Society.

By the end of the fourteenth century, then—to sum up—the government of London was practically complete and almost in its present form. The Mayor, become an officer of the highest importance, was elected every year; the Sheriffs every year; the Aldermen and the Common Councilmen were elected by wards. The Mayor was chosen from the great companies, which comprised all the merchant venturers, importers, exporters, men who had correspondence over the seas, masters, and employers. Every craft had its own regulations; no one could trade in the City who did not belong to a company; no one could work in the City, or even make anything to be sold, who did not belong to a company. Wages were ordered by the companies; working-men had no appeal from the ruling of the Warden. From time to time there were attempts made by the craftsmen to make combinations for themselves. These attempts were sternly and swiftly put down. No trades-unions were suffered to be formed; nay, even within the memory of living man trades-unions were treated as illegal associations. The craftsman, as a political factor, disappears from history with the creation of the companies. In earlier times we hear his voice in the folkmote; we see him tossing his cap and shouting for William Longbeard. But when Whittington sits on the Lord Mayor's chair he is silenced. And he remains silent until, by a renewal of those covins and conspiracies{213} which Whittington put down so sternly, he has become a greater power in the land than ever he was before. Even yet, however, and with all the lessons that he has learned, his power of combination is imperfect, his aims are narrow, and his grasp of his own power is feeble and restricted.

For my own part, I confess that this repression, this silencing of the craftsman in the fourteenth century, seems to me to have been necessary for the growth and prosperity of the City. For the craftsman was then incredibly ignorant; he knew nothing except his own craft; as for his country, the conditions of the time, the outer world, he knew nothing at all; he might talk to the sailors who lay about the quays between voyages, but they could tell him nothing that would help him in his trade; he could not read, he could not inquire, because he knew not what question to ask or what information he wanted; he had no principles; he was naturally ready, for his own present advantages, to sacrifice the whole world; he believed all he was told. Had the London working-man acquired such a share in the government of his city as he now has in the government of his country, the result would have been a battle-field of discordant and ever-varying factions, ruled and led each in turn by a short-lived demagogue.

It was, in short, a most happy circumstance for London that the government of the City fell into the hands of an oligarchy, and still more happy that the oligarchs themselves were under the rule of a jealous and a watchful sovereign.

So far it was well. It would have been better had the governing body recognized the law that they{214} must be always enlarging their borders. Then they would have begun in earnest the education of the people. We, who have only taken this work in hand for twenty years, may not throw stones. The voice of the educated craftsman should have been heard long ago. Then we might have been spared many oppressions, many foolish wars, many cruelties. But from the fourteenth to the nineteenth century the craftsman is silent. Nay, in every generation he grows more silent, less able to say what he wants; more inarticulate, more angry and discontented, and more powerless to make his wants heard until he reaches the lowest depth ever arrived at by Englishmen; and that, I think, was about a hundred years ago.

FOOTNOTES

[12] Especially Cunningham's Growth of English Industry and Commerce.

Trying to avoid privacy and cookie settings overwriting content